Friends, after writing my piece about her story “Magic Man,” Sheila Kohler was kind enough to bring her novel Dreaming for Freud to my attention. (Do I wish I already knew about every cool book out there? Yes. Is it possible to read or even to know about every great novel out there? Sigh…no.)

Great Writers Steal readers (and anyone interested in writing craft) would do well to take a look at her book. Why? Because Ms. Kohler is a good writer and an interesting human being. Sure. Why else? Because she has “stolen” in the most magnificent manner, in a way that we should emulate.

Dreaming for Freud is a fictional retelling of a real-life story, that of “Dora,” one of Sigmund Freud’s patients. (Ms. Kohler has an advanced degree in psychology in addition to all of her other accomplishments…go ahead. Be healthily jealous.) The case itself looks very interesting and has a lot of significance in the field of psychology. Dr. Freud-get this-talked to Dora about her life and used his experience with other patients to figure out the specific problems that were holding Dora from happiness.

Freud wrote up his observations and described the treatment he provided in a case study that subsequently became a controversial milestone in the field of psychology. I’m having trouble finding a public domain copy of Freud’s writings about Dora in English; it looks like the English translations were completed decades after Sigmund put dip pen to paper. I did, however, find what seems to be Dora’s diary. Is your German better than mine? Check out “Bruchstück einer Hysterie-Analyse” as Freud intended.

Ms. Kohler used the real-life story as her starting point for Dreaming for Freud; Dora and her relatives are all characters in the book, breathed to life by the author’s muse. Although based on the factual case study, Dora and Herr und Frau Z. are rendered in fiction.

Why is the book’s conceit so cool and such a good idea on Ms. Kohler’s part?

- The story itself has a lot of inherent natural conflict. A young woman in turmoil. A world-famous figure treats her. The suggestion of something…interesting happening between a man and his wife.

- You know…it can sometimes be hard to come up with stories. This one is offered to all of us on a silver platter. (Though you should wait a while to write about Dora; Ms. Kohler just did it.)

- Sigmund Freud has a lot of name recognition. Readers are often willing to give a story a chance if they have an entry point.

- It can be a LOT of fun to work with real-life characters or situations that already appeal to us. Each of us has our special, personal interests that we would like to share with others; writing this kind of work allows us to play in a favorite sandbox.

Have other writers fictionalized real-life stories? Oh yeah. Here’s Two of Us, a film whose writer decided to tell the story of a day in the life of Lennon and McCartney as they hung out several years after the breakup of The Beatles:

Did John really say all of those things to Paul? Probably not. Did you realize that the actor portraying John Lennon is the same guy who played Lane Pryce in Mad Men? Probably not. (It’s weird; I don’t know why.) As writers of fiction, it’s our job to spin reality out of fiction…people like Ms. Kohler simply start out with a little more “fact” in the hopper than J.K. Rowling when she wrote her Harry Potter books.

Here’s another example: As the Allies spent the Spring of 1945 closing in on Berlin, the evil Josef Mengele and other high-ranking Nazis did indeed find their way to South America. Decades later, rock star Nazi hunters such as Simon Wiesenthal did indeed dedicate their lives to finding these war criminals. Ira Levin used these real-life truths as a springboard for his novel The Boys From Brazil. (Thankfully, we have no reason to believe that Hitler was cloned.)

Lauren Weisberger was a personal assistant to a big-time fashion magazine editor. She used these true experiences as the basis for The Devil Wears Prada.

The Bell Jar is, more or less, the autobiography of Sylvia Plath’s young adulthood.

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is the somewhat true story of Hunter S. Thompson traveling to Las Vegas.

You’re under no obligation, of course, to fictionalize your own story. Ms. Kohler adapted a case study. You can do the same. Here are some examples from the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science. “Stealing” from case studies-provided you don’t violate anyone’s privacy, of course-is great because the mere existence of a case study means that a real human being has a problem. The person in question has family and friends who care…there’s tension everywhere!

I happen to have read a few case studies recently; the psychologist’s prose also makes them great seeds for writers. When composing his or her document, the mental health professional is doing what they can to write very clearly for colleagues. You’ll get the basics: the protagonist’s age, family relations, relevant childhood traumas, problematic behaviors and the probable causes for those behaviors. You’ll also read about the protagonist’s treatment and whether or not it worked. You have the right (and perhaps the obligation) to use those basics as you will.

I am also reminded of another favorite story repository: court decisions. I know…I know…these are all boring legal documents. Except they’re not. Plessy and Ferguson were not just names you had to learn in middle school. They were real people who had a great story! So the decision didn’t exactly go the right way for Fred Korematsu, but his honest-to-goodness struggle is a story waiting to be stolen and fictionalized. (Why not put a manque of Mr. Korematsu in a work of science fiction? Sadly, there will always be a “next” Korematsu v. United States, even if there are different names involved.) A few months ago, I happened to pluck a law book off of a shelf in the library and read a harrowing story. I only recall the broad strokes. The case was deciding who was at fault for the death of a child. It was something like 1919 in New York City. The utility company turned on the gas in an apartment at a time the landlord wasn’t expecting, so the landlord hadn’t make sure the gas pipes were plugged. The new renter entered his apartment with his son, struck a match so he could see around him and…well, you can figure it out. (Interestingly, this was in the days before natural gas was spiked with mercaptan, the chemical that now gives it that tell-tale rotten egg smell.

See how many captivating stories are out there waiting to be stolen? Why not pick up a copy of Dreaming for Freud? And maybe discuss the novel with your book group? And then pilfer a story of your own?

Novel

2014, Penguin, Sheila Kohler, Sometimes a Cigar is Just a Cigar

Dear reader, teaching is often as frustrated as it is rewarding. A teacher cannot force students to care or to learn or to grow…that desire must come from within. Well, Peter Melnick is a former student of mine, and a fascinating young man who has that internal desire. The gentleman was kind enough to think of me in the rush of excitement he felt after a brush with his writing idol. I suggested that he might want to share his thoughts and inspiration with all of you by writing an essay about the experience. It is just our luck; he agreed to write an essay for all of us and Great Writers Steal is quite pleased to present it. Mr. Melnick also happens to be a graphic designer and has been kind enough to produce an attractive PDF of the piece that you can read and download.

The Tough Shit I Learned from Kevin Smith

Peter Melnick

I’m pretty sure that if I never discovered the work of Kevin Smith, I would not have taken the path I had in life to become an artist as both a writer and graphic designer.

Bold statement, isn’t it? While that may be the case, it is most certainly true. Back in 2001, Jay & Silent Bob Strike Back hit the theaters. Around the time this movie was coming out, I was a 12 year old about to enter the 7th grade. Unfortunately due to having a parent who didn’t want to take me to an R-rated film (understandable), I wouldn’t be able to see the film until a few months later on VHS. Before that would happen, I was able to get my hands on a copy of the film’s script and somehow convinced my 7th grade “Reading” teacher to let me take the script and do a book report on it. My school had both an English teacher for that grade and a “Reading” teacher – the difference between the two classes? I couldn’t tell you even if I tried. Thankfully the script was released as a physical book from Miramax and I didn’t have to take 90 something pieces of stapled printer paper and use that. I probably got a good grade on it. It’s been almost 13 years since I was in middle school, so I couldn’t tell you every single grade I got back then. All I know is that not long after reading the script and then watching the movie, that exposure made me into a fan of Kevin and his work.

When you’re a kid and you discover things like films, television shows, etc., you sort of become obsessed. Deny it all you want, but it’s true. When I was 5 years old, I was completely obsessed with the Power Rangers. Three years later? Star Wars was the love of my life. A year later? Pokemon. I think you get the point. Once you discover something you like, you want to do whatever you can to learn more and enjoy what you love. Discovering the work of Kevin Smith was no different. Once I finally saw Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, I had to see everything he had committed to celluloid. By the time I reached 8th grade, I practically wore out my VHS copies of the Clerks animated series and Mallrats.

