Dear Chana Bloch:

I am writing to share my admiration for your work and, specifically, for

“The Little Ice Age.” It’s very kind of you to let people read the poem on your web site after its appearance in the Spring 2011 issue of Field. (Readers can also access the poem through EBSCO.) I also admire that you’ve posted an MP3 of yourself reading the poem; what a great way to help writers understand the difference between the written and spoken word.

You’ve done an awful lot of good for the poetry community and young writers are certainly advised to emulate the spirit in which you share your work and your thoughts. I happen to be a writing teacher (of far less renown, of course) and you must get a great satisfaction out of knowing how many thousands of writers have improved their craft because of your generosity.

As for your work, I love poems about history and science. I’ve written a few myself, though I don’t think any have been published. “The Little Ice Age” consists of two five-line stanzas. In the first, you paint the picture of what human existence was like during that event. In the second, you describe a beautiful and unintended consequence of that massive chill.

I love the way that you populate that first stanza with those two-word stings in the midst of the two longer sentences. Each of these phrases (but one) have the same construction: noun + verb.

Europe shivered

Rivers froze

crops failed

people chewed

people starved

This technique seems effective to me for at least a couple reasons. The “noun + verb” is very direct and very clear. Yes, these were the terrible consequences of the cooling across Europe. Alternate sentence constructions may not be as direct and convincing. Further, the “noun + verb” settles the matter. You’re letting us know that the poem is not part of a debate between climatologists; you’re just telling us what happened. Further still, the simple construction puts emphasis on those sad and powerful verbs. “Shivered,” “froze,” “failed,” “starved” …these are generally not happy verbs.

Goodness, and you use such a wonderful verb in the second stanza to describe the sound of a Stradivarius. Here is where you can hear a Stradivarius “cry” (albeit filtered through digital compression):

I admire the overall construction of the poem, as well. Two stanzas. Cause, then effect. The harshness of the climate resulted in the kinds of trees that Stradivarius needed to create his instruments. “The Little Ice Age” teaches scribblers such as myself how each stanza should contribute to the poem as a whole.

The baseball season is nearly upon us. A pitcher can’t think of each pitch as an isolated throw; he must decide what to throw based upon a vast number of factors. One of a pitchers big weapons is a change in velocity. Justin Verlander, for example, will blow a 100-mph fastball right past a batter, then drop an 81-mph changeup. The hitter doesn’t have a chance.

How does this relate to your poem? I admire the way that your first stanza sets up your second in the same way that a pitcher on my team causes a batter’s knees to “buckle.”

Thanks again for your poem and for all you have done for other writers of poetry and prose. I wish you the best in 2014 and beyond.

Ken.

Writing Craft Recap for My Kind Readers:

- Employ a simple “noun + verb” construction to solidify points that aren’t up for debate in your piece. This technique ensures your work will have brevity and allows you to steer focus to what really matters to you.

- Consider the function of your stanzas in the context of the work as a whole. Stanzas are to poems what paragraphs are to prose. Each of the smaller parts should contribute meaningfully to the operation of the larger machine. Follow a fastball with a slider or vice versa.

Poem

2011, Chana Bloch, Field, Ice Age, WriteAWriterDay

Title of Work and its Form: “Albert Arnold Gore,” short story

Author: Aubrey Hirsch (on Twitter @aubreyhirsch)

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in an online edition of American Short Fiction. You can read the story here.

Bonuses: Here is an interesting piece of science fiction that Ms. Hirsch published in Daily Science Fiction. Why not check out Ms. Hirsch’s first short story collection, Why We Never Talk About Sugar? You’ll also want to find out about her split chapbook. This Will He His Legacy was published by Lettered Streets Press. (You’ll also get pieces written by Alexis Pope!) Want to see a video interview Ms. Hirsch gave to PANK?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Public Figures

Discussion:

The story consists of three vignettes, each centered upon one of the Gore men. Albert Arnold Gore, Sr. was, of course, a Senator from Tennessee. Al Gore, Jr. was the Vice President under Clinton. Al Gore III is a business executive who, as of yet, has not entered the same public life as the earlier Al Gores. In the first vignette, Ms. Hirsch turns her focus to the philosophy by which Senior conducted himself as a father. In the second, Al Jr. is urged to enlist in the military in order to buffet Senior’s electoral hopes. In the final section, Junior teaches III-a young man who famously suffered a terrible car accident-how a man should fight and when.

