A couple weeks ago, I was doing something that you should do. I was reading Dare Me, by Megan Abbott. The book is a fantastic…thriller/literary novel/New Adult novel that has gotten a great deal of well-deserved attention. Now, I was drawn in by Ms. Abbott’s beautifully drawn characters and her stellar use of language. I especially liked the way in which she added humor to leaven the sad story.

The prose, however, was sprinkled with little bits that drew the attention of my fountain pen nib. Ms. Abbott sprinkled in brand names from time to time. Take a look at some examples:

“I know she was out there in front of my house at 2:27, hunched over the steering wheel of her mother’s Miata.”

“Eyes on Tacy’s toned legs, which look like mini butterfingers, Beth shakes her head.”

“Flair strewn about, rolling empties of zero-carb rockstar and sugar-free monster, tampon wrappers and crushed goji berries.”

Ms. Abbott doesn’t include too many brand names in the book and I’m not entirely sure why some of them weren’t capitalized. (That’s not a criticism, really; Ms. Abbott is one of my favorite writers.)

Some writers embrace the inclusion of brand names in their work. After all, most of us refer to brand names all the time in our daily lives. We ask for a Pepsi instead of water. We order beer and wine by their brand names. When we don’t feel well, we ask our significant other to bring us a Tylenol or the bottle of Pepto Bismol. Brand names are part of our world, thanks to the fine work of all of the Don Drapers and Peggy Olsons out there. Including brand names in our fiction, then, could be seen as part of the responsibility we have to verisimilitude.

Brand names are also an opportunity for characterization and exposition. If you’re writing a story that takes place in the time when fountain pens were king, you could let the reader know that your character is well-off by giving him or her a Parker “51” instead of a Wearever Pennant. (The Pennant is a decent pen, but the “51” is sweet.)

However, this is a debate…

The use of brand names can also date a work. If memory serves, Stephen King includes a fair number of brand names in his work; young readers may stumble on what were commonplace references when Mr. King was in the heat of composition. Brand names could also be seen as a lazy shortcut that distracts from a work. You may decide for yourself that Ms. Abbott doesn’t gain anything by referring to Monster energy drink instead of just “energy drink.” You may believe that she violates Strunk and White’s first rule by including a word that could easily have been omitted. Deciding not to include brand names can also be a restriction that nudges us to increased creativity. Instead of a “Butterfinger,” could Ms. Abbott have included her own more powerful phrase?

What do you think? Do you use brand names in your work? When are they a good idea and when should you strike them with your red pencil?

Uncategorized

GWS Debate, Megan Abbott

Title of Work and its Form: The Three-Day Affair, novel

Author: Michael Kardos (on Twitter @michael_kardos)

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book was published by The Mysterious Press, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic. You can find it at your local independent bookstore. If you don’t know where your closest indie shop is, check here. I got my copy from The River’s End Bookstore in Oswego, NY. The book can also be ordered online, of course.

Bonuses: Here is what some smart guy thought about Mr. Kardos’s story, “Maximum Security.” (Oh, wait. That was me.) Here is Mr. Kardos’s interview with Brad Listi on his Other People podcast. Here is a very good review of the book from Spinetingler.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Will, Jeffrey, Evan and Nolan have been lucky enough to remain friends since their Princeton days. Sure, they don’t see each other very often. Getting together is hard; Jeffrey is a dot-com zillionaire, Evan is a hard-charging lawyer, Nolan is on his way to taking over Missouri politics and Will…well, Will is doing better. He witnessed his bass player get shot and killed in drive-by crossfire. He’s busy running a New Jersey music studio. No matter their busy schedules, the four men always make time for each other; they spend a week playing golf, eating steak and touching base.

Everything is great! Until the INCITING INCIDENT. (Or the turning point of Act One.) Jeffrey needs to get something from a convenience store, so they pull in. In a couple minutes, Jeffrey shoves the young clerk into the car and shouts, “Drive!” Will drives. This is a mystery/noiry-type book, so I don’t want to say too much more. Just read the book if you haven’t already; it’s great!

So, I don’t ordinarily like to create GWS essays about writers I’ve already featured. There are so many great storytellers out there and I want to feature as many of them as I can. On the other hand, I really liked the book and this is my site and I can do whatever I want. (I can’t really say that about too many other facets of my life.)

Mr. Kardos is probably quite justifiably proud of the favorable note The Three-Day Affair received from The New York Times Book Review. One of Ms. Stasio’s comments challenges me with respect to my experience with the book. “The plot,” she writes, “is original, if distinctly bizarre.” Now, I’m certainly not engaging in a respectful disagreement with someone like Ms. Stasio, someone with tremendous qualifications. I’m just not sure how I feel about her description of the plot, as the basic structure felt very familiar to me. In the prologue, we learn about the first-person narrator (Will) and what led him to move from New York City to the ‘burbs. The dramatic present picks up in Chapter 1. And Chapter 1 is pretty sweet. The four men care for each other deeply…they’re making good money…most of them have loving wives…Will is going to be able to start his record label…all is well.

Then boom-page 25 brings the kidnapping that starts the actual plot.

It’s certainly not a knock on Mr. Kardos or Ms. Stasio, but the book employs the tried-and-true structure for a noir/thriller/mystery.

- The first 100 pages of The Firm are great. Mitch is making money, he and Abby have a great relationship; all of his hard work is paying off. THEN THOSE TWO ATTORNEYS GET KILLED.

- In Strangers on a Train, Guy has his normal life. Sure, he’d like to ditch his wife, but things are looking up with the senator’s daughter. THEN BRUNO PROPOSES THE CRISS-CROSS MURDERS.

- Jimmy Stewart broke his leg, but things could be worse. After all, Grace Kelly is his girlfriend. THEN HE STARTS SEEING ALL OF THAT CRAZY STUFF OUT OF HIS REAR WINDOW.

- Marion Crane can’t afford to get married, but at least she has a boyfriend, a good job, a trusting boss…THEN THAT RICH GUY COMES IN AND PLOPS FORTY GRAND IN HER LAP.

- Will, Jeffrey, Evan and Nolan have their health, they ostensibly have a little money, they’re getting together for a week together. THEN JEFFREY SNAPS AND KIDNAPS THAT GIRL.

If you’ll notice, the THEN often happens around the Page 25 mark, just as the THEN often occurs around the MINUTE 15 or MINUTE 30 mark of a film. The book also mildly reminded me of the excellent 1998 film Very Bad Things. Here’s the trailer:

So five guys head to Vegas for a bachelor party. Then one of the guys accidentally kills the young lady who has come to “dance” for them. So the murder is an accident and the other four men are more complicit with each moment that passes. Should the guys protect their friend or go to the police? How do they handle their “105-pound” problem?

Like Very Bad Things, The Three-Day Affair does something wonderful. The characters are placed into a situation that tests their senses of morality. The stakes are constantly raised, of course, so what seemed okay two days ago (driving away from the store) becomes nothing in comparison with what seems okay in the present. Mr. Kardos’s book uses the changing dramatic situation to ask a number of important questions:

- How far would you go to help a friend?

- What’s more important? Your family or your good name?

- How do you get people to forget or to live with the bad things you’ve done to them?

- What’s the proper price of betrayal?

Mr. Kardos certainly doesn’t neglect his primary obligation; he tells us a rip-roaring story that you won’t forget for a while. But he does encourage the reader to consider deep and important thoughts. Will any of us, for example, be in the same situation as Mike McQueary, the man who walked in on Jerry Sandusky, well, raping a small boy? Probably not. (Thank goodness!) We will, however, be confronted with moral and ethical dilemmas that test us. What do we do in the moment? What do we do an hour later to atone for our failings in the moment already passed?

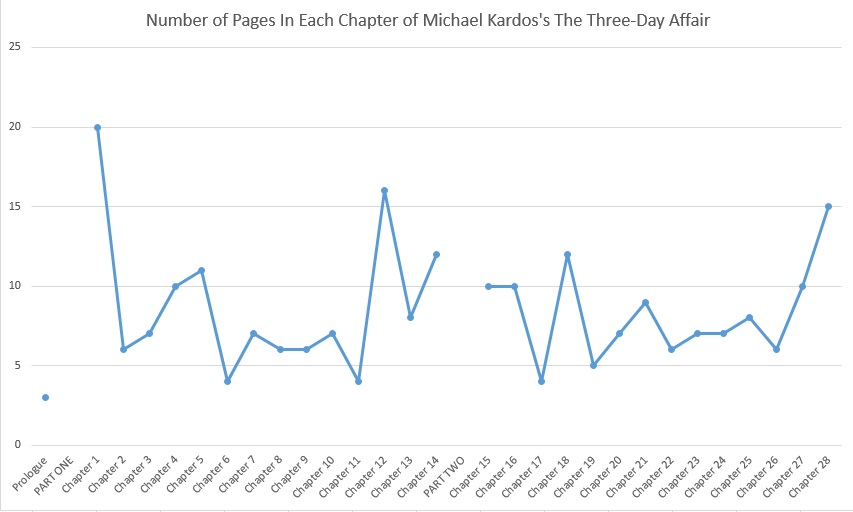

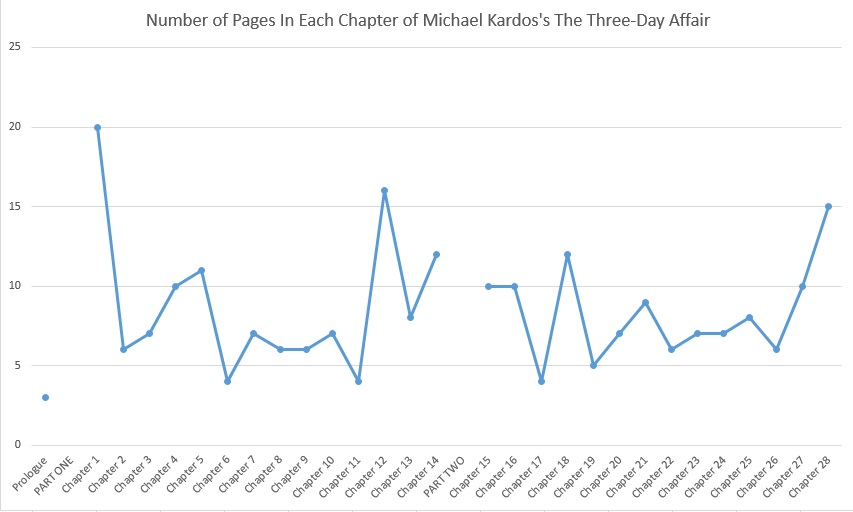

The world-class writer and teacher Erin McGraw would advise us, I think, to abandon our mistrust of numbers. (We are writers, after all.) So I’ve counted the length (in pages) of each of The Three-Day Affair‘s chapters.

Prologue: 3

PART ONE

Chapter 1: 7-26 (20)

Chapter 2: 27-32 (6)

Chapter 3: 33-39 (7)

Chapter 4: 40-49 (10)

Chapter 5: 50-60 (11)

Chapter 6: 61-64 (4)

Chapter 7: 65-71 (7)

Chapter 8: 72-77 (6)

Chapter 9: 78-83 (6)

Chapter 10: 84-90 (7)

Chapter 11: 91-94 (4)

Chapter 12: 95-110 (16)

Chapter 13: 111-117 (8)

Chapter 14: 118-129 (12)

PART TWO

Chapter 15: 133-142 (10)

Chapter 16: 143-152 (10)

Chapter 17: 153-156 (4)

Chapter 18: 157-168 (12)

Chapter 19: 169-173 (5)

Chapter 20: 174-180 (7)

Chapter 21: 181-189 (9)

Chapter 22: 190-195 (6)

Chapter 23: 196-202 (7)

Chapter 24: 203-209 (7)

Chapter 25: 210-217 (8)

Chapter 26: 218-223 (6)

Chapter 27: 224-233 (10)

Chapter 28: 234-248 (15)

And you know I love my literature-related charts:

What’s the point of all of this math-type stuff? Well, you can really see into Mr. Kardos’s thought process with regard to plotting. Look at the anomalies. There must be a reason Chapter 1 is so long, right? Well, he’s setting up the relationship between the men and painting a happy relaxed scene…so he can shake things up with Jeffrey kidnaps the girl.

Why is the last chapter so long in comparison? I’m going to be a bit vague, but the very beautifully written scene offers a motivation for the events of the whole book while complicating the narrative.

I should also point out that the line often looks like a roller coaster. Why would that be? You follow a fat Pope with a skinny Pope. The longer scenes tend to consist of high-octane suspense and the shorter scenes are a lot calmer connective scenes that prepare the next jolt.

What Should We Steal?

- Appropriate the structure of the classics. Look: Psycho worked in 1960. It works now and it will work a hundred years from now. You start out with a sunny and very normal day…then you bring in a lot of complications.

- Confront your reader with a series of deep moral dilemmas. Great drama comes from asking your audience to debate right and wrong.

- Consider the length of your chapters and scenes. Are you giving your reader enough time to recover from the gut punches you’re doling out?