Fast forward to Fall 2007. My grades were in the toilet from high school, but I decided to enroll at my local community college to try and boost them. Sitting in the registrar’s office, I wasn’t sure exactly what I wanted to do. I didn’t want to choose Liberal Arts as a major mainly due to the fact that math and I are just not compatible. So right then and there while looking at the options I had available, I decided to go with Graphic Design as a major. Now what does this have to do with Kevin Smith? Numerous times throughout his career, he has told people to “do what you enjoy,” so I did just that. I had really enjoyed working with Photoshop over the years prior, so I thought why not?

Now we move ahead two years and I graduated from that community college with an Associates Degree in Graphic Design. At this time, I had gotten accepted by SUNY Oneonta, but due to circumstances beyond my control, I was not able to attend. For the next year, I decided to continue my education (i.e. avoid the real world for another year) and go into Communications since there were no other programs that interested me quite like that one. Again, I went with Kevin’s logic of “do what you enjoy.”

During this time, I was reapplying to some of the schools to which I applied to a year earlier. One of the schools that caught my eye was SUNY Oswego. My best friend had been attending for the past year and told me how great it was, so I decided to go for it. During that first semester, I took two Creative Writing courses, one with Leigh Wilson and the other with Chris Motto. Both were phenomenal professors and made me realize that writing was something else that I enjoyed on top of my work in Graphic Design.

The next semester rolled around and I was in a meeting with my advisor. During said meeting, she made the suggestion that perhaps I could add a minor to my college career. Looking through my options, I decided that maybe Creative Writing was the right thing for me. Over the years of watching Kevin’s work, I realized that what he was doing was essentially getting out how he felt about the world around him, expressed his thoughts through written word. This led to myself taking a poetry class the year prior at my previous college. Much like Kevin, I was writing out how I felt about the world around me. Though these were short bursts of expression, I knew that if I could bring out those thoughts in small doses, I could certainly do it in larger ones as well.

As the semester was ending, it was time to start scheduling what was to come in the Fall. The thing that I was gung ho on was taking a screen writing course. Unfortunately, I was not able to get into any of the classes. Instead, I decided to go another route: playwriting. Since both were similar in many ways (and different in others, obviously), I decided to go that route. As luck would have it, an introductory course on the subject was open for the Fall semester and was being taught by Kenneth Nichols. The only downside to the class was the 8 AM start time. Regardless, I went in and I appreciated what was being taught to me. Nichols’s teaching method was unique in that he didn’t rely strictly on showing the standard playwriting materials like the work of the greats in the field, but rather often presented clips from sitcoms, films, and even news programs. By using these sources, he showed us ways to borrow methods from other forms of media and incorporate it into our playwriting. Additionally, he showed us that it doesn’t matter where inspiration comes from. As long as something connects with you, you’ll be set. Kevin would even go on to do something similar when he worked on his soon-to-be released film, Tusk. He found a bizarre ad online and creativity was brought forth.

It wasn’t until a full year later that I would be able to take the followup course. When I did, I fell further in love with the concept of playwriting. One of the most important things that Brad Korbesmeyer gave us was the ability to have our plays read aloud and even acted out in class. Doing so, we were able to see just how things work and how they don’t. It’s one thing to think over the lines in your head, but it’s another to actually see the words and actions on your page come to life. When a play is going into production, you can’t really fix things up during a live reading. The people who are putting on the production usually like the play the way it is and may not want to see changes. With Brad’s method of having the class act out the play, you still have time for revisions for your upcoming drafts. On top of all of that, you can also get to cringe when one of your lines doesn’t sound the way you want it to (though that’s not really a positive thing to experience).

After graduating college and leaving Oswego, I returned home. One of the very first things I did was start writing again. The problem with leaving school, however, is you don’t really have deadlines. Instead, you have to create your own and go from there. Without official deadlines, sometimes it will become “oh, I’ll write tomorrow” or “I’ll write after the weekend is over.” For myself, this would go from days of not writing to weeks and finally, to months.

Over the course of the past year and a half, I have run into different people who occupy prominent places in a wide range of creative realms. Quite a few of them would be comic book writers due to my love of the medium. In many ways, the job of a comic book writer can be hard since they’re constantly on the spot to create original content on a monthly basis. Since they have such a heavy burden with issues (no pun intended) like that, I felt it would be good to get advice from them. I would hear from people like Evan Dorkin (of Milk and Cheese and Beasts of Burden fame), Justin Jordan (writer of The Strange Talent of Luther Strode), and Jill Thompson (of Scary Godmother fame). On top of all of this, I was able to hear from Bryan Johnson (the writer/director of the film Vulgar) who gave me the simple, yet valuable advice of “write every day.”

One bit of advice would come almost a year after my graduation from college. Who was it from you ask? Writer/director/producer/actor/podcaster/Bane vocal impersonator, Kevin Smith. Early in the month of May, it was announced that Kevin would be doing an “AMA” (Ask Me Anything) on the website Reddit. I knew immediately I had to ask him a question. Unfortunately, due to the large number of users, it would be impossible to get him to see my question in time, so I decided to write up my question in detail ahead of time. After all, if I’m going to ask the man something, I might as well go all the way. Ten minutes before the official thread was posted, I copied my message/question to Kevin into my phone. I then proceeded to continually refresh the app I was using like a person anxiously waiting to enter a store on Black Friday to see when the AMA was posted so I could post my question.

About 5-6 minutes before the AMA was supposed to start, I noticed that Kevin had just posted the official thread. As fast as I could, I opened up the discussion and posted my question into the box and submitted it. My question was one of the first two or three submitted, so I know that he had at least seen it. I then went over to his profile and kept refreshing to see how many answers he had given. The first one was a humorous one in which he answered back to someone who asked if they could his accountant. After that, there would not be another answer from Kevin from another several minutes. In the meantime, I noticed that my comment was getting buried at the bottom of the page with “downvotes” (Downvotes are a way to hide posts on Reddit you may not agree with or find acceptable. In this case, people were downvoting my question so their’s could be seen by Kevin over mine.), to the point that it was in the negative numbers.

This was my message that I relayed to Kevin:

“Hi Kev,

First off, I want you to know that I absolutely adore your work. It was your work that pushed me in the direction of wanting to become a writer in the first place (even going as far as adding on a Creative Writing minor to my college degree in Graphic Design). Your ability to manipulate language and so forth really inspired me and for that, I thank you. Yes, it’s cliche to say, but you are my hero.

Now, over the past few months, I’ve been doing some writing and trying to keep at it daily. There have been a number of times where I don’t know what to do next. I stare at the screen and try to figure out what to write. Others would say it’s “writer’s block,” but I’m one of those who believes such a thing does not exist.

Prior to the recent work that I’ve been doing, I would stop writing for days to even weeks. Lately though, I’ve been of the mindset where I have to push myself to write even if I don’t think it’s very good.

So, what I want to know is what keeps you going? What inspires you to write and have there been times where even you, a man who is verbally gifted didn’t know what to put to paper/type on a keyboard?”

Then it happened.

I refreshed my phone and saw the following reply to my question:

“Honestly? Death motivates me. One day it all ends for our hero, and he doesn’t get to express myself anymore. Nightmare thought for a motor mouth full of ideas (some of which are actually good). What am I waiting for? Might as well spit it all out now while I’ve got the chance.

