Title of Work and its Form: “Breatharians,” short story

Author: Callan Wink

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted the October 22, 2012 issue of The New Yorker. At the time of this writing, the story was available in full on the New Yorker web site. “Breatharians” was subsequently selected for The Best American Short Stories 2013.

Bonuses: Here is what Trevor Berrett thought of the story. Here is what Teddy Mitrosilis thought. Consider checking out Mr. Wink’s first collection: Dog Run Moon: Stories.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

August is a young man who is living between two worlds. To paraphrase Britney, he’s not a boy, not yet a man. His mother and father live in separate homes on the same property. His body is strong enough to allow him to kill cats without remorse, but he mourns the loss of his “birth dog.”

The inciting incident of the story is the moment when August’s father tells his son to “get rid of the damn” wild cats in his barn. August is happy to take on the work; he wants pocket money. The story covers the next couple days as the cat slaughter looms in the distance and the reader learns about the protagonist’s situation. It seemed to me as though Mr. Wink was most interested in painting the portrait of his interesting character. There’s an uneasy peace in August’s life: a peace that will be shattered when he finally figures out more about life. Continue Reading

Short Story

Best American 2013, Callan Wink, Narrative Structure, The New Yorker

The British Library did a great service to humanity when they released millions of images from their collections into the public domain. The men and women who created this very, very old printed matter are long dead, but their work lives on. Take a look at this interesting image.

Are your creative juices flowing? This image could inspire so many works of literature:

- A poem about a friend who won’t share his whiskey even if you’re freezing to death.

- A story about two men waiting for their third friend to return so they can head to their cabin.

- A novel about a son coming to grips with a father who never did anything he wanted to do. The son wants to be a ballet dancer…but the father just has to toss some beers into the rowboat and go fishing.

- A video game in which you must resist pushing a button to trigger your friend’s ejector seat, no matter how annoying he gets.

- A story about two friends who are on a trip to fulfill their comrade’s dying wishes by pouring his ashes onto the coast where the three spent so many happy times.

What do you think? What ideas does the image inspire in you?

Uncategorized

GWS Writing Prompt

Friends, Sarah Yaw is a longtime friend of Great Writers Steal. If you haven’t already done so, check out the story of hers that I reprinted. First published in Salt Hill, “Stepping Down” is definitely worth a read. You can also learn a lot about writing from her story.

We are here today, however, to take a look at her excellent first novel, You Are Free to Go, a book that won the 2013 Engine Books Novel Prize. (By all means, purchase a copy from the publishing company itself. Amazon is also happy to sell you a copy.)

I had the pleasure of reading the book before its official release, and I was impressed by the skill with which Ms. Yaw created the world of Hardenberg Correctional Facility and how fully she described the lives of those within its walls. Ms. Yaw also takes the next natural step and communicates the meaning Hardenberg has for those who love its inmates. This “intriguing debut” begins with a close focus on Moses, an appropriately named character who is accustomed to the weariness of his long prison journey. Moses, like most other characters in the book, is shaken when fellow inmate Jorge hangs himself, making permanent the absence felt by his daughter, Gina.

As you can tell from that description, You Are Free to Go has a lot of heavy lifting to do. There are a few complicated settings, including the prison and New York City, and characters who simply can’t and won’t interact with each other. (Corrections officers in federal prisons are pretty firm on that no-one-gets-in-or-out-without-permission thing.) As I thought about what I would say about the book, I kept thinking about how Ms. Yaw balanced the big requirements she had at the beginning of the book. She had to:

- Release a ton of exposition about the prison and the people inside. We need to know all about Jorge in order to feel something upon his death. We must also know about the prison hierarchy and Moses’s ambitions and a good deal about how the prison operates.

- Release a good bit of exposition about Gina and her life in New York City. Gina’s doing very well for herself, though she has plenty to work through. She also has the requisite number of acquaintances, some of whom we must learn about.

- Keep us interested in reading further by ameliorating the affect of her exposition drops through the use of scenework.

It can be very hard to know how much “telling” and how much “showing” we can and must do at the beginning of a work. For example, Jorge is not just going to look at Moses and say, “It’s so great that my daughter went to Brown and has an apartment on the Upper East Side.” No, that’s work for Moses to do in league with the third person narrator.

