Title of Work and its Form: “Perspective,” poem

Author: Laura Kasischke

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem debuted in Volume 32, Number 4 of New England Review. Denise Duhamel and David Lehman subsequently selected “Perspective” for The Best American Poetry 2013 and you can find the poem in that anthology.

Bonuses: This New York Times review of The Raising will make you want to pick up the book. Here is a poem Ms. Kasischke published in Poetry.

Want to see Ms. Kasischke’s appearance at the 2012 National Book Festival?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Similes and Metaphors

Discussion:

Ms. Kasischke’s poem is a fantastic example of the way in which a work of literature can be intensely personal to the author and audience alike. The first three stanzas of the poem consists of comparisons related to massive upheaval and emotional epiphany. After polishing up his or her lens, the narrator of the poem now understands the reality of the situation with respect to an unnamed “you.” Simple and graceful and beautiful.

So what can we steal? Well, look at the technique Ms. Kasischke uses in those first three stanzas. They’re a collection of similes, aren’t they?

- “Like the lake…”

- “Like the Flood…”

- “Like the sheet…”

- “Like the sheet…” (it’s a different sheet in a different situation.)

Ms. Kasischke is also a little coy with the other half of the comparison, allowing you to fill in the blanks with something related to your own life or experience. So why can’t we write a poem in which we make repeated comparisons in order to describe a situation or character. For example, who is…

“Faster than a speeding bullet. More powerful than a locomotive. Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound…”?

Why, it’s Superman, of course. If you didn’t know about him before, you have a great idea of his powers after absorbing all of those metaphors.

If we want to stay with similes, we can toggle over to “as.” How long will you love someone who is special to you? For example:

As around the sun the earth knows she’s revolving

And the rosebuds know to bloom in early May

Just as hate knows love’s the cure

You can rest your mind assure

That I’ll be loving you always

Oh…Stevie Wonder beat us to that idea.

But that’s okay. (Especially because Stevie Wonder is so incredibly talented and awesome.) You can create your own list of similes or metaphors that will, through repetition, create a powerful rhetorical response in your reader.

Ms. Kasischke splits the poem (in my view) into two explicit sections. The first three stanzas establish that something has changed in the narrator’s mind; he or she has reached some epiphany. The second half describes the method by which this result was achieved: “The polished lens.” Then the narrator informs the other person involved that he or she now knows the truth and that their relationship has changed. First section: expression of understanding. Second section: establishing consequences.

How did Ms. Kasischke make the transition so clear? She could have easily split the poem into explicit sections:

I

Like the lake…

…

II

And the sudden…

What did Ms. Kasischke gain by structuring the poem the way she did? Well, I love the way the poem flows. In this case, the “I” and “II” stop our eye and would be a bit of a roadblock to our progressive understanding of the poem. (You are free to disagree, of course!) Still, Ms. Kasischke did not leave us adrift; she made it very easy for us to understand what she was doing. How?

In the first three stanzas, Ms. Kasischke begins with four similes that employ “like” and then breaks the pattern with two more that omit “like.” The pattern has broken down…there must be something new coming. Further, the poet directly references a narrative and its “end” (in addition to its non-linear nature).

The next stanza pays off the hint of something new: “the sudden sense./ The polished lens.” The lines are different and there are no more uses of “like.” In fact, Ms. Kasischke even switches to “as if.” And then there’s that “you,” a HUGE move considering that we learn the poem is now directed at a specific person. We imagine this must be a separate section with a different intent.

See how we figure all of this out without being told in an explicit manner?

One last note…not a big one. Ms. Kasischke capitalizes “Flood” in the fourth line of the poem. I spent a couple of seconds wondering why. Now, the author may have a completely different idea-which is perfectly fine-but I think that the capital F is a reference to one of the creation story floods that you find in so many mythologies around the world. (I don’t want to assume which specific religion Ms. Kasischke might mean. You know what happens when you assume. You make an assu out of me.)

No matter which mythology she might be referencing, Ms. Kasischke, with the simple capitalization of a letter, ties the work into big-time stories that many people hold very close to their hearts. I guess I’m not the only one who feels bad for an insect in the sink, a creature who just can’t understand why a tidal wave is overtaking their safe haven. The fly is confused and hurt and scared. The same way that everyone but Noah and his family members must have felt during the Flood in the Old Testament. See? Choosing “F” instead of “f” has made me think about huge ideas.

What Should We Steal?

- List similes and metaphors to establish situation, emotion or character. Like a pound puppy who is brought home by a loving family, I’m grateful for all of my Great Writers Steal fans.

- Create sections in your work without section breaks. What are some other ways that you can create the effects we earn from big transitions without flat-out telling the reader you’re making a big change?

- Small changes in text can have big and meaningful ramifications. A capitalized letter or switch from a period to a semi-colon can give your work a whole new depth.

Poem

2012, Best American Poetry 2013, Laura Kasischke, New England Review, Similes and Metaphors

Title of Work and its Form: “Bravery,” short story

Author: Charles Baxter

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the Winter 2012 issue of Tin House and was subsequently chosen for Best American Short Stories 2013.

Bonuses: Here is an interview Mr. Baxter gave to Bookslut. Here is what Karen Carlson thought of the story. Mr. Baxter is the author of Burning Down the House, a fantastic book about writing craft. (Well, Graywolf only publishes fantastic books.) Mr. Baxter discusses the book in this interview with The Atlantic.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: White Space

Discussion:

This is, in a way, the story of Susan’s coming of age. We meet the young woman as a teenager who, unlike her friends, is attracted to men who are, above all, kind. Susan affirms her interest in college and finally meets Elijah, a pediatrician who devotes his time to caring for others. Before long, the two are married and on honeymoon in Prague. On one eventful day, the pair walks through a chapel whose walls are filled with carved babies. An omen? Then the pair are verbally accosted by a woman who shouts at them in angry Czech. An omen? Then Susan is grazed by a tram. An omen? These must have been omens, as Susan immediately finds herself pregnant. The last scene of the story finds Elijah feeding the baby. Susan insists he stop, whereupon Elijah goes on a walk that results in a thematically relevant experience.

There are a lot of eternal struggles for those who take up the challenge of storytelling. One of them is how to use white space and their asterisky cousin: the section break. When should we use white space? Unfortunately, there’s no absolute right answer. Like any other choice, white space creates an effect and it’s our job to decide if we’re creating the proper effect. Mr. Baxter uses white space in “Bravery” for many of the common reasons:

- To jump ahead in time.

- To emphasize a single image or experience. (Susan’s tree dream.)

- To afford him the chance to get in a cool end-of-section “punch.”

- To allow that “punch” to land and to reverberate in the reader’s mind.

- To control how fast the reader reads the story and the path of his or her eyes.

Mr. Baxter uses two asterisk section breaks in the story:

- After Susan and Elijah have met and Susan reflects upon his kindness.

- After the significant day in Prague; Susan-though she is unaware-is about to be pregnant, and her dream confirms much of what she believes about her “destiny.”

If you’re anything like me, you are wondering why Mr. Baxter put the section breaks where he did. The first section break seems to have the following effect:

- Mr. Baxter spends the first few pages running through a wide swath of Susan’s life. The asterisk lets us know that the narrator is going to slow down and that the next few pages will zoom in on a very brief period of time.

- Mr. Baxter seems to be whispering, “Okay, friend. I’m done shooting tons of exposition at you! Now that you know the basics, let’s go deeper into Susan’s thoughts and experiences!”

- The transition itself mirrors the journey being taken by the characters. Susan and Elijah are on a plane. This is down time. The couple left terra firma in one place and their lives resume in another. The story functions the same way. (The asterisk is an airplane in a way.)

The second section break functions thus:

- Mr. Baxter marks Susan’s transition from childlessness to parenthood.

- Mr. Baxter zooms ahead in time from one significant scene to another.

- Mr. Baxter switches between abstract poeticism and efficient exposition. (“They named their son Raphael…”)

So how should we use white space and section breaks? Sigh…there’s no easy answer. We just need to follow Mr. Baxter’s lead and make sure that our choices have the desired effect in our readers.