You know what also helps? Change up the creative outlet from time to time. A writer writes, sure - but a writer can also podcast, and sometimes saying shit out loud can help. Or go take some photographs. Or shoot a short film. Or paint. Even if the words aren’t flowing, capture SOME moment that you can share or convey to others: that’s your only job as an artist. Don’t worry about whether it’s ‘good’ or ‘bad’, as art is in the eye of the beholder anyway. You just capture the moment, by any means necessary (Except, y’know, any way that hurts or kills someone else).”

After briefly shaking from the realization that the guy who made me want to become a writer actually acknowledged me, I began to calm down and to absorb the wisdom he had granted me. The idea that life ends really didn’t occur to me when it comes to writing. My lack of foresight was due, in part, to being young and believing in the “tomorrow will be another day” mentality. With that bit of advice from Kevin, it made me realize I should let whatever thoughts flow into whatever it is that I’m writing as there may not be a second, third, fourth, or even fifth chance. When the opportunity arises, you should grab it and write. Literally, if you want to take writing seriously, you should do it as though your life depends on it. Otherwise, those thoughts will never be free and be shared with the world around you. In a way, I wish I knew that bit of advice sooner for the fact that maybe I could have gotten more things out earlier than I did. To be fair, however, there’s no time like the present, so it shouldn’t matter how soon or how late I began writing. The fact I’m getting all of my thoughts out now is the most important thing.

The suggestion of taking part in as many activities as possible was also incredibly helpful. Like I had stated earlier, I’m a graphic designer and writer. I already have my hands in two pots. Why not go and do more? Be creative in as many avenues as possible. Sure, the product of one might not be as good as the others, but it doesn’t matter. You’re capturing how YOU feel. It shouldn’t matter what the quality is. Look at the work of Ed Wood. Sure, what he made wasn’t great to many, but he gave the world his vision (no matter how strange it was). There were probably some better takes from his films that made it to the cutting room floor, but what he used was what he felt was right for that situation.

Will I listen to every bit of advice that Kevin gave me? Absolutely. In many ways, it helped push me to go further as a writer. I shouldn’t look back and I shouldn’t be so critical of my own work. I’m also going to be starting up a blog of my own in the near future to jot down my thoughts about the world around me. I used to maintain a blog when I was a teenager, but eventually abandoned it. The blog isn’t the only place where my writing abilities will be showcased. For the past few months, I’ve been keeping busy working on a play that I hope to shop around to various playwriting contests within the next few months. I’m always going to be a graphic designer, first and foremost. I preoccupy my time doing freelance work for clients in a variety of realms, be it logo design, poster work, among others.

I just feel that no matter what, if you want to be serious about what you do, you should live every day like it could be your last. Be brave and take a chance. This can be in the form of the littlest things like starting a blog or painting a picture, to the large like going skydiving or bungee jumping. Kevin told me to “capture the moment” and I hope to do so not just with my art, but also with my life.

Peter Melnick is a graphic designer, writer, and graduate of the State University at Oswego. If you would like to take a glimpse into his everyday life, follow him on Twitter (http://www.twitter.com/PeterMelnick). He is not related to the composer of the same name, but was once friends with said composer on Facebook for a day.

Creative Nonfiction, Feature Film

2014, 37, Chewlies Gum, Clerks, Finger Cuffs, GWS Essay, I'm Not Even Supposed to Be Here Today, Kevin Smith

Title of Work and its Form: “Magic Man,” short story

Author: Sheila Kohler (on Twitter @sheilakohler)

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the April 2012 issue of Yale Review. Elizabeth Strout and Heidi Pitlor subsequently chose the piece for Best American Short Stories 2013.

Bonuses: Here is the New York Times review of Becoming Jane Eyre, Ms. Kohler’s 2009 novel. Ms. Kohler writes a column for Psychology Today. You can find her essays here. Here is what Karen Carlson thought of “Magic Man.”

Want to see Sheila Kohler and Edmund White discuss fiction? Say, “Thanks The Center For Fiction!”

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Classic Forms

Discussion:

The story is not very long, but it is powerful. Sandra and her children live in Europe, but they are on vacation in South Africa. She has three daughters; S.P. is the oldest, but Jessamyn, the youngest, is Sandra’s favorite. Ms. Kohler releases the story in an interesting fashion. While the whole story is told in the third person, each section alternates between a third person narrator limited first to Sandra’s perspective and then to S.P.’s. Sadly, the story is a kind of cautionary fairy tale. Eight-year-old S.P. wanders off for a bathroom break and some alone time. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work out that way. (I’m being vague because you should just read the darn story!)

Ms. Kohler notes that the story was inspired by “Der Erlkönig,” a poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and the folk tales that inspired it. It just so happens that I have a history with that poem. In fact, it’s one of the few that I have committed to memory. (That list is pretty much limited to “Der Erlkönig,” “To Be or Not to Be” and “Two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles onions on a sesame seed bun.”) Frau Coulter (rest in peace!) had us memorize the poem in first-year German. She was right; my interactions with German have all related to “Der Erlkönig” in some way.

Goethe composed the poem in 1782 and Franz Schubert famously used the text in one of his lieder. Many a young person has sung this song in school voice lessons and competitions.

Frau Coulter led us in numerous group readings of each stanza and tested us on solo recitations. I guess “Der Erlkönig” was primarily a homework assignment at the time, but I loved pronouncing the strange words that were made up of such exotic sounds. I loved the rhyme and the meter. And I loved the story. The poem begins “in medias res:”

Wer reitet so spät durch Nacht und Wind?

Es ist der Vater mit seinem Kind;

Er hat den Knaben wohl in dem Arm,

Er faßt ihn sicher, er hält ihn warm.

What does that all mean? Goethe’s work is in the public domain. Many translations are not. I therefore present my terrible, awful translation of the first stanza:

Who is that riding through the inclement weather so late at night?

It is the father with his child.

He has the little boy wrapped safely in his arm,

He holds the boy tightly, he keeps the boy warm.

The existential threat is out there in Goethe’s work, nipping at the heels of father and son. The same is true in “Magic Man.” Little S.P. tells her siblings stories about this supernatural, fantastic creature, a man who can turn you into a toad if he likes. (Perhaps a reference to Der Froschkönig?) S.P. is being pursued as much as the boy in “Der Erlkönig” was. We meet the “magic man” through her perspective; he’s as charming and persuasive as the titular villain of Goethe’s poem. The Magic Man tempts S.P. with the prospect of playing with his lonely son, just as Der Erlkönig tempts the boy with his daughters:

“Willst, feiner Knabe, du mit mir gehn?

Meine Töchter sollen dich warten schön;

Meine Töchter führen den nächtlichen Reihn,

Und wiegen und tanzen und singen dich ein.”

My terrible translation that is so bad that it’s better termed an “approximation:”

Will you come with me, you fine little boy?

My daughters will take care of you.

My daughters lead the dances at night,

And they will cradle, dance and sing with you.

In “Magic Man,” Ms. Kohler appropriates the form of the fairy tale. See how close “Magic Man” is to a Grimm Brothers story? To a Hans Christian Andersen story? (And to “Der Erlkönig”?) Now, the Magic Man is the only “conceivably supernatural” element of the piece, but many other fairy tale conventions are present:

- A child who is old enough to be a little independent

- That child leaves the safety of parents/home

- The child goes on a journey through nature all alone

- The child encounters some kind of danger while on his or her own

- The antagonist demands something of great value from the protagonist

What’s the overall lesson here? “Steal” these classic forms and bring them into the current day. Where would you put a contemporary Hansel and Gretel? I’ve always wanted to write some story inspired by “Unter der linden.” (Although I’m guessing it would be more of a romance. One hopes.) The specifics of any form may change, I suppose, but many thematic concepts will remain constant. Think about horror movies; the big baddies change depending on society’s great fears at the time.