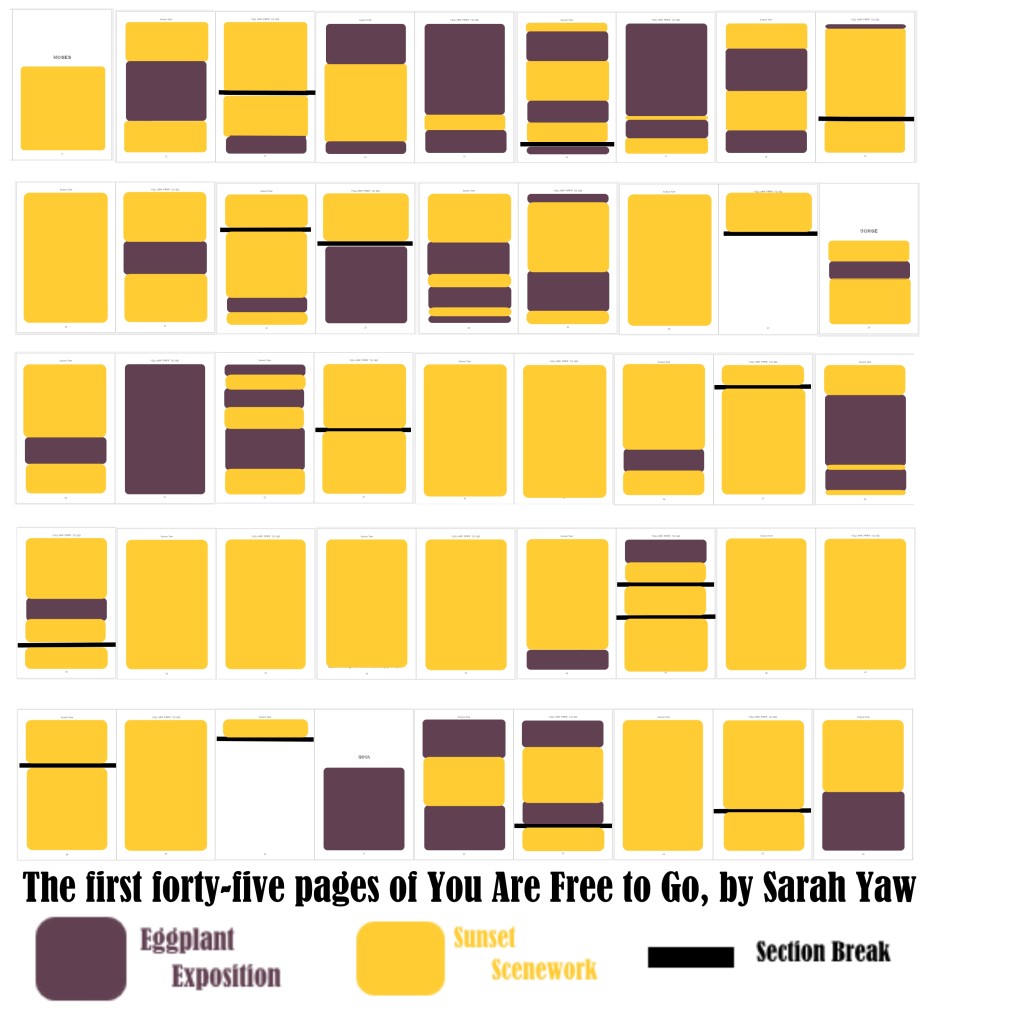

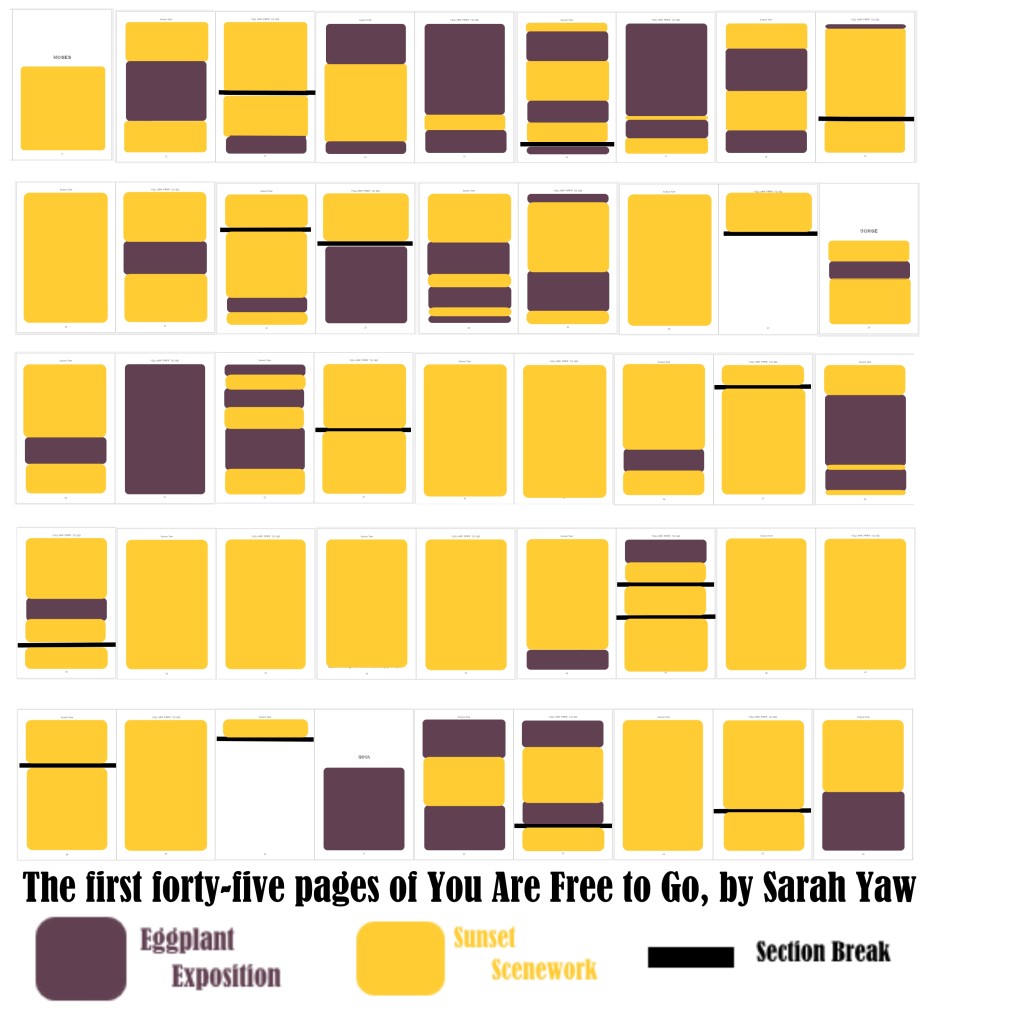

I thought it might be fun to look at the balance between exposition and scene work in a visual manner. In that spirit, I pasted together images of the first 45 pages of You Are Free to Go. The present-tense Scenework is colored in Sunset, and the Exposition is in Eggplant. Take a look:

Isn’t that interesting? Now, there’s always going to be some bleedthrough. Perhaps the narrator released a stray bit of exposition in the middle of a page of dialogue. But what do we notice? How did Ms. Yaw balance the need to tell us things with the need to keep us interested?

- She began the novel in scene. Moses is beginning his day’s work in the mail room. Yes, Ms. Yaw must fill in a lot of information, but instead of TELLING us about Moses, she puts him in contact with Lila and we have some actual drama to care about instead of a great big ball of exposition.

- She drops those big eggplant-colored bombs of exposition (tales from the past, simple explanations) after we already know about Moses and care enough to accept the exposition.

- She makes an interesting turn around page 22. Look how the scenework overwhelms the exposition. One of the scenes is nearly five pages long! All of that is present-tense work that builds the characters and SHOWS us what we need to know about the prison.

- She repeats the formula at the beginning of each chapter. Scenework with a little exposition sprinkled in…then some nice, thick scenes.

I suppose what we can learn from such an exercise is a reinforcement of the oldest writing advice around: show, don’t tell. I guess I sometimes notice a lot of telling in some of the stories I read; perhaps this is why I’ve been wondering if we’re lecturing too much in literary fiction.

The big lesson is to establish your characters as quickly as possible and then let them live their stories.

Here’s an appropriate example. In 1994’s The Shawshank Redemption, writer and director Frank Darabont uses the credit sequence to establish the exposition: ANDY DUFRESNE WAS FALSELY CONVICTED OF KILLING HIS WIFE AND HER LOVER. HE IS GOING TO SHAWSHANK.