Another concept with which we always wrestle is the personality of our narrators. “Bravery” has a pretty straightforward third person limited to Susan’s perspective. There’s nothing wrong with the narrator; it’s your tried-and-true reporter. I did find significance in a sentence that arrives a few pages into the story:

He handed her a monogrammed handkerchief that he had pulled out of some pocket or other, and the first letter on it was E, so he probably was an Elijah, after all. A monogrammed handkerchief! Maybe he had money. “Here,” he said. “Go ahead. Sop it up.”

The bolded sentence is significant to me because it sounded as though the narrator was speaking in a different register. The sentiment seems to suggest a lot about Susan because it’s buried in the middle of “normal” stuff. Think of it this way. Let’s say you ask your significant other how his or her day was and you hear the following:

“Eh, just a normal day. I went to the post office, then I picked up some dog food. I was a couple minutes late to work, but it was okay. I had leftovers for lunch. I ran into my celebrity crush and we went on a long walk alone in the woods. I forgot to get gas on the way home, so I have to do that tomorrow morning. That’s about it.”

I’ll bet I know which part of that list you’ll ask more about! The extraordinary (in this case suspicious) sentence stood out among the rest. “Maybe he had money” stood out for me because it seemed different from the narrator’s other thoughts and shaped how I understood Susan to some small extent.

What Should We Steal?

- Employ white space and section breaks to create the desired effect in your reader. Most readers aren’t going to mark up your stories with a pen and wonder why you did what you did. They are going to absorb these breaks subconsciously.

- Spice up your narrator as carefully as a chef spices a dish. If your narrator is that traditional laid back third person limited, you probably shouldn’t jazz things up TOO much. But a little bit of jazz? That can make your story pop.

Short Story

2012, Best American 2013, Charles Baxter, Tin House, White Space

Title of Work and its Form: “Malaria,” short story

Author: Michael Byers (on Twitter @The MichaelByers)

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the Fall 2012 issue of Bellevue Literary Review. The kind folks at the journal have made the story available online. “Malaria” was subsequently selected for Best American Short Stories 2013 and is included in the anthology.

Bonuses: Here is an interview Mr. Byers gave to Hot Metal Bridge. Here is where you can find the books Mr. Byers has published. (In addition to works published by people who have similar names.) Here is what Karen Carlson thought of the story. Here is the book trailer for Percival’s Planet:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Opening Passages

Discussion:

Several years ago, Orlando was in the blush of first love with a woman named Nora. But this is not a love story. Instead, Orlando is working out his understanding of George, Nora’s brother. George is an adult, but has some mental health concerns. The man was getting by, but had a bit of an incident that exacerbated Nora’s worries about herself and her future.

Yes, I’m being a bit vague in the summary. Why? Mr. Byers has given us a story that is not about a bang-bang narrative. Instead, the gentleman seems to want to explore the effect of mental health issues on the people who love the afflicted. Mr. Byers makes the very wise choice of keeping the story comparatively short; the slack narrative feels just fine in a story of this length.

The first thing I would like to point out is the skillful way in which Mr. Byers begins his story. Unfortunately, I read this piece just a little too late to include it in my video about the topic.

Let’s look at the first two sentences:

When I was in college in Eugene I had a girlfriend named Nora Vardon. We had fallen together sort of accidentally, I talked to her first at a vending machine where we were both buying coffee, and things progressed in the usual slow ways, we went out one cold night to look at the blurry stars, and that led to some kissing, and from there we started the customary excavation of our families, revealing, not quite competitively, how crazy they both were, she with a raft of depressives and schizophrenics and me with a bunch of drunks, mainly the men on my father’s side.

What has Mr. Byers packed into the opening passage?

- POV. We know it’s a first person story.

- Time frame. We know that the story took place some time ago, when the narrator “was in college.” The narrator also describes the love affair with the kind of wistful regret that is only granted with distance and earned wisdom.

- Diction. Mr. Byers gives us a beautiful second sentence that is enjoyable on its own.

- Subject matter. Romance takes a backseat to the real theme, which relates to mental illness.

- Internal narrative logic. Mr. Byers begins at the beginning of Orlando’s relationship with the Vardons, the central conflict/issue in the story.

Take a look at the first few sentences of one of your own stories. Are you packing in as much as Mr. Byers does?

A line or two later, Mr. Byers did something that seemed quite significant to me. (Your mileage may vary, of course.) I loved the sad suggestion of the tense Mr. Byers used in this sentence:

She had an open, genial, feline face, with big cheeks and dark eyes, and a big soft body that was round in parts…

Nora “had” an open face. We’ve only just begun our journey with Orlando, but that “had” is extremely suggestive. What is going on with Nora now? Is she okay? Are they just not together? Did they have a meaningful relationship? We may not have these questions had Mr. Byers cast the sentence differently:

- My old girlfriend had…

- Nora, my college girlfriend…

- I loved her open, genial, feline face…

- Nora, bless her heart, was a beautiful woman with a…

Instead, Mr. Byers has Orlando tell us that Nora “had” that face. (“Gee…I hope nothing happened to it.”) I guess I’m urging us to think deeply about how we use tense in our work. Think back to your first real breakup. The one that wrenched your heart and made you wear all black to school the next day. What should you say if you’re trying to convince others that the long-ago heartbreak isn’t a problem for you now?

- Sally broke up with me before graduation. (past simple)

- Sally was breaking up with me before graduation. (past continuous)

- Sally had broken up with me before graduation. (past perfect)

- Sally had been breaking up with me before graduation. (past perfect continuous)

Each sentence means pretty much the same thing, but the tense employed in the sentences carries a different meaning.

What Should We Steal?

- Pack your opening passage full of everything your reader needs to understand your story. The longer you take to introduce important elements, the greater the chance you lose your reader.

- Choose the tense that carries the subtextual meaning appropriate to your work. “The divorce meant nothing to Sally” or “The divorce HAD meant nothing to Sally”?

Short Story

2012, Bellevue Literary Review, Best American 2013, Michael Byers, Opening Passages

Title of Work and its Form: “Sotto Voce: Othello, Unplugged,” poem

Author: Tim Seibles

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem made its debut in the Fall/Winter 2012 issue of Alaska Quarterly Review, a journal so consistently good that you’re not even angry when they reject you. Denise Duhamel and David Lehman selected the poem for The Best American Poetry 2013.

Bonuses: Mr. Seibles is a highly accomplished poet; why not consider purchasing one (or another) of his books from your local independent bookstore? Here is an interview Mr. Seibles gave while serving as the 2010 Poet-in-Residence at Bucknell University.

Mr. Seibles gave this wonderful TEDx talk about poetry:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing:

Discussion:

Through the course of eleven stanzas, Mr. Seibles offers us a glimpse into the mind of one of Shakespeare’s most intriguing tragic heroes. Othello is ostensibly explaining himself to Iago, but the “brave Moor” is confessing to himself, working through his own guilt in the context of the self-understanding he has gained through the course of the play.

The first thing to mention is that Mr. Seibles engaged in the tried-and-true act of simply playing in the sandbox of another writer. (The Bard of Avon has been dead for nearly 400 years, so there’s certainly no possible ethical conflict.) I love how the poem does double duty. One on hand, it’s a creative work about a deep character whose thoughts help us understand our own. On the other hand, it’s a work of literary criticism. Mr. Seibles offers his interpretation of Othello and his motivations by putting words into his mouth. (Just like Shakespeare did!)

There are so many fantastic opportunities for this kind of poem.

- We certainly got Medea’s thoughts…what was Jason really thinking about her actions?

- Aren’t you curious as to what Liza-Lu (Tess of the D’Urberville’s daughter) thinks about her mother when she has her own child?

- What does Mephastophilis/Mephostophilis say to the NEXT guy?

Mr. Seibles offers us some excellent insight in the note he included with his bio in Best American Poetry. He says,

I wanted the stanza variations to be the visual equivalent of the players: Othello alone, he and Desdemona, the couple, and, of course, the poison triumvirate.

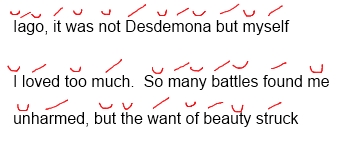

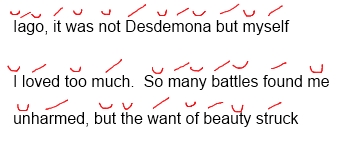

If you re-read the poem with that concept in mind, the conceit seems even cooler. The stanzas have the following number of lines:

1, 2, 3, 1, 2, 3, 2, 1, 2, 1, 1

While the “reliable pattern” breaks down, Mr. Seibles’s concept remains cool and appropriate. Look at the last two stanzas…can’t we all agree that Othello is “alone?” I love what Mr. Seibles did with the stanzas because he is writing in service of his primary duty. Now, Shakespeare wrote in far more definite (and restrictive) forms. The lines of verse were in iambic pentameter. The sonnets had fourteen lines (three quatrains and a couplet). Even though Mr. Seibles fails to follow the rules of any established form, he is careful to make sure that the poem does indeed follow its own internal logic. The number of lines per stanza correlates to the perspective from which it is emerging.

While the lines are not iambic, they still have that kind of iambic pentameter feel:

(You’ll also note that the second line should count as iambic pentameter, not withstanding that final foot.)

(You’ll also note that the second line should count as iambic pentameter, not withstanding that final foot.)

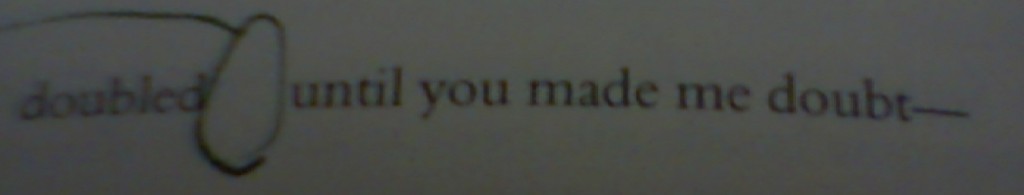

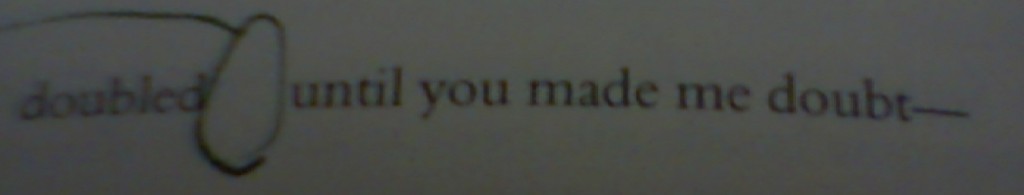

Mr. Seibles also points out another way in which he fits the form of the poem to the conceit that inspired him. Check out the eighth stanza:

Yes, I used my fountain pen to mark the space between the first and second words. (And yes, I took the picture with the camera on my cheap media player because it’s all I have.) This extra space is a representation of Mr. Seibles’s desire to let the lines “breathe as we might imagine sad Othello did.” So Mr. Seibles violates the “rules” of composition, but does so for the most beautiful and important reason: in the service of the emotion he wanted to communicate and the story he wanted to tell.

What Should We Steal?

- Put your own stamp on the literary legacy of a classic. Public domain works are just that…they belong to all of us. What do you think the Wicked Witch of the West’s early years were like? (Shoot. That one has already been done.)

- Ensure that your piece follows some kind of form, even if that form is specific to that work alone. All creative works must adhere to internal logic. Citizen Kane is one of the best films ever made, even though it follows its own rules, not those of the conventional three-act structure.

Poem

2012, Alaska Quarterly Review, Denise Duhamel, Desdemona, I Never Gave Him Token, Tim Seibles, William Shakespeare

Title of Work and its Form: “Divine,” poem

Author: Kim Addonizio

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem was first published in the Spring 2012 issue of Fifth Wednesday Journal. The incredible Denise Duhamel and David Lehman chose the poem for the 2013 volume of Best American Poetry.

Bonuses: Poet John Gallagher offers some excellent analysis of the poem; there’s also an interesting discussion in the comments. Ms. Addonizio is EVERYWHERE, folks. Here is her Poetry Foundation page. Here is an interview Ms. Addonizio gave to Poetry Daily. Poetry, of course, is usually best enjoyed in performance. Here are some examples of the poet reading her work:

Ms. Addonizio is certainly a fascinating woman; here she is performing with a blues band:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Free Verse

Discussion:

Guess what. You’re stuck in the dark woods, a place where you are at risk of being flayed by werewolves and of meeting those creatures humans have created to keep their children in line. Ms. Addonizio addresses YOU in the poem, using that second person swag to immerse you in a place rife with:

black trees

hung with sleeping bats

like ugly Christmas ornaments.

As the poem ends, “you” are left impotent and alone in a scary and dangerous place.

Okay, so this poem is in free verse. Even though I love poetry (and all writing) of all kinds, free verse has always been a bit of an enigma to me. There isn’t much obvious structure, is there? No meter, no rhyme. As Robert Frost said, writing free verse is like playing tennis with the net down. Ms. Addonizio’s poem is a good example of how free verse DOES have a structure and how poets are definitely working within a series of rules in order to create.

Here’s the big lesson that fiction writers and other free verse averse folks can learn from “Divine.” Even though the poem somewhat resembles a stream-of-consciousness explanation of a dream, each line of the poem is interesting. Each line is a little poem unto itself.

Prose writers can take hundreds of thousands of words to make their ultimate point; poets have a far smaller canvas. There’s a lot more margin for error in a short story, too. So a sentence sounds crummy to the ear or a paragraph represents a little bit of a tangent…that’s fine. There are countless additional opportunities for the writer to impart meaning.

Poets don’t have that luxury. That’s why Ms. Addonizio ensured that each line had SOMETHING going for it…even if it’s only two words long.

oozing mayonnaise.

See? Two words long. Why shouldn’t Ms. Addonizio have simply hit “backspace” to put those two words on the previous line? In this case, the words evoke a very powerful and visceral image. (And a gross one.) Oozing mayonnaise. Ew. The line also forces you to exercise your lips. Read it aloud. You have to go from the OOOOO to the AAAAAHHH. Your lips pursed, then your mouth completely open.

Another example:

If you had a real one you could stab

Okay, okay. What do we appreciate about this line in isolation? Well, it sets up the next line, allowing “your undead love” to exist on its own. I also love the momentum of the line. Commaless, we run into that powerful verb without much warning. “Stab” is a scary verb, isn’t it?

I also admire that the poem is abstract…but not too abstract. Reading some poems, you’ll agree, make you feel as though the poet is daring you to get some meaning out of the lines. (My students often experience this sensation. It’s an unpleasant cycle. The only way to “get better” at reading poems is to…read poems.)

Ms. Addonizio mentions that “you watched the DVDs that dropped/ from the DVD tree.” Someone like my father-a smart man, but not much of a poetry reader-might struggle with the abstraction momentarily. There’s no such thing as a DVD tree! But when you think about it for a while, having been primed by the other “fantastic” concepts Ms. Addonizio uses in the poem, it kinda makes sense. You can conceive of some kind of “DVD tree.” (And if you think about it, is Redbox all that different from a DVD tree?)

Ms. Addonizio writes,

Ping went your iHeart

What?!?!? There’s a new product from Apple called the iHeart? type-a…type-a…type-a…type-a…type-a…wait for the network…click-a…click-a…click-a…click-a…

Hey, there’s no iHeart scheduled for release! Oh…Ms. Addonizio is making a comment about the rote, mechanical nature of romance and attraction to which we all sometimes fall prey. See? The accessible abstraction allowed her to engender complicated and interesting thought. (And she was able to do so with just six characters!)

What Should We Steal?

- Make the most of each line, particularly in free verse. Go through each line to make sure there’s SOMETHING for the reader to enjoy.

- Keep your abstraction accessible. Even if you never meet the person who is reading your poem, you are still performing for them. You don’t have to take them by the hand…but you should at least hook your pinky into theirs as you lead them along.

Poem

2012, Best American Poetry 2013, Fifth Wednesday Journal, Kim Addonizio

Title of Work and its Form: “The Wilderness,” short story

Author: Elizabeth Tallent

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was first published in Spring 2012’s Issue 129 of Threepenny Review one of the top journals out there. Elizabeth Strout (and Heidi Pitlor) chose the story for the 2013 edition of Best American Short Stories and it can be found in the anthology.

Bonus: Here is what Karen Carlson thought of the story. Here is “Little X,” a piece of memoir that Ms. Tallent published in Threepenny Review. Here is Ms. Tallent’s page at Powell’s Books.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Compensation

Discussion:

The third-person protagonist of the story is an English professor who is endlessly fascinated by her students’ preoccupation with machines. The young people are seemingly addicted to the bleeps and bloops that make it clear that the devices are alive. The professor was enthralled by a different object as a child: a mummy that helped her understand death and the meaning of history. The strongest bit of narrative relates to this struggle between history and inanimate objects: Wal-Mart wants to plow over the woods of The Wilderness to build a new story. The narrator’s great-great-grandfather nearly became a casualty of war on that ground. The story ends as the narrator reconsiders what it means to elude death and to live life. (It was also my impression that Ms. Tallent makes the case for literature in the story; Shakespeare’s body was not immortal, but he’s still with us and will be until the final human breathes his or her last.)

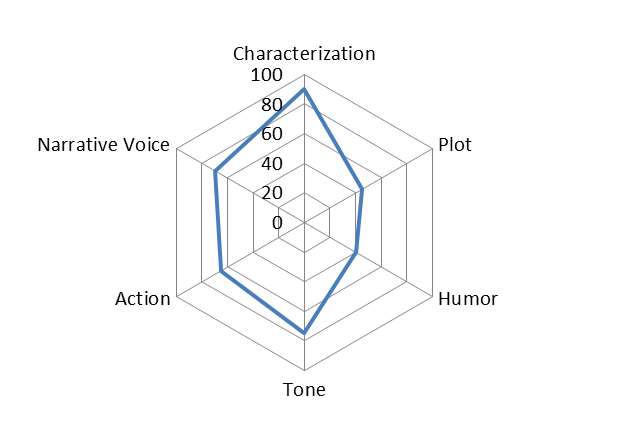

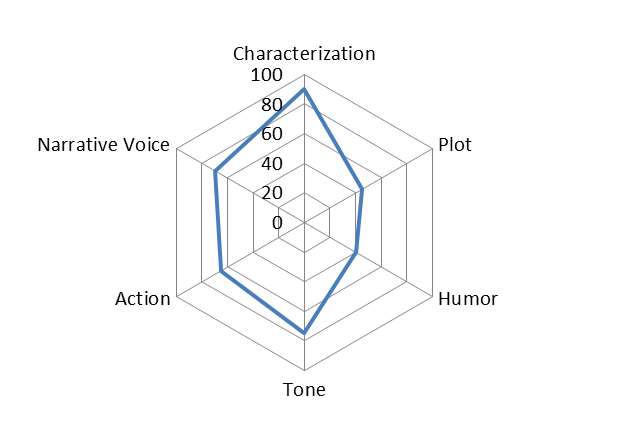

We can all certainly agree that “The Wilderness” is not a white-knuckle barnburner with a complicated plot. We’ll also agree that plot is an important part of a story. So why aren’t we upset with Ms. Tallent? It’s easy: she makes more potent use of the other tools in the writer’s toolbox in order to compensate. We all love the eerie inevitability of the plot of “The Lottery,” for example. Stuff is always happening in that story; people file into the town square, slips are drawn from the box, and men, women and children pick up stones. The narrative thread of “The Wilderness” is not as strong as that of “The Lottery” and that’s perfectly fine because Ms. Tallent offers extremely potent characterization to help us understand the professor. Ms. Jackson’s sentences in “The Lottery” have a beauty about them, but the sentences must, by necessity, take a backseat to the plot. Unbound by a similar obligation, Ms. Tallent offers us sentences that are a joy unto themselves.

Here’s a chart I made for a previous essay that illustrates my point. (I would love to believe that every GWS reader has gone through every essay, but I know it’s not the case.) A story is like a spider web or a net. A web or a net can have odd dimensions and it can even have holes, so long as the other parts of the structure are strong enough to hold it together. The plot of “The Wilderness” may not, as Nigel Tufnel might say, go to eleven. Other facets of the story, however, DO go to eleven (which is one louder), ensuring that the story is coherent and enjoyable.

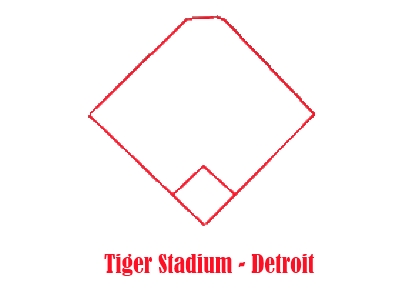

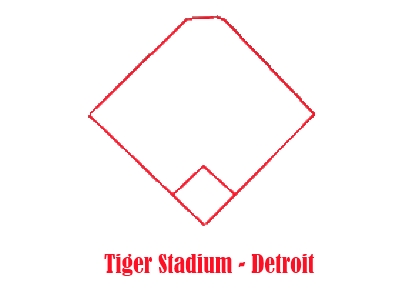

Let’s think of it another way. Spring Training is going on as I write this. (My beloved Tigers are trying to figure out what they are going to do at short.) Until 1999, the Tigers played baseball at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull, filling the stands of the most beautiful ballpark ever. Look at the dimensions of Tiger Stadium:

Let’s think of it another way. Spring Training is going on as I write this. (My beloved Tigers are trying to figure out what they are going to do at short.) Until 1999, the Tigers played baseball at the corner of Michigan and Trumbull, filling the stands of the most beautiful ballpark ever. Look at the dimensions of Tiger Stadium:

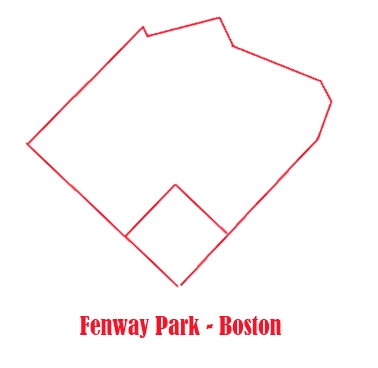

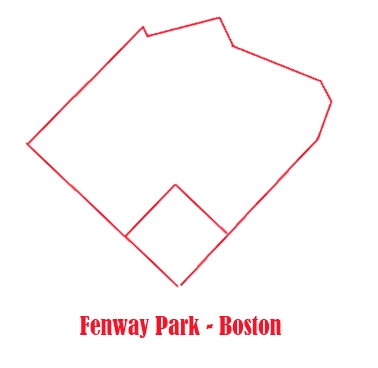

See how even? See how beautiful? Now THAT’S an outfield. Baseball is a rare sport whose playing field isn’t completely regulated by the rules. Yes, the bases must be ninety feet apart, but the shape and dimensions of the outfield vary wildly between ballparks. Think about Fenway Park. The builders had a bit of a problem: the street running along left field was very close to home plate. See:

See how even? See how beautiful? Now THAT’S an outfield. Baseball is a rare sport whose playing field isn’t completely regulated by the rules. Yes, the bases must be ninety feet apart, but the shape and dimensions of the outfield vary wildly between ballparks. Think about Fenway Park. The builders had a bit of a problem: the street running along left field was very close to home plate. See:

How did the builders compensate? Why, they made the left field fence extremely high. (It’s that “Green Monster” you’ve heard so much about.) If that fence were five feet high, each Red Sox home game would have a score of 23-22.

How did the builders compensate? Why, they made the left field fence extremely high. (It’s that “Green Monster” you’ve heard so much about.) If that fence were five feet high, each Red Sox home game would have a score of 23-22.

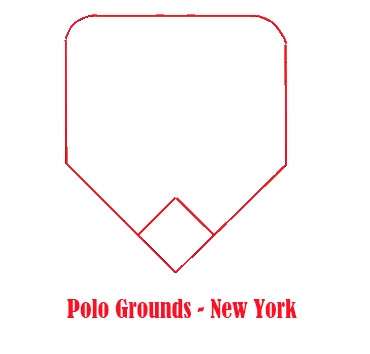

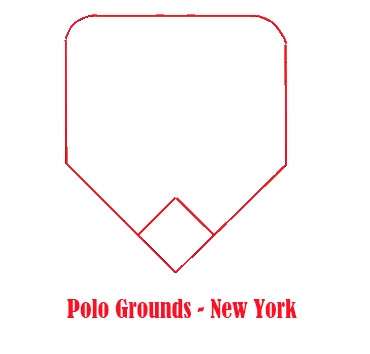

Check out the dimensions of the Polo Grounds, the former home of the New York Giants (and briefly the Yankees and Mets).

No, you’re not seeing things. You’re seeing why they called it the “polo grounds.” Each foul pole was really close to home plate, so the fences were higher. The Giants also compensated for those generous porches in right and left by making center field a vast wasteland where home runs go to die. (Or to turn into doubles.)

No, you’re not seeing things. You’re seeing why they called it the “polo grounds.” Each foul pole was really close to home plate, so the fences were higher. The Giants also compensated for those generous porches in right and left by making center field a vast wasteland where home runs go to die. (Or to turn into doubles.)

Wasn’t that a fun and unexpected way to consider my point? When one facet of our work is, by design, a little weak, we must compensate by adjusting the prominence of the other facets. Would Alfred Hitchcock have chosen “The Wilderness” as the basis for his next suspense film? Probably not. He would, however, have admired the story’s depth of characterization and its philosophical underpinnings.

Another facet of “The Wilderness” that I admire is the way that Ms. Tallent encouraged me to think about BIG ISSUES in a graceful manner. She made her character think about them first. “She” doesn’t seem to have liked her former colleague very much, but his flirtatious question has had her thinking ever since he asked what she would want on her tombstone. Now, Ms. Tallent is not forcing us to think too much. That would be a violation of the writer’s First Duty. (It’s the writer’s job to do all of the work so the reader can have all of the fun.) Ms. Tallent is, however, inviting us to think big thoughts. Invitations are fine; dictates are not.

Have you ever been asked, for example, which three books you would take with you to a desert island? Which family member would be the first you rescue from a burning building? These are difficult questions to answer when you’re put on the spot. Instead, Ms. Tallent simply offers up the question for her character; we can choose whether or not we want to address it.

What Should We Steal?

- Boost the power of other parts of your work when another part is a little weak. Okay, so you’re writing Transformers 8: The Planet of the Machines. Each of the characters are named “Guy” and “Girl” because the characters in the Transformers movies are irrelevant. There better be some pulse-pounding action scenes in the script to make up for it.

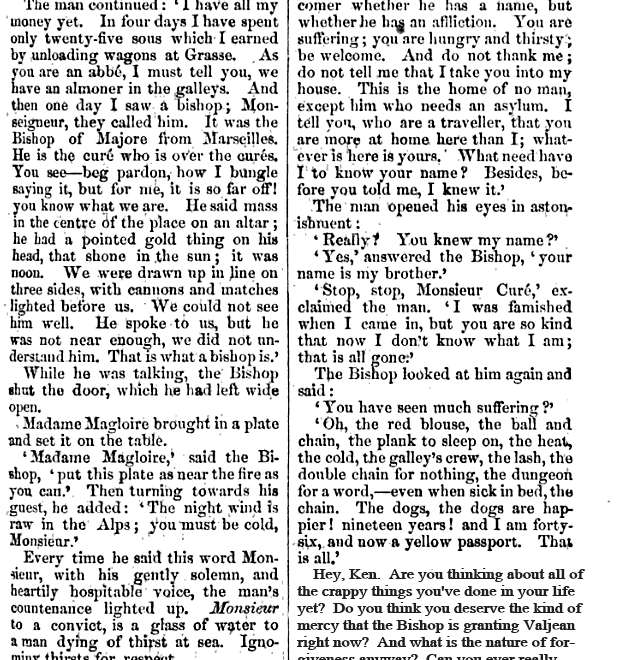

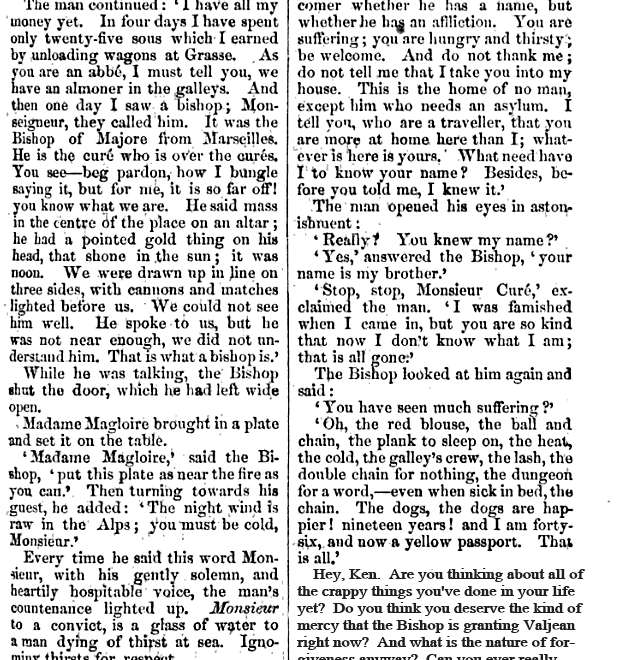

- Ensure that any deep thought on the part of the reader is voluntary and earned. I think about the nature of humanity and our responsibilities to each other when I read Les Miserables. I probably wouldn’t do so if Victor Hugo did something like this:

Short Story

2012, Best American 2013, Elizabeth Tallent, Narrative Compensation, Threepenny Review

Title of Work and its Form: “Nemecia,” short story

Author: Kirstin Valdez Quade

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was first published by Narrative Magazine. You can find the piece here. “Nemecia” was subsequently chosen for the 2013 volume of Best American Short Stories.

Bonus: Here is “The Five Wounds,” a story Ms. Quade published in The New Yorker. Here is another story Ms. Quade published in Guernica. Here is what cool writer Karen Carlson thought of the story.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Objects

Discussion:

Maria looks back on the time she spent with her cousin Nemecia with a kind of bittersweet love. The title character suffered a terrible family tragedy, necessitating a move to Maria’s home. Many years have passed since the two young women lived together; Maria (the first person narrator) wasn’t always happy that her cousin was around. And why would she be? Nemecia got all of the attention because of the misfortune she experienced. Nemecia is older and eats ravenously. Ms. Quade includes a beautifully written example of another of Nemecia’s crimes: she would dig her thumbnail into Maria’s cheek each night, creating a scar. Maria can only take so much; after her cousin ruins one of her rites of passage, she says something she can’t take back and is sent away for a little while. In the present day, Maria remembers Nemecia with the understanding she couldn’t muster in her younger years.

Ms. Quade knows she has a lot of exposition to dole out. In addition to the expected basics, she needs to let us know when Maria is telling the story. She needs to place the dramatic present of the flashbacks. She needs to set up the “mystery” of Nemecia’s tragedy. Perhaps her most difficult move: Ms. Quade needs to establish the different attitudes Maria holds as a grownup and as a child. What is Ms. Quade’s first move? How does she streamline some of the exposition? What device does she use that allows her to explain a lot in a felicitous manner? A photograph. The story begins,

There is a picture of me standing with my cousin Nemecia in the bean field. On the back is penciled in my mother’s hand. Nemecia and Maria, Tajique, 1929.

The photograph is a very logical entry point for the story. Not only is it a firm piece of documentary evidence-it’s a picture, after all-but it nudges the reader into something of a visual mindset, mimicking the response he or she might have if they were actually looking at a picture. Another reason that the photograph works is that these objects are (by definition) representations of the past. After absorbing the mental image, we’re primed to enjoy a short story that takes place primarily in flashback.

So, a spoiler alert would be inappropriate when I tell you that Nemecia is dead at the time when Maria is recalling the story. Here’s why it’s not a problem. This kind of rote statistic really isn’t important for Ms. Quade’s purposes. It seems that the author’s intent was to tell us a meaningful story about Nemecia and the relationship between the cousins. It really doesn’t matter what jobs Nemecia may have had in her working life or how old Nemecia was when she passed. All that matters is what happened between the women when they were teens and how the two (especially Maria) learned to understand the other on a deeper level. I don’t believe Ms. Quade tells us the name of Nemecia’s husband…but that doesn’t matter. We DO care that Nemecia has apparently changed her name as part of the process of leaving her past behind.

Think about the Star Wars prequels. (But just for a moment. Then you can go back to pretending they don’t exist.) When The Phantom Menace was released, we all knew quite well how Anakin Skywalker/Darth Vader met his end. All of that suspense was already gone as we went into the theater to see that film, our hopes about to be crushed like an empty soda can rolling onto a busy freeway. Why wasn’t this a problem? We were going to find out WHY Darth Vader turned to the Dark Side. WHERE he began. HOW he learned to use his Jedi powers. WHO taught him how to sound more like a robot than R2-D2 when talking to a woman. The Star Wars prequels and “Nemecia” have at least one thing in common: both are stories that emphasize the journeys undertaken by the characters, not their ultimate destinations.

What Should We Steal?

- Employ an object as the entry point of your story. While it’s possible to do so in a clunky manner, it’s perfectly natural, for example, for a first-person narrator to tell a story about the grandfather who owned the fountain pen he’s holding.

- Maintain focus on the truth of your character, not the boring details. Whatever. Jean Valjean dies at the end of Les Miserables. The death itself doesn’t matter; We (and Hugo) care about what Valjean accomplished with his life.

Short Story

2012, Best American 2013, Kirstin Valdez Quade, Narrative Magazine, Objects

Title of Work and its Form: The Three-Day Affair, novel

Author: Michael Kardos (on Twitter @michael_kardos)

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book was published by The Mysterious Press, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic. You can find it at your local independent bookstore. If you don’t know where your closest indie shop is, check here. I got my copy from The River’s End Bookstore in Oswego, NY. The book can also be ordered online, of course.

Bonuses: Here is what some smart guy thought about Mr. Kardos’s story, “Maximum Security.” (Oh, wait. That was me.) Here is Mr. Kardos’s interview with Brad Listi on his Other People podcast. Here is a very good review of the book from Spinetingler.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Will, Jeffrey, Evan and Nolan have been lucky enough to remain friends since their Princeton days. Sure, they don’t see each other very often. Getting together is hard; Jeffrey is a dot-com zillionaire, Evan is a hard-charging lawyer, Nolan is on his way to taking over Missouri politics and Will…well, Will is doing better. He witnessed his bass player get shot and killed in drive-by crossfire. He’s busy running a New Jersey music studio. No matter their busy schedules, the four men always make time for each other; they spend a week playing golf, eating steak and touching base.

Everything is great! Until the INCITING INCIDENT. (Or the turning point of Act One.) Jeffrey needs to get something from a convenience store, so they pull in. In a couple minutes, Jeffrey shoves the young clerk into the car and shouts, “Drive!” Will drives. This is a mystery/noiry-type book, so I don’t want to say too much more. Just read the book if you haven’t already; it’s great!

So, I don’t ordinarily like to create GWS essays about writers I’ve already featured. There are so many great storytellers out there and I want to feature as many of them as I can. On the other hand, I really liked the book and this is my site and I can do whatever I want. (I can’t really say that about too many other facets of my life.)

Mr. Kardos is probably quite justifiably proud of the favorable note The Three-Day Affair received from The New York Times Book Review. One of Ms. Stasio’s comments challenges me with respect to my experience with the book. “The plot,” she writes, “is original, if distinctly bizarre.” Now, I’m certainly not engaging in a respectful disagreement with someone like Ms. Stasio, someone with tremendous qualifications. I’m just not sure how I feel about her description of the plot, as the basic structure felt very familiar to me. In the prologue, we learn about the first-person narrator (Will) and what led him to move from New York City to the ‘burbs. The dramatic present picks up in Chapter 1. And Chapter 1 is pretty sweet. The four men care for each other deeply…they’re making good money…most of them have loving wives…Will is going to be able to start his record label…all is well.

Then boom-page 25 brings the kidnapping that starts the actual plot.

It’s certainly not a knock on Mr. Kardos or Ms. Stasio, but the book employs the tried-and-true structure for a noir/thriller/mystery.

- The first 100 pages of The Firm are great. Mitch is making money, he and Abby have a great relationship; all of his hard work is paying off. THEN THOSE TWO ATTORNEYS GET KILLED.

- In Strangers on a Train, Guy has his normal life. Sure, he’d like to ditch his wife, but things are looking up with the senator’s daughter. THEN BRUNO PROPOSES THE CRISS-CROSS MURDERS.

- Jimmy Stewart broke his leg, but things could be worse. After all, Grace Kelly is his girlfriend. THEN HE STARTS SEEING ALL OF THAT CRAZY STUFF OUT OF HIS REAR WINDOW.

- Marion Crane can’t afford to get married, but at least she has a boyfriend, a good job, a trusting boss…THEN THAT RICH GUY COMES IN AND PLOPS FORTY GRAND IN HER LAP.

- Will, Jeffrey, Evan and Nolan have their health, they ostensibly have a little money, they’re getting together for a week together. THEN JEFFREY SNAPS AND KIDNAPS THAT GIRL.

If you’ll notice, the THEN often happens around the Page 25 mark, just as the THEN often occurs around the MINUTE 15 or MINUTE 30 mark of a film. The book also mildly reminded me of the excellent 1998 film Very Bad Things. Here’s the trailer:

So five guys head to Vegas for a bachelor party. Then one of the guys accidentally kills the young lady who has come to “dance” for them. So the murder is an accident and the other four men are more complicit with each moment that passes. Should the guys protect their friend or go to the police? How do they handle their “105-pound” problem?

Like Very Bad Things, The Three-Day Affair does something wonderful. The characters are placed into a situation that tests their senses of morality. The stakes are constantly raised, of course, so what seemed okay two days ago (driving away from the store) becomes nothing in comparison with what seems okay in the present. Mr. Kardos’s book uses the changing dramatic situation to ask a number of important questions:

- How far would you go to help a friend?

- What’s more important? Your family or your good name?

- How do you get people to forget or to live with the bad things you’ve done to them?

- What’s the proper price of betrayal?

Mr. Kardos certainly doesn’t neglect his primary obligation; he tells us a rip-roaring story that you won’t forget for a while. But he does encourage the reader to consider deep and important thoughts. Will any of us, for example, be in the same situation as Mike McQueary, the man who walked in on Jerry Sandusky, well, raping a small boy? Probably not. (Thank goodness!) We will, however, be confronted with moral and ethical dilemmas that test us. What do we do in the moment? What do we do an hour later to atone for our failings in the moment already passed?

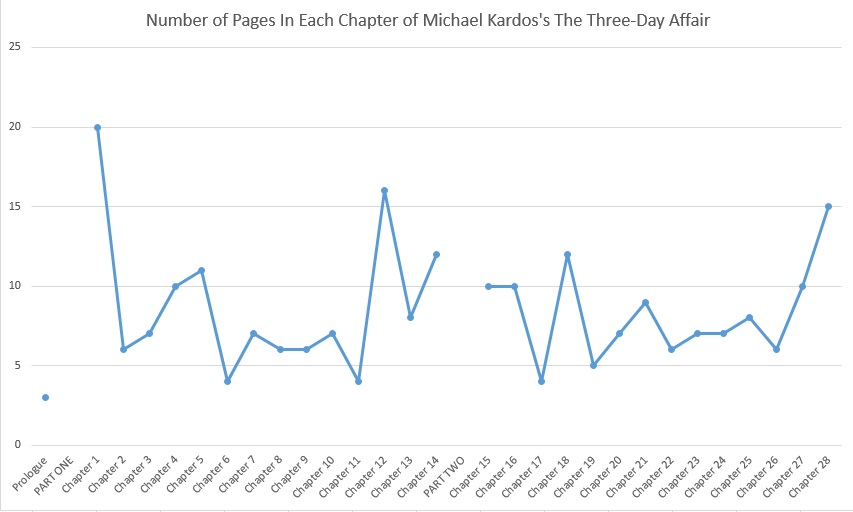

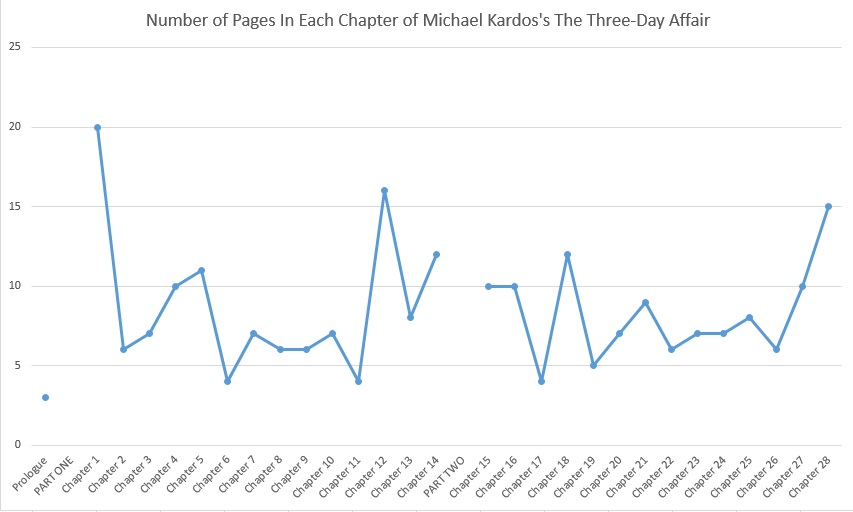

The world-class writer and teacher Erin McGraw would advise us, I think, to abandon our mistrust of numbers. (We are writers, after all.) So I’ve counted the length (in pages) of each of The Three-Day Affair‘s chapters.

Prologue: 3

PART ONE

Chapter 1: 7-26 (20)

Chapter 2: 27-32 (6)

Chapter 3: 33-39 (7)

Chapter 4: 40-49 (10)

Chapter 5: 50-60 (11)

Chapter 6: 61-64 (4)

Chapter 7: 65-71 (7)

Chapter 8: 72-77 (6)

Chapter 9: 78-83 (6)

Chapter 10: 84-90 (7)

Chapter 11: 91-94 (4)

Chapter 12: 95-110 (16)

Chapter 13: 111-117 (8)

Chapter 14: 118-129 (12)

PART TWO

Chapter 15: 133-142 (10)

Chapter 16: 143-152 (10)

Chapter 17: 153-156 (4)

Chapter 18: 157-168 (12)

Chapter 19: 169-173 (5)

Chapter 20: 174-180 (7)

Chapter 21: 181-189 (9)

Chapter 22: 190-195 (6)

Chapter 23: 196-202 (7)

Chapter 24: 203-209 (7)

Chapter 25: 210-217 (8)

Chapter 26: 218-223 (6)

Chapter 27: 224-233 (10)

Chapter 28: 234-248 (15)

And you know I love my literature-related charts:

What’s the point of all of this math-type stuff? Well, you can really see into Mr. Kardos’s thought process with regard to plotting. Look at the anomalies. There must be a reason Chapter 1 is so long, right? Well, he’s setting up the relationship between the men and painting a happy relaxed scene…so he can shake things up with Jeffrey kidnaps the girl.

Why is the last chapter so long in comparison? I’m going to be a bit vague, but the very beautifully written scene offers a motivation for the events of the whole book while complicating the narrative.

I should also point out that the line often looks like a roller coaster. Why would that be? You follow a fat Pope with a skinny Pope. The longer scenes tend to consist of high-octane suspense and the shorter scenes are a lot calmer connective scenes that prepare the next jolt.

What Should We Steal?

- Appropriate the structure of the classics. Look: Psycho worked in 1960. It works now and it will work a hundred years from now. You start out with a sunny and very normal day…then you bring in a lot of complications.

- Confront your reader with a series of deep moral dilemmas. Great drama comes from asking your audience to debate right and wrong.

- Consider the length of your chapters and scenes. Are you giving your reader enough time to recover from the gut punches you’re doling out?

Novel

2012, Megan Abbott, Michael Kardos, Narrative Structure, Noir, Ohio State, The Three-Day Affair

Title of Work and its Form: “Reading Fast and Slow,” nonfiction

Author: Jessica Love (on Twitter @loveonlanguage)

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece made its debut in the Spring 2012 issue of The American Scholar, one of the great magazines that you should be reading. As of this writing, Ms. Love’s piece is available online.

Bonuses: Ms. Love is a blogger for The American Scholar. You can check out her “Psycho Babble” column here. Ms. Love teamed with Abby Walker to write a paper for Language and Speech. If you have strong database searching skills and access, you can find the article here. If you don’t know how to find things in databases, ask your local librarian and he or she will be overjoyed to help you make your way to knowledge. Jenny Cheshire has written a bit of commentary on the paper that may help those of us who wasted our lives by not getting a doctorate in linguistics. (I’m being serious, of course.)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Openings

Discussion:

Ms. Love confronts a very important issue in this article: how we read. More importantly, she offers advice as to how we should read. Through the course of the article, she discusses the Slow Reading movement and how the Internet has changed the way we absorb information from what we read. Sure; skimming can give us the basics of an author’s story or a writer’s argument. Reading at a gallop or at a trot, however, runs counter to the simple mechanics of how our brains work. These Internet-friendly methods of “reading” prevent us from engaging a piece on the comprehensive level it may deserve. (I’m proud to say that I remembered Falstaff’s first name; he’s “Sir John,” of course.)

Look how Ms. Love opens her piece. She does something that I…well, I was going to say, “love.” I deeply admire when a nonfiction writer constructs an essay in this manner. A lesser writer may have begin with some blah blah blah about cognition or brain structure or something. Instead, Ms. Love begins her essay with an interesting anecdote that immerses us in her subject: “In 1986, an Italian journalist named Carlo Petrini became so outraged by the sight of a fast-food restaurant near Rome’s Spanish Steps that he ended up spawning a movement.” She goes on to describe the Slow Food movement and how the concept spread to other facets of human endeavor. Other writers may have begun the piece with one of the paragraphs that occurs later in the piece. What does she gain from beginning in this way?

- People love stories. After reading about Mr. Petrini, we are naturally inclined to care about the gentleman’s ideas because we’ve heard a little bit of his story.

- This neurological stuff can be pretty dry. The opening anecdote invites us to overcome our fears. Ms. Love is not going to bore us; she’s just communicating complicated ideas in a simple fashion.

- Ms. Love situates the Slow Reading movement in the current state of our information environment. Today, we can do an Internet search for “what is the theme of the lottery by shirley jackson” and get the information WE THINK our teacher wants. In the past, analyzing a work required much more effort. You had to ask a friend or read Cliffs Notes or…read the story.

- Ms. Love compares reading to eating, uniting these most satisfying of human necessities.

Ms. Love did not originate this structure. Look what happens if I take a look at the most recent issue of The New Yorker:

- Here‘s a review of a new biography of Carl Van Vechten. See how Kelefa Sanneh begins the article in the same way as Ms. Love’s article?

- Here‘s a Sasha Frere-Jones profile of Beck. The same kind of opening.

- Here‘s Rebecca Mead’s profile of Neil deGrasse Tyson. The same kind of opening.