Most of the story is told in the present tense. This is a wonderful choice for the kind of story that Ms. Kohler is telling; it’s a young girl going out into the woods to meet a kind of monster. Ms. Kohler ends the story with an interesting move, violating the structure she established. In the last section told from the third person narrator limited to Sandra’s perspective, Ms. Kohler makes a leap from the present to the future simple tense:

Years later, she will remember that moment of rage…and she will feel the rage again…she will feel…

Ordinarily, switching tense or perspective is a mistake. It’s up to the writer to make the switch “okay.” Ms. Kohler makes the POV switching okay by adding white space between sections, thereby informing the reader of what she’s doing. I like Ms. Kohler’s tense change because it comes near the end of the story and it doesn’t contain a great deal of action. It makes sense because the emotion of “rage” certainly fits with the emotion the reader has when thinking about S.P.’s situation at the time. Perhaps most importantly from a writing perspective, this tense change makes the next one okay.

The last paragraph, according to the rules Ms. Kohler established, is told from Sandra’s perspective:

Years later, when her sister is dead, killed by her husband driving the car off the road, her child will tell her the whole story…

Now THAT is much more of a quantum leap than the last tense shift, right? Stuff happened! The characters do more than just feel emotions. Ms. Kohler prepared us for this leap, making it feel perfectly natural.

Tense and time shifts are perfectly valid storytelling techniques; they just need to be employed properly. Think of one of the finest films in cinema history:

Demolition Man begins as John Spartan is trying to rescue hostages that are being held by Simon Phoenix. Spartan fails and he is blamed for the dead civilians. Both Spartan and Phoenix are cryogenically frozen for their crimes. The narrative of the film simply jumps ahead 36 years. Are we mad? Nope. The director gives us a million clues to let us know that things have changed. (Just as Ms. Kohler eased us into the possibility that she would zip into the future in the last paragraph.)

What Should We Steal?

- Create modern examples of classic forms. Contemporary folks may be a little less likely to believe in witches, but we’ll always have equivalent figures.

- Prepare your reader for the judicious changes in tense and time frame that you make. Your narrator can take us anywhere and anytime…so long as your changes make sense.

Short Story

Best American 2013, Classic Forms, Sheila Kohler, Yale Review

Starting a story can be very difficult, but it’s equally important to craft an opening passage that captures your reader’s attention and gets the narrative humming along. In this video, I examine how some of the authors whose stories are immortalized in The Best American Short Stories 2012 fulfilled their responsibilities in their opening sentences.

Video

2014, Best American 2012, GWS Video, Kate Walbert, Mike Meginnis, Roxane Gay, Steven Millhauser, T.C. Boyle

My plan for total domination of all media is taking FOREVER. I am making strides, however, by making more videos.

The MFA debate has been raging for a very long time. Should you get one? Should you not? Well, those Okla Elliott offered an interesting new take on the discussion that I thought merited an audio/video discussion:

Video

2014, As It Ought to Be, GWS Video, Okla Elliott

Title of Work and its Form: “Malaria,” short story

Author: Michael Byers (on Twitter @The MichaelByers)

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the Fall 2012 issue of Bellevue Literary Review. The kind folks at the journal have made the story available online. “Malaria” was subsequently selected for Best American Short Stories 2013 and is included in the anthology.

Bonuses: Here is an interview Mr. Byers gave to Hot Metal Bridge. Here is where you can find the books Mr. Byers has published. (In addition to works published by people who have similar names.) Here is what Karen Carlson thought of the story. Here is the book trailer for Percival’s Planet:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Opening Passages

Discussion:

Several years ago, Orlando was in the blush of first love with a woman named Nora. But this is not a love story. Instead, Orlando is working out his understanding of George, Nora’s brother. George is an adult, but has some mental health concerns. The man was getting by, but had a bit of an incident that exacerbated Nora’s worries about herself and her future.

Yes, I’m being a bit vague in the summary. Why? Mr. Byers has given us a story that is not about a bang-bang narrative. Instead, the gentleman seems to want to explore the effect of mental health issues on the people who love the afflicted. Mr. Byers makes the very wise choice of keeping the story comparatively short; the slack narrative feels just fine in a story of this length.

The first thing I would like to point out is the skillful way in which Mr. Byers begins his story. Unfortunately, I read this piece just a little too late to include it in my video about the topic.

Let’s look at the first two sentences:

When I was in college in Eugene I had a girlfriend named Nora Vardon. We had fallen together sort of accidentally, I talked to her first at a vending machine where we were both buying coffee, and things progressed in the usual slow ways, we went out one cold night to look at the blurry stars, and that led to some kissing, and from there we started the customary excavation of our families, revealing, not quite competitively, how crazy they both were, she with a raft of depressives and schizophrenics and me with a bunch of drunks, mainly the men on my father’s side.

What has Mr. Byers packed into the opening passage?

- POV. We know it’s a first person story.

- Time frame. We know that the story took place some time ago, when the narrator “was in college.” The narrator also describes the love affair with the kind of wistful regret that is only granted with distance and earned wisdom.

- Diction. Mr. Byers gives us a beautiful second sentence that is enjoyable on its own.

- Subject matter. Romance takes a backseat to the real theme, which relates to mental illness.

- Internal narrative logic. Mr. Byers begins at the beginning of Orlando’s relationship with the Vardons, the central conflict/issue in the story.

Take a look at the first few sentences of one of your own stories. Are you packing in as much as Mr. Byers does?

A line or two later, Mr. Byers did something that seemed quite significant to me. (Your mileage may vary, of course.) I loved the sad suggestion of the tense Mr. Byers used in this sentence:

She had an open, genial, feline face, with big cheeks and dark eyes, and a big soft body that was round in parts…

Nora “had” an open face. We’ve only just begun our journey with Orlando, but that “had” is extremely suggestive. What is going on with Nora now? Is she okay? Are they just not together? Did they have a meaningful relationship? We may not have these questions had Mr. Byers cast the sentence differently:

- My old girlfriend had…

- Nora, my college girlfriend…

- I loved her open, genial, feline face…

- Nora, bless her heart, was a beautiful woman with a…

Instead, Mr. Byers has Orlando tell us that Nora “had” that face. (“Gee…I hope nothing happened to it.”) I guess I’m urging us to think deeply about how we use tense in our work. Think back to your first real breakup. The one that wrenched your heart and made you wear all black to school the next day. What should you say if you’re trying to convince others that the long-ago heartbreak isn’t a problem for you now?

- Sally broke up with me before graduation. (past simple)

- Sally was breaking up with me before graduation. (past continuous)

- Sally had broken up with me before graduation. (past perfect)

- Sally had been breaking up with me before graduation. (past perfect continuous)

Each sentence means pretty much the same thing, but the tense employed in the sentences carries a different meaning.

What Should We Steal?

- Pack your opening passage full of everything your reader needs to understand your story. The longer you take to introduce important elements, the greater the chance you lose your reader.

- Choose the tense that carries the subtextual meaning appropriate to your work. “The divorce meant nothing to Sally” or “The divorce HAD meant nothing to Sally”?

Short Story

2012, Bellevue Literary Review, Best American 2013, Michael Byers, Opening Passages

Title of Work and its Form: “Directions: Exit This Burning Building,” poem

Author: Alexis Pope (on Twitter @alexisflannery)

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem debuted in Issue 17 of Coconut Magazine. You can read the work here. The poem was subsequently reprinted in Bone Matter, the Lettered Streets Press chapbook that Ms. Pope shared with Aubrey Hirsch.