Ms. Hirsch “steals” in glorious fashion in this piece. She is, of course, making use of the lives of public figures. The Gore family has been prominent in American politics for several decades. They have, to some extent, offered writers their identities. It’s perfectly acceptable, within reason, to transform these public figures into characters in our work. Sure, you probably can’t write a story in which you cast a real-life politician as a pederast or something equally abhorrent. (Think about what Law & Order does. We all know that the Monster of the Week is, say, Paula Deen. The writers, however, have renamed the Southern Lady who’s in trouble for using racist terminology. It’s not Paula Deen…it’s Maura Feen.)

By all means: write a short story about what Winston Churchill was doing while the Battle of Britain raged. Write a poem about William Henry Harrison coughing on his deathbed. We’re all curious as to what it’s like when Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt take their children to a casual dining restaurant. (Spoiler alert: I’m guessing a lot of Cheerios get crushed on the table and that they leave a big tip.)

Feel free to consult an attorney, of course, before you write your 500-page novel about Jessica Alba. It’s my understanding that public figures have a lower expectation of privacy than do private citizens. You’re well within your rights to fictionalize the life of a celebrity so long as you don’t stray into libel or slander or defamation of character. (I’m also under the impression that you have a lot more leeway with people who are long dead.) Ms. Hirsch is certainly well within her rights in “Albert Arnold Gore.” The story is an act of scene making based upon speculation derived from well-known facts.

It just so happens that I read a Roddy Doyle this morning in which his protagonist refused to provide his own name or those of his friends. This may be a logical move for the protagonist, but it could be a problem for a writer. After all, the reader needs to know which character is speaking and acting. Ms. Hirsch has a similar problem in “Albert Arnold Gore.” All of the characters in the story are named Albert Arnold Gore. Now, the three vignettes take place at very different times. The Albert born in the 1980s can’t be confused with the one who is being encouraged to enlist and go to Vietnam. Time just doesn’t work that way…yet. Someday. Still, there’s an awful lot of “Al” in this story. How does Ms. Hirsch manage to keep everything straight?

- Dates - The first sentence makes it clear that the section takes place in 1930. The third, we’re told, takes place in 1991.

- Generational Suffixes - There’s Senior and Junior and III. The suffixes keep things straight in the story, just as they do in real life.

- Clear Section Titles - Ms. Hirsch could have been a little less clear. Instead, she helps us out by naming each section after the Albert Arnold Gore whose POV is employed within.

There’s a bigger point to be made. It’s true that Ms. Hirsch is careful to keep the prose clear, but there’s an inherent and appropriate confusion in the story. Each character is named “Al.” Just as in real life, such a situation strips a little bit of individuality from each Al. Each of these men have made respectable lives for themselves, but they are inextricably linked by their names. Isn’t this the whole point of naming a kid for his or her mother or father or grandparent or family friend or dead aunt or uncle? When future Vice President Al Gore and his then-wife Tipper named their child Al Gore, they were imprinting slight expectations and some kind of identity onto the child. And why not? Al Gore I accomplished a great deal of good. Al Gore II was already in Congress when III came along. I’m betting that III may feel a little bit of pressure, but being III also has its advantages. The repetition of “Al” may give the reader a slight sense of disorientation, but it’s okay in this case because Ms. Hirsch is careful tokeep things straight.

What Should We Steal?

- Cast a public figure as your protagonist. What did President Bush (41) say to his aides after his mission in Iraq was accomplished? What did President Bush (43) say to his aides after his mission in Iraq was accomplished?

- Address possible sources of confusion in your work. There’s a reason why we avoid populating a story with characters whose names are Mary, Marilyn, Maribel, Marie, Marianne, Maryanne, Maria, Marielle, Moira, Mariah, Mareyea, Miriam, Marian, Molly, and Marty.

Short Story

2011, Al Gore, American Short Fiction, Aubrey Hirsch, Public Figures, Why Did He Wait Until After the Election to Showcase His Personality?

Title of Work and its Form: “Towing and Recovery,” short story

Author: Joe Oestreich (on Twitter @HitlessWonder)

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The short story debuted in Issue 32 of storySouth. You can read the piece here.