Ms. Love, who happens to be a great friend to creative writers and to cool people in general, offers us a trick we can use to manipulate our readers:

Difficulty slows readers down, and awkward wording is about as difficult as it gets… Once a passage begarnishes itself with odd or obsolete usages and syntactic constructions, we have to work harder to make the text coherent enough for us to move on. Even the most difficult words and constructions get easier with repeated exposure, however. Just as we can, over time, become accustomed to our bartender’s thick Irish brogue, we can adjust to difficult texts by changing our expectations about what we’ll encounter. The first time we read a sentence likeThe boy handed the candy bar drew a picture, it seems odd. But after reading a sentence like The boy driven to school drew a picture, the original isn’t quite as hard to get. Ordinarily, we’d assume that the boy had handed the candy bar to someone else. But because driven clues us in to the sentence’s reduced relative clause (in which the who was is dropped from The boy who was driven), we are able to interpret handed in the correct way. We have, in short, learned how to parse the sentence.

Most of the time, our goal as writers is to produce very clear prose for the reader. What’s the problem with that? As the article points out, readers may become too relaxed and may begin to gallop over your sentences instead of savoring them. You surely understand the concept. How long does it take you to read a Dan Brown novel? Not long; it’s a straightforward adventure made up of fairly straightforward sentences. How long does it take you to read James Joyce? The syntax of Mr. Joyce’s sentences can often be odd, forcing us to actually pay attention to the work.

Some of our scenes and some of our poetic lines should be very, very clear. Most of them, in fact. There are, however, times when it’s a good idea to throw up a “roadblock” or two. Look at suspense writing. I’m always fascinated how writers depict a first-person narrator being sucker punched or struck without warning. The narrative SHOULD be a little “unclear” in these places; the narrator isn’t clear as to what is going on, either.

Made-Up Example 1: I was walking down the street thinking of the dame who had just thrown me out. Some people don’t understand the threat they’re facing; women like her just don’t care. I pinch a nickel in my pocket to buy a Coke when a man sneaks up behind me and hits me with a billy club. I fall down and lose consciousness for a moment.

Made-Up Example 2: I was walking down the street thinking of the dame who had just thrown me out. Some people don’t understand the threat they’re facing; women like her just don’t care. I pinch a nickel in my pocket to buy a Coke.

That’s when the lug who’s been tailing be cracks me in the skull.

It hurts, but only in the second before I pass out.

Made-Up Example 3: I was walking down the street thinking of the dame who had just thrown me out. Some people don’t understand the threat they’re facing; women like her just don’t care. I pinch a nickel in my pocket to buy a Coke-

-CRACK-

I hear my skull fracture with the blow. Bread? Why do I smell bread?

Example 1 is very clear, but that may not be appropriate; the poor guy just got clocked in the head. By example 3, I have made the prose harder to understand. Doing so may knock the reader out of a rut that may have been comforting on the rest of the unwritten page, but is inappropriate when something crucial occurs.

What Should We Steal?

- Immerse your reader in a subject that may be complicated or unfamiliar. Sure, you may be starting a massive discussion about astrophysics and all of that, but our complicated universe is best introduced with a story and the assurance that you’re relaxing into the soft and warm grasp of a strong storyteller.

- Craft sentences that are harder to understand when appropriate. Friend, you’re the boss of the page. Slow your reader down if you feel the need or if it will create a helpful effect in your work.

Nonfiction

2012, Jessica Love, Ohio State, Openings, The American Scholar

Title of Work and its Form: “A Voice in the Night,” short story

Author: Steven Millhauser

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece made its debut in the December 10, 2012 issue of The New Yorker. As of this writing, the story is available online without a subscription. “A Voice in the Night” was also selected for Best American Short Stories 2013 and is featured in the anthology.

Bonuses: Very cool! Electric Literature has published Mr. Millhauser’s “Cathay” online for your enjoyment. (Presumably with the consent of the author.) Here is an interview Mr. Millhauser gave to Jim Shepard that was published in BOMB. Here is Mr. Milhauser’s Amazon page.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Mythological Retellings

Discussion:

This is a story about the fleeting nature of faith. (To me, at least.) It’s crucial to break down the structure. The story makes four trips through this series of perspectives:

I: Samuel. As in Samuel and Eli from the Bible. Each “I” section recounts a little more of the tale.

II: A seven-year-old boy who is growing up in Stratford, Connecticut. He is going through an interesting time in his life; the Sunday school teachers at the Jewish Community Center have told him the story of Samuel and Eli and he wants desperately to hear his own calling.

III: “The Author” is the seven-year-old boy at the age of sixty-eight. He seems to be preoccupied with memories of his youth. His mind and heart are not filled with the stories of the Bible, but with his own. The story ends as “The Author” reflects upon the Muse and the way in which stories can keep us up at night and dominate our lives while giving us something to live for.

Mr. Millhauser engages in an obvious (and perfectly wonderful) form of literary theft. The gentleman appropriated the story of Samuel and Eli from the Old Testament book of Samuel. There is, of course, no problem in retelling a story that has literally been rewritten for thousands of years. In doing so, Mr. Millhauser taps into the feelings the reader has for Judeo-Christian mythology, whatever they may be.

Mr. Millhauser certainly isn’t just stealing from those who conceived and passed down the stories from the Old Testament. The structure of “A Voice in the Night” mimics the relationship that people have with stories. (And mimics even more strongly the relationship religious folks have with their scriptural documents.) Without being too obvious about it, Mr. Millhauser is chronicling “the author’s” lifelong search for truth and his desire to understand what he is “meant” to do and to be.

How can we borrow from Mr. Millhauser’s borrowing of the Bible story? We can pinch a different timeless story. What about the story of the Prodigal Son? (Even though that one always drove me nuts.) Honestly, you can just go right to your copy of Bulfinch’s Mythology, open the book at random and plant your index finger onto a story ripe for adaptation or stealing. And if you don’t have a copy for some reason, you can read the book online.

- What if you blend a contemporary story with the star-crossed love of Pyramus and Thisbe? (Well, Shakespeare already did that, but you can, too.)

- What about crafting a father-son story that is influenced by that of Daedalus and Icarus?

- What could the Elysian Fields be like? (Aside from a great place to play baseball?)

Mr. Millhauser knows that he’s breaking a lot of rules and that his structure could alienate some of his readers. Why doesn’t he lose anyone? Why, because he makes the important parts as obvious as he can. Look at how Mr. Millhauser begins each of the first three sections:

- “The boy Samuel wakes in the dark. Something’s not right. Most commentators agree…” We learn that this section is about Samuel. After we read about “most commentators,” it’s clear that Mr. Millhauser’s narrator is referring to a mythological story of some sort. Even if you don’t know the specific Bible story, you still get the idea.

- “It’s a summer night in Stratford, Connecticut, 1950. The boy, seven years old, lies awake in his bed…” Mr. Millhauser doesn’t mess around. We know he’s jumped around in time and that the main character of the sections labeled “II” will be this boy. We’re not worried about what happened to Samuel; we know we’ll see him again if there’s another “I” section.

- “The Author is sixty-eight years old, in good health, most of his teeth, half his hair, not dead yet, though lately he hasn’t been sleeping well.” Great. It’s clear we’re onto a new protagonist for the “III” sections.

If Mr. Millhauser hadn’t held our hands a little bit, we may have found it difficult to understand the story’s dramatic present. (Such as it is.) When we deviate from the “standard conventions” of storytelling, we risk losing the reader. The more complicated the experiment, the greater the potential for confusion. It’s our responsibility as writers, therefore, to follow Mr. Millhauser’s lead and to provide sizable bread crumbs.

What Should We Steal?

- Make a conscious effort to turn an old story into one that is brand new. Oh, hey, check it out. Here are some more incredible stories just waiting to be stolen.

- Feel free to mess with your reader, so long as you keep the basics clear. The reader should only be disoriented in proper measure.

Short Story

2012, Best American 2013, Mythological Retellings, Steven Millhauser, The Bible, The New Yorker