Trisha was a mother even before she had any kids. She had no choice, really. She had to grow up fast so she could protect her brother from their abusive mother and the procession of perverted boyfriends that went through their too-small home.

Rock Taylor was the Big Man on Campus, destined to accomplish big things in college football. He sees Trisha in the schoolyard one morning and it’s love at first sight…for him, at least.

The course of true love never does run smooth, of course, and Trisha has too many problems at home to even think about spending that valuable time and attention with Rock. Even though her heart rate increases every time Rock is around… Continue Reading

Novel

Abbi Glines, Simon Pulse, Young Adult

Cody and Meg were best friends before Meg went off to college at a private school in Tacoma, Washington. A little over a year later, Meg commits suicide by drinking industrial-strength cleaner. As you might expect, Cody wants to know what happened and why her friend chose to end her own life. Through the course of I Was Here, Cody undertakes a journey to come to grips with her friend’s choice and (obviously) reaches catharsis and a greater understanding of herself.

Gayle Forman is one of the superstars of YA, and for good reason. Her books confront big themes and are packed with big drama and give the reader big feels. Her book If I Stay was made into a major motion picture:

I Was Here is a well-written book, but it’s not a light, laff-a-minute novel. This is a good thing! We should all have well-balanced reading diets. The book is also a good example of contemporary YA, which is why it came to mind after a recent writers’ group meeting I attended.

A bright young man who has little experience as a writer, but is plugging away at a first novel (good for him!) described what he was writing. The young man had an interesting conceit and characters in mind, but, as he acknowledged, he was not sure about what would happen to them. All of that is just fine. If you are a beginning writer, the most important thing to do is put pen to paper. Over and over again.

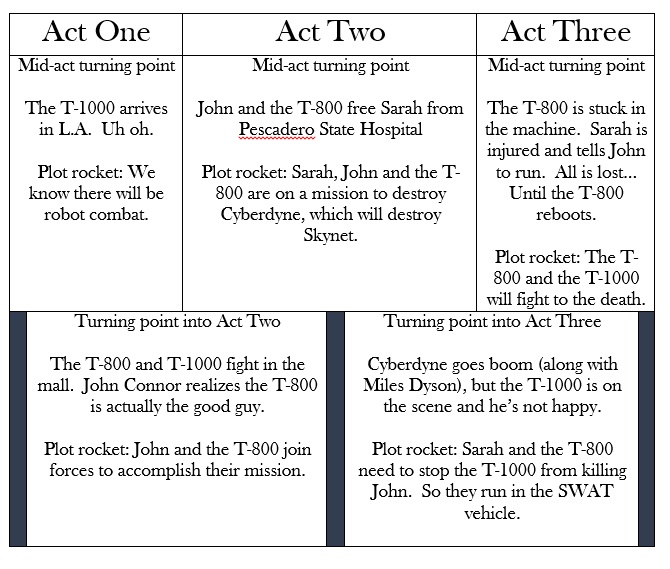

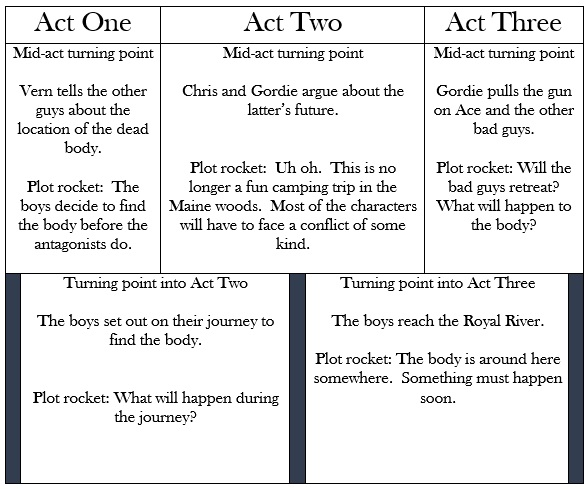

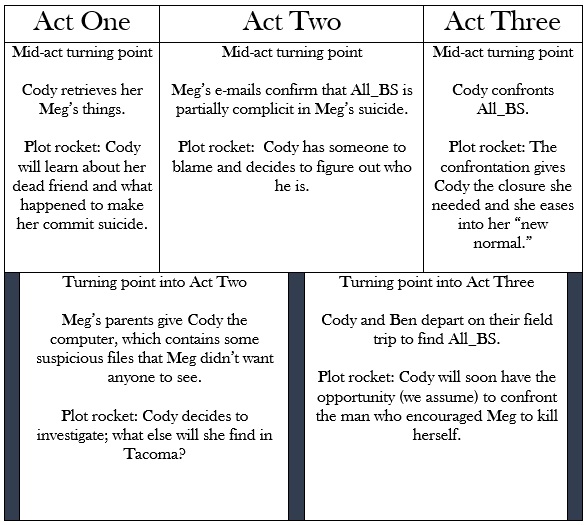

During the meeting, we all talked about the three-act dramatic structure that is so popular in screenwriting. Why is this structure popular? Because it works. Works that adhere to this paradigm have a beginning, middle and end and stuff happens in a logical and compelling fashion. What else do you want from a story? If you don’t know about the three-act structure, I advise you to immerse yourself in the works of Syd Field.

