Dear Robin Brande:

I just finished Evolution, Me & Other Freaks of Nature in a single blaze of reading and I simply had to write you to tell you how much I enjoyed the book. I bought the book from my local independent bookstore and I hope all of my cool readers follow suit.

I should be a little cross with you! =) I sat down yesterday to write the last 3000 words or so of the first draft of my own young adult novel. I figured that I would just read a little bit of Evolution and get back to my work…but your book distracted me. I didn’t resume writing until I found out what happened to Mena and how her story would end. (Don’t worry; the first draft is finished.)

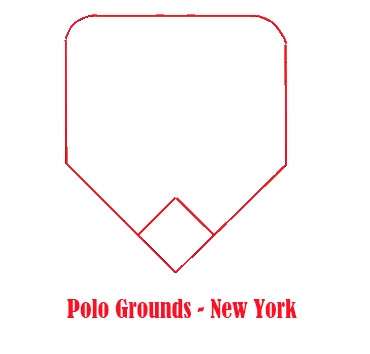

Mena Reece is a very charming character; she’s a high schooler who begins the year in a tough place. All of her old friends hate her because of a letter she sent the previous year. (Read the book to find out what it said.) She’s no longer welcome in her old church and sending the letter has put her parents’ insurance agency into jeopardy. Her life is at a low point, all because she did the right thing. Fortunately, it’s not all bad. Ms. Shepherd is a brilliant and stellar science teacher who could make a lot more money doing…other sciency things. Instead, she teaches high school because she wants to shape the minds and hearts of the next generation. Mena is also increasingly psyched about her lab partner, a young man named Casey. The two work on a big project together and, as you might expect, grow to care about each other a great deal. There’s a cool science vs. religion showdown in the classroom and a very sad scene that occurs when Mena returns to her church. In the end, of course, Mena finds a way to improve her life and to be happy by following Polonius’s greatest advice: “This above all: to thine own self be true.”

I read the first two short paragraphs of the book the night before I read the rest.

I knew today would be ugly.

When you’re singlehandedly responsible for getting your church, your pastor, and every one of your former friends and their parents sued for millions of dollars, you expect to make some enemies. Fine.

I loved the paragraphs so much that I shared them on Facebook. Why? Because you did a great job of setting up the story and preparing the reader for his or her journey. You are extremely economical in the opening:

- “I” - Okay, now the reader knows that the book is in the first person.

- “today” - You’re letting us know that the book begins on A BIG DAY. A DAY UNLIKE ANY OTHER. This is good! We know we’re not going to be bored! We’re wondering what you mean by that.

- “would be ugly” - Cool. Something nasty is going to happen today. Thankfully, the ugliness will only be in the book and not in reality.

- “you’re singlehandedly responsible for getting your church, your pastor, and every one of your former friends and their parents sued for millions of dollars” - There we go. There are HUGE STAKES for the character. People are getting sued and for LOTS of money.

- “you expect to make some enemies.” - And there are HUGE STAKES for Mena as a character. Good! This story MATTERS.

- “Fine.” - Oh, and the protagonist has some personality and is (eventually) a bit of a fighter. Fantastic. This will be fun.

Once I read those two paragraphs, I knew I was in good hands. (And yes, I did look back at the first bit of my own YA novel. It seems to me that the emotional stakes are clear and huge, but I’ll take a closer look once I type everything up.)

One of the reasons that I bought the book in the first place is that you set your story against the backdrop of the perpetual and extremely American conflict between science and religion. I happen to have been tangentially involved in this field; not in a big way, unfortunately. (I did have a piece in Skeptical Inquirer and that was a big thrill.) I was a little worried that the book might not be…compatible with reality. So I skimmed the acknowledgements and saw that you thanked Kenneth Miller. I felt better immediately. Dr. Miller, as you know, is a brilliant scientist who is also extremely devout in his religious belief. (Maybe things have changed in recent years, who knows? I’m sad to say that he’s not an acquaintance of mine.)

Evolution, Me & Other Freaks of Nature succeeds for the same reason that evolution “succeeds.” Life is complicated and messy. There are no easy answers. The only way to determine truth is to scrutinize your own beliefs and subject them to rigorous analysis. Mena is surrounded by people like the big baddie, her former friend Teresa, who see things in black-and-white. Well, the world is not black-and-white and neither is Mena’s psychology. She’s a teenager, so she really has a lot of work to do in the book to figure out a complicated representation of her identity and thoughts. Does Mena lie to herself in the book? Sure. (Especially with regard to how she feels about Casey.) But she’s always striving to reach a deeper understanding of self and of the world around her. ALL of our characters must be as complicated and as messy as possible because that’s what we all are, when you really think about it. There are no absolutes in the way people think and act, only shades of gray.

It’s a bit of a personal tangent, but I also want to thank you for the book because it took me back to 2007, when things were a little…different in the skeptic community. Things are a little…tense at the moment and I miss the way it was.

So thanks again for such a wonderful couple hours of reading. If my YA book ever gets published-don’t hold your breath-it will be fun to look back to see if any of the emotion of your book rubbed off on the ending of mine. I wish you the best of luck in the future and I admire that you’ve become such a prominent YA writer…and it all started with Mena.

Ken.

Writing Craft Recap for My Kind Readers:

- Ensure that you have HIGH STAKES in your story and that you establish those stakes quickly. The events of your narrative need to mean something BIG for your characters. That’s the only way that the reader will care about your make-believe world.

- Allow your characters to be as complicated as real people are. Remember those shades of gray. There are no absolutes in the world when it comes to people and why they act the way they do.

Find Ms. Brande on Twitter @RobinBrande. Here is Ms. Brande’s page at Random House Teen. Here is an interview she gave to Seven Impossible Things Before Breakfast, a cool book blog.

And you just know you have to check out this cool video interview:

Are you curious about skepticism and how important it is that people understand how to think critically? (This is a big theme in the book.)

Check out the James Randi Educational Foundation. Those hardworking people have been fighting irreality for a very long time. Just look at how fun and interesting Randi was on The Tonight Show. He’s demonstrating how “psychic surgeons” ply their trade. (And Randi should know; he is a world-class magician…he’s also honest about the fact that he’s doing a trick.)

What’s the Harm? is also a great resource. The next time your friend tells you that he or she is going to pay a bunch of money for “cupping,” you can find out what that is and why having it done doesn’t make any sense.

Dr. Harriet Hall is an MD who writes about alternative medicine and the like.

And no critical thinker should be without the works of Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens. We may not always agree with everything a great thinker says, but we ignore them at our own peril.

Novel

2007, Christopher Hitchens, Robin Brande, WriteAWriterDay

Dear Chana Bloch:

I am writing to share my admiration for your work and, specifically, for

“The Little Ice Age.” It’s very kind of you to let people read the poem on your web site after its appearance in the Spring 2011 issue of Field. (Readers can also access the poem through EBSCO.) I also admire that you’ve posted an MP3 of yourself reading the poem; what a great way to help writers understand the difference between the written and spoken word.

You’ve done an awful lot of good for the poetry community and young writers are certainly advised to emulate the spirit in which you share your work and your thoughts. I happen to be a writing teacher (of far less renown, of course) and you must get a great satisfaction out of knowing how many thousands of writers have improved their craft because of your generosity.

As for your work, I love poems about history and science. I’ve written a few myself, though I don’t think any have been published. “The Little Ice Age” consists of two five-line stanzas. In the first, you paint the picture of what human existence was like during that event. In the second, you describe a beautiful and unintended consequence of that massive chill.

I love the way that you populate that first stanza with those two-word stings in the midst of the two longer sentences. Each of these phrases (but one) have the same construction: noun + verb.

Europe shivered

Rivers froze

crops failed

people chewed

people starved

This technique seems effective to me for at least a couple reasons. The “noun + verb” is very direct and very clear. Yes, these were the terrible consequences of the cooling across Europe. Alternate sentence constructions may not be as direct and convincing. Further, the “noun + verb” settles the matter. You’re letting us know that the poem is not part of a debate between climatologists; you’re just telling us what happened. Further still, the simple construction puts emphasis on those sad and powerful verbs. “Shivered,” “froze,” “failed,” “starved” …these are generally not happy verbs.

Goodness, and you use such a wonderful verb in the second stanza to describe the sound of a Stradivarius. Here is where you can hear a Stradivarius “cry” (albeit filtered through digital compression):

I admire the overall construction of the poem, as well. Two stanzas. Cause, then effect. The harshness of the climate resulted in the kinds of trees that Stradivarius needed to create his instruments. “The Little Ice Age” teaches scribblers such as myself how each stanza should contribute to the poem as a whole.

The baseball season is nearly upon us. A pitcher can’t think of each pitch as an isolated throw; he must decide what to throw based upon a vast number of factors. One of a pitchers big weapons is a change in velocity. Justin Verlander, for example, will blow a 100-mph fastball right past a batter, then drop an 81-mph changeup. The hitter doesn’t have a chance.

How does this relate to your poem? I admire the way that your first stanza sets up your second in the same way that a pitcher on my team causes a batter’s knees to “buckle.”

Thanks again for your poem and for all you have done for other writers of poetry and prose. I wish you the best in 2014 and beyond.

Ken.

Writing Craft Recap for My Kind Readers:

- Employ a simple “noun + verb” construction to solidify points that aren’t up for debate in your piece. This technique ensures your work will have brevity and allows you to steer focus to what really matters to you.

- Consider the function of your stanzas in the context of the work as a whole. Stanzas are to poems what paragraphs are to prose. Each of the smaller parts should contribute meaningfully to the operation of the larger machine. Follow a fastball with a slider or vice versa.

Poem

2011, Chana Bloch, Field, Ice Age, WriteAWriterDay

Dear Molly O’Brien:

I am writing to let you know that I admired your story, “Casual, Flux.” I found it on Paper Darts and I think they did a fantastic job with the design of the piece.

Science fiction stories happen to have been my first love and your story has a decidedly SF flair. One of the big problems that a writer has when composing this kind of piece is that he or she must create a whole new world and a unique society in the space of only a few sentences. I admire the way you hit the ground running in “Casual Flux.” Here are the first few sentences:

Girl 23 and Boy 41 are sitting in Boy 41’s kitchen. It is 3:24 a.m. Boy 41 swirls warm bourbon in an IKEA drinking glass. They are recapitulating a humorous conversation from a party that occurred earlier tonight.

Two months ago, I made my initial 5-day observation and entered the assessment data into the Orcon database.

I love that we meet all three characters: Boy, Girl and the voyeur in the first sentence. You offer all of the details we need to know that the watcher is doing so in some kind of official or scientific context. You give us the time and phrases such as “5-day observation,” “assessment data” and “Orcon database,” the last of which makes it clear that the narrator is working for some kind of shady company or extraterrestrial agency. (I’m fine with either one.)

The point is that you are wise enough to set up the “unusual” aspects of your world in an efficient manner, allowing you to get to the actual STORY. And what a fun story it is. Even though I’m retired from the game myself, I love a good love story. What’s the problem? There are so darn many love stories out there! Have you done something completely new with this story? Of course not. There’s simply no way to write a brand-new romance. But I wanted to tell you that I admire that you clearly looked at a very normal situation (a boy and a girl taking their relationship to a new level) and looked at it from a different perspective. Instead of making Boy or Girl your first person narrator, you’ve added a little spice to a story that may otherwise be a little bland.

Do you like Sara Bareilles? I like Sara Bareilles. She’s incredibly talented and she writes great songs. From what I understand, her record company encouraged her to write a love song that they could turn into a quick and easy single. Did she come up with an “I Will Always Love You” or a “Without You?” Nope. She came up with “Love Song.”

Like “Casual, Flux,” Ms. Bareilles’s “Love Song” can be classified as a love story, but you and Ms. Bareilles keep us interested by doing something special with the concept. Something that we can’t get from every other Celine Dion ditty.

So thanks again for such a cool story; I truly enjoyed spending a little time in the world you created. Best of luck in your future endeavors!

Ken.