With that exposition out of the way, Darabont introduces the other characters: Red, Warden Norton, Byron Hadley, Brooks Hatlen. Darabont is successful enough in his showing, not telling that we care very deeply about what would otherwise be an incredibly boring scene. No one wants to watch prisoners tar the roof of a building for four minutes. But everyone wants to watch Andy Dufresne regain some of his dignity and earn the respect of the others on the tarring crew, some of whom didn’t particularly like him. (There’s an added bonus in that Andy’s facility with numbers springboards the plot.)

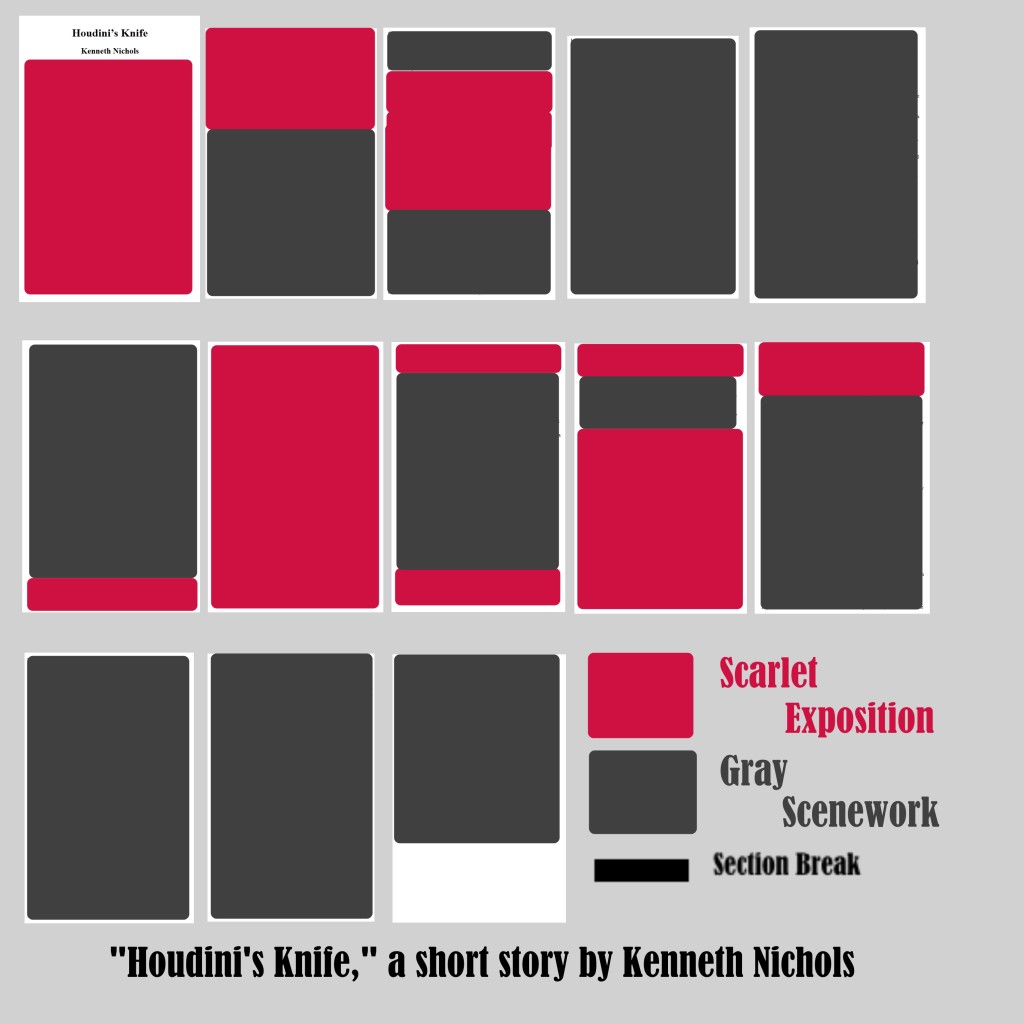

After turning the opening of Ms. Yaw’s novel into an art project, I started to wonder what would happen if I did the same thing to one of my own stories. What would the balance look like?

“Houdini’s Knife” is one of the debut titles from Great Writers Steal Press, and I actually think it’s pretty good. (I usually hate my work.) I’m publishing work that I believe will appeal to a wider audience than most literary stuff. (You Are Free to Go is another example; I can picture my father enjoying the book.) Wouldn’t it be nice if we could break out of the writers-writing-for-other-writers doldrums and reclaim the proverbial “woman on the bus?”

