Title of Work and its Form: Looking for Alaska, novel

Author: John Green (on Twitter @realjohngreen)

Date of Work: 2005

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book can be purchased at all fine bookstores.

Bonuses: Mr. Green and his brother Hank are prolific makers of videos; these short films confront a wide range of subjects and are a lot of fun. Find the “vlogbrothers” at their YouTube page. Mr. Green answers a number of questions about Looking for Alaska on his site. (The answers are very intelligent and generous.) You should also know about Mr. Green’s tumblr page. Mr. Green’s work has inspired a lot of very cool young people to do very cool things. Look at this incredible (and pretend) trailer that some folks made for a hypothetical film adaptation of the book:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Miles is a bright young man who is seeking education and enlightenment. This search leads him to leave his Florida home for Culver Creek Boarding School, a place with rigorous educational standards and a lot of brilliant students. The Culver Creek student body is very diverse, especially in terms of socioeconomic status. Miles’s new roommate Chip (The Colonel) is very poor, but some of his classmates are delivered to school by limousine. Whattaya know, Miles meets Alaska, an incredibly beautiful, smart and troubled young woman. Miles joins his new circle of friends in their adventures; he gets in a little bit of trouble and learns an awful lot in his first year in boarding school.

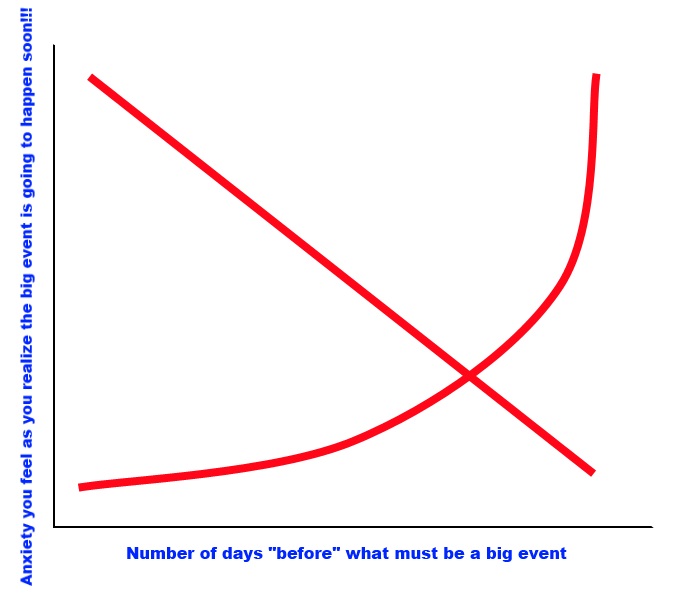

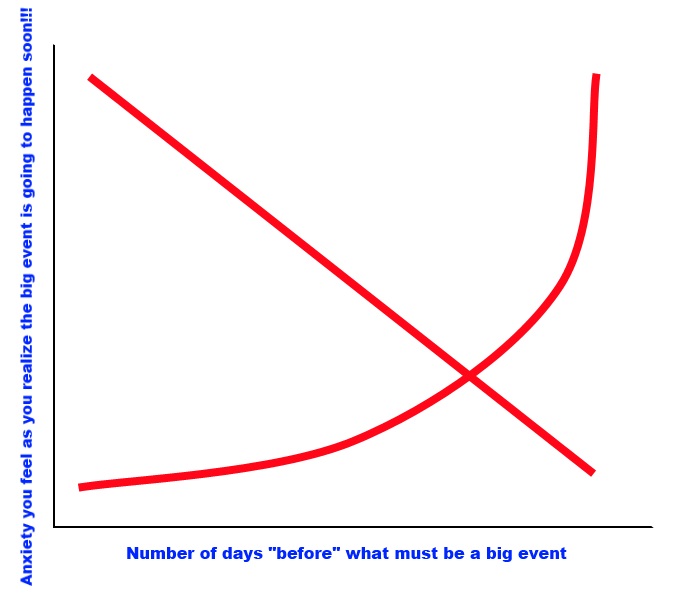

The book has a structure worth discussing. There is a big event that takes place halfway through the book. Each short chapter is labeled to indicate how many days BEFORE or AFTER that event the chapter takes place. Mr. Green has chosen a felicitous way to imbue that big event with importance: A COUNTDOWN. Imagine you’re sitting down to read the book for the first time. You start reading and discover that the first little chapter is taking place “one hundred thirty-six days before.” You’re wondering, “before what?” Before long, Miles/Pudge meets Alaska and the Colonel and Takumi and Lara and that number keeps decreasing. Things are going so well! Miles is learning a lot about life…he’s having a good time with friends…he’s breaking the rules a little bit by drinking and staying up late, but he’s not doing anything TOO crazy…what could go wrong? As the number of days before the big event dwindles, our anxiety increases exponentially. Why? The events are getting bigger. Miles and his friends are planning a big prank and he’s getting closer to Alaska, which is what he wanted all along. Here’s a graphical representation of how we’re feeling as we read:

How does Mr. Green amp up the drama so much? He uses that COUNTDOWN. Dramatists love the countdown because it makes an explicit promise that SOMETHING INTERESTING IS GOING TO HAPPEN. What are some other cool countdowns? The Apollo missions resulted in men walking on the Moon. How did those missions kick off? A countdown, of course. Those decreasing numbers make a promise: once we’re down to zero, there’s going to be a massive and beautiful explosion that (hopefully) propels the spaceship into orbit.

What do we all do on December 31? We sit around the TV and wait until that countdown.

Again, there’s an implied promise. After we get down to zero, there’s going to be a new year ahead of us, one filled with hard work and good fortune. (One hopes.)

The countdown feels right because it’s natural. Each of us spent, give or take, nine months in the womb. Our parents were counting down to the moment we were to arrive. Mr. Green borrows the power of the countdown to make us anticipate the big event that changes the characters; the suspense we feel boosts its power and meaning.