Bonuses: Here is the author’s Amazon page. Mr. Oestreich was on NPR. He’s living the Weekend Edition dream! Don’t you love seeing writers talk about their work? Here is an interview Mr. Oestreich gave during the 2013 Ohioana Book Festival:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Conflict

Discussion:

Geez, what a great story. Mike Dulaney drives a tow truck and spends his days pulling people out of the snow or cleaning up after accidents on the highway. He loves his wife Lisa, his stepdaughter Kimmie and his twins. The problem? Well, poor Mike has a lot of them. A couple years ago, Mike sorta snapped. After towing a vehicle from the scene of a deadly accident, he was weighed down by confusion and grief. Two young men-football players-were killed in the course of doing something dumb. The kind of thing he did when he was young. Mike drove the wrecker onto the high school football field and left it there. His subsequent job search didn’t result in very much…until he was offered a driving job by Phil, who also happens to be Kimmie’s biological father. Mike hates the guy, but needs the money. Another problem: Kimmie is thirteen. She’s starting to make the same mistakes that he made as a teenager; the same kind of mistakes that resulted in Lisa being pregnant at sixteen with Phil the Jerk’s child. Conflict everywhere! (In addition to beautiful writing.)

So, I love this story for a lot of reasons, but I really love how Mr. Oestreich set up the conflicts in the story. There’s a TON of exposition to release. (I was wondering if the story should be a novel.) Mr. Oestreich needs to communicate:

- How Mike and Lisa became a couple and how he feels about Phil using the sixteen-year-old version of his wife.

- The relationship between Mike and Kimmie. He loves her like a daughter, but blood is somehow thicker than…love.

- What Mike did two years ago to lose his job and why.

- The state of Mike’s marriage and whether or not the two are relating to each other in a healthy manner.

That’s not even all of it. As a result of the sixteen tons of necessary exposition, Mr. Oestreich simply didn’t have the option to describe the protagonist’s situation for two paragraphs before sliding into the dramatic present. So what did he do in the first scene? He introduced parallel conflicts that relate to the others:

- Mike is “waist-deep” under the crashed car he’s clearing from the road. (A reference to the Jeep he left in the middle of the football field.)

- Kimmie is nowhere to be found and Mike and Lisa are concerned. (A preparation for the father/stepfather/daughter “love” triangle that also evokes Mike’s resentment of his boss and, to a lesser extent, his wife.)

What is the effect of this technique? It reminds me of what a classical composer does in a symphony. Beethoven, for example, used the first three movements to layer in references to the themes and harmonies that would come to full flower in the Fourth Movement of his ninth symphony. (Why not listen to the whole thing? It will do you good and restore your faith in humanity.)

Would we love that beautiful fourth movement if we hadn’t just heard the themes in different contexts? Sure. The experience is deeper and more fulfilling, however, if we’re eased into the primary conflicts in the symphony or in the story.

For those of you who didn’t have a great music teacher early on, here’s an example from popular music. Look at how “I Want to Hold Your Hand” begins.

The dum-dum-DUUUMMMM, dum-dum-DUUUMMMM prefigures the the “I get high” figure in the song. This guitar growl is the emotional complication that makes the worksomething more than a boring “I love you” ditty. At first, this guitar part is a simple introduction, but…well…it turns out to represent “the feeling” one has after one “holds the hand” of the person he or she loves. (If you don’t know what I mean, ask your parents to tell you.)

Here’s another example. The Cher Lloyd song “Want U Back” introduces parallel conflict representative of the whole.

The song begins with Ms. Lloyd’s “frustrated grunt.” We hear the sound every four bars throughout. What is this sound? Anger? Well, it sounds like she’s angry about the situation as we hear the verse. Halfway through the song, however, we learn that the frustrated grunt has prepared us for an…alternate representation of what the grunt could mean. (Again, ask your parents.)

Mr. Oestreich is also really, really good at choosing details. Mike is already unhappy that he has to spend time with Phil and he’s clearly feeling the psychic weight of knowing that Kimmie is not his child and that a small part of Lisa will always be HIS. It’s perfectly dramatically appropriate that Kimmie has called her “real” dad to pick her up when Mike arrives to retrieve her. It also makes sense that a writer would allow Mike to see the phone and realize that Phil is ALWAYS AROUND. Mr. Oestreich, however, goes a step further and twists the knife by describing the caller ID on the phone.