You’ll forgive me for offering you a link to the Great Writers Steal Press website: readingisnothomework.wordpress.com/ See? We need to convince more non-writers that reading is not homework.

You may also enjoy the way I’m experimenting with how we market short stories. See what I did for “Houdini’s Knife?” Maybe you pick up a copy. Why not?

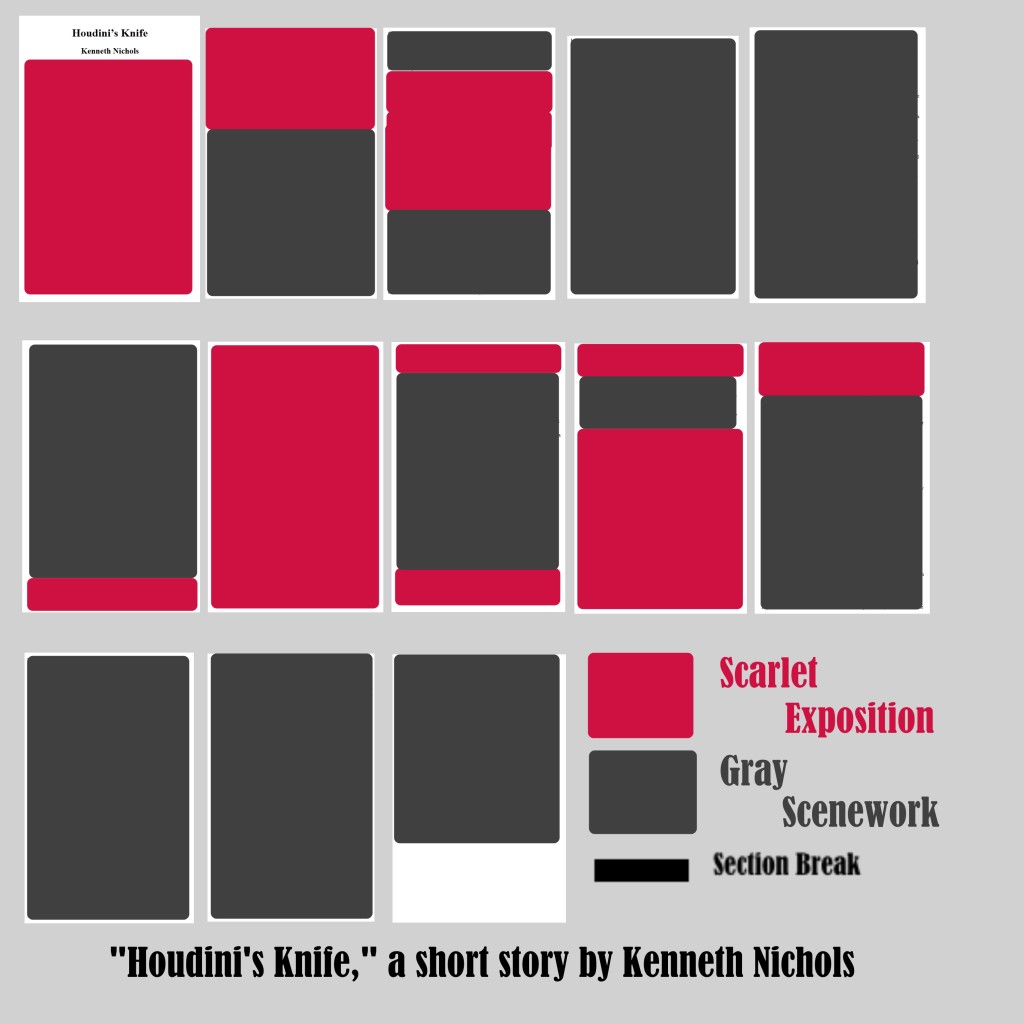

Back to analysis. I gave my story the same treatment as I did You Are Free to Go. In case you didn’t know, I’m a Buckeye. The exposition is in scarlet and the scenework is in gray.

Now, “Houdini’s Knife” was consciously composed as a kind of biography of an eighteen-year-old guy. (I deliberately omitted section breaks in an attempt to keep momentum flowing in the narrative.) The story begins with exposition; I had to reveal that Raymond’s father was a mason. The father died. Raymond was adopted. Raymond got into magic. Raymond has a crush on Becky Brennan. But look!

I did the same thing Ms. Yaw did! I had to tell you a lot about Raymond and his circumstances before I could describe Raymond doing magic tricks. You have to care about Raymond before you care about his chat with Becky Brennan. And once all of that boring exposition is out of the way, I can hit you with the appropriate and compelling ending. (Don’t worry; I don’t usually feel good about anything I write.)

What happens if you give your stories the same treatment? What are some interesting outliers that violate this structure, but are still incredibly compelling? Most of all, isn’t it interesting to think of narrative in a different way?

Reminder: You Are Free to Go is available in all fine independent bookstores, from Barnes and Noble, from Amazon and from Engine Books. You can find more about Sarah Yaw at her website and can say hello to her on Twitter.

Novel

Houdini's Knife, Sarah Yaw, You Are Free to Go

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Caille Millner is a columnist and editorial writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. In those pursuits, Ms. Millner has a responsibility to the truth. Thankfully, she also enjoys the occasional adventure on the fiction side of the tracks. One of these is “The Surrogate,” a story that appeared in Joyland Magazine.

Ms. Millner is available on Twitter. Once you are done reading her story and the reasoning behind some of her choices, why not send her 140 characters about how much you liked her story?

1) The inciting incident is super clear in the story. Franco says he wants to have a “baby of his own” with Cecily. The confession changes the story, just like a good inciting incident should. But then you go several pages without addressing Franco’s request again; you spend a lot of time telling us about their marriage and how Cecily’s surrogacy works.

How do you think you maintained tension in the narrative while putting the main conflict aside for a little while?

The work of surrogacy is naturally tense, just by the simple facts of how it works. A woman who needs money performs the labor of pregnancy for someone else, according to someone else’s rules and standards — and she often has to do so while caring for her own children and her own family.

That’s a situation fraught with all kinds of emotions. Yet we’ve mostly chosen to keep all of these details under wraps. Think of how many times you’ve read in a newspaper that someone wealthy gave birth “via surrogate,” as if the surrogate were a machine instead of a human being.

They aren’t machines, they’re women, and there’s usually a stark class divide between the surrogates and their clients. The U.S. is one of the only developed countries that allows paid surrogacy — most of the others feel like the attendant ethical questions are too much for them to handle, as a society. We don’t even talk about the ethical questions.

But that silence makes the situation rich ground for storytelling and exploration. Simply unrolling the details of Cecily’s situation creates a feeling of tension in the reader, because when as you slowly let the details sink in, you realize that everything about Cecily’s situation is emotionally extreme.

2) At least a few of the sentences in your story are what I call “backwards sentences.” For example:

“It’s the closeness of the way that they have to live that makes her uneasy.”

“To cool the house they’ve got all the lights off;…”

How come you put the subject of the sentence (or clause) so far in?

The narrative POV in this story wasn’t too far away from the subjects, so I occasionally wrote the narration in a way that they might speak themselves. It keeps up the rhythm of their voices.

3) This happens about 60% of the way through the story:

“He smiles and gets up to go into the black maw of the kitchen, bringing back a beer for himself and a diet soda for her. She isn’t supposed to drink the diet sodas but she does anyway.”

What’s this choice all about? I guess I understand that Cecily has decided to take mild risks by drinking caffeine during pregnancy. But why did you make Franco bring her the diet soda?

It’s a small gesture that seemed natural to their relationship. And it’s in keeping with their personalities. Franco is a decent, considerate man who would like to do more for everyone than he’s currently capable of doing. Cecily is sitting down, outwardly passive, but in reality doing far more work than other people feel comfortable enough to acknowledge.

4) About halfway through, the narrator’s mind-reading powers shift from focusing on Cecily to focusing on Franco. I know you had to do that because Franco and Omar had to do some stuff together in the story without Cecily there.

What made the POV switch in the story okay?

Because it’s a story about their relationship, and about how this massive, bizarre situation that they’re in has affected their ability to connect and to give to each other. There are two people in that equation, and the readers needed to hear from the other one.

5) Last lines are always really important! Here’s yours:”Cecily has to nearly choke before she realizes that she’s been holding her breath while she watches.”

Those words stick out for me: “has to nearly choke.” The rest of the sentence flows, but “has to nearly choke” feels to me like the kind of speed bump that means something. What was your thinking there?

I’m glad you caught that! I wanted to give the reader a physical sensation very close to the one she was experiencing in that moment. If you say the sentence aloud, you’ll notice that running all of the syllables together is difficult, the sequence of words deliberately slows you down. It’s a way to collect all of the unspoken tension and emotion so that you can feel it again before you leave this family.

Caille Millner is a writer, essayist, and memoirist. She’s the author of The Golden Road: Notes on my Gentrification (Penguin Press), an editorial writer and weekly columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, and has had essays in The Los Angeles Review of Books and A New Literary History of America. Her awards include the Barnes and Noble Emerging Writers Award and the undergraduate Rona Jaffe award for fiction.

Short Story

Caille Millner, Joyland Magazine, Why'd You Do That?

It’s Labor Day as I write this. As any writer can attest, there really is no day off. We’re always thinking about the next story, the next poem. We’re always asking our characters what they should do next or just living with a problem in our heads, hoping a solution makes itself apparent.

The overwhelming majority of writers have “real” jobs, too. Did you read my recent cry from the heart? I’m trying to help writers help themselves by expanding the tent and inviting in the readers of “literary” fiction that we’ve alienated over the past few decades with our increasing insularity and rejection of entertainment as a priority in literary work.

Did you see Matthew Gannon and Wilson Taylor’s 2013 piece for Jacobin that was recently picked up by Salon? The authors provide us with an excellent history of Labor Day and engage in a powerful analysis of the work of a writer who is indeed a working-class hero: Kurt Vonnegut. Gannon and Taylor are indeed inspiring:

Literature is not – and cannot – be the only force in this fight for economic justice, but its potential contributions should not be understated. Vonnegut is such a potent example of this literary-labor nexus because of his immense popularity. Readers treasured Vonnegut’s literary imagination not just for his stance on politics and economics, but his masterful storytelling, his inimitable wit, and his humanistic compassion. Binding these literary qualities together with his political outlook makes him relevant more than ever today.

I’m beyond depressed to report that the authors are forgetting one crucial oversight. Yes, Vonnegut is one of the titans of twentieth-century American literature. His books exemplify my personal aesthetic (and that of Great Writers Steal Press) because they are entertaining and meaningful, in that order. While eleventh-grade English teachers have been assigning Vonnegut for decades, reading the man is not homework. He shares new ideas and plays with language and appeals to the child and adult inside us all at the same time.

I’m sure it’s fair to say that many non-writers are reading Vonnegut because of sheer cultural momentum, but he surely holds a smaller share of the proverbial “men and women on the bus” than he did in the sixties or seventies. There are fantastic “literary writers” today who address labor issues and the like in an interesting and accessible fashion-T.C. Boyle comes to mind.

The great problem is that literature can not have a powerful effect on a populace when few are reading it. Tattoo this backwards on your forehead so you don’t forget:

We have lost a significant of those people we are hoping to entertain and motivate. We need to get them back by emphasizing Vonnegut and those like him who are still alive.

Ask yourself some very important questions:

Were Today’s Vonnegut twenty-three years old right now, would his early work get him into an MFA program?

Would Today’s Vonnegut receive equal respect from science fiction readers and literary readers?

Would Today’s Vonnegut be able to get a teaching position, an agent or a book contract for his books, ones that seldom feature the voices of women or people of color and surely would catch the ire of cultural pedants for “retrograde” social attitudes?

If Slaughterhouse-Five were released today, would it make a sound?

Gannon and Taylor’s piece is very well-written and I liked it a great deal, but this essay of my own is an attempt to take their discussion one step further: how do literary readers reclaim the blue-collar reader so we can have some of the same cultural effect Vonnegut did in decades past?

I don’t have all the answers, but I do know that we’ll never solve the problem if we don’t acknowledge it exists.

I am certainly no Kurt Vonnegut and neither is my pal Curtis Bradley Vickers. We are both united, however, in our desire to bring literary work back to the masses. Consider visiting readingisnothomework.wordpress.com and letting us know if we’re on the right track. Pick up one of our eBooks. Stories cost one-third as much as a cup of coffee. My chapbook still costs less than a large iced coffee at Dunkin’ Donuts. (And it will stay with you longer.)

Uncategorized

Great Writers Steal Press, Kurt Vonnegut