Novel

2012, Megan Abbott, Michael Kardos, Narrative Structure, Noir, Ohio State, The Three-Day Affair

Title of Work and its Form: The End of Everything, novel

Author: Megan Abbott

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: At fine independent booksellers anywhere. Fine. Okay. The book can also be purchased on Amazon.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Description

Discussion:

Edgar Award-winning author Megan Abbott’s first novels are pulp fiction tomes that somehow capture the flavor of a time that passed decades before she was born. Her work is evolving in very interesting ways; this book certainly can’t be called a pulp novel and is not as much of a crime/thriller as it is simply a literary coming-of-age story. The first-person narrator of the book is thirteen-year-old Lizzie, a young woman who is lucky enough to have a friend like Evie Verver. The two grew up together and shared everything. Well, not everything. (There would be no book otherwise.) In very short order, Evie has been kidnapped by Harold Shaw, an insurance salesman who has a family of his own. Appropriately, Lizzie is the driving force behind the investigation that brings Evie home and learns an awful lot about herself, the Ververs and life itself.

Ms. Abbott took on a number of challenges by putting Lizzie in control. Although Lizzie-in-the-first-chapter is looking back on the book’s events with the wisdom granted by the passage of time, the rest of the book is told from the perspective of a very young woman who is still unversed in the ways of the world. On one hand, Lizzie cannot figure everything out too easily; on the other, Lizzie must be able to navigate the mysteries confronting her. Ms. Abbott makes the wise choice to simply trust her narrator and to give her the time she needs to realistically work through her many problems.

One technique Ms. Abbott used to create this kind of successful narrator was to vary the length of her sentences and amount of psychological insight contained within. Here’s the opening of third chapter:

The phone rings. It’s ten thirty at night. I’m brushing my teeth when it happens, and I hope it’s not my dad calling from California, calling from his apartment balcony, a sway in his voice, talking about the time we rented canoes at Old Pine Lake, or the time he built the swing set in the backyard, or other things I don’t really remember but that he does, always, when he’s had a second glass of wine.

The concrete details are contained in punchier sentences. Okay, so the phone rang when it was a little late. Not much analysis needed on Lizzie’s part, right? That long third sentence, however, does a great deal of work. The reader learns:

- Lizzie has some unresolved problems with her father

- The father feels some measure of regret for their current situation

- Lizzie remembers many of the good things he did

- Lizzie understands that these memories are often evoked by an extra drink

When all of the “raw data” is put together, the reader gains a deeper understanding of what Lizzie and her father mean to each other. This process also mimics the process by which we all mature; we absorb data, think about emotions and boom: we gain a little pearl of wisdom at some point. We can truly call ourselves adults when we have enough of those pearls. (I’m about three dozen short at the moment.)

People don’t arrive at epiphanies easily in real life and neither should Lizzie. Look at a some of Lizzie’s thoughts that arrive approximately three quarters through the book. (Don’t worry; it doesn’t really give much away.)

They’d been there, been there behind one of those clotty red doors, and done such things…and now gone. And now gone. And every night they stayed there when he left to get her food, did he lock her in – did he lock her in? How could he? But he would leave there and she would be there and would she wait, reader for her dinner, ready for him to click open the door and provide her with her dinner, like a jailer with no keys, with no locks, with no prisoner at all.

The first few sentences remind me of a gymnast working through his or her moves before a routine. The gymnast takes a step or two, twirls his or her arms and legs about a little and runs through the routine mentally. That last sentence? The gymnast (Lizzie’s thought) is off and running and nothing can get in the way. Narration such as this unites narrator and reader; both are trying to understand what is happening in the story and in the hearts of the characters living it. (Even better, the sentences are beautiful and musical and maintain dramatic momentum.)

What Should We Steal?

- Match your character’s lines and thoughts to his or her maturity level or mental state. Nineteen of the twenty chapters in The End of Everything are written from the perspective of a relatively bright thirteen-year-old woman. Ms. Abbott makes sure Lizzie always sounds and thinks like one. Lizzie asks a million questions as she tries to fill in her understanding of the world and of love and is even somewhat cryptic when relating information a young lady may not want to talk about…

- Construct your piece in a manner that serves the story you wish to tell. In different hands, The End of Everything would have been a far different book. While Ms. Abbott is very good at describing the “mystery/crime” elements, she devotes far more time to telling Lizzie’s story against the backdrop of the novel’s events. You have to decide which is most interesting to you: the explosion or its aftermath.

Novel

2011, Description, First-Person Narrator, Megan Abbott, Novel, The End of Everything