Kimmie had countless options. She could have called him “Biological Dad.” “Sperm Donor.” “Father in the Eyes of the Law.” Kimmie labeled him “Daddy Phil.” I dunno if you agree, but I think this choice is as mean as it is perfect. “Daddy” suggests the child that Mike fears is disappearing as Kimmie grows. Having already called him “Mike,” the intimacy suggested by the name definitely explains what Mike does to the phone. (You wonder how Mike is classified on Kimmie’s phone…)

Here’s a small thing that is influenced, as always, by the great Lee K. Abbott. Lee emphasizes the importance of making sure you get the small details right in a story. If you make up a street name in a random real city, a reader who knows that municipality very well may be knocked out of the story as he wonders where the character is on the map. Our job as writers, of course, is to keep the emphasis on the drama. Now, I’m not criticizing Mr. Oestreich here, but I had a personal “drop out” moment that isn’t his fault. Early in the story, he mentions that Mike enjoys taking his family to Tiger Stadium to see the best baseball team ever take the field. Well, I just so happen to be a big Detroit Tiger fan.

In fact, here’s a picture that I took just after Todd Jones closed out the game against the Yankees (ew) on the day my grandfather was buried. (Does that seem weird to you? I don’t think so. I would rather have my friends and family enjoying our shared passions and thinking of me with joy instead of being miserable and mopey. I suppose I’ll find out for sure if I can get make any friends or accumulate family before I die.)

And here’s a picture I took of Tiger Stadium. I had the fortune to be able to spend some time with the old girl at Michigan and Trumbull.

Okay, I’ll get to my point. Mike takes the kids to Tiger Stadium, which became the Tigers’ spiritual home (as opposed to physical home) in 2000. Mike’s twins aren’t that old…the characters use cell phones…Kimmie the thirteen-year-old has a cell phone…Gah! During which year does the story take place?

Now, I don’t think that my unease is Mr. Oestreich’s fault. I’m just pointing out how we can unintentionally alienate a reader.

What Should We Steal?

- Ease the reader into complicated narratives by introducing your character in the middle of a situation that impacts the larger conflict that confronts them. The entire Godfather saga is a little bit complicated if you try to explain the whole thing at once. So begin the movie at the wedding that allows you to introduce all of the characters and their problems. Does the Don genuinely care about Bonasera’s problem with his daughter? Maybe not. But seeing Don Vito’s reaction prepares us to understand how much he loves his family and the lengths to which he will go for them.

- Break your characters’ hearts with tiny details. Dig deep to figure out what will hurt your poor protagonist the most, even down to the name under which his stepdaughter has saved bio-Dad’s cell phone number.

Short Story

2011, Conflict, Joe Oestreich, Ohio State, storySouth

Title of Work and its Form: “Head, perhaps of an angel,” poem

Author: Ida Stewart

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem was first published in the Spring/Summer 2011 issue of The Journal, Ohio State’s excellent lit mag. The kind people at The Journal have posted the poem online for your enjoyment. (I happen to know some of those people and they are indeed kind.)

Bonuses: Ms. Stewart published her first book of poetry in 2011. Why not consider purchasing Gloss from the folks at Perugia Press? If you’re in the Athens, Georgia area, why not ask Michael Stipe to give me a phone call and then buy the book from Avid Bookshop, a cool independent? (Gloss was even a staff pick!) Yes, you can also get the book from Amazon. Here is a review of Gloss that was written by Karen Pickell. Here is an interesting article about Ms. Stewart that was published in the UGA’s newspaper.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing:

Discussion:

Friends, this is a GWS first. Ordinarily, I begin each essay with a summary of the work. This time will be a little different. Look at how Ms. Stewart begins her poem:

Okay, she titled her poem and made the artistic choice not to capitalize some of the words. That’s fine. What about that next line? Now, I like to think I’m a well-educated guy and I like think to think that I wouldn’t embarrass myself on Jeopardy!…so long as I’m playing against Kardashians. (I would CRUSH it.) There are, however, many things I don’t know enough about:

- Mathematics that are more complicated than simple algebra

- Making money

- How to have a healthy relationship with a woman

- Writing stories good enough for all of the journals I love

- Art history

I also don’t happen to know about the Early Gothic Hall at the Cloisters. Here’s the dilemma on which we should focus:

Do I need to know about the Early Gothic Hall at The Cloisters in order to understand the poem? Or would knowing simply deepen my enjoyment of the poem?

The answer, of course, is that knowing enhances our enjoyment of the piece. Ms. Stewart understands a couple very important principles:

- A writer should not give his or her reader homework.