I animatedly helped the bright young man who was burning to write a YA novel think about how the vast majority of great novels and films adhere to the three-act structure. I hope to see him again and give him my marked-up copy of I Was Here, but why don’t I break down the three-act structure of the book for the benefit of all GWS readers?

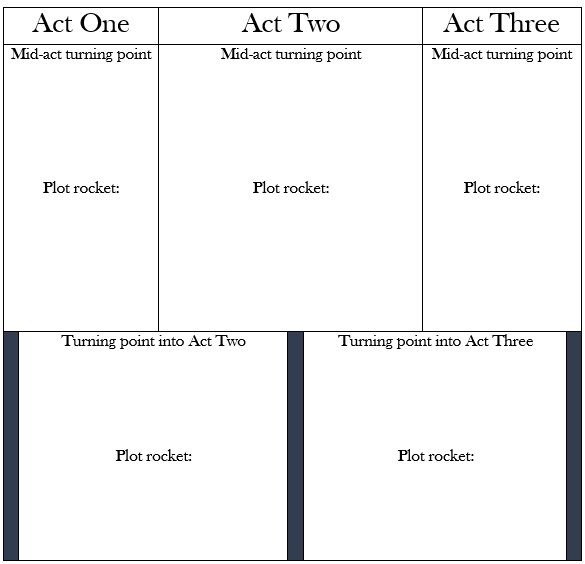

There are any number of ways to describe the three-act structure and I don’t want to steal someone else’s method, so I’ll sketch out my own. The point is that each story has three acts. The first establishes the world and pushes the protagonist on their journey. The second chronicles the protagonist’s journey as they make progress on their mission. The third ratchets the tension as the mission succeeds or fails. In the middle of each act is what I am calling a “plot rocket:” a turning point that changes the protagonist’s situation and keeps the plot moving.

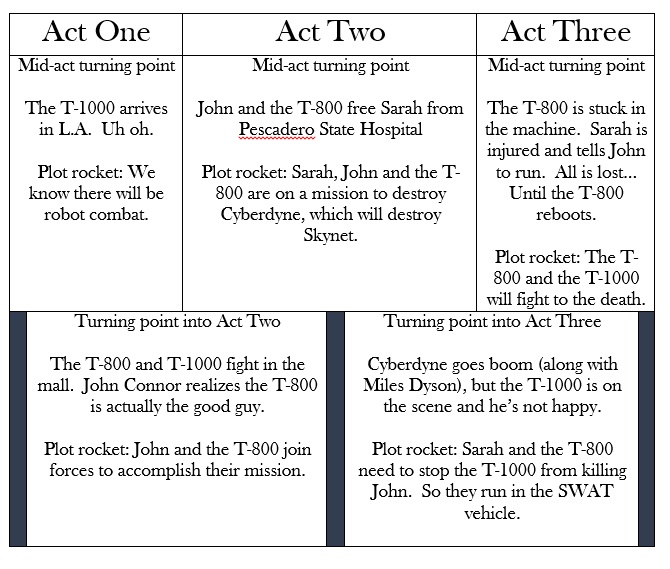

Have you seen Terminator 2: Judgment Day? If not, you are missing out. If nothing else, enjoy James Cameron’s rock-solid writing and direction. Here’s how the story breaks down:

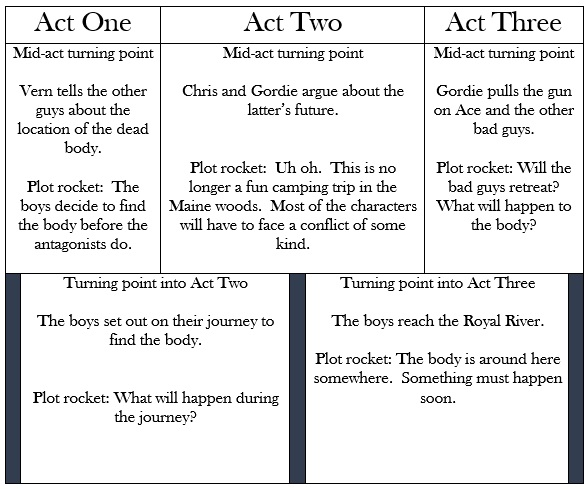

Want another one? You’ve probably seen Stand By Me, the film based upon Stephen King’s beautiful novella “The Body.” (Which could easily be considered a YA book.)

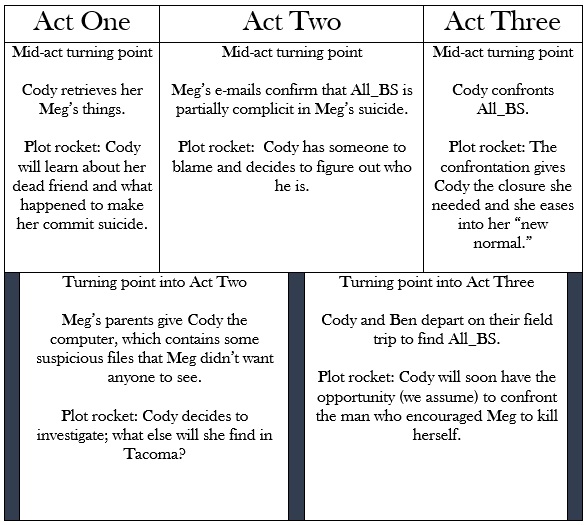

What about I Was Here? Well, here you go:

What’s the overall point? Ms. Forman employs the three-act structure to keep the story plugging along. Yes, Cody is very sad. She could linger for years in that sadness over the course of 2,000 pages. But that would not make for a very interesting book. No, Ms. Forman makes sure that things keep happening, things that are both driven by Cody’s actions and things that happen to her.

Not only should things HAPPEN in a story, but the ultimate point is that the protagonist’s situation should change. Their emotions should change. I don’t know if there’s such a thing as static drama. The three-act structure diagram reveals Cody’s emotional journey. Through the course of the book, she experiences shock, grief, anger…all of the emotions! (Particularly when she opens up to Ben a little bit.)

The young man who inspired this essay found the idea of breaking a story in this manner a little counterintuitive; that’s okay. Just about everything about writing involves practice. Next time you watch a movie or read a book, why not try to break it down into its three-act structure? Next time you are dreaming about your next story, think about where the plot point you have in mind may fit into the structure.

Here’s another way to think of it. If you are thinking, “I want to have a big fight between the the person on Earth who represents evil and one who represents good.” Okay, great. Guess what: that’s probably going to be the turning point in the middle of Act Three. Why? The idea as I expressed it is pretty heavy. It feels like a climax. If you have Luke Skywalker fight Darth Vader at the beginning of Act Two…you have a lot of movie left.

Let’s say you had a crazy idea about a person in prison who plays opera over the PA system for the other inmates to enjoy. Okay, great. But you need story before and after that. A guy playing opera over a PA system is not a punchy climax, really. You’ve seen The Shawshank Redemption; I just described the turning point of Act Two, according to Syd Field.

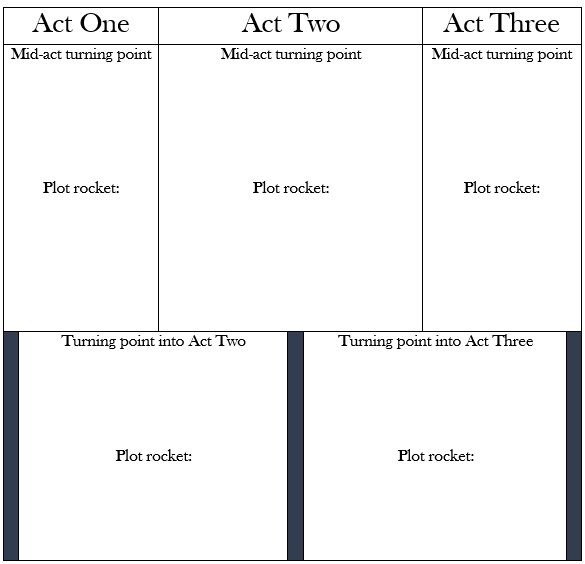

Here. I’ll even give you a blank version of the chart I made. Can you train yourself to break down the stories you enjoy by their crucial turning points? Ms. Forman can, and look what it did for her!

Novel

Gayle Forman, Penguin Speak, Young Adult

I don’t particularly believe in supernatural serendipity, though you are welcome to do so. I do, however, think that there are happy coincidences that can add joy to our lives if we are open enough to notice them. Buoyed by some good news a week or so ago, this pessimist drifted about town with no direction in mind. As you might expect, I ended up at the bookstore, as that is my natural habitat.

There was a reading/Q&A going on, so I quietly and politely went on about my browsing because I felt bad about not knowing about it in advance. I did, however, notice that the author was fun and a naturally engaging performer. As you could have guessed, my guilt over crashing the event (in a way) compelled me to pick up a copy of the author’s book and to join the throng of those having it signed. (As a terribly insecure writer, I have nightmares about holding a reading to which no one comes, even though I have never had a solo reading.)

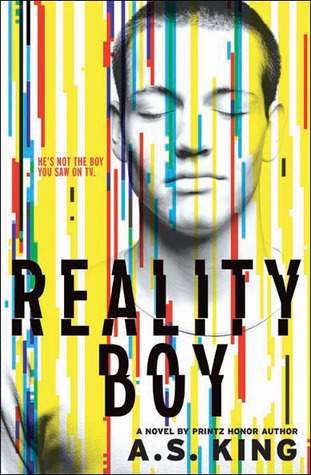

Long story short, the author is awesome and her book is even better. A.S. King is a big-time whose books are of interest to readers of all ages, but are specifically targeted at the Young Adult audience. Reality Boy is her 2013 novel about a young man named Gerald Faust (note the name…) whose parents signed the family up for one of those nanny reality shows when he was five. Blind to the abuse inflicted upon the family by his vile older sister, Tasha, little Gerald expresses himself in one of the only ways a little kid understands: he poops everywhere. Unfortunately, he will forever be known to the world at large as “The Crapper.”

So Gerald is angry. At his mother, at Tasha, at high school classmate jerks who treat him as though he’s still the five-year-old who left a turd in his mother’s shoe for the cameras to find. You know the overall arc of the rest: Gerald comes to terms with his anger, opens up to the right people, sees that he can make a new life for himself.

I’ve referred before to the near-infinite enthusiasm the Young Adult audience has for great works in the category; here’s a book trailer made by a fan:

And here’s a review from a cool young woman who should be able to convince you to buy the book if you haven’t already done so:

Onto the education. Ms. King is a very good writer and the book is very solid in terms of craft. One of the things I admire most about Reality Boy is that it is, as Ms. King describes her work, “gender neutral.” Now, does it make sense to say that all women will like a certain book? Of course not. However, some works, some kinds of subject matter, some tones are going to appeal more to one gender than the other. This is not necessarily a bad thing and people should read books from all genres and about all kinds of people. A.S. King turns the trick of making sure that Reality Boy has a little something for everyone. You have an angry young man whose anger is justified and who needs some love and understanding. You have an insecure young woman who feels she will never be able to escape the categorization thrust upon her by others. You have a dysfunctional family. Reality TV. Lots of emotions and lots of jokes. This is a book that cuts across all demographics, as is the case with all great literature.

I’m forever banging on about the need to #MakeMoreReaders. The statistics show that fewer men and boys are reading literature; Reality Boy is a satisfying book that doesn’t feel like homework. What else do you want in a book, really? More importantly: what is the proper balance in your work between “literary” and “entertaining?” What are our obligations to our audience? To my mind, Ms. King is the best of both worlds: her book satisfies the mind and heart.

In Reality Boy, Ms. King plays with the narrative a great deal. In addition to the good, old-fashioned first-person narration-(I did this, I did that…)-the narrative includes:

- Flashbacks to episodes of the nanny reality show in question

- Extended sections (that are not too extended) in which the protagonist essentially goes to his “happy place.”

- A letter from Gerald to the nanny

- Short chapters split by section headings that perfectly balance dialogue and action with the vast amount of introspection Gerlad must do

One reason Reality Boy succeeds so spectacularly is that Ms. King uses the kind of narration that satisfies the story’s needs. Some flashbacks can drag down a story. Please don’t tell John Irving, but I always skip over “The Pension Grillparzer” when I re-read The World According to Garp. It’s a thick stack of pages right in the middle of the narrative that only relates to the larger narrative in smarty-pants ways that are literary and beautiful, but pump the brakes on the story a bit. (Your mileage may vary.) When Ms. King sends Gerald to his happy place, the page or two add to the narrative. Same thing when the author describes another episode of the reality show.

Ms. King is certainly a great writer and a proud literary citizen; if you haven’t checked out any of her work, do consider ordering signed copies from her home indie bookstore, Aaron’s Books in Lititz, Pennsylvania. (That’s another way an author can be a good literary citizen!) And if you’re a YA fan who is surrounded by non-readers or grown-up readers who think they don’t like YA, put this book into their hands.

But don’t take my word for it…

See how much fun Ms. King is during this brief interview with Ariel Bissett, a wonderfully animated writer and reader?

Novel

A.S. King, Brown, Little, Young Adult

We all love Joyce Carol Oates for her beautiful and engaging work, for her steadfast advocacy of other writers, for her dedication to helping all of those who dare to turn thoughts into literature. Ms. Oates is also active on Twitter, yet another way in which she remains of prime relevance in our community.

Ms. Oates recently hit upon something that I think about a lot, even though it doesn’t apply to me in the least. As Shakespeare said through Cassio, our reputations are the immortal parts of ourselves and “what remains is bestial.” One reason that most of us bother to write at all is that we wish to ensure that some part of us may remain for many future generations. We hope that our stories and ideas may resonate hundreds of years from now, as Shakespeare’s do. Ms. Oates’s novels and stories will survive as long as humans crave stories (which is forever), but most of us will see our influence wane until it flickers and snuffs itself for lack of attention. (Out, out, brief candle!)

Ms. Oates reminded us of our temporary nature in a witty and Oatesian way, saying:

Ms. Oates name-checked some writers who have lost relevance in the canon over the past few decades:

Whatever the reasons, my heart went out to these writers, each of whom had the same dreams and goals and joys that are shared by every writer. They were also lucky enough to shape the community, for good and ill, through the generations of students who looked to them for wisdom and advice in the craft.

Other writers may be in the process of overwriting what they did during the twentieth century-such is the march of time-but let’s give a little attention to these writers, people who still have something to teach us.

To my shame, I had not previously read Howard Nemerov, but I am glad that Ms. Oates’s tweet did its job. Mr. Nemerov’s work, a nice sample of which can be found at the Poetry Foundation web site, is graceful and accessible in a way that demands a wider audience. A great deal of contemporary poetry, I am sad to say, seems contrived to confuse. Any time I have tried to introduce such work to young adults, they go away scratching their heads and checking their phones. When you show them a work such as Randall Jarrell’s “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” they go away thinking about the horrific nature of the ball turret gunner’s death and checking their phones.

Mr. Nemerov enjoyed working in forms and playing with meter and rhyme. (Another strike against him, it seems…) Judging from the sample I have enjoyed, Mr. Nemerov’s poems are relatable in the same way as those of Billy Collins: they often deal with parenting, aging and nature. These are subjects to which your non-writer (and perhaps non-reader) friends can relate, and Mr. Nemerov writes about them in a manner that these same friends can understand.

I suppose this is the first lesson we can take from Mr. Nemerov’s work. People love playing with language. They love contemplating where their life has gone and where it has been. Instead of cloaking our own profound thoughts in deliberately obtuse language, perhaps we should be more open to using meter and rhyme in a way that is accessible to those who have not yet earned their own MFA.

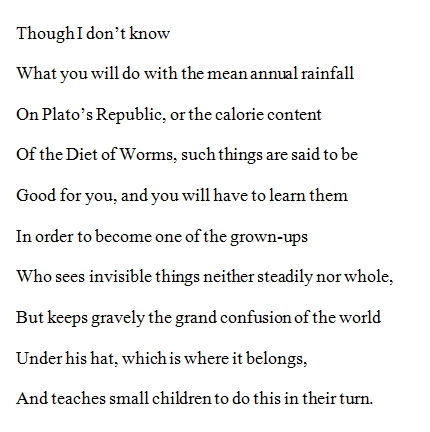

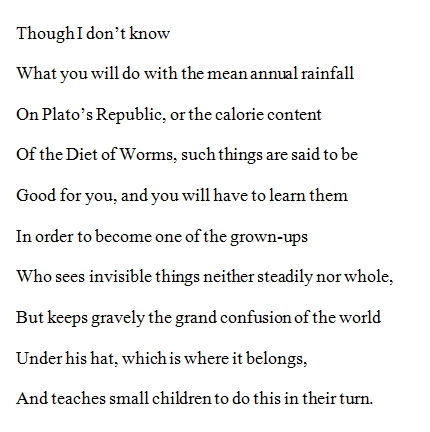

Let’s take a closer look at an extract from a poem called “To David, About His Education.”

What do we notice? Mr. Nemerov employs, in my view, a somewhat loose iambic pentameter in the poem. Unlike a more rigid example (“shall I comPARE thee TO a SUMmer’s DAY?”), the stressed and unstressed syllables are harder to identify. I wonder about the effect of this looser meter; are these lines more “accessible” to those who don’t yet realize they like poetry?

What do we notice? Mr. Nemerov employs, in my view, a somewhat loose iambic pentameter in the poem. Unlike a more rigid example (“shall I comPARE thee TO a SUMmer’s DAY?”), the stressed and unstressed syllables are harder to identify. I wonder about the effect of this looser meter; are these lines more “accessible” to those who don’t yet realize they like poetry?

You’ll also notice, for good and ill, that Mr. Nemerov’s use of meter forces him into making word choices. Look at that last line. Is “their” really necessary for us to understand what the poet means? I don’t believe so. Without that additional word, however, the meter breaks down. Where Mr. Nemerov is playful with the meter in much of the rest of the poem, he wisely ends it with a fairly solid line of blank verse:

and TEACHes small CHILdren to DO this IN their TURN.

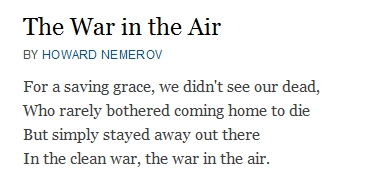

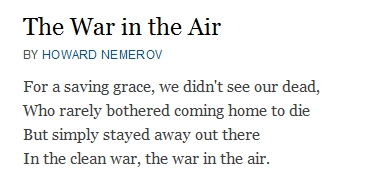

One of Mr. Nemerov’s more famous poems is “The War in the Air.” Here’s the first stanza:

It bears mentioning that Mr. Nemerov served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the U. S. Army Air Forces during World War II. Perhaps the first thing we notice is now Mr. Nemerov is playing with meter and rhyme. The first two lines of each stanza are cast in that “loose” iambic pentameter and the last two lines of each stanza rhyme.

It bears mentioning that Mr. Nemerov served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the U. S. Army Air Forces during World War II. Perhaps the first thing we notice is now Mr. Nemerov is playing with meter and rhyme. The first two lines of each stanza are cast in that “loose” iambic pentameter and the last two lines of each stanza rhyme.

Rhyme and meter are somewhat out of fashion today, but they will always be included in the poet’s toolbox. Why do I love that this poem follows some rules? The rhyme and meter contribute to the feeling of the poem. We can all agree that Mr. Nemerov saw some terrible sights during his time as a pilot and anyone who has spoken with a veteran knows that they took and still take what they did very seriously. The structure imposed by rhyme and meter, it seems to me, facilitate the kind of solemn reflection appropriate to the subject of the work.

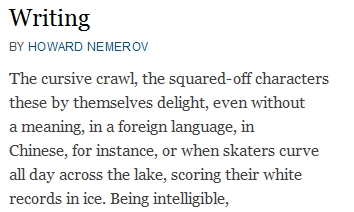

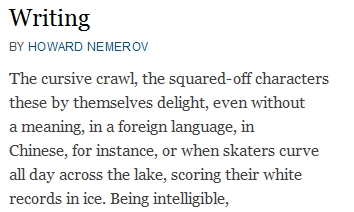

Like most writers, Mr. Nemerov reflected upon his avocation. Check out the beginning of his poem, “Writing”:

The first thing we notice is that the poet is adhering more strongly to the meter than was the case in the first two poems. Isn’t that image a beautiful one? Mr. Nemerov reminds us that everything about language is beautiful, including the very pen strokes we use to communicate our thoughts.

The first thing we notice is that the poet is adhering more strongly to the meter than was the case in the first two poems. Isn’t that image a beautiful one? Mr. Nemerov reminds us that everything about language is beautiful, including the very pen strokes we use to communicate our thoughts.

If nothing else, Mr. Nemerov deserves to be remembered for the decades of devotion that he gave to the writing community. Not only was he the Poet Laureate, empowered to spread the gospel of poetry far and wide, but he nurtured generations of poets as a teacher. So thank you, Ms. Oates, for reminding us of a writer whose name deserves to be on our tongues, if not for all time, at least a little longer.

Poem

Howard Nemerov, Joyce Carol Oates

Aggie Winchester dresses like a Goth and engages in modest rebellion with her best friend Sylvia. As the novel opens, in fact, she and Sylvia are about to skip school to get their eyebrows pierced. Aggie’s mother is the principal of her high school, which only complicates things further. The book has two inciting incidents, really: Sylvia reveals that she is pregnant and Aggie’s mother discloses that she has breast cancer.

Through the course of Lara Zielin‘s novel, young Aggie does quite a lot. She copes with her mother’s illness, her ex-boyfriend’s emotional manipulation, the heartbreak of bass fishing, the duplicity of the mainstream media and more. This coming-of-age story ends, of course, with Aggie coming of age and engaging in the identity formation that is one of the purposes of adolescence.

Ms. Zielin is obviously very much interested in her characters, but the book seems to be to be heavier on plot than a lot of books I have read recently. There’s a lot going on:

- Aggie’s tattered relationship with Neil

- Aggie’s strained relationship with Sylvia

- Sylvia’s pregnancy and her desire to have Ryan acknowledge it

- The health scare Aggie’s mother is enduring

- The prom king and queen election and its many…irregularities

- The bass fishing tournament

- The general population of St. Davis High already dislikes Aggie to some extent…then has reason to dislike her further

There are a lot of balls in the air in this novel! I find this interesting because I think we’re in a time when plot is slightly less in vogue in many quarters in favor of characterization and other implements in our writers’ toolbox. Here’s what is crucial about Ms. Zielin’s decision to go full speed ahead with plot: the plot is contrived in such a way that it emerges from and reflects upon her characters.

Think about it. Sylvia slept with Ryan and wasn’t vigilant about protection, which resulted in her pregnancy, which exacerbated her need to bring Ryan closer, which made her feel it necessary to do what she did with respect to the prom elections. The pregnancy also served to push Aggie away, which added to her stress levels and also inspired Aggie to do certain things. (I don’t want to give away the whole book!) Ms. Zielin’s characters are both citizens in and creators of the world they inhabit, as should be the case for most of our characters.

How do we know who we truly are? As you have surely heard before, character is who we are in the dark. The way we think and behave when we’re not being watched. Most people, of course, contrive their actions to mollify others, particularly young people like Aggie Winchester and her friends. Aggie’s journey, comprised of the many, many obstacles she faces, results in Aggie exposing more of her actions and thoughts to the light, dismissing what others might think of her.

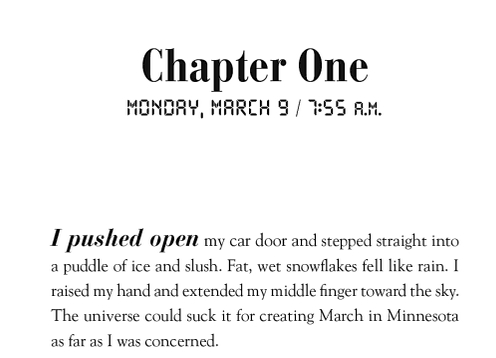

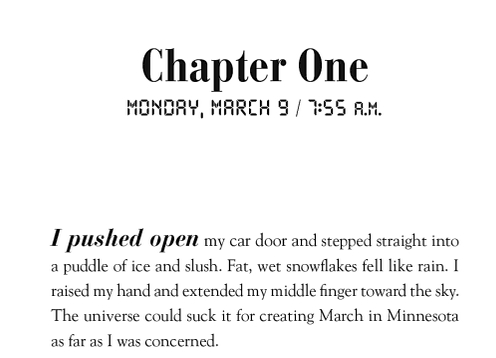

Ms. Zielin does something with the narrative that I think is interesting. Each chapter is time-stamped like so:

I find the technique interesting because I puzzled over the same issue as Ms. Zielin did when I wrote the YA book I recently completed. How do you depict the passage of time in a way that is simultaneously natural and obvious? A lot happens to and for Aggie between March 9 and May 2…how do you keep the focus on the events themselves and not what the calendar says? Sylvia is pregnant, which adds additional pressure to keep the calendar pages straight; that baby is a-coming out nine months after it was conceived and there are several well-documented and inviolable developmental steps in between. (You can’t have a mother showing when the baby is two months along.) The dates and times, I guess, are great for some readers, but I don’t think I needed them.

I find the technique interesting because I puzzled over the same issue as Ms. Zielin did when I wrote the YA book I recently completed. How do you depict the passage of time in a way that is simultaneously natural and obvious? A lot happens to and for Aggie between March 9 and May 2…how do you keep the focus on the events themselves and not what the calendar says? Sylvia is pregnant, which adds additional pressure to keep the calendar pages straight; that baby is a-coming out nine months after it was conceived and there are several well-documented and inviolable developmental steps in between. (You can’t have a mother showing when the baby is two months along.) The dates and times, I guess, are great for some readers, but I don’t think I needed them.

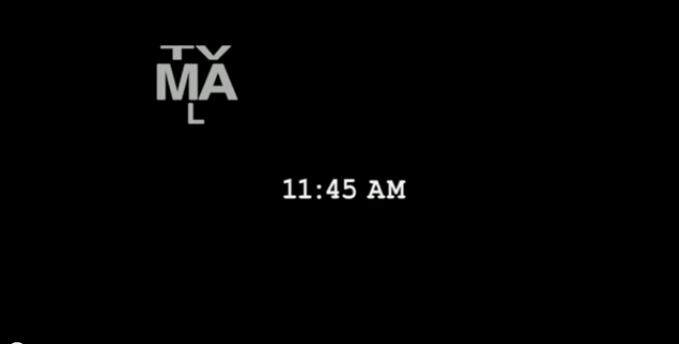

The times and dates do, however, function as a grounding device in the same manner as the ones used in It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia. Each episode of that show begins with title cards like these:

In this way, Ms. Zielin reminds the reader that her story is taking place in a world that the reader can recognize, even if the precise date and time don’t matter. Even though Aggie and her mother and Sylvia are going through an exceptional series of events, the kind of confluence of events to which few of us can relate, the chapter title timestamps are subliminal reminders that this world really isn’t that different from our own. Even if the reader skips over them, he or she doesn’t get lost in the narrative and they take precious little page space, so…why not?

In this way, Ms. Zielin reminds the reader that her story is taking place in a world that the reader can recognize, even if the precise date and time don’t matter. Even though Aggie and her mother and Sylvia are going through an exceptional series of events, the kind of confluence of events to which few of us can relate, the chapter title timestamps are subliminal reminders that this world really isn’t that different from our own. Even if the reader skips over them, he or she doesn’t get lost in the narrative and they take precious little page space, so…why not?

Just before the release of the book Ms. Zieling offered us an important lesson in how we deal with the manner in which our work is received. The person who reviewed The Implosion of Aggie Winchester for Kirkus didn’t particularly care for it. That’s okay, I suppose. We know what they say about critics. Writers (and agents and editors) are human, of course, and our hearts can’t talk our minds out of completely dismissing a negative review. Ms. Zielin, who seems like a fun and kind person, allowed her friend to turn the review into a heavy metal song. The lesson seems to be that writers have no way to avoid rejection and negativity, so we must do what we can to take it in stride.

Novel

Lara Zielin, Putnam, Young Adult

Aysel is sad and socially isolated because she feels her father’s shocking crime makes her a pariah. Her mother, step-father and step-sister love her dearly, but Aysel is simply depressed and needs help. Instead of speaking with a mental health professional, Aysel finds Smooth Passages, a web site where suicidal folks can support each other to complete the act. Aysel meets Roman, a young man who happens to live in a nearby town. The two young people set a date when they will commit self-slaughter.

Of course, the story doesn’t end there. Aysel and Roman build a friendship in the weeks before their departure date and open up to each other in ways they haven’t done with their families, friends and other loved ones. Jasmine Warga tells a beautiful and true story about the unhealthy ways in which we can deal with our pain and glorifies the safest road to happiness: feeling a connection with the rest of humanity.

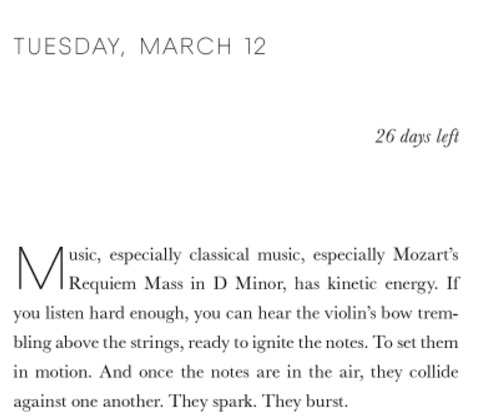

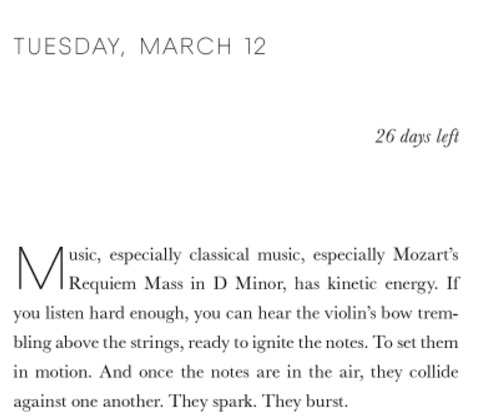

My Heart and Other Black Holes begins in a manner that is guaranteed to intrigue and immerses the reader in the narrative:

See what Ms. Warga did? She began the novel with a countdown. The reader may know nothing else about the book, but he or she is immediately aware that SOMETHING BIG IS GOING TO HAPPEN in 26 days. Want to know what that big thing is? You have to keep reading. (John Green employed a similar technique in Looking for Alaska…read for further detail.)

Another reason that countdowns are so effective is that they contextualize the ending of the story in the context of the protagonist’s life. In the case of My Heart and Other Black Holes, we learn that these are ostensibly the last 26 days of Aysel’s life. Ms. Warga makes it clear very quickly that Aysel is young and is physically healthy; the countdown forces the reader to consider a number of questions:

- Why does Aysel want to die?

- What is her family like?

- What’s the big source of shame she’s holding back?

- How long has she felt this way?

- What was her early childhood like?

Isn’t it amazing? All Ms. Warga did was type “26 days left” and the reader wants to know more and is devoting great thought to the young woman whose journey we will witness.

Beyond the countdown, Ms. Warga does a lot of great work releasing the exposition in the first few chapters. It’s a bit of a whirlwind, actually, but the author keeps it under control.

“26 days left” takes place at Aysel’s awful call center job. Ms. Warga establishes that:

- Aysel spends “a lot of time wondering what dying feels like.” We know she’s suicidal.

- Aysel frequently visits Smooth Passages, her “favorite website of the moment” and one dedicated to “people who want to die.”

- Aysel believes there’s nothing that can “fix her,” to lift her melancholy.

- Brian Jackson is an Olympic-bound athlete and the pride of his hometown, but is a replacement for Timothy Jackson, his brother. And everyone in town thinks of the older Jackson when they see Aysel because his death is her fault somehow through her father.

- Aysel is looking for a suicide partner to run away from her “black hole of a future” and this FrozenRobot chap is a good candidate…and he’s only fifteen minutes away.

- Aysel and FrozenRobot “have a date: April 7.”

That’s a lot of stuff, isn’t it? And it all comes in the first twelve pages. The next chapter (the first “25 days left”) is equally economical. We see Aysel during a day at school and are told that her father is the reason Timothy Jackson is dead. Once all of the exposition is out of the way, the author is allowed to zoom ahead with the plot. Sure, Ms. Warga has a lot more to explain and part of the joy of this book is unraveling the mysteries that rule Aysel’s and Roman’s lives, but the author shrewdly opens up the book to compensate for a protagonist whose mind is so closed. Unfortunately, Aysel simply can’t deviate too much from her intense depression early in the book. If she did, she might not come across as relentlessly suicidal. While Aysel still languishes in her sadness, the reader doesn’t get bored because she’s driving to the next town, meeting new people, meeting Roman’s mother, spending time wondering about Roman’s own sad mystery, getting ready for the Spring Carnival…phew! There’s a lot of change going on in the narrative, which keeps the book interesting because the protagonist’s mindset can’t change, at least not immediately.

This book is also great because it doesn’t waver in its commitment to its subject matter. This novel is about two young people who make a pact to commit suicide together. It must, by definition, be hardcore. Ms. Warga “keeps it real” by painting Aysel’s thoughts in a realistic manner. Look at some of the things the young woman says in the narration:

- “I can’t exactly tell Mr. Scott that I won’t be able to attend that summer program because I won’t be alive.”

- “I used to feel so devastated thinking about the length of days, about how time seems to stretch on forever, unforgiving and unchanging. And like John Berryman said, so boring. I wonder if this is how marathon runners feel once they reach the last mile; they know they can make it through the final stretch, so there’s no use in getting fatigued at this point.”

- “I stare at Mrs. Franklin, her smiling, eager-to-please face, and know that Roman and I are about to break her heart.”

- “But that would require me to talk in class, which would violate one of my personal rules. I don’t participate. Why? Because I’m fucking sad.”

Is it pleasant to think about a young man or woman (or a person of any age) making their quietus? Of course not. It’s blunt subject matter and Ms. Warga deals with it in a blunt fashion. If you’re dealing with an unpleasant subject-and dramatic tension often relies upon such-then you must deal with that subject in an honest fashion. Aysel is so depressed that she wants to die. The story is told from her first person perspective, so we need constant reminders of her welcomed mortality.

Ms. Warga’s book is a good example of the kind of Young Adult literature that has seized so much of my attention since a lot of “literary” work has left me so cold. While Ms. Warga offers some beautiful sentences, she also offers an inexorable plot. The book has a message (a very important one), but that message is never privileged over the need to tell the reader what is happening to Aysel and why.

As if you needed any more motivation to read the book (or to make YA a larger part of your reading diet), look at this fan-made trailer for the book. Sometimes I wish As could be more like YAs because the latter group expresses so much love for what they read.

Note: Ms. Warga includes some resources for those who may be experiencing suicidal ideation. In that spirit, I remind you that the National Suicide Prevention Hotline is available at 1-800-273-TALK.

Novel

Balzer + Bray, Jasmine Warga, Young Adult