I’m writing a likely-never-to-be published Young Adult novel, so I’ve been reading a bunch of them. (Makes sense, doesn’t it?) I grew up reading books by great writers such as Judy Blume and Bruce Coville. What’s just one thing that Mr. Green has in common with these two? They treat young adults, well, like adults. It has been a few years since I was a young adult myself, but boy, do I remember Teenage Ken and what was happening around him. While I did not drink underage (not that I want a medal), I was somewhat aware that it was happening around me. Some of my classmates were doing drugs, legal and otherwise. Many of them were having sex and most of them really wanted to. Mr. Green allows his young adult characters to act, talk and think in a manner that is realistic for young adults. It took a few pages, but I was happy to see the first “naughty” word in the book. I love that Miles falls quickly and deeply in love with Alaska because that’s exactly what young adults do. (And Alaska was totally my thing when I was seventeen: smart, fun, pretty and damaged enough to understand my damage? I wouldn’t have been able to resist falling in love with her!)

As I expected, Looking for Alaska has been challenged by parents and administrators. Why is this crazypantslooneycounterproductivetosociety? A story that doesn’t feel real is not going to affect the reader. A great work must somehow create the appearance of reality in fiction. This is a concept called verisimilitude. Let’s say you’re late to work. Your boss asks you why you are late and you tell him or her:

It was the craziest thing. I was driving here-on time, I might add-when I saw this bright light ahead of me. It was an alien spaceship. All of a sudden, I was on board and they were doing all of these funny experiments on me. But it wasn’t all bad; they took me out to Pluto and showed me mountains made of diamonds and let me watch a game of Space Baseball before they zapped me back into my car.

The boss is not going to believe your story. Why? Because it does not have the appearance of reality. Nor does a story focused upon dozens of teenagers that is devoid of drinking, smoking, sex, defiance of authority, staying up late and lying to parents.

No, friends, being late to work requires you to come up with a story with much more verisimilitude. So, you were late to work because you overslept. But you don’t want to come out and TELL YOUR BOSS you have trouble getting up on time. What cover story can you tell that FEELS real?

Hey, I’m so sorry. One of my tires was really flat and I simply couldn’t get here without taking the time to fill it up a little.

See? Makes sense. Realistic. It happens every day. (It happened to me not too long ago.) Above all, it’s our job to serve the reader, not to write books according to the desires of people who aren’t going to want to read the work anyway.

Miles/Pudge and his friends have a nemesis, of course. The Eagle is the dean of students. He sees everything that goes on and doles out punishments accordingly. The characters (quite appropriately) see him as something of an out of touch and needlessly authoritarian figure. After all, he busts them for smoking, sends them to Jury and spends his days trying to ruin their fun. And there is a big threat; he already expelled two people last year for three big Culver Creek sins.

When you’re young, it’s tempting to think of authority figures as something other than a real person. As a robot who only serves a function. Ever see Police Academy? If not, you should. Captain Harris is (pretty much) an authoritarian jerk who just wants to make life hard for the protagonists/heroes of the film. See?

Dean Wormer from Animal House-seriously, go watch that one right now if you haven’t seen it-is primarily a one-dimensional jerkface.

I grew to love The Eagle because Mr. Green slowly builds him into a real character. In the beginning of the novel, of course, The Eagle must be a jerk. He needs to lay down the law. He can’t show any soft underbelly because he needs to be seen as an authority figure.

Maybe it’s just because my own YA years look so small in my rear view mirror, but I identified with The Eagle a little bit. He’s not TOO MUCH of a jerk. More importantly, he’s not mindless or heartless. He knows that you have to let young people get away with a little bit. Adolescence is about learning how far you can bend the rules without breaking them and ending up in REAL trouble.

102 days “after,” the main characters play a prank on the school. I don’t want to ruin anything, but it’s a good kind of prank: no one gets hurt, no property gets damaged. The Eagle knows darn well that Pudge, et. al. are responsible for the prank. Does he expel them? Does he punish them? No. He knows that adding to their grief would be counterproductive and that the prank is part of the process by which they are recovering by the book’s big event.

Characters (usually) shouldn’t be all good or all bad. The Eagle is an immovable authority figure/narrative obstacle most of the time, but Mr. Green very wisely gives him a couple moments that reveal his deep humanity. Mr. Green is in great company. Another writer who refused to turn his law enforcement officer into a one-dimensional cartoon character was Victor Hugo. We love Javert (from Les Miserables, obviously) because the events of the book change him and reveal the very human struggle inside him.

What Should We Steal?

- Recognize the natural countdowns around us and use them in your work. If you’re in the Northeast, Winter will give way to Spring. Sure, there may be two feet of snow on the ground and the temperature may be in the single digits…but that is going to change at some point.

- Respect your audience by giving your work verisimilitude. Readers won’t like your work unless your fictional piece offers the appearance of reality.

- Imbue all of your characters with humanity and give them a moment or two in which they can express it. The best heroes have flaws and the scariest villains have virtues.

Novel

2005, John Green, Looking for Alaska, Narrative Structure, Young Adult

Title of Work and its Form: Twilight, novel

Author: Stephenie Meyer

Date of Work: 2005

Where the Work Can Be Found: You can find the book just about anywhere.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Sentence-Level Issues

Discussion:

Full disclosure: I am not in the target demographic for Twilight and the story and writing don’t particularly do much for me. The worse angels of my nature sometimes whisper in my ear that I should blast books and pieces I don’t feel are particularly good. I learned indirectly that this was the wrong way of thinking from Mrs. Iodice, my AP English teacher. She had us read Jane Eyre, a book that didn’t particularly appeal to me. Should I dismiss such a classic out of hand? Of course not. Even though Jane Eyre isn’t my favorite book, it’s a far more beneficial policy to learn from it than to deride it. The same principle applies to Twilight. Millions of people bought the book and people enjoyed the book, so why not investigate what Ms. Meyer’s book has to teach us?

Create characters and situations that appeal to your target audience.

I know very little about women of any age, but Bella certainly seems like a fairly representative teenage girl. As many cultural critics have pointed out, the book appeals to a young woman’s fear of and desire for sex. Becoming a vampire and losing one’s virginity changes a person into something else. There are severe consequences for those who “turn,” including loss of social status, pregnancy and disease. I’ll happily wager that Twilight has helped countless young people work out their feelings about their sexuality. Ms. Meyer has found great success appealing to these very common psychological dilemmas.