- It’s the writer’s job to do all of the work so the reader can have all of the fun.

(Number 1 is mine, but the second concept comes from the great Lee K. Abbott.) Now. If you’re like me, you want to erase some of your ignorance by learning about the Early Gothic Hall at The Cloisters. A part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters “is the only museum in the United Stated dedicated solely to the art and architecture of medieval Europe.” If you make the trek to Manhattan, you will be knocked out when confronted by the beauty that can be wrought by human hands.

So. Ms. Stewart’s poem gives you the opportunity to reflect upon a work from The Cloisters, but doesn’t require you to do so.

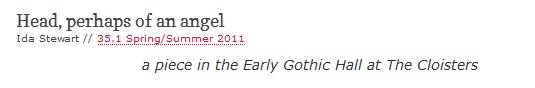

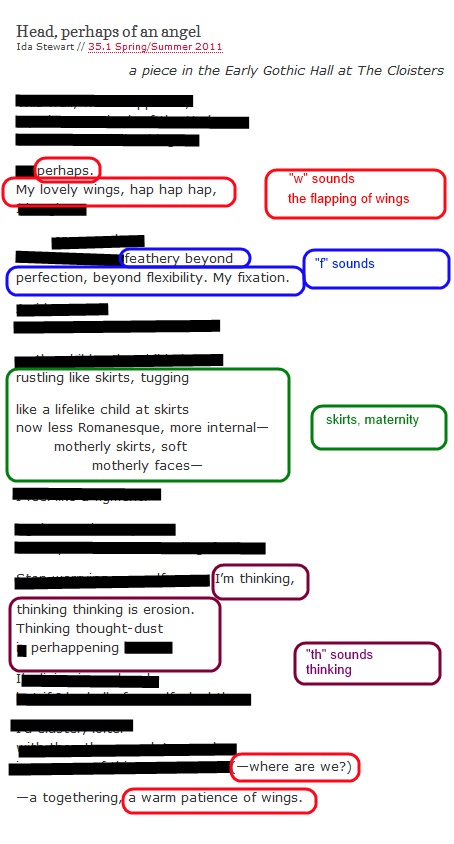

Okay, to the poem itself. I think one of the things that sets great poets apart from the mediocre ones like me is an understanding of how to structure their work. Poetry isn’t just a scattershot jumble of words; there’s meaning behind each of the million choices a poet makes. Look how Ms. Stewart structured her poem:

The poem consists of a few different sections that, when combined, make Ms. Stewart’s ultimate point. Isn’t this what it’s like to walk through a museum or gallery? You have similar experiences (looking at paintings and sculptures) that are also very different because of the range of reactions you have to the art. The author guides the reader through different sounds and concepts, just as a museum guide can take a guest through different exhibits. Best of all, the poems ends as it begins, just as you emerge from the museum to the world you inhabited before.

It can sometimes be difficult to employ onomatopoeia in an unanticipated and felicitous manner. It’s often tempting to simply say that the gun went “BANG” or to describe the “CRACK” of the bat. Look what Ms. Stewart did. Not only does she describe the flapping of a bird’s wings with an unexpected “hap hap hap,” but she has also tied the sound to the “perhaps” in the previous line. Ms. Stewart’s ingenuity makes the whole of the poem more cohesive and sets it apart from other poetic depictions of an featured nature.

What Should We Steal?

- Never give your audience homework and remember: it’s the writer’s job to do all of the work so the reader can have all of the fun.

- Lend structure to your work, even if the scaffolding isn’t immediately obvious to the reader (or to you). As the writer, you are the invisible hand at work behind the scenes. Take control!

- Employ onomatopoeia that is both unexpected and performs additional function. How else can you describe a bird’s song? Tweet tweet and chirp chirp are taken.

Poem

2011, Ida Stewart, Ohio State, The Journal

Title of Work and its Form: “The Hare’s Mask,” short story

Author: Mark Slouka

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was published in the January 2011 issue of Harper’s. If you are a subscriber, you can read the story here. Heidi Pitlor and Geraldine Brooks later selected the story for Best American Short Stories 2011 and included it in the anthology. (A book we should all have anyway. =) )

Bonuses: Mr. Slouka published a great essay about the university in the September 2009 issue of Harper’s that describes the state of the humanities in higher education. The Paris Review has been kind enough to publish a Slouka story online. Here is “Crossing.” Here is an interview Mr. Slouka did with Powell’s.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Opening a Story

Discussion:

This powerful first person story is told by a grown man who misses his father terribly. The first couple pages is devoted to a sweet description of the narrator’s father tying a fishing fly.