Bonuses: Here is an interview Ms. Pope granted to Vouched Books. Here is a poem Ms. Pope placed in Guernica. I’ve said it a thousand times: poetry is usually best when heard rather than read. Here’s a video of Ms. Pope reading some of her work:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Lineation

Discussion:

Well, the meaning of a published poem is determined by the reader, not the poet. I don’t know if Ms. Pope had this in mind, but it seemed to me that “Directions” is a three-section poem about a lover warning another that their relationship may not be a lifetime of wine and roses. Each section features a potent image described in slightly abstract band that keeps the meaning open to interpretation.

One of the reasons I liked this poem is because of the way Ms. Pope plays with the lines. The work in the chapbook is helpful to me (as it may be to you) because Ms. Pope is far more “experimental” than I tend to be. It’s wonderful, isn’t it? If you’re a more “conventional” poet, you can enjoy Ms. Pope’s poem and try to understand how they work in the interest of improving your own work!

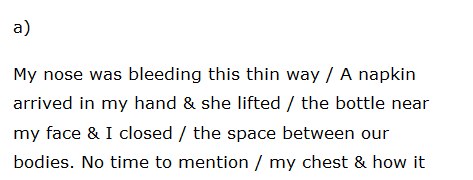

Here’s a section of Ms. Pope’s first stanza. (Yes, I was careful to ensure the lineation is the same as in her chapbook; these things can change a little depending on the size of your browser window.)

In the chapbook, the right margins are justified, too. (Darn digital world…) You’ll notice immediately that Ms. Pope has inserted a slash into each of her lines. In case you weren’t aware, a slash is the way you signify a line break in a poem when you can’t reproduce the lines as intended. For example, here’s the first stanza of “Annabel Lee” as it might be quoted under circumstances in which a writer couldn’t reproduce the author’s original lines:

It was many and many a year ago, /In a kingdom by the sea, /That a maiden there lived whom you may know /By the name of Annabel Lee; /And this maiden she lived with no other thought /Than to love and be loved by me.

Ms. Pope could just have hit “return” when she wanted a new line. What does Ms. Pope gain by placing a slash in each of her lines?

- The poem (to my mind) is about the restrictions that we place on ourselves and others in a relationship. Doesn’t a slash make perfect visual sense. That slash is a real barrier to reflect the emotional barrier that may be present.

- The slashes muddy the poem somewhat, allowing (or forcing us) to understand the lines in different ways. Which do we prefer as the first line? “My nose was bleeding this thin way” or “My nose was bleeding this thin way / A napkin arrived in”? Ms. Pope clearly wants to force her reader into a more analytical state of mind.

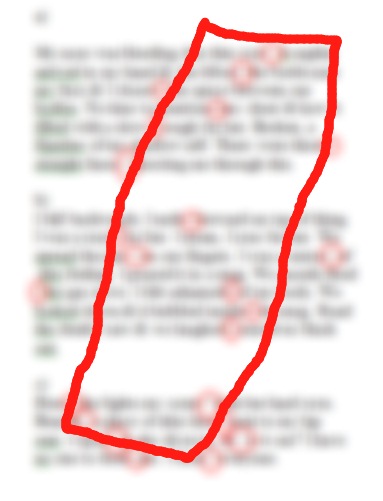

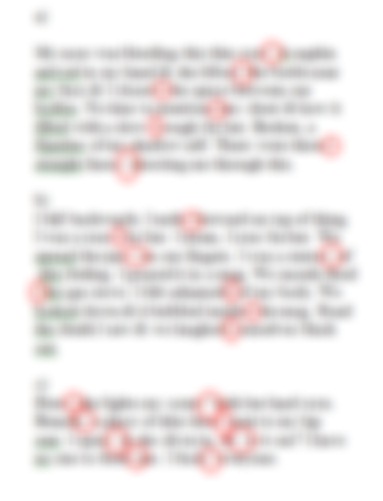

Here’s number 3 and possibly the most fun thing that Ms. Pope gains with her structure. Take a look at the poem with all of the slashes circled in red:

I blurred the words because I wouldn’t dream of reprinting Ms. Pope’s poem without permission. Further, the shape of the slashes take on a form when you’re not thinking of the words, don’t they?

I blurred the words because I wouldn’t dream of reprinting Ms. Pope’s poem without permission. Further, the shape of the slashes take on a form when you’re not thinking of the words, don’t they?

No, the correlation isn’t perfect, of course. But can you allow your pareidolia go to work? The many slashes in the poem create blank spaces that attract your eyes. The poem seems to contain a slash, doesn’t it?

No, the correlation isn’t perfect, of course. But can you allow your pareidolia go to work? The many slashes in the poem create blank spaces that attract your eyes. The poem seems to contain a slash, doesn’t it?

The form of the poem reflects the subject matter, facilitated at least in part because of the way that Ms. Pope uses the slashes in the lines.

The form of the poem reflects the subject matter, facilitated at least in part because of the way that Ms. Pope uses the slashes in the lines.

What Should We Steal?

- Consider the internal structure of your lines in addition to the way they affect the whole. A poem may benefit if the reader is invited to play with and rearrange the lines on their own.

- Allow the form of your work to reflect its specific elements and its theme. A poem that is (to me) about resisting some facets of a romantic relationship can contain slashes…and can also suggest one.

Poem

2013, Alexis Pope, Aubrey Hirsch, Coconut Magazine, Lineation

Title of Work and its Form: Adam Carolla and The Adam Carolla Show and his multiple best-selling books and successful television shows…and everything else.

Author: Adam Carolla (on Twitter @adamcarolla)

Where the Work Can Be Found: Mr. Carolla’s many ventures can be found all over the place. His program Catch a Contractor can be found on Spike TV. His books are published by HarperCollins. His podcast network, Carolla Digital, produces a number of great shows, including Penn’s Sunday School and This Week with Larry Miller.

Bonuses: Here is Mr. Carolla’s discussion with Artie Lange:

Here is an episode The Adam & Drew Show that begins with a fascinating monologue from Mr. Carolla:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Having a Motor and Getting it On

Discussion:

I am well aware that Mr. Carolla may not be everyone’s cup of tea. But that’s okay. I am extremely grateful to live in a country in which the solution to rhetoric that we don’t like is simply more rhetoric. And Mr. Carolla knows a thing or two about rhetoric. His books hit the bestseller lists. His Spike TV show is doing very well. His podcast network churns out a couple dozen hours of free entertainment every week. Even though Mr. Carolla will be the first to admit that he’s written more books than he’s read, the gentleman can teach us a great deal about building an audience and keeping them coming back for more.

I’ve been listening to Mr. Carolla’s podcast for a few years, and he always comes back to a few critical philosophies to which we should all adhere.

Here’s what we should steal from Adam Carolla:

- Have a motor - Mr. Carolla points out that successful people tend to do a lot of things and are often itching to move onto their next projects. We all went to high school with people who did NOT have a motor…those folks may not be doing very well at the moment. In general, the people who were always doing SOMETHING ended up succeeding.

- Give away 80% of your time and effort to make money with the other 20%. Mr. Carolla gives away his podcasts for free. Sure, he has advertisers, but I’m guessing that he makes most of his money through his other ventures. He created his own brand of alcoholic beverage called “Mangria.” He travels the country doing live shows. He does TV shows and pilots. Appearing on late-night shows and Dancing With the Stars doesn’t pay much, but these efforts give Mr. Carolla the audience he needs in order to make monty the other ways.

- Offer your reader bang for their buck. Mr. Carolla complains about it-complaining about everything is one of his funniest bits-but the gentleman goes the extra mile in treating his fans well and giving them extra time and energy. He signs Mangria bottles and books after his shows. He takes pictures with people even though he hates the passing-around-twenty-three-cameras thing. Mr. Carolla even bought thousands of returned copies of his previous book and is selling sold copies at a low price to people who buy his new book.