Tread a new path through an old mythology.

Dangerous mythological creatures one sort or another have been with us for just about forever. Vampire conventions have changed over the decades. Ms. Meyer has put her own spin on them. Her vampires sparkle and play baseball and have extensive families. While the publishing market will fluctuate for each kind of creature (vampires may be cold now, but werewolves are hot), there will likely always be an audience for well-written books that take a new look at classic sources of terror.

Okay, with that said, let’s look at some specific sentence-level issues from Twilight that writers must consider in their work.

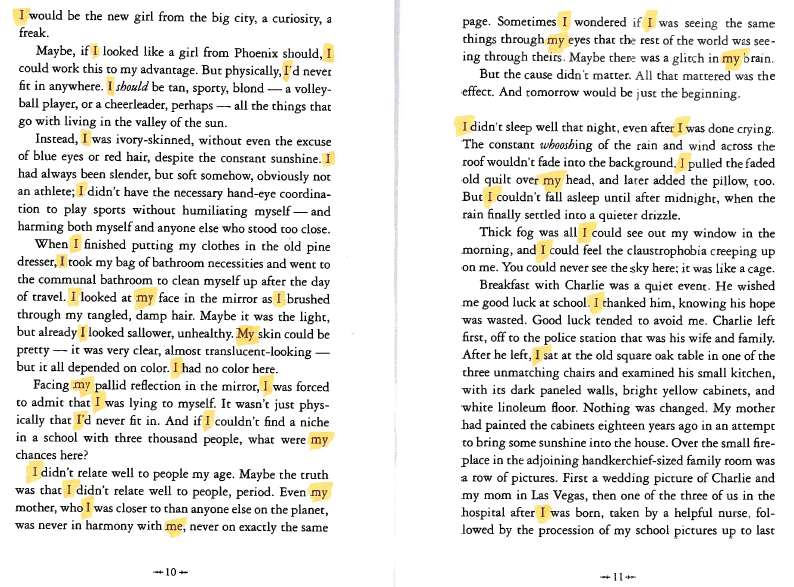

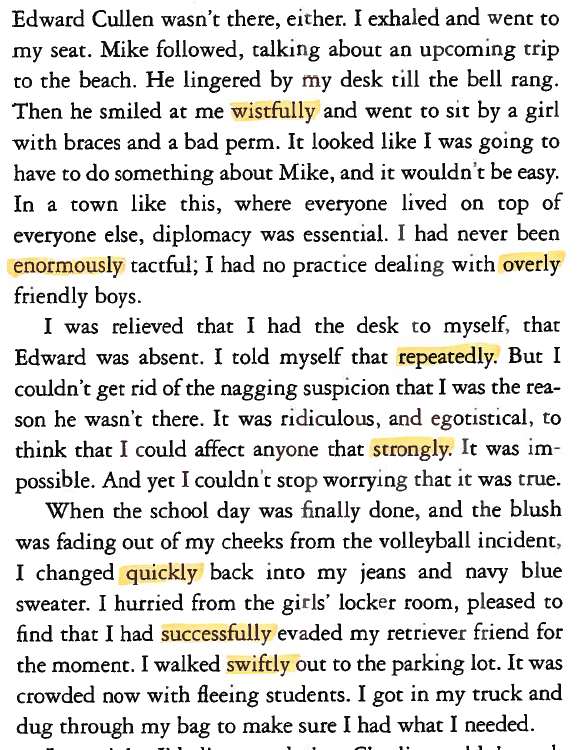

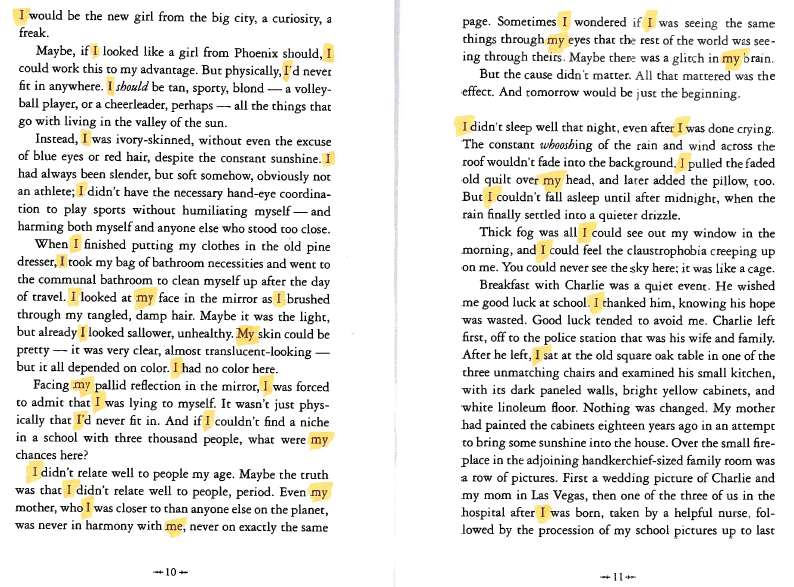

Avoid the overuse of “I.”

If you are writing in the first person, you’re probably going to use “I” and “me” a great deal. The use of the word is sometimes unavoidable. The problem is that the overuse of the word can result in repetitive and lifeless paragraphs. What is the solution? Recast as many sentences as you can without “I.”

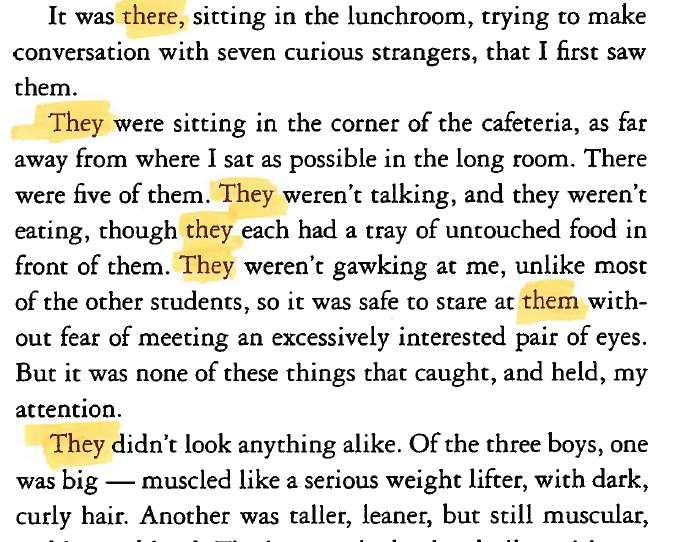

Replace words such as “they” and “there” and “things” with more descriptive terms.

“They” is a very valuable pronoun; the word allows the writer to characterize a group or to describe their actions with great efficiency. Unfortunately, each time you use “they,” you’re missing an opportunity for characterization or detail. Look at the above example. Instead of writing “they,” Ms. Meyers could have taken advantage of the chance to lend more specificity to the work. Here are some examples of what she could have used to replace a “they” or two:

“They” is a very valuable pronoun; the word allows the writer to characterize a group or to describe their actions with great efficiency. Unfortunately, each time you use “they,” you’re missing an opportunity for characterization or detail. Look at the above example. Instead of writing “they,” Ms. Meyers could have taken advantage of the chance to lend more specificity to the work. Here are some examples of what she could have used to replace a “they” or two:

- The creepy vampire family

- The pale people at the table

- Those darn Cullens

- Everyone’s favorite outcasts

Are all of these appropriate? No. But see how these phrases add a lot more to the story than “they?”

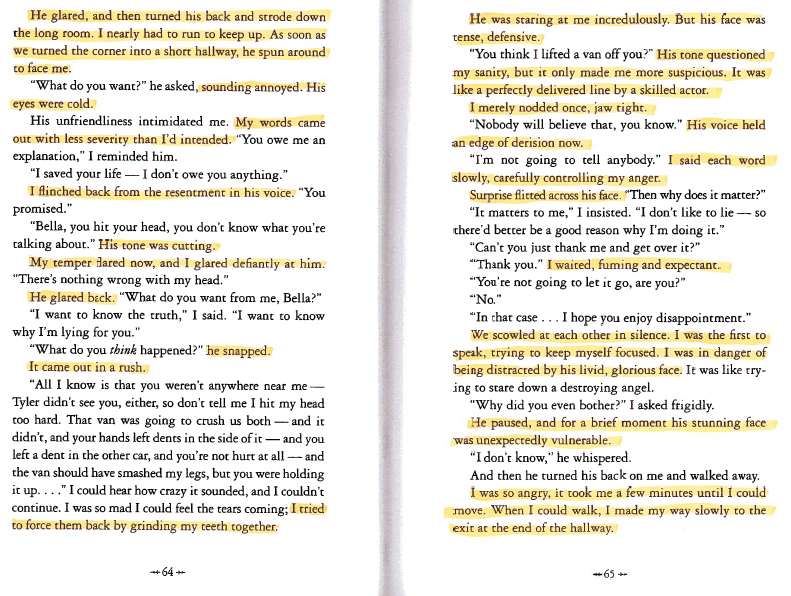

Ignore the need to over-choreograph a scene.

Ms. Meyer offers an awful lot of minute detail for each facial expression her characters make. She could have focused on the important ones, leaving the reader to provide the rest. Think of it this way. What’s wrong with this bit of dialogue?

Ms. Meyer offers an awful lot of minute detail for each facial expression her characters make. She could have focused on the important ones, leaving the reader to provide the rest. Think of it this way. What’s wrong with this bit of dialogue?

“I’m going to kill you, jerk!” He said with anger.

Anger is the expected tone one would use to threaten someone else. You only need to specify the tone of the expression if, for example, the character were joking.

The great Lee K. Abbott would also point out another bit of over-choreography. Ms. Meyer writes, “We scowled at each other in silence. I was the first to speak…” Ms. Meyer did not need to have Bella tell us that she and Edward scowled in silence. How do we know they were silent? There was no dialogue. Further, we know that Bella is the first to speak because she has the first subsequent line. Just as Strunk & White advise us to “omit needless words,” we must also omit needless description.

Restrict your use of adverbs.

Remember: adverbs are shortcuts and are often superfluous. Is the word “successfully” necessary in this example? How about saying that Bella “dashed” instead of “walked swiftly?”

Remember: adverbs are shortcuts and are often superfluous. Is the word “successfully” necessary in this example? How about saying that Bella “dashed” instead of “walked swiftly?”

Novel

2005, Sentence-Level Issues, Sparkly Vampires, Stephenie Meyer, Twilight

Title of Work and its Form: The Language of Baklava, creative nonfiction

Author: Diana Abu-Jaber (on Twitter @dabujaber)

Date of Work: 2005

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book was released in hardcover and paperback. You can purchase it online or at your favorite local bookstore. If you live in Oswego, New York, consider buying the book from The River’s End.

Bonuses: Here is a very sweet interview in which Ms. Abu-Jaber discusses cooking for children. Here is a 2004 interview that is very interesting in spite of its age. Here is a Washington Post review of her most recent novel, Birds of Paradise.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Ms. Abu-Jaber’s book is a particularly pure example of one of the primary uses of literature. As you read The Language of Baklava, you learn all about Jordanian culture and how a second-generation Jordanian American reconciles the two traditions in her own life. More importantly, this kind of literature teaches us that we’re all pretty much the same, no matter where we grew up. Ms. Abu-Jaber tells the story of her childhood in a chronological manner, from the time she was approximately six through her adulthood. Ms. Abu-Jaber spends a great deal of time introducing you to her close relatives and extended family and even describes her own experience living in Jordan. The book is not jam-packed with extreme experiences or heartbreaking trauma. Instead, Ms. Abu-Jaber weaves a comforting tapestry of memory and emotion that truly add up to a meaningful expression of her identity.

The book and its author hold a special place in my heart. Ms. Abu-Jaber attended Oswego State University…just like I did! (Am I the only one who admires the successful writers in whose footsteps I hope to follow?) When I was in grad school, The Language of Baklava was chosen as the Ohio State freshman book, so I had the pleasure of leading a brief discussion with some randomly chosen young people who read the book. While I got the occasional thrill out of recognizing some of the places described in Baklava, you certainly don’t need to know the Central New York area in order to enjoy the book.

Ms. Abu-Jaber begins the book in a felicitous manner. When she was a small child, Ms. Abu-Jaber sat in the audience of The Baron Daemon Show, a local children’s show that aired on Channel 9 in Syracuse. (I happen to have grown up in the Syracuse area, but slightly later than Ms. Abu-Jaber did.) These kinds of programs once dominated Saturday mornings across the country. A local host—a vampire, a clown, a railroad conductor—would entertain a live studio audience of children and kids across the viewing area would join in on the fun from their living rooms. The hosts, of course, would interact with the children in the studio. Well, Baron Daemon (portayed by newsman Mike Price) greeted the children in the audience. Immediately deciding the proper pronunciation of the name was easy for the host when the children were named Bobby Smith or Debbie Anderson. Then the Baron got to Ms. Abu-Jaber and her family: “Farouq, Ibtissam, Jaipur, Matussem.” Upon seeing “Diana” on the name tag, the Baron must have felt relief. Then he “crashed” into Ms. Abu-Jaber’s last name. Not surprisingly, the Baron chose to speak to the author: “Now Diana, tell me, what kind of a last name is that?” Ms. Abu-Jaber laughed as she shouted, “English, you silly!” The one-page anecdote establishes the tone of the book. Ms. Abu-Jaber and her family were and are both American and something else. The host of the show certainly didn’t mean any offense in being unable to work through the Jordanian names, but the incident, especially in retrospect, is a reminder that cultural identity is not as simple a thing as we might think.

Here is the Baron in action, in case you’re curious:

So the opening scene introduces the theme in an entertaining manner. Immediately thereafter, Ms. Abu-Jaber tells the scene of a family picnic in a Central New York park. The reader meets all of the characters and learns about the food, the family conflicts (both internal and external) and allows Ms. Abu-Jaber to insert the first of several recipes that form the backbone of the book’s structure. In the space of a few pages, the author has immersed the reader in the world of Jordanian Americans and in that of her family. (If only it were that easy to be comfortable when you meet a significant other’s family!)

When I first read the book, it didn’t take me long to realize that Ms. Abu-Jaber, well, she is the protagonist of the book and she isn’t. By necessity, this memoir is structured around her memories and her life, but I love that the author, at times, allows herself to be a part of the ensemble instead of the star. This seems like a strange thought, doesn’t it? If you pick up Amanda Knox’s memoir, you darn well better read about how she was arrested for murder in Italy, right? She better be the focal character. Baklava is about family and culture, both institutions that are focused on the intersection between the individual and the whole, so it makes sense to modulate the importance of the author in the narrative.

Let’s talk about those recipes. Each chapter features at least one recipe drawn from Ms. Abu-Jaber’s life. When we experiment with form, we must ask ourselves whether we are serving the overall story. Shouldn’t this be our top priority? While the reader may not rush out to Wegmans to pick up all of the ingredients, the recipes in the book certainly do contribute to the narrative. Food is a fascinating element of culture; people all over the world have pretty much the same ideas about food, but the little differences in climate and population and so on have resulted in culinary diversity. (Every culture has something resembling a dumpling. Every culture combines sweet and savory in different ways.) Ms. Abu-Jaber also ensures that the recipes have a meaningful purpose. For example, Chapter Seven begins with a family party and lots of people are on their way. Therefore, Ms. Abu-Jaber introduces the reader to “Start the Party” hummus, the same food that is likely being prepared in the kitchen. (It’s also interesting to think about hummus as an “ethnic” food; is it just me, or has that changed over the past couple decades? Remember, dear reader, that spaghetti was once considered an “ethnic” food and is now as American as apple pie. Which I suppose is pretty much a tart, the likes of which have been made in Europe for centuries. See how the recipes in the book relate so heavily to its theme?)

What Should We Steal?

- Immerse your reader in your unique world as quickly as you can. Ms. Abu-Jaber hits you with an anecdote that relates to theme (a person straddling two cultures) and introduces the vast cast of characters…all in the first dozen pages.

- Allow yourself to take the back seat, even in your own story. Depending on the scene, you may wonder: is this YOUR STORY, or a story ABOUT YOU?

- Augment stories with tangential elements if they will help you accomplish your goals. Storybooks have pictures for a reason, not just because the pictures are pretty. They make it easier for the young reader to understand the story. Business biographies often have sections filled with photographs. These are not only fun, but they can help you keep the “characters” straight in your head.

Creative Nonfiction

2005, Baklava, Diana Abu-Jaber, Narrative Structure, Oswego State

Title of Work and its Form: “Best New Horror,” short story

Author: Joe Hill, on Twitter at @joe_hill

Date of Work: 2005

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was first published in Issue 3 of Postscripts, a journal published by the UK’s PS Publishing. Mr. Hill subsequently chose to lead his first short story collection 20th Century Ghosts with the piece.

Bonuses: Here’s what Terrence Rafferty of the New York Times Sunday Book Review thought of Mr. Hill’s work. (Long story short: he liked it.) And here’s Graham Sleight’s thoughtful review of the collection and its lead story.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Acceptance of Genre Work

Discussion:

Eddie Carroll is the editor of Best New Horror, a yearly anthology of stories that represent the best in the genre. Eddie is in something of a lull in his life—his wife is gone and he hasn’t been really excited about any new stories—when he is sent a copy of “Buttonboy.” It’s a nasty little story about a random act of extreme violence that determines (and becomes) a woman’s fate. The story is controversial and unpleasant and the ending is fairly predictable, but Eddie wants to publish it. The author, Peter Kilrue, is a difficult man to find. Eventually, Eddie does find him. The ending of “Best New Horror” is controversial and fairly predictable. (What can I say? I liked it.) I need to ruin the ending in order to discuss the points I had in mind, so here be spoilers: Eddie tracks Peter down in the middle of nowhere; Peter Kilrue’s mailbox decals have flaked away and they now read “KIL U.” And that may be what happens to Eddie, who heads into Creepy House and quickly realizes that Kilrue is the kind of artist who WRITES WHAT HE KNOWS. The creaky house is filled with weird people who like to chop what looks like liver when shirtless and who like to tie old women to beds with wire. Eddie runs to his car, careful not to twist an ankle: “He had seen it happen in a hundred horror movies.” Eddie remembers that his keys were in the jacket he gave to one of the Creepies. The reader leaves him as Eddie is running away. If anyone can elude homicidal maniacs, shouldn’t it be the guy who spends all of his time reading about them?

Mr. Hill is known primarily as a horror writer, but he seemingly refuses to be stifled by any artificial constraints. Some people, after all, say “science fiction writer” or “romance writer” with a disappointed snarl. Why must a genre classification be perceived as an indication of quality? “The Lottery” and “The Yellow Wallpaper” are rockin’ stories…and they could be considered psychological horror. “The Cold Equations” and Fahrenheit 451 are punch-to-the-gut narratives…even though they’re science fiction. A third of the way through “Best New Horror,” Eddie Carroll editorializes about this sad perception of genre:

Among the cognoscenti, though, a surprise ending (no matter how well executed) was the mark of childish, commercial fiction and bad TV. The readers of The True North Review were, he imagined, middle-aged academics, people who taught Grendel and Ezra Pound and who dreamed heartbreaking dreams about someday selling a poem to The New Yorker.

The conventions of craft are simply tools. Even if you are writing a “literary” story, you would do well to borrow the tools of “horror” writers. (Can you name any writers who are better at ratcheting up the tension in a narrative?) Science fiction is a genre about examining new ideas and new technologies and deciding how they fit into ever-changing concepts of humanity. Writers of “literary” fiction should definitely understand how folks like Ray Bradbury and Harlan Ellison view the world and the people on it. I must confess that I have spent a lot of time thinking about this enforced dilemma. Science fiction was my first love growing up and it has always bothered me when folks dismissed a book or a writer because they worked in a genre of some kind. Stephen King is a top-flight writer, as capable with literary fiction as white-knuckle horror. I read Diff’rent Seasons and The Bachman Books when I was really young and grew up protesting those who said Mr. King was only a vampires-and-women-with-telekinetic-powers kind of guy. (A lot of my students don’t realize that Stand By Me, The Shawshank Redemption and It emerged from the same fertile mind.) I’ll put the aforementioned Harlan Ellison and Ray Bradbury up against any poet with respect to their ability to create beautiful sentences.

Here’s a little chart that elucidates what different genres can teach us about writing craft:

|

Genre

|

What Writers in the Genre Can Teach Us

|

| Action/Adventure |

The creation of compelling protagonists, descriptions of interesting action setpieces |

| Crime |

Simple but extremely descriptive language, an understanding of the fringes of the “real world” |

| Fantasy |

The depiction of elaborate worlds that are realistic and unrealistic at the same time |

| Horror |

How characters feel and act when they are in the greatest physical danger of their lives |

| Mystery/Detective |

The exploration of deviant psychology, the ramifications of violations of the social order |

| Romance |

What brings lovers together and what separates them |

| Science Fiction |

How humanity adapts and changes to ever-changing technology (or how it remains the same) |

| Western |

What it is like to occupy virgin territory, how to write characters who are alone quite a bit |

“Best New Horror” also brings to mind two non-horror works: the Stephen King novella “The Body” and John Irving’s novel The World According to Garp. Two points if you can guess what these three pieces have in common. All three contain framed narrative. In “Best New Horror,” Mr. Hill extensively summarizes “Buttonboy.” Mr. King allows Gordie Lachance to tell the story of Lard Ass. Mr. Irving’s book includes “The Pension Grillparzer,” the title character’s first novella. Including such a framed narrative is a risk. I’ll admit that I skipped “Grillparzer” the when I read Garp as a fourteen-year-old. Why? Because Mr. Irving was telling such a great story about such an interesting young man…and then he assigned me to read dozens of pages of a different story in a different font. (No worries; I’ve long seen the error of my ways in that regard.) I didn’t mind Lard Ass story in “The Body” because it fit into the story; what do teenage guys do around a fire but tell dirty or weird stories?

Mr. Hill, no doubt, knew that he HAD to tell the reader a lot of details about “Buttonboy.” The story, after all, reflects upon Kilrue’s psychology and sets the protagonist into action. Mr. Hill doesn’t waste your time; he describes the plot of “Buttonboy” in sentences that are at once short and declarative and chilling. Our framed narratives should serve as an imperative part of our story; they shouldn’t seem like an accessory.

What Should We Steal?

- Wear your genre badges proudly. Successful genre writers are really demonstrating that they have exceptional skills in at least one facet of storytelling. Romance writers, for example, have extreme insight into what people want to believe about love. When last we see Mr. Hill’s narrator, he’s running for his life, buffeted by the knowledge he gleaned from all the stories he read about characters in the same situation. Mr. Hill, it seems, is saying that understanding genre writing can save your life.

- Ensure that your framed narratives work in the context of the bigger story. Go right ahead: show your reader a poem that your character “wrote.” Just make sure that you’re not holding up the procession of your larger narrative.

Short Story

2005, Acceptance of Genre Work, Genre, Joe Hill, Postscripts

Title of Work and its Form: “Baby Got Back,” pop song

Author: Music by Jonathan Coulton, Lyrics by Anthony Ray (better known a Sir Mix-a-Lot)

Date of Work: The original version of the song was released in 1992 and Coulton’s cover dates to 2005.

Where the Work Can Be Found: The original was originally released on Sir Mix-A-Lot’s hit album Mack Daddy. Coulton’s reimagining of the song was originally released on his album Thing-a-Week One. You can purchase the song from Amazon here.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Appropriation

Discussion:

All creative people steal. We just do. The point is that we must steal in the proper way while respecting the rights of other artists. I suppose the question that you must ask yourself when you’re stealing is the following:

AM I ACTUALLY BEING CREATIVE OR AM I JUST CUT-AND-PASTING?

Johann Sebastian Bach, one of the all-time great composers, wrote this “Minuet in G Major.” Check out the melody:

“A Lover’s Concerto” was written by Sandy Linzer and Denny Randell and was first recorded by The Toys in 1965. Compare the melody of the Bach to that of “Concerto.”

They’re practically the same, aren’t they? Why shouldn’t we be angry at Linzer and Randell?

- Bach had been dead for two hundred years when they stole his work.

- Public domain laws allow you to do whatever you like with old creative work because they are considered the property of the people, of American culture.

- Linzer and Randell completely transformed a simple (but beautiful) piano/harpsichord composition into a full-blown pop song. They took the opening melody of the minuet and added lyrics and did a whole lot of creative work.

Okay, let’s look at another case of theft.

In 1992, Sir Mix-a-Lot got everyone bumping with his ode to behinds, “Baby Got Back.” The song can be heard everywhere, from dance clubs to junior high school dances. Go ahead. Listen to the original and feel free to dance as though no one is watching.

Did Sir Mix-a-Lot know he would change the world with his song? No. Fourteen years later, independent musician Jonathan Coulton decided he wanted to do a cover of “Baby Got Back.” He paid Sir Mix-a-Lot for a license to re-record his song. Why? Because Sir Mix-a-Lot worked really hard to write “Baby Got Back.” Coulton didn’t want to claim someone else’s creative work as his own. Further, Coulton credited Sir Mix-a-Lot for his lyrics each time the song has been released.

Here is Mr. Coulton’s “Baby Got Back,” released on a Creative Commons license. (Well, I’m not a lawyer, but I believe it means that Mr. Coulton is not mad at you if you share the music with others as long as you don’t CHARGE THEM MONEY or FAIL TO CREDIT THE SONG TO HIM.)

What are the differences between Coulton’s “Baby Got Back” and Sir Mix-a-Lot’s?

- The choral opening: “L.A. face with the Oakland booty.”

- The banjo arpeggio under the verses.

- The entirely new melody for the lyrics

- An interpolation of a new lyric: “Johnny C’s in trouble.”

- The creation of an entirely new choral arrangement for the bridge

- The use of a duck quack to replace the word “fuck.”

Okay, now listen to the version of “Baby Got Back” that was released by Twentieth Century Fox as part of its television show Glee. (A program dedicated to glorifying the beauty of creativity and to pointing out the great emotional cost of bullying.)

Yeah, so what did you hear? It’s the same song, isn’t it? In the weeks after the Glee version was released, Twentieth Century Fox didn’t credit or pay Coulton for his work. Is this bad stealing? I would say so. Either they used his actual instrumental track or they recreated it PERFECTLY. The only creative work that Glee did was cue up the karaoke version of Coulton’s song and have the kids sing (into Autotune). Whether or not you like any version of the song, it’s clear that Sir Mix-a-Lot and Mr. Coulton both put a lot of creative energy into the music they created. Sir Mix-a-Lot created the world’s most popular tribute to the female derriere and Mr. Coulton completely reimagined the song. Glee opened up a mic, clicked “record” and collected tons of money.

In case you’re not convinced, here’s a comparison between the two. The Coulton version comes out of one speaker and the Glee version comes out of the other.

What Should We Steal?

- Give credit where credit is due. We all steal, so we shouldn’t be embarrassed about acknowledging it. If you steal a poem format from another writer (but you honestly wrote the poem), maybe you will precede your poem with “After Liz Lemon.” (Or whatever the writer’s name is.)

- Understand the fair use doctrine. United States Copyright Law allows you to take different amounts of different works at different times. I, for example, feel perfectly comfortable quoting a paragraph of a short story. Why? Because I’m “stealing” a very small piece of a work in the interest of scholarly criticism. The law is on my side. The law would NOT be on my side if I erased the first line of a friend’s poem and I made a new one and slapped my name atop the page.

Song

1992, 2005, Appropriation, Baby Got Back, Glee, Jonathan Coulton, Sir Mix-a-Lot

Title of Work and its Form: “Gravity,” short story

Author: Lee K. Abbott

Date of Work: 2005

Where the Work Can Be Found: “Gravity” was first published in the Fall 2005 issue of the Georgia Review. The story was included in All Things, All at Once, an anthology of new and selected stories by Mr. Abbott. The book is great and makes a thoughtful present for anyone who knows how to read. Or anyone who likes pictures of desert roadways and serif fonts.

Bonus: Wow, here’s an interview Lee did with The Atlantic. And here’s one he did with William H. Coles!

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Suspense

Discussion:

“Gravity” takes you in from its first sentence: “They grab her—Tanya, my fourteen year-old daughter—early in the afternoon from the sidewalk outside the north entrance to J.C. Penney’s at the Mimbres Valley Mall.” Poor Lonnie Nees, the first-person narrator, copes with the truth of his daughter’s disappearance and the fact that he really didn’t know the young woman he loves so much. There’s a lot to do; he must meet with the police, call his ex-wife and search the girl’s bedroom. What happened to Tanya? It’s not a spoiler, as Lee tells you early on that the young woman simply ran away, as young people sometimes do. What is the point of the rest of the story if we already know that Tanya is (probably) alive and (somewhat) well?

Friend, this all ties into what we’re going to steal. Why does Lee tell you the outcome of the story 15% of the way into the narrative? Because his idea was not to tell a crime story. The disappearance itself is not the point. No, Lee cares far more about the emotional impact of the disappearance on Lonnie and his ex-wife and his girlfriend and everyone else in the community. What will the grieving father think when he learns what his precious little girl has been doing? What will he do to the young man who may know where she has gone? What effect will the disappearance have on her parents, former lovers who have parted, but will always have Tanya in common? Aren’t these questions much more captivating than “Hey, where’s Tanya?”

The story is also compelling because Lee adheres so closely to Freytag’s dramatic pyramid. Gustav Freytag was a nineteenth-century writer and critic who studied Greek drama and isolated what makes a story great. Here’s a graphic representation that adds some modern refinements to Freytag’s ideas:

Look how “Gravity” fits into the structure:

Look how “Gravity” fits into the structure:

Exposition (establishing the story’s situation and characters)

- In the first sentence, we learn the narrator is Lonnie Nees, the father of a young woman and lives in southwestern New Mexico.

Inciting Incident (the event that kicks off the story’s path)

- Tanya, the daughter, has been “grabbed.”

Rising Action/Complications (the protagonist experiences obstacles and the situation increases in intensity)

- Lonnie gets “the call” from the sheriff.

- Lonnie tells his ex-wife about their daughter being in danger.

- The sheriff looks around Tanya’s room and finds drugs.

- Lonnie looks through…unpleasant…photos Tanya had in her locker in hopes of helping the police. Tanya has been up to some…stuff that Lonnie didn’t know about.

- Lonnie gets a phone call that may be from someone who knows Tanya’s whereabouts.

- Lonnie heads to the dump to meet the Sheriff; they’ve found objects that may belong to Tanya.

Climax (the highest point of tension, after which nothing is the same)

- Lonnie visits the gang leader who has “interfered” with Tanya. Lonnie threatens him with a gun and comes awfully close to using the weapon for reasons any father would understand.

Denouement/Falling Action (life settles into its new normal as the characters deal with the events of the story)

- The consensus is that Tanya is in Los Angeles; the Sheriff takes the gun and Lonnie understands that his new life, for the time being, will not involve his daughter.

See? The story just FEELS right because of the way that Lee tells it. I’m not saying that writing must be formulaic; there’s just a natural, organic procession to the events that feels like real life.

What Should We Steal?

- Create the most appropriate kind of suspense for your story. You are certainly welcome to write a killer thriller story about the disappearance of a child, but that requires a different focus. You will likely include far more scenes about the mechanics involved in getting a kid back home.

- Pay homage to Freytag. Screenplays tend to follow the Syd Field formula very closely. (This structure borrows a lot from Freytag.) While you shouldn’t struggle to put your inciting incident on page 1 and one complication every other page and a climax on page 15, you should consider the flow of your story with respect to Freytag’s thoughts.

Short Story

2005, Lee K. Abbott, Ohio State, Suspense, The Georgia Review

Title of Work and its Form: “Charlie Got Molested,” an episode of the television program It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia

Author: Written by Rob McElhenney, directed by John Fortenberry

Date of Work: Originally aired September 15, 2005

Where the Work Can Be Found: There are DVD sets for each season of the show and the episode is currently streaming on Netflix.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Characterization

Discussion:

It’s Always Sunny is not a show for the faint of heart. It is, however, produced by people who clearly love the sitcom and wish to put their own spin on the art form. The conceit of the show is relatively simple: four (later five) narcissistic friends who own a bar in Philly stumble through life, creating one uncomfortable situation after another. While the creators of the show are human beings with empathy and sympathy, the characters do not.

The episode begins as the friends learn that their former gym teacher has been accused of molesting students. Upon hearing the news, Charlie becomes evasive and leaves the bar in a huff. There’s only one conclusion: “Charlie got molested.” Instead of considering how to help Charlie, the remaining three friends debate the exact kind of molestation that happened and Mac is even clearly offended that the teacher didn’t try anything with him. Charlie seeks out the “gross” McPoyle brothers, the young men who are accusing the teacher. The McPoyle brothers reveal that they know they were not molested, but are making the accusations in hopes of “making millions.” Charlie is blackmailed; if he denies also being molested, then the McPoyles will tell the police the scheme was his idea…which it was. (Charlie was drunk; no surprise there.) Mac goes to the teacher’s home and tries to seduce Coach Murray, attempting to understand why the man never went after him. The blackmail forces Charlie to tell his mother that he was molested. During a trip to the police to lodge a complaint of his own, Charlie rats out the McPoyles. To some extent, life is back to normal.

The program is notable because the characters are so unlikeable. On most television shows and in most movies, the writers clearly want the characters to be relatable heroes. Instead, the denizens of Paddy’s Pub care only about themselves. Dee and Dennis are trying to help their friend, but they’re really only trying to make themselves feel smarter, putting their college psych classes to use in some sort of disturbing competition. Mac barely thinks about his friend, instead trying to serve his own ego.

Rob McElhenney (and the rest of the gang) have created memorable characters because they are so consistent. On a TV show, it’s perfectly common for the womanizer to mutate into a family man (see How I Met Your Mother.) Charlie, Dee, Dennis and Mac feel like real characters because they are allowed to be selfish and cruel. Unfortunately, this is what happens in real life. Most of us have a Crazy Uncle, right? He’s been Crazy Uncle forever and he’ll be Crazy Uncle twenty years from now.

The show is also compelling because the writers confront important issues in unexpected ways. The topic of child molestation is obviously very serious and unpleasant. However, people have all kinds of different reactions to different situations. The program does not make light of actual child molestation; instead, McElhenney is getting laughs at the expense of people who lie about having been molested. (Sadly, this happens in real life, too.) He is making fun of people who take one college class in psychology and then think they are Sigmund Freud. Most of all, the jokes are directed at people who do not have the “appropriate” reaction to child molestation.

What Should We Steal?

- Keep your characters consistent and human. Why bother writing ONLY about great people who never have or cause any problems? Personal change is not only a very long process, but it’s also rarer than we see it in literature. Real people sometimes make “inappropriate” jokes and express “inappropriate” thoughts. So should your characters.

- Write a new spin on big issues. Think about Lifetime movies. Can they be entertaining? Sure. But they can also wear you out because there are no surprises in the stories. Christmas movies are the same way. We know everything is going to work out at the end of the story. Most romance novels? The same thing. At the very least, the folks involved with It’s Always Sunny can be proud that they create an illusion of life that is much closer to reality than the world most TV writers create.

Television Program

2005, characterization, It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Rob McElhenney