Mr. Slouka then slides into the primary narrative of the piece. During his Czechoslovakian childhood (future band name?) he narrator’s father was responsible for tending to the rabbits in the hutch. The father’s family hid a fleeing Jew in the rabbit hutch for nine days as the Nazis made their way through the area. The father was responsible for bringing the man food and a bucket for bodily waste. Speaking of food, the number of rabbits in the hutch dwindled very fast. Before long, the narrator’s father had to make a choice between two of his favorites: not an easy thing to do for a young child. Between description of the events of wartime Czechoslovakia are parts of the narrator’s own childhood. His sister wanted a rabbit desperately, not knowing the rabbit-related sadness her father had known. In response, the narrator calls the rabbit “Blank” and tries to work, in a childlike manner, through the kind of sadness his father successfully prevented him from feeling.

One of the big lessons that I learned from Lee K. Abbott is to be vigilant in considering where your story really starts. Like all writers, Mr. Slouka had a choice to make. The first four sections of “The Hare’s Mask” could each serve as the opening of the story:

- “Odd how I miss his voice…” - Establishes the POV and the son’s desire to protect the father and the hint that the father might have had some childhood trauma.

- “He used to tie his own trout flies…” - Establishes the POV and the kindness of the father and the fishing fly thing and hints toward the father’s childhood trauma.

- “I don’t know how old I was…” - Establishes the POV and the importance of the father and the man’s possible childhood trauma.

- “It began with the hare’s mask…” Establishes the POV and the fishing fly thing before rolling right into the “full story” of what happened in Czechoslovakia.

What is the effect of the choice Mr. Slouka made? I think that including #1 first was wise because a great deal of story takes place during the narrator’s childhood anti-rabbit campaign. #1 takes place in the dramatic present , relates a story from the narrator’s past and establishes that a great deal of “The Hare’s Mask” will likely relate events that happened “during the war.”

The important thing to remember is that each beginning would offer a slightly different shape to the story. Not necessarily better or worse, I suppose, but just different. When you dive back into a manuscript to do your second draft, try to figure out if the first paragraph should really be the opening of your tale.

So “The Hare’s Mask” centers upon a boy who has an emotional connection to rabbits. Guess what happens when he has his own children…one of them wants a rabbit! Drama and comedy often come out of our personal peccadilloes. In a way, this is a variation on Chekhov’s gun. (The writing concept that implies that if there’s a gun on stage in Act I, that gun better be fired by the end of the play.)

Mr. Slouka very wisely made all of the conflicts in the story streamlined and natural. The narrator has a conflict with his sister: she wants a rabbit and he wants to protect his father. The father had an internal conflict (and an external one with his hungry family): He didn’t want to kill the rabbits, but other people wanted to eat. What kicked off all of these conflicts? Nazis being unpleasant (to say the least). The conflict in the story can all be traced back to the Nazis’ desire for Lebensraum. All of the drama is related and all of it subsequently makes sense.

What Should We Steal?

- Decide when your story REALLY starts. Every narrative has numerous possible points of entry. Which is best for the story you want to tell?

- Allow conflict to emerge from your characters and what happens to them. Your character is sad because he had to kill rabbits as a kid? Guess what…that character’s kid is going to want a rabbit. Your character doesn’t like people in a certain demographic? Guess what…they’re going to end up in a job interview facing a person of that demographic.

Short Story

2011, Best American 2011, Harper's Magazine, Mark Slouka, Opening a Story

Title of Work and its Form: “Tenth of December,” short story

Author: George Saunders

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story premiered in the October 31, 2011 issue of The New Yorker. You can read the story here. You can also find the story in the 2012 anthology of Best American Short Stories. The story headlines Mr. Saunders’s book Tenth of December. Why not pick it up from an independent bookseller such as Reno, Nevada’s Grassroots Books? (They seem very cool!)