Writing Craft Recap for My Kind Readers:

- Establish your unexpected conceit as quickly as possible. When you are working in a world that is different from our own, you need to orient us immediately.

- Put your own spin on a story that may otherwise be formulaic. There are no new stories under the sun; what should make us want to read your spin on a human event that has happened many times before?

Short Story

2014, Molly O'Brien, Paper Darts, Sara Bareilles, WriteAWriterDay

Dear Roddy Doyle:

I am writing to let you know that I admire your work. I read The Commitments several years ago and admired it greatly. At the moment, however, I would like to tell you how “Guess Who’s Coming for the Dinner” offered me a brief moment of relaxation that I truly needed and what the story taught me about writing craft.

This time of my life is very stressful. I’m bogged down by some of those family issues that can sometimes hold us rapt for decades. I’m not where I would like to be in my career. I have been so unsuccessful in romance that I’ve just given up on the prospect of ever having a happy relationship. (I hasten to point out that the blame is entirely mine.) A few days ago, I picked up a copy of The Deportees and Other Stories. The book, thankfully, lived in my car until a few mornings ago, when I found myself up and about at a very early hour in frigid Oswego, New York. I decided to go to a local diner to have a good, old-fashioned American breakfast. Needing something to read, I brought The Deportees with me to the table. My goodness, my problems were gone for an hour and a half as I read a bunch of the stories in the volume. Instead of spending time alongside money and personal concerns, I passed the time with Larry the loving father, the unnamed young man in love with a Nigerian girl and Alina the nanny. I love the generosity with which you treat all of your characters and the way you treated your marginalized characters. At no point are you preachy and boring; the immigrants are real people who simply happen to be from elsewhere.

I also have to admit that I’ve always had a soft spot for Ireland and its writers. I spent a wonderful week in your country many years ago and instantly fell in love with the Emerald Isle’s people, food and beer. (Even the weather, though rainy, suited me just fine.)

Most of all, I am writing to thank you for teaching me about writing craft through your story. “Guess Who’s Coming for the Dinner,” originally published in serial form in Metro Éireann and later revised for The New Yorker, is about Larry Linnane and his family. Larry prides himself on his very progressive outlook on life. He acknowledges that his grown daughters are human beings and have sex lives and he loves his wife Mona as an equal. Then his daughter Stephanie mentions Ben, a Nigerian immigrant with whom she has been spending time. As was the case in the movie from which you borrowed, Larry suffers a number of internal conflicts regarding his daughter’s relationship with a black man. I don’t want to ruin too much of the story for my readers, but the story is most certainly a fresh look at the subject matter. (And it’s a lot of fun.)

It’s definitely a very small issue, but it’s one about which I care deeply: what are writers to do with alternative methods of casting our dialogue? As you know, many writers eschew quotation marks completely, which adds some ambiguity at times. (I sometimes feel as though the writer is challenging me to put them in so I can know which words are spoken by the character and which aren’t.) You used the same technique in “Guess Who’s” that you did in The Commitments, placing em-dashes before each line of dialogue. I admire the way that this choice keeps the lines flowing while keeping the reader informed as to when he or she is reading words that are spoken by characters.

I knew when I read the introduction to your collection that I was going to enjoy the stories. The brief comments make it clear that the stories were going to be about interesting social developments in Ireland and that you were going to tell me real stories about real characters; you saw that your message was clearly subordinate to your responsibilities as a storyteller. Further, I loved the conceit of all of the pieces. You wrote 800-word chapters as your deadline approached. Sometimes, this resulted in what you call “tennis racket moments,” a reference to the “character in a U.S. TV daytime soap who once went upstairs for his tennis racket, and never came back down.” Perhaps it was unintentional, but you’ve offered your fellow writers wonderful advice. Even if our stories aren’t published in serial form, it’s a very good idea to set a deadline and to just WRITE, regardless of the loose ends that we can see poking out of the story as we compose.

Most importantly, your writing is FUN. During that lonely diner breakfast, I read a horror story, an amusing family drama that ends somewhat unexpectedly and a story about a teenage boy who demonstrates his love for a young Nigerian woman in a way that I couldn’t have anticipated. I can’t say that I’ve read all of your work, but it is safe to say that you have a wide readership because you appeal to our hearts and our minds in equal measure. Books such as yours surely capture a great number of readers who may not yet fully understand the awesome power of literature.

So congratulations on all of your well-deserved success and I wish you the best of luck in 2014 and beyond.

Respectfully,

Ken

Writing Craft Recap for My Kind Readers:

- Hold your reader’s hand at least a little bit when it comes to dialogue. So you want to make the artistic choice to omit quotation marks? Smashing. Just make sure you give us some easy way to know when your characters are talking.

- Compose in serial form…even if that’s not how your work is eventually published. Add 1000 words a week to a story each week and you’ll have a great first draft in a month’s time. (That draft will probably be filled with dramatic peaks, too!) Ignore the little mistakes that you notice along the way.

- Make sure your work is FUN! We need to win back the proverbial “woman on the bus” who falls into her seat after a long day of work and reads a story on her way home.

Short Story

2001, GWS Presents: Write a Writer Day, Roddy Doyle, The Deportees and Other Stories

Friends, writing is a solitary pursuit. Even if we’re lucky to be a part of an MFA community or the member of a writers’ group, nothing happens until we sit down and put our fingers on the keyboard or pen to paper. And when we’re lucky enough to share our works with the world, we seldom get enough recognition. We reach readers, but they don’t always reach us.

Now there’s Write a Writer Day.

On April 23rd (Shakespeare’s assumed birthday), we are going to e-mail, tweet and even compose letters to the writers who change and enrich our lives. Are you in?

Check out the WAWD page here at Great Writers Steal. You’ll find some frequently asked questions and some dos and don’ts.

Follow WAWD on Twitter to get the latest and to share your own ideas.

Like WAWS on Facebook for additional news that isn’t restrained by the 140-character limit.

Comment below to share your ideas as to how we can reach as many writers as possible!

Uncategorized

Title of Work and its Form: “Albert Arnold Gore,” short story

Author: Aubrey Hirsch (on Twitter @aubreyhirsch)

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in an online edition of American Short Fiction. You can read the story here.

Bonuses: Here is an interesting piece of science fiction that Ms. Hirsch published in Daily Science Fiction. Why not check out Ms. Hirsch’s first short story collection, Why We Never Talk About Sugar? You’ll also want to find out about her split chapbook. This Will He His Legacy was published by Lettered Streets Press. (You’ll also get pieces written by Alexis Pope!) Want to see a video interview Ms. Hirsch gave to PANK?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Public Figures

Discussion:

The story consists of three vignettes, each centered upon one of the Gore men. Albert Arnold Gore, Sr. was, of course, a Senator from Tennessee. Al Gore, Jr. was the Vice President under Clinton. Al Gore III is a business executive who, as of yet, has not entered the same public life as the earlier Al Gores. In the first vignette, Ms. Hirsch turns her focus to the philosophy by which Senior conducted himself as a father. In the second, Al Jr. is urged to enlist in the military in order to buffet Senior’s electoral hopes. In the final section, Junior teaches III-a young man who famously suffered a terrible car accident-how a man should fight and when.

Ms. Hirsch “steals” in glorious fashion in this piece. She is, of course, making use of the lives of public figures. The Gore family has been prominent in American politics for several decades. They have, to some extent, offered writers their identities. It’s perfectly acceptable, within reason, to transform these public figures into characters in our work. Sure, you probably can’t write a story in which you cast a real-life politician as a pederast or something equally abhorrent. (Think about what Law & Order does. We all know that the Monster of the Week is, say, Paula Deen. The writers, however, have renamed the Southern Lady who’s in trouble for using racist terminology. It’s not Paula Deen…it’s Maura Feen.)

By all means: write a short story about what Winston Churchill was doing while the Battle of Britain raged. Write a poem about William Henry Harrison coughing on his deathbed. We’re all curious as to what it’s like when Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt take their children to a casual dining restaurant. (Spoiler alert: I’m guessing a lot of Cheerios get crushed on the table and that they leave a big tip.)

Feel free to consult an attorney, of course, before you write your 500-page novel about Jessica Alba. It’s my understanding that public figures have a lower expectation of privacy than do private citizens. You’re well within your rights to fictionalize the life of a celebrity so long as you don’t stray into libel or slander or defamation of character. (I’m also under the impression that you have a lot more leeway with people who are long dead.) Ms. Hirsch is certainly well within her rights in “Albert Arnold Gore.” The story is an act of scene making based upon speculation derived from well-known facts.

It just so happens that I read a Roddy Doyle this morning in which his protagonist refused to provide his own name or those of his friends. This may be a logical move for the protagonist, but it could be a problem for a writer. After all, the reader needs to know which character is speaking and acting. Ms. Hirsch has a similar problem in “Albert Arnold Gore.” All of the characters in the story are named Albert Arnold Gore. Now, the three vignettes take place at very different times. The Albert born in the 1980s can’t be confused with the one who is being encouraged to enlist and go to Vietnam. Time just doesn’t work that way…yet. Someday. Still, there’s an awful lot of “Al” in this story. How does Ms. Hirsch manage to keep everything straight?

- Dates - The first sentence makes it clear that the section takes place in 1930. The third, we’re told, takes place in 1991.

- Generational Suffixes - There’s Senior and Junior and III. The suffixes keep things straight in the story, just as they do in real life.

- Clear Section Titles - Ms. Hirsch could have been a little less clear. Instead, she helps us out by naming each section after the Albert Arnold Gore whose POV is employed within.

There’s a bigger point to be made. It’s true that Ms. Hirsch is careful to keep the prose clear, but there’s an inherent and appropriate confusion in the story. Each character is named “Al.” Just as in real life, such a situation strips a little bit of individuality from each Al. Each of these men have made respectable lives for themselves, but they are inextricably linked by their names. Isn’t this the whole point of naming a kid for his or her mother or father or grandparent or family friend or dead aunt or uncle? When future Vice President Al Gore and his then-wife Tipper named their child Al Gore, they were imprinting slight expectations and some kind of identity onto the child. And why not? Al Gore I accomplished a great deal of good. Al Gore II was already in Congress when III came along. I’m betting that III may feel a little bit of pressure, but being III also has its advantages. The repetition of “Al” may give the reader a slight sense of disorientation, but it’s okay in this case because Ms. Hirsch is careful tokeep things straight.

What Should We Steal?

- Cast a public figure as your protagonist. What did President Bush (41) say to his aides after his mission in Iraq was accomplished? What did President Bush (43) say to his aides after his mission in Iraq was accomplished?

- Address possible sources of confusion in your work. There’s a reason why we avoid populating a story with characters whose names are Mary, Marilyn, Maribel, Marie, Marianne, Maryanne, Maria, Marielle, Moira, Mariah, Mareyea, Miriam, Marian, Molly, and Marty.

Short Story

2011, Al Gore, American Short Fiction, Aubrey Hirsch, Public Figures, Why Did He Wait Until After the Election to Showcase His Personality?

Title of Work and its Form: “Divine,” poem

Author: Kim Addonizio

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem was first published in the Spring 2012 issue of Fifth Wednesday Journal. The incredible Denise Duhamel and David Lehman chose the poem for the 2013 volume of Best American Poetry.

Bonuses: Poet John Gallagher offers some excellent analysis of the poem; there’s also an interesting discussion in the comments. Ms. Addonizio is EVERYWHERE, folks. Here is her Poetry Foundation page. Here is an interview Ms. Addonizio gave to Poetry Daily. Poetry, of course, is usually best enjoyed in performance. Here are some examples of the poet reading her work:

Ms. Addonizio is certainly a fascinating woman; here she is performing with a blues band:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Free Verse

Discussion:

Guess what. You’re stuck in the dark woods, a place where you are at risk of being flayed by werewolves and of meeting those creatures humans have created to keep their children in line. Ms. Addonizio addresses YOU in the poem, using that second person swag to immerse you in a place rife with:

black trees

hung with sleeping bats

like ugly Christmas ornaments.

As the poem ends, “you” are left impotent and alone in a scary and dangerous place.

Okay, so this poem is in free verse. Even though I love poetry (and all writing) of all kinds, free verse has always been a bit of an enigma to me. There isn’t much obvious structure, is there? No meter, no rhyme. As Robert Frost said, writing free verse is like playing tennis with the net down. Ms. Addonizio’s poem is a good example of how free verse DOES have a structure and how poets are definitely working within a series of rules in order to create.

Here’s the big lesson that fiction writers and other free verse averse folks can learn from “Divine.” Even though the poem somewhat resembles a stream-of-consciousness explanation of a dream, each line of the poem is interesting. Each line is a little poem unto itself.

Prose writers can take hundreds of thousands of words to make their ultimate point; poets have a far smaller canvas. There’s a lot more margin for error in a short story, too. So a sentence sounds crummy to the ear or a paragraph represents a little bit of a tangent…that’s fine. There are countless additional opportunities for the writer to impart meaning.

Poets don’t have that luxury. That’s why Ms. Addonizio ensured that each line had SOMETHING going for it…even if it’s only two words long.

oozing mayonnaise.

See? Two words long. Why shouldn’t Ms. Addonizio have simply hit “backspace” to put those two words on the previous line? In this case, the words evoke a very powerful and visceral image. (And a gross one.) Oozing mayonnaise. Ew. The line also forces you to exercise your lips. Read it aloud. You have to go from the OOOOO to the AAAAAHHH. Your lips pursed, then your mouth completely open.

Another example:

If you had a real one you could stab

Okay, okay. What do we appreciate about this line in isolation? Well, it sets up the next line, allowing “your undead love” to exist on its own. I also love the momentum of the line. Commaless, we run into that powerful verb without much warning. “Stab” is a scary verb, isn’t it?

I also admire that the poem is abstract…but not too abstract. Reading some poems, you’ll agree, make you feel as though the poet is daring you to get some meaning out of the lines. (My students often experience this sensation. It’s an unpleasant cycle. The only way to “get better” at reading poems is to…read poems.)

Ms. Addonizio mentions that “you watched the DVDs that dropped/ from the DVD tree.” Someone like my father-a smart man, but not much of a poetry reader-might struggle with the abstraction momentarily. There’s no such thing as a DVD tree! But when you think about it for a while, having been primed by the other “fantastic” concepts Ms. Addonizio uses in the poem, it kinda makes sense. You can conceive of some kind of “DVD tree.” (And if you think about it, is Redbox all that different from a DVD tree?)

Ms. Addonizio writes,

Ping went your iHeart

What?!?!? There’s a new product from Apple called the iHeart? type-a…type-a…type-a…type-a…type-a…wait for the network…click-a…click-a…click-a…click-a…

Hey, there’s no iHeart scheduled for release! Oh…Ms. Addonizio is making a comment about the rote, mechanical nature of romance and attraction to which we all sometimes fall prey. See? The accessible abstraction allowed her to engender complicated and interesting thought. (And she was able to do so with just six characters!)

What Should We Steal?

- Make the most of each line, particularly in free verse. Go through each line to make sure there’s SOMETHING for the reader to enjoy.

- Keep your abstraction accessible. Even if you never meet the person who is reading your poem, you are still performing for them. You don’t have to take them by the hand…but you should at least hook your pinky into theirs as you lead them along.

Poem

2012, Best American Poetry 2013, Fifth Wednesday Journal, Kim Addonizio

Title of Work and its Form: “A State of Feeling,” creative nonfiction

Author: Rachel Luria

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece was published in the Spring 2013 issue of Phoebe. You can read the piece here.

Bonuses: Ms. Luria was one of the editors of Neil Gaiman and Philosophy; why not check the book out at Powell’s? Here‘s a PopMatters review of the book.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: In Medias Res

Discussion:

Ms. Luria was feeling the deep loneliness to which many of us can relate and was hoping to find companionship. So she went to Dragon*Con, a gathering of folks hoping to celebrate “all things science, science fiction, fantasy, and horror. (I haven’t been myself, but I’m guessing it could be a lot of fun.) Ms. Luria was under the impression that she would find her soul mate at the conference, saying, “If I can’t find a man at Dragon*Con, then I am definitely going to die alone.” Ms. Luria describes her experience in speed dating and how she felt when surrounded by all of the other attendees. The account is interspersed with vignettes exploring the depth of her loneliness; she went quite some time without being in a relationship and struggled with the internal and external stresses resulting from such a condition. Near the end of the piece, we learn that Ms. Luria’s loneliness was broken when she met someone online and that her day as a zombie bridesmaid represented a fairly low point in her life whose emotions never truly leave her.

Ms. Luria makes a wise choice in beginning her piece “in medias res.” (That’s Latin for “in the middle of things.”) Instead of describing how she registered for Dragon*Con or the boring and commonplace process by which she got to Dragon*Con, she begins with a scene that finds her standing outside of the conference hotel. Two young men are offering hugs; some “awkward” and other “deluxe.” Not only is her mid-scene opening a good idea because it immerses us quickly in her narrative, but also because she chose a very good anecdote. These young men are probably a lot like many video game/comic book nerds. There are certainly exceptions, but these folks are often socially awkward and aren’t often at the top of the list when women decide who they want to date. (The popular perception and the way society treats them doesn’t exactly help them in this regard, does it?)

Like the author, these young men are hoping to find a connection…possibly a romantic one. This opening anecdote primes us perfectly for the overall theme of the piece. Ms. Luria is lonely and she’s surrounded by people who are also somewhat adrift. The opening of “A State of Feeling” teaches us two important lessons in one: prose writers may wish to begin in the middle of the drama and they are also well-advised to choose anecdotes that tie strongly into the theme of the overall piece.

“A State of Feeling” has at least one thing in common with Kent Russell’s excellent “American Juggalo.” Both nonfiction pieces feature stories that are told by someone who is at once part of the group they’re analyzing while maintaining a kind of distance. Yes, Ms. Luria took place in the Dragon*Con speed dating. Yes, she talked to a guy who was dressed like Luigi. She doesn’t, however, bore us with the mundane parts of her time. Did she go see the Firefly panel? Maybe. I’ll bet she ran into an actor who has appeared on Star Trek. She didn’t tell us about these moments because they didn’t fit the tone that she took. She’s IN the Dragon*Con world, but not OF it.

Why is this a shrewd choice? Taking this stance allows her some objectivity. The distance helps her to contextualize her feelings, both about herself and those around her. Maintaining this distance can be very difficult, particularly when writing creative nonfiction. I’ve written a little bit about my somewhat challenging family situation and it’s really easy to slip into pathos when logos and ethos are a better overall fit. We care that she feels lonely, but we’re not going to understand it unless she can describe it from a writer’s perspective.

What Should We Steal?

- Begin the narrative in the middle of the story and with a thematically significant anecdote. Doing so weeds out the boring parts and gets us to care about your characters very quickly. (This is especially true if YOU are the character!)

- Describe your personal experiences as a writer, not as the individual who experienced them. Your humanity will bake the emotion into your writing all by itself; it’s your job to use your rhetorical skills to make us understand what the experience truly meant.

Creative Nonfiction

2013, Dragon*Con, in medias res, Phoebe, Rachel Luria

Title of Work and its Form: “The Wilderness,” short story

Author: Elizabeth Tallent

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was first published in Spring 2012’s Issue 129 of Threepenny Review one of the top journals out there. Elizabeth Strout (and Heidi Pitlor) chose the story for the 2013 edition of Best American Short Stories and it can be found in the anthology.

Bonus: Here is what Karen Carlson thought of the story. Here is “Little X,” a piece of memoir that Ms. Tallent published in Threepenny Review. Here is Ms. Tallent’s page at Powell’s Books.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Compensation

Discussion:

The third-person protagonist of the story is an English professor who is endlessly fascinated by her students’ preoccupation with machines. The young people are seemingly addicted to the bleeps and bloops that make it clear that the devices are alive. The professor was enthralled by a different object as a child: a mummy that helped her understand death and the meaning of history. The strongest bit of narrative relates to this struggle between history and inanimate objects: Wal-Mart wants to plow over the woods of The Wilderness to build a new story. The narrator’s great-great-grandfather nearly became a casualty of war on that ground. The story ends as the narrator reconsiders what it means to elude death and to live life. (It was also my impression that Ms. Tallent makes the case for literature in the story; Shakespeare’s body was not immortal, but he’s still with us and will be until the final human breathes his or her last.)

We can all certainly agree that “The Wilderness” is not a white-knuckle barnburner with a complicated plot. We’ll also agree that plot is an important part of a story. So why aren’t we upset with Ms. Tallent? It’s easy: she makes more potent use of the other tools in the writer’s toolbox in order to compensate. We all love the eerie inevitability of the plot of “The Lottery,” for example. Stuff is always happening in that story; people file into the town square, slips are drawn from the box, and men, women and children pick up stones. The narrative thread of “The Wilderness” is not as strong as that of “The Lottery” and that’s perfectly fine because Ms. Tallent offers extremely potent characterization to help us understand the professor. Ms. Jackson’s sentences in “The Lottery” have a beauty about them, but the sentences must, by necessity, take a backseat to the plot. Unbound by a similar obligation, Ms. Tallent offers us sentences that are a joy unto themselves.

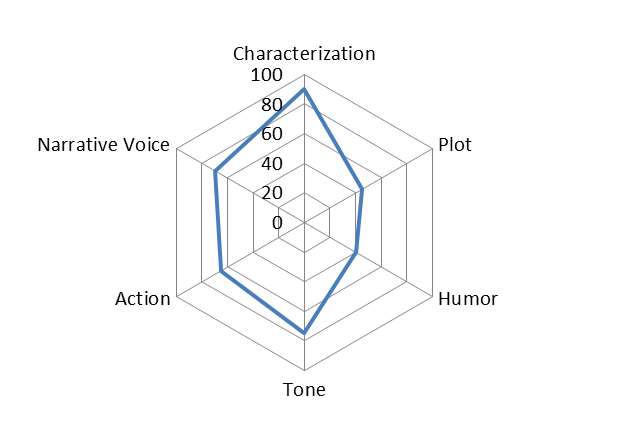

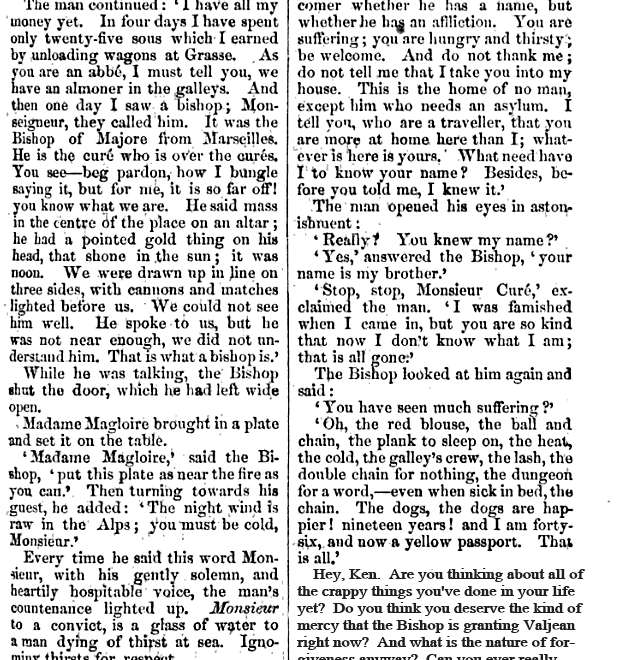

Here’s a chart I made for a previous essay that illustrates my point. (I would love to believe that every GWS reader has gone through every essay, but I know it’s not the case.) A story is like a spider web or a net. A web or a net can have odd dimensions and it can even have holes, so long as the other parts of the structure are strong enough to hold it together. The plot of “The Wilderness” may not, as Nigel Tufnel might say, go to eleven. Other facets of the story, however, DO go to eleven (which is one louder), ensuring that the story is coherent and enjoyable.

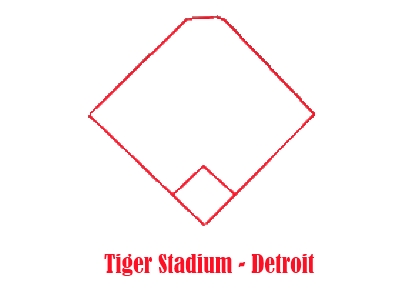

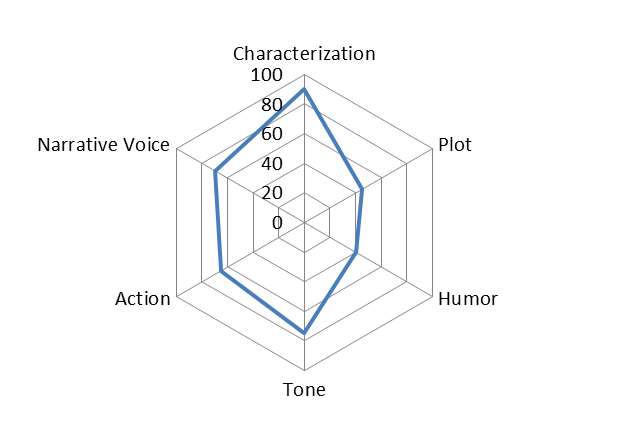

Let’s think of it another way. Spring Training is going on as I write this. (My beloved Tigers are trying to figure out what they are going to do at short.) Until 1999, the Tigers played baseball at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull, filling the stands of the most beautiful ballpark ever. Look at the dimensions of Tiger Stadium:

Let’s think of it another way. Spring Training is going on as I write this. (My beloved Tigers are trying to figure out what they are going to do at short.) Until 1999, the Tigers played baseball at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull, filling the stands of the most beautiful ballpark ever. Look at the dimensions of Tiger Stadium:

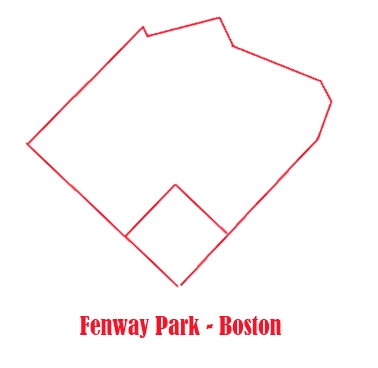

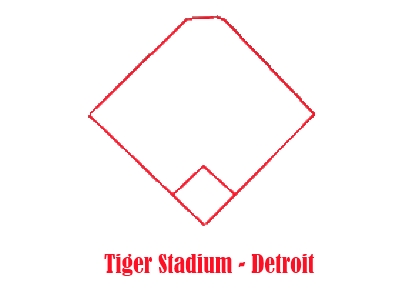

See how even? See how beautiful? Now THAT’S an outfield. Baseball is a rare sport whose playing field isn’t completely regulated by the rules. Yes, the bases must be ninety feet apart, but the shape and dimensions of the outfield vary wildly between ballparks. Think about Fenway Park. The builders had a bit of a problem: the street running along left field was very close to home plate. See:

See how even? See how beautiful? Now THAT’S an outfield. Baseball is a rare sport whose playing field isn’t completely regulated by the rules. Yes, the bases must be ninety feet apart, but the shape and dimensions of the outfield vary wildly between ballparks. Think about Fenway Park. The builders had a bit of a problem: the street running along left field was very close to home plate. See:

How did the builders compensate? Why, they made the left field fence extremely high. (It’s that “Green Monster” you’ve heard so much about.) If that fence were five feet high, each Red Sox home game would have a score of 23-22.

How did the builders compensate? Why, they made the left field fence extremely high. (It’s that “Green Monster” you’ve heard so much about.) If that fence were five feet high, each Red Sox home game would have a score of 23-22.

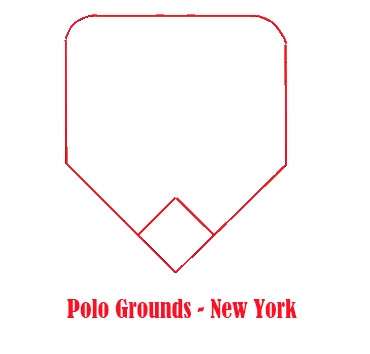

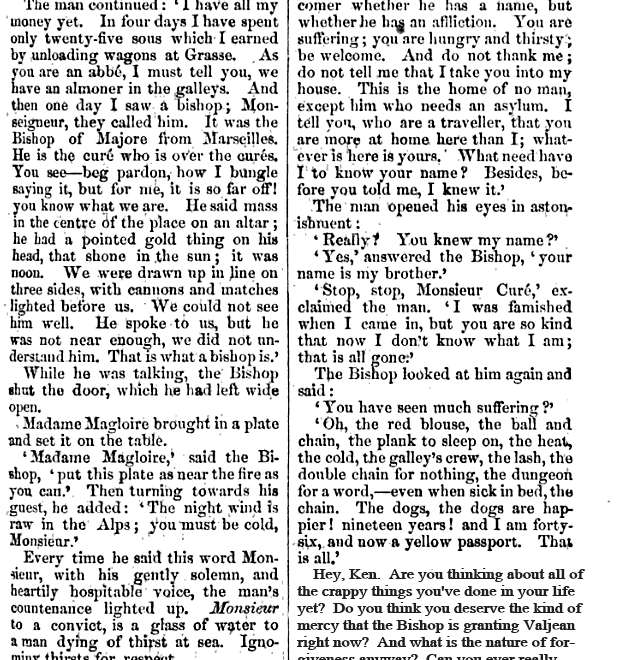

Check out the dimensions of the Polo Grounds, the former home of the New York Giants (and briefly the Yankees and Mets).

No, you’re not seeing things. You’re seeing why they called it the “polo grounds.” Each foul pole was really close to home plate, so the fences were higher. The Giants also compensated for those generous porches in right and left by making center field a vast wasteland where home runs go to die. (Or to turn into doubles.)

No, you’re not seeing things. You’re seeing why they called it the “polo grounds.” Each foul pole was really close to home plate, so the fences were higher. The Giants also compensated for those generous porches in right and left by making center field a vast wasteland where home runs go to die. (Or to turn into doubles.)

Wasn’t that a fun and unexpected way to consider my point? When one facet of our work is, by design, a little weak, we must compensate by adjusting the prominence of the other facets. Would Alfred Hitchcock have chosen “The Wilderness” as the basis for his next suspense film? Probably not. He would, however, have admired the story’s depth of characterization and its philosophical underpinnings.

Another facet of “The Wilderness” that I admire is the way that Ms. Tallent encouraged me to think about BIG ISSUES in a graceful manner. She made her character think about them first. “She” doesn’t seem to have liked her former colleague very much, but his flirtatious question has had her thinking ever since he asked what she would want on her tombstone. Now, Ms. Tallent is not forcing us to think too much. That would be a violation of the writer’s First Duty. (It’s the writer’s job to do all of the work so the reader can have all of the fun.) Ms. Tallent is, however, inviting us to think big thoughts. Invitations are fine; dictates are not.

Have you ever been asked, for example, which three books you would take with you to a desert island? Which family member would be the first you rescue from a burning building? These are difficult questions to answer when you’re put on the spot. Instead, Ms. Tallent simply offers up the question for her character; we can choose whether or not we want to address it.

What Should We Steal?

- Boost the power of other parts of your work when another part is a little weak. Okay, so you’re writing Transformers 8: The Planet of the Machines. Each of the characters are named “Guy” and “Girl” because the characters in the Transformers movies are irrelevant. There better be some pulse-pounding action scenes in the script to make up for it.

- Ensure that any deep thought on the part of the reader is voluntary and earned. I think about the nature of humanity and our responsibilities to each other when I read Les Miserables. I probably wouldn’t do so if Victor Hugo did something like this:

Short Story

2012, Best American 2013, Elizabeth Tallent, Narrative Compensation, Threepenny Review

Title of Work and its Form: “Nemecia,” short story

Author: Kirstin Valdez Quade

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was first published by Narrative Magazine. You can find the piece here. “Nemecia” was subsequently chosen for the 2013 volume of Best American Short Stories.

Bonus: Here is “The Five Wounds,” a story Ms. Quade published in The New Yorker. Here is another story Ms. Quade published in Guernica. Here is what cool writer Karen Carlson thought of the story.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Objects

Discussion:

Maria looks back on the time she spent with her cousin Nemecia with a kind of bittersweet love. The title character suffered a terrible family tragedy, necessitating a move to Maria’s home. Many years have passed since the two young women lived together; Maria (the first person narrator) wasn’t always happy that her cousin was around. And why would she be? Nemecia got all of the attention because of the misfortune she experienced. Nemecia is older and eats ravenously. Ms. Quade includes a beautifully written example of another of Nemecia’s crimes: she would dig her thumbnail into Maria’s cheek each night, creating a scar. Maria can only take so much; after her cousin ruins one of her rites of passage, she says something she can’t take back and is sent away for a little while. In the present day, Maria remembers Nemecia with the understanding she couldn’t muster in her younger years.

Ms. Quade knows she has a lot of exposition to dole out. In addition to the expected basics, she needs to let us know when Maria is telling the story. She needs to place the dramatic present of the flashbacks. She needs to set up the “mystery” of Nemecia’s tragedy. Perhaps her most difficult move: Ms. Quade needs to establish the different attitudes Maria holds as a grownup and as a child. What is Ms. Quade’s first move? How does she streamline some of the exposition? What device does she use that allows her to explain a lot in a felicitous manner? A photograph. The story begins,

There is a picture of me standing with my cousin Nemecia in the bean field. On the back is penciled in my mother’s hand. Nemecia and Maria, Tajique, 1929.

The photograph is a very logical entry point for the story. Not only is it a firm piece of documentary evidence-it’s a picture, after all-but it nudges the reader into something of a visual mindset, mimicking the response he or she might have if they were actually looking at a picture. Another reason that the photograph works is that these objects are (by definition) representations of the past. After absorbing the mental image, we’re primed to enjoy a short story that takes place primarily in flashback.

So, a spoiler alert would be inappropriate when I tell you that Nemecia is dead at the time when Maria is recalling the story. Here’s why it’s not a problem. This kind of rote statistic really isn’t important for Ms. Quade’s purposes. It seems that the author’s intent was to tell us a meaningful story about Nemecia and the relationship between the cousins. It really doesn’t matter what jobs Nemecia may have had in her working life or how old Nemecia was when she passed. All that matters is what happened between the women when they were teens and how the two (especially Maria) learned to understand the other on a deeper level. I don’t believe Ms. Quade tells us the name of Nemecia’s husband…but that doesn’t matter. We DO care that Nemecia has apparently changed her name as part of the process of leaving her past behind.

Think about the Star Wars prequels. (But just for a moment. Then you can go back to pretending they don’t exist.) When The Phantom Menace was released, we all knew quite well how Anakin Skywalker/Darth Vader met his end. All of that suspense was already gone as we went into the theater to see that film, our hopes about to be crushed like an empty soda can rolling onto a busy freeway. Why wasn’t this a problem? We were going to find out WHY Darth Vader turned to the Dark Side. WHERE he began. HOW he learned to use his Jedi powers. WHO taught him how to sound more like a robot than R2-D2 when talking to a woman. The Star Wars prequels and “Nemecia” have at least one thing in common: both are stories that emphasize the journeys undertaken by the characters, not their ultimate destinations.

What Should We Steal?

- Employ an object as the entry point of your story. While it’s possible to do so in a clunky manner, it’s perfectly natural, for example, for a first-person narrator to tell a story about the grandfather who owned the fountain pen he’s holding.

- Maintain focus on the truth of your character, not the boring details. Whatever. Jean Valjean dies at the end of Les Miserables. The death itself doesn’t matter; We (and Hugo) care about what Valjean accomplished with his life.

Short Story

2012, Best American 2013, Kirstin Valdez Quade, Narrative Magazine, Objects