I know what you’re thinking. How Adam Carolla’s career relevant to that of a “writer” writer? I don’t know about you, but I consider myself an entertainer. When I sit down to write, I imagine that I’m sitting in front of a stranger and I’m saying, “Check it out: I have this great story to tell you. You’re gonna love it.”

How can writers “have a motor?”

- We can write every day. I know it’s hard to sit down and to just pump out prose or lines of verse, but we really should work on something every day.

- We can understand our ambitions and act accordingly. If you never want to publish and only want to do one thing, that’s beautiful. I’m guessing I’m not the only writer out there who wants to do a number of things. I, for example, should do more GWS videos and finally start doing the podcast I’ve wanted to do for a while.

What about giving away our time and effort? I like to think that I’ve really been doing this in spades. I’ve written at least 200,000 words for GWS, all of them in the service of evangelizing for cool writing and cool writers. I love that my essays are often at the top when people search for writers or books; I’m steering at least a few people to some really cool stuff!

I’m going to have to mention the “b word:” Branding. I can’t imagine that most writers like to think about “branding” themselves, but it’s unavoidable to some extent. After all, don’t you want a reader to check out one of your poems or stories and say, “Gee…I need to see more!”

Here are some of the things that I see successful writers doing to “give away” their time and effort in hopes of a better return:

- “Selling” work for free. This is the big one, I suppose. Just like everyone else, I feel writers should be paid for their work. And I’m also very frustrated that so many wildly profitable “news” organizations don’t pay writers. Everyone BUT the writers are paid in some places. We all need to have our own policies. I am happy to give my work to publications that make no money. Literary journals? Most make zero money. If that. The vast majority of literary journal editors are doing out of love, so it only seems fair that they “pay” writers in love.

- Granting interviews and the like. I love doing my “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series because I get to give a cool writer a little attention, and the fans of that writer give me a little attention. The writers I’ve featured have been very gracious, and I think that’s how we should all be, so long as we’re not asking for too much. (I would never ask a writer for a 10,000-word essay about their theory regarding “place” in fiction.)

- Reviewing the work of others. I love NewPages and The Review Review. Karen Carlson offers interesting thoughts on literature.

What’s the ultimate goal of giving away time and effort? WE NEED TO CREATE MORE READERS. Too many people think that reading literature is for fancy-pants people. That poetry is only “when someone writes down their depressed feelings.” While Mr. Carolla knows he’s not going to get EVERYONE who hears about him, he puts his message out in a number of ways and hopes some percentage of people start to support him.

How do we offer bang for a reader’s buck?

- I’m really jealous of John Green for many reasons. (Not the least of which is that I’m revising a YA novel and I’m hoping to end up with a zillionth of his audience.) Mr. Green spends a lot of time posting videos that describe his writing process and stoke creativity in others:

Mr. Green also famously signed every copy of the first edition of The Fault in Our Stars. Mr. Green doesn’t HAVE to do any of these things. The added value, however, helps to build his audience and makes people like him all the more. What’s wrong with that?

- I’m often blown away by the generosity of many “real” writers. (“Real” as in “not me.”) T.C. Boyle is (obviously) a literary rock star, but he still spends time talking to readers on his web site’s message board. I LOVE when a writer has a solid web site. You know, they give a little bio, they give me links to find the rest of their work. I was tickled when I found Aubrey Hirsch’s site and saw a fun photo essay-type thing that she added. Again, I’m not being a zombie about “branding,” but isn’t it normal to like an entertainer who interacts a little with his or her audience?

I suppose it all boils down to the concept that Cathy Day codified as “Literary Citizenship.” While Mr. Carolla may not primarily be a “literary” guy, he follows Ms. Day’s example in the context of his comedy/filmmaking world. Within reason, Mr. Carolla does his best to truly understand the people with whom he speaks. He rejects the sound-bite shallowness that literary folks must also reject. His long-form discussions are often as illuminating as they are hilarious.

Doesn’t Mr. Carolla have what most of us want? An audience whose devotion allows him to express himself in any creative avenue he likes?

Uncategorized

Adam Carolla, Having a Motor and Getting it On, Mangria

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

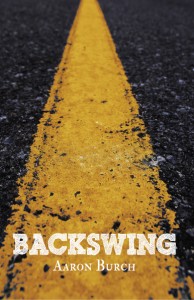

Aaron Burch may best be known as the editor of Hobart: another literary journal, but we mustn’t forget that he’s a great writer in his own right. Backswing, released by Queen’s Ferry Press, is Mr. Burch’s first short story collection. If you haven’t already done so, why not order a copy of his book from the publisher?

Sure, you might want to know about how Mr. Burch articulates his overall philosophy regarding fiction. You may want to read a 10,000-word essay in which he writes in great detail what makes a story interesting to him. Well, look elsewhere for those things. I’m really curious about some of the small choices Mr. Burch made while writing and putting Backswing together.

1) Here are some of the sentences from Backswing:

“She calls Roy, says: I have a new trick.”

“We built a fence around the remains, left it as it was in case he should return.”

“We elected Mo as recorder, made him repeat back to us, sometimes, the moments that seemed most important or confusing…”

You seem to like this sentence structure where you start with the subject of the sentence, pop in a comma and then omit the conjunction before the next verb. What’s up with that? What is the effect you’re trying to create?

AB: I do, I like that sentence structure a lot. I like the way it looks on the page, the way it sounds, the way it almost feels a little off, grabs or startles your attention a bit. I’m trying to think of where it came from, and I’ve got a few ideas. One is that it grew out of writing short-shorts: trying to make every word count; trying to cut words to, say, get down under Quick Fiction‘s 500 word limit; and also probably from Coop Renner at elimae‘s having edited pieces and showing me how I could play with language and sentence structure. The other thing that jumps to mind, and this is kinda a perfect first question/answer for “great writers steal,” is how influential Sam Lipsyte is. Venus Drive is one of those collections I go back to, over and over, probably as frequently as the nearly universally heralded Jesus’ Son. Maybe my favorite sentence (or, I guess two sentences) of all time are from “Old Soul”:

Somebody told me they were exploited. Me, I always paid in full.

I don’t know, I think the way that second sentence turns is perfect. Rereading, it’s doing something a little different than the examples you point out above, but there’s something about the comma as hingepoint for a sentence that I feel is really interesting, and I’ve probably been emulating that Lipsyte move for years. Though now, of course, I never think about it when writing, I think I just like the sound of it.

2) My story of mine that I kinda like the best has the narrator performing magic tricks. It’s really really hard to write magic tricks in fiction because the writer must conceal things the narrator knows from the audience in the story and the reader. But we can’t hide too many things or our reader won’t understand what’s happening. Your story “Prestidigitation” features a magic trick interspersed with exposition.

How’d you keep the magic clear to the reader? What were you thinking when you tried to describe something inherently visual in words?

AB: Again (and I’ll try not to add this disclaimer to every answer, we can just assume it applies across the board?), a lot of what makes it work (or, I hope it works, at least) is me playing with the story while writing it but not thinking this explicitly about what is and isn’t working, but just progressing by what feels right. Looking back now though, I think the tense and POV is pretty important here. It’s in 3rd person, but much “closer” to Roy, and is present tense, so we’re seeing Linda’s magic trick at the same time as Roy is — they’re a couple and so he knows some of the behind-the-scenes of her magic, but this is a new trick so he doesn’t know what she is going to do until she does it, so that’s where we are, too. He’s not sure what is going to happen next, but he’s curious, and he’s not just wondering what will come next but is at the same time trying to figure out how she’s doing what she’s doing. That feels like a good place for us, the readers, to be in, yeah?

That said, I did think about describing everything enough so that we could see it as much as possible. Going back, making sure where each of her hands are, what they’re doing, all of that, is as descriptive as possible so that we could follow along.

3) “Church Van” is a real cool story. There are two Roman-numeraled sections in the piece. The first one is a third person POV limited to Densmore, the protagonist. The second one is a first person POV whose narrator focuses on the reaction of the group trying to understand what Densmore was up to.

We’ve all been told a jillion times not to switch POV, but breaking that rule works in “Church Van.” Why does it work? Is it just the numbered sections? How come you didn’t just use a third person omniscient POV in the whole story?

I really think of the story as in two parts. (Though I can’t remember at what point during writing it this happened, if that was kind of always there or if it grew into that. Probably the latter, actually.) I think the story started with that first half, the idea of this dude eating a car. To again play into the idea of “great writers steal” (and also maybe over-admitting influences?), that germ of the story was more or less stolen from Harry Crews’s short novel, Car. Only, I’d heard of the book but hadn’t yet read it, and so kind of wanted to try to write a “response” to something I hadn’t actually read, see how much/effectively I could turn it into my own thing. Then, like a number of the stories in the book that are playing with more Biblical ideas, it turned into me wanting to play with the mythology of it all. I liked the idea of trying to set something up that was both the “origin story” and then the myth that it got turned into. I think the way that works, in this story, is the juxtaposition of those two sections and POVs. I actually remember workshopping this story and some comments that it might (would?) work better if the two halves were threaded together, which I guess feels more traditional, but I really like the jarringness of it this way, of how one works with and against and in response to the other.

4) “Fire in the Sky” rocks. It’s about a group of friends sharing a last night of stupid fun before one of them gets married. Something real bad happens to the groom-to-be in the story’s explosive climax. The narrator and Jeff head out on their own while things get sorted out.

I kept thinking that you were gonna have Jeff and the narrator come back to the groom-to-be. Why’d you end the story away from Hank?

AB: Again, and maybe even more than any of these other questions: intuitively. It’s actually maybe a bit more of a “short-story-y” ending in my mind than I typically like, ending with them just running, but it felt right. I don’t think I ever even considered having them return. I guess, if this were a chapter or piece of something larger, they’d have to and the story would then deal with the ramifications of what had happened, but as-is, they are just purely in the moment, which feels a nice way to end things.

5) People like me don’t have a short story collection, but we really want to publish one one day. The stories in Backswing have a mixture of POVs. It seems like an even split, give or take, between first and third with a second person story thrown in there.

Did you have this kind of variety on your mind when you put all of the stories together and put them in order? The book starts with a story about a guy who is forced to deal with his problems and ends with a story who seems to be heading out on a new adventure, leaving an old life behind. Did you do do this on purpose?

AB: Yeah, this was probably the aspect of the book I did think the most about. I really wanted it to feel like a book, not “just a collection” (as Kyle Minor says in his new Praying Drunk, albeit in a completely different way), but I also really wanted it to have a good variety. Which is maybe wanting to have it both ways, but I felt like it was possible.

When I was writing the stories individually, I want to say something super “writer-y” like I just wanted to find the POV and tense that best fit the story being told, but the reality is probably more that I was often giving myself these small challenges to try to keep from repeating myself. So…how would this story work in first person plural, etc.? And then there’d probably be a push and pull between one being adapted for and influencing the other, and vice versa, such that each hopefully did push toward using those kinds of aspects of itself toward its best benefit.

So, that’s why I had a variety of stories and, like I said, I wanted to try to find the best of way putting them together and presenting them. Which meant trying to find the “best” order for the book, and also cutting stories that maybe felt too similar and didn’t bring anything especially new to the whole, even if they were strong on their own, and that kind of thing. And also having friends read it and give input.

6) During my MFA, my awesome teachers (Lee K. Abbott in particular) advised me to use pop culture references in a smarter manner. They’re real smart and I have indeed cooled it a great deal. Sometimes, however, we just hafta use pop culture references. You start “Flesh & Blood” with a reference to Bret Michaels’ eyes and invoke “Unskinny Bop.” You mention Wall Street and Glengarry Glen Ross in the book. You mention Corvair Racers.

How do you decide when a pop culture reference should stay? What do you hope a reader who was born in 1997 thinks about the references?

AB: I probably overuse pop culture references, so I maybe could have used a teacher that told me that, actually. I find myself, in conversation but also just to myself when thinking of things, making a lot of comparisons to movies, especially, and so I find myself doing that in my stories, too. I think, too often, they’re probably used either as short cuts or just because they’re fun, so I guess the trick is to try to make them purposeful. I often drop the in to show that they are how my characters are connecting to the world, not just me, the author. As far as connecting to different generations… I guess you hope that the writing around the references is good and clear enough such that if someone hasn’t seen the “Unskinny Bop” music video, they still get what you mean and they’re not at a loss, and if someone has, it’s a bonus.

7) I am always thinking about when writers omit question marks. It’s controversial to some, but it’s a valid technique writers can employ to shape the reader’s experience.

Why’d you omit the question marks in stories like “Prestidigitation,” but you did use them in stories like “Unzipped”?

AB: Like saying I would push myself to use different POVs, I think at times it was a challenge (how to make it make sense that this story doesn’t have them, whereas this other one does?); and like me repeatedly calling out the very name of this website, it was at other times probably just because I was reading authors that didn’t use them.

Probably, mostly, it was intuitive. I think that intuition, for myself, meant using them for the more traditional “realism” stories (like “Unzipped,” “Scout,” etc.) and omitting them for the stories that felt a little more… I don’t know what you want to call them. “Experimental” isn’t quite what I mean.

8) Writers are also always thinking about how to use white space. And why to use it. And when. If you look at the middle of “Fire in the Sky” (page 87), you have your characters standing around in tuxedos and watching fireworks light up the sky. Then you have some white space before “Todd dropped a mortar into the tube.”

It doesn’t seem like much time has passed. It seems like the white space is optional and you could just have kept those two paragraphs together. How come you put white space there?

AB: I think there’s a couple things going on here. The first is that I think more time has passed than it maybe seems. They’re standing around in tuxes, watching fireworks at the beginning of the night, and then white space, and then the end of that “Todd dropped the mortar…” sentence is “…same as we’d been doing all night.” So there’s been a night’s worth of this already, during that white space break.

The second is that I try to use section breaks as not just signifiers of time having passed but as…well…just that. A “section break.” Meaning I want each piece in between those white spaces to work as its own section, almost maybe like a short-short, even, if I want to tie it back up to that first answer.

9) “Flesh & Blood” begins with two paragraphs about the teenage protagonist (Ben) noticing his burgeoning sexuality through the lens of what he sees on 1980s-era MTV.

My question is this: why do they still call it MTV when there’s no M on the TV?

Just kidding. After the reader is reminded about the thinly veiled expressions of sexuality in early music videos, you use a section break and write, “All summer, Ben has kept to his new bedroom as much as he can get away with.” That sentence introduces the protagonists, hints that he’s undergone some kind of big personal change and sets up the beginning of the school year-a transition that kicks off the narrative. In other words, it’s a rockin’ first sentence.

How come you began the story with the MTV stuff instead of the next section that really kicks off the events Ben goes through?

AB: AGAIN, like most of this, I hadn’t actually thought about this until now, but I’ve been thinking about it a lot, in how to reply. I can really only say that, for me, introducing MTV always felt like the beginning of the story. (Actually, even more specifically, it was first written with each piece of the narrative interspersed with a detailed description of that “Unskinny Bop” video, with the description of Bobby Dall’s Corvair Racer, etc. Which was super helpful for me, while writing the story, but then ultimately didn’t work. But I still wanted to open on the video.

I also think, you’re right, that second section is maybe a more traditional story opening, and does a lot of what you’re supposed to do to introduce a story. And maybe starting with MTV is not technically the best opening and over-relies on the aforementioned pop culture references, but I think that song and video are also exactly the “transition” you mention that is basically what the narrative is about, Ben’s “noticing his burgeoning sexuality,” all that. That video was 1990 and Poison was all over MTV, but within the year, “Smells Like Teen Spirit” had appeared, making Poison just about the furthest thing from cool.

Also, and maybe most importantly, starting with Bret Michaels just seemed more fun.

10) I’ve noticed that a lot of the stories in Backswing are about men who are dealing with grief in different ways, many of which aren’t necessarily healthy.

As a successful writer with a (soon-to-be) published collection of short stories, what do you think when some random weirdo tells you what he thinks your writing is about?

AB: You know… it seems kinda awesome. I think it’s often hard to know what your own stories are about, or even to see some of your own tendencies or common themes or to try to summarize your own writing. I think “about men who are dealing with grief in different ways, many of which aren’t necessarily healthy” is probably just about a better way of super briefly summarizing the connections of the stories than I could do, plus it’s obvious from the above questions that you actually spent some time with the book, and so that’s kinda exactly what you’re hoping for, I think.

Aaron Burch is the editor of HOBART: another literary journal, and the author of the novella, How to Predict the Weather, and How to Take Yourself Apart, How to Make Yourself Anew, the winner of PANK’s First Chapbook Competition. Recent stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Barrelhouse, New York Tyrant, Unsaid, elimae and others.

Short Story Collection

2014, Aaron Burch, Backswing, Queen's Ferry Press, Why'd You Do That?

Title of Work and its Form: Backswing, short story collection

Author: Aaron Burch (on Twitter @Aaron__Burch)

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: Backswing can be purchased from Queen’s Ferry Press. Click here.

Bonuses: Mr. Burch is very much a successful writer in his own right, but he is also notable for what he has done as editor of Hobart: another literary journal. Here is a story that Mr. Burch published in Storyglossia. Why not check out How to Predict the Weather, one of Mr. Burch’s previous books?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Mythological Underpinnings

Discussion:

Backswing is a cool collection of stories written by a cool storyteller. There are fourteen stories in the book and each of them has their own unique charm. It can sometimes be hard to find a table of contents for story collections, so I have compiled one for you:

|

Story Title

|

POV |

| Scout |

1st |

| The Stain |

1st (“we”) |

| Prestidigitation |

3rd |

| Flesh & Blood |

3rd |

| Fire in the Sky |

1st |

| Sacrifice |

3rd |

| Unzipped |

3rd |

| The Apartment |

1st |

| Fair & Square |

2nd |

| Night Terrors |

1st |

| Church Van |

3rd…then 1st (“we”) |

| The Neighbor |

3rd |

| After the Leaving |

1st (“we”) |

| Train Time |

1st

|

One thing that you’ll notice about Mr. Burch’s work is that he often enjoys referring to and playing with mythology. “After the Leaving” is a retelling of the Noah’s Ark story and Cain and Abel play a big role in “Sacrifice.” What does Mr. Burch gain by making explicit use of Christian mythology?

- Familiarity - I guess I’d wager that most readers are aware of the basics of these stories. Whether or not one holds the mythology as an article of faith, they’re still part of the shared cultural experience that unites us.

- Solid Narrative Foundations - Mythological stories are often fundamentally solid; if they weren’t, they wouldn’t have remained with us for thousands of years.

- Power - Mythology is all about the origins of humanity and what makes us human. These stories answer some of the biggest questions that we can possibly confront!

More importantly, Mr. Burch creates his own parables. “Church Van” is an interesting story about a man who is coping with the death of his father. Densmore deals with the loss in an unexpected and thematically appropriate manner: he buys the titular van, a vehicle that had witnessed some of his best childhood memories. Sounds normal enough, right? Well, Densmore begins to eat the van, piece by piece. The turn is accompanied by a POV shift; the narrator exists first alongside Densmore before moving to present the thoughts of the public witnesses to Densmore’s strange act of self-flagellation.

So if you distill the story to its basic elements, “Church Van” is really just a depiction of the power of repentance, a near-universal concept. Star Wars is a depiction of the battle between good and evil and the struggle we all have to escape the sins planted in us by our parents. Harry Potter is a depiction of the battle between good and evil and the struggle we all have to understand our own destinies. The Lord of the Rings is a depiction of the battle between good and evil and the struggle we all have to control our greed. Wall Street is a depiction of the battle between good and evil and the struggle we all have to control our own greed.

Gee, it’s almost as if these big stories are all pretty much the same and that you can produce something powerful if you think of your work in terms of mythology.

The stories in Backswing have thematic similarities, but Mr. Burch can’t be accused of telling the same story a dozen times. Not only does he mix up points of view, but he experiments with a wide range of settings, from the fantastic to the familiar. Perhaps my favorite story in the collection is “Prestidigitation,” a story that I happened to read when it premiered in Barrelhouse. The female protagonist of the story performs a magic trick for her boyfriend, creating a temporary alternate reality. (Isn’t that what magic tricks do?) Compare that story to “Train Time,” a first-person story in which the narrator is creating his own fantasy around the woman who sits beside him on a train. Mr. Burch also experiments with form a great deal.

“Flesh & Blood” and “Fire in the Sky” and “Scout” are “normal,” “traditional” stories. What do I mean by “traditional?” The characters are fairly “normal.” They certainly do interesting things in their stories, but there’s nothing “experimental” or “challenging” about stories populated by suburban males who enjoy golfing, pick up skateboarding or attend a bachelor party. I’m certainly not saying that there’s a negative to setting your stories in situations to which many of your readers can relate. (We all spend time with friends. We’ve all been the “new kid” in some way.) What I’m pointing out is that Mr. Burch complements these narratives with far “stranger” ones. “The Stain” is odd and cool and doesn’t take place in a world we recognize. “The Apartment” has a distinct Twilight Zone flavor.

I suppose what I’m urging us all to do is to experiment a little bit. For example, I so liked the conceit of the Aubrey Hirsch piece I wrote about that I am “experimenting” with a piece in a similar vein. While I can be frustrated by writing that is ALL experimentation, why shouldn’t we push our boundaries a little in the way that Mr. Burch does. Some stories deserve to be told in a “normal,” “traditional” way and some require us to challenge the reader a little bit with form. (Mr. Burch, of course, never leaves the audience behind when he tries something different, and neither should you.)

Here’s an interesting corollary lesson. “The Stain” and “After the Leaving” are two of the more “experimental” stories in the volume. Both are written in the first person, but the protagonist is “we.” “Us.” One of the reasons that the stories aren’t difficult to hang with is that WE are instantly aligned with the narrator by virtue of being included.

Mr. Burch’s first short story collection deserves a lot of attention because the stories are satisfying and the value of the whole is greater than that of its parts. Writers would do well to pick up a copy because Mr. Burch’s endless imagination and solid use of craft can help them improve their own work.

What Should We Steal?

- Create stories shaped by the mythology around you. Even though we’re thousands of years removed from the classical Greeks, we still feel the same deep emotions and still confront the same existential crises.

- Become adept with traditional and experimental forms. Stories are like people. Some don’t like the traditional flowers for their birthday. Sometimes, you will meet someone who prefers a copy of Mad Magazine. (Come to think of it, that’s me.)

- Offer readers a lifeline by writing in the first person “we.” Perhaps you have a bit of a crazy story or poem in mind. Uniting reader and narrator can make things a little clearer.

Short Story Collection

2014, Aaron Burch, Backswing, Barrelhouse, Hobart, Mythological Underpinnings, Queen's Ferry Press