Bonuses: Here is an interview in which Mr. Saunders discusses “Tenth of December.” Here is what blogger Karen Carlson thought about the story. (She makes interesting points about the POV and describes her understandable “struggle” with the story.) Here is Mr. Saunders’s page at This American Life. (You know you love This American Life.) Yes, Mr. Saunders is a very influential man.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

Robin is a slightly chubby schoolboy. Don is a middle-aged father who is suffering from cancer and is determined to commit suicide. How are these two unrelated characters related? One of those good, old-fashioned twists of fate. Don leaves his coat on a chair to help the authorities locate his body. Unfortunately, Robin decides to try and do a good deed and bring it to him. Robin takes a shortcut across a frozen pond. What happens when Robin falls into the freezing water?

Mr. Saunders’s story is a very interesting study. The narrator is a very close third person alternating between Robin and Don. The narrator absorbs each character’s idiosyncracies; Robin is pretending he is talking to a girl he likes and that he is surrounded by supernatural woodland creatures and Don’s brain is failing because of illness. I noticed that the story “threw” Ms. Carlson at first; the same thing happened to me, but in a different way. For a few pages, I was under the impression that the “Nethers” were real. (You know, short story real.) Mr. Saunders describes the world of the Nethers and what they look like and how they act and so on, going into a great deal of depth. Very quickly, however, I was right on track. Mr. Saunders had to do what he did in order to immerse the reader in Robin’s brain and to establish the close POV that works so well in the story. What lesson can we take away from this? A reminder that the first couple pages of your piece establish the unique world in which your characters live. Readers are willing to follow you ANYWHERE, so long as you make the ride smooth.

Think about Kafka’s Metamorphosis. Remember the first sentence?

One morning, as Gregor Samsa was waking up from anxious dreams, he discovered that in his bed he had been changed into a monstrous verminous bug.

Kafka (like Saunders) doesn’t mess around when establishing his conceit. Guess what, Kafka seems to say. This is a world in which Gregor Samsa turned into a giant bug. Deal with it. Saunders has the same strong kind of declaration: Hey, reader. You’re in the head of a young boy who likes a girl named Suzanne and has a great imagination.

The choice to craft the story from the separated points of view of two different characters gives Mr. Saunders at least two big bonuses:

- Mr. Saunders can offer, very gracefully, two different accounts of the same event. And why not? Each POV character is experiencing them on their own terms.

- Mr. Saunders can allow the characters the same kind of first-person confessional without allowing the other character to get in the way. We don’t need Don’s commentary on Robin’s crush on Suzanne and Robin shouldn’t be allowed to give us his commentary as Don does what he can to keep the kid warm.

As we can all attest, coming up with titles is a pain. How did Mr. Saunders do it? “Tenth of December” is great because even if it’s not the date on which the story takes place, it evokes a time in which the weather (in the Northeast) is cold, but not cold enough for there to be ten feet of ice on the local lake. I also get a Tropic of Cancer vibe from the title. (Ooh, and that’s one of Don’s problems. Cool.) So here’s another title formula:

TITLE FORMULA #8675309: The date on which the story takes place, or a date on which the story COULD take place.

What Should We Steal?

- Think of your first few pages as orientation for your reader. Before you get in a ride in an amusement park, you spend 45 minutes in the queue, learning about the “world” of the attraction. (Your stories are attractions too, right?)

- Employ parallel and severely limited third-person points of view. You gain contrast and a kind of intimacy.

- TITLE FORMULA #8675309: The date on which the story takes place, or a date on which the story COULD take place.

Short Story

2011, Best American 2012, George Saunders, Point of View, The New Yorker

Title of Work and its Form: “Beautiful Monsters,” short story

Author: Eric Puchner

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story first appeared in Issue 50 of Tin House. The story subsequently appeared in the 2012 editions Best American Short Stories and Best American Nonrequired Reading.

Bonuses: Here is what Karen Carlson thought of the story. (I love that she brought Asimov, Ellison and Heinlein into the discussion.) Here is an interview Mr. Puchner did with The Rumpus. Here is a very good GQ piece Mr. Puchner wrote about his father. (I even remember reading it in the magazine. Good for me!)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: World Creation

Discussion:

Imagine a world without adults. A boy and a girl, two Perennials who will never grow up, have made a home together. Inciting incident: A man, an honest-to-goodness man, shows up outside the kids’ home. The authorities apprehend these beautiful monsters, these Senescents, but the boy and girl take the man in. The ticking clock in the story is the man’s injury; gangrene (or something like it) is turning his leg into a festering mess. The boy and girl have differing attitudes toward the man; the former seems to enjoy having some kind of father (at first), and the girl seems very confused by the attention. The man teaches the children how to play like, well, real children and shares his memories with the boy and girl. Sadly, all good things must end. The boy somewhat changes his opinion of the stand-in father and infection lays the man low as sirens approach. The last paragraph takes an appropriate turn into the abstract.

Anyone who reads the story will likely notice the speed and deceptive ease with which Mr. Puchner establishes the world of the story. Readers are willing to follow a writer anywhere, so long as they are guided well and enough. Look how Mr. Puchner lays in the clues immediately.

- The character is called “the boy” repeatedly. No name. His sister is referred to by title and by pronoun. Not only can we gather that the boy is a main character (you can’t have twenty characters called “the boy”), but the generic names create a kind of discomfort

- In the fourth sentence: “The boy has never seen a grown man in real life, only in books…” Mr. Puchner makes his conceit a little clearer. No grownups in this world. (Well, not out and about.)

- The man is described in the title and the first paragraph as a monster. He is “bearded and tall as a shadow” with hands that are “huge, grotesque, as clumsy as crabs.” The reader understands what a strange experience this is for the children.

- Early dialogue: “He must have wandered away from the woods.” Okay, so the grownups exist outside of mainstream society.

A writer must decide which mysteries he or she will maintain. And you can’t have too many in your work or your reader will be confused.

I love stories that contain ticking time bombs of some sort. A bad guy or bad girl breaks into a bank and gives the police an hour to give him or her what she wants. Something is going to happen after an hour. There’s a great Dragnet episode in which a bad guy has put a bomb in a school that will detonate at a specific time; Friday and Gannon MUST GET THE LOCATION. Ticking time bombs, whether literal or not, imbue a story with inherent drama. The reader has an idea of what might happen, but has no idea about how the specifics will play out. In “Beautiful Monsters,” the gangrenous leg is getting worse and worse. The reader is left to wonder: is the man going to die? Is the man going to try and get help at the hospital? Will the boy saw the man’s leg off? We don’t know for sure, but SOMETHING is going to happen. A ticking time bomb can also reinforce the fact that the writer is in control and knows what he or she is doing.

What Should We Steal?

- Establish the strangeness of your unique world clearly and early. One or two mysteries are fine; too many will confuse your reader.

- Give your story a countdown. A pregnant woman is going to have that baby nine months or so after conception. (Hopefully!) That story has a discernible end, complete with inherent drama.

Short Story

2011, Best American 2012, Eric Puchner, Tin House, World Creation

Title of Work and its Form: Emily, Alone, novel

Author: Stewart O’Nan (on Twitter @stewartonan)

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book can be purchased at all fine bookstores. Why not give some business to a local retailer, such as Oswego, NY’s The River’s End Bookstore? You can also buy the book online from sites such as Powell’s.

Bonuses: I am healthily jealous of Mr. O’Nan for countless reasons. He wrote a book with Stephen King…and it was about baseball. Faithful is excellent and anyone who loves sports can relate to it. (I’m a Tiger fan and I loved it.) I also enjoyed the very short but very powerful Last Night at the Lobster. Here is an NYT piece in which Mr. O’Nan discusses the book. Here is a Washington Post review of Emily, Alone.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Exposition

Discussion:

Books bring us many blessings. In addition to the joy of “living” with Emily for a few hours, Mr. O’Nan removed me from the stress and inconvenience of a flat tire. I heard the dreaded thumpthumpthumpthump and knew that something was wrong and immediately pulled into a safe area between houses/apartment buildings. I hasten to point out that I tried to put the spare on myself, but the tire wasn’t coming off. I didn’t want to kick the tire too hard, sending the car off the jack and rolling into the street, so I called for roadside service…and waited.

And waited.

I don’t really respond well to these kinds of problems; they bum me out a lot more than they should. Thankfully, I am the kind of guy who has a ton of books in his car. Believe it or not, I waited so long for roadside assistance that I was able to read the whole book.

And what a book it is. Emily Maxwell is a widow who is in that somewhat sad state of life. Her children are grown and have their own children. Her circle of friends is decreasing steadily. She is surrounded with reminders of her old life. There is certainly plenty of joy. Emily sees her mildly disappointing kids and her grandchildren on occasion. Living in the same place for so many decades makes a trip to the breakfast place an opportunity to see many familiar faces. The book begins as Emily and her sister-in-law Arlene are off to have some breakfast—with a coupon, natch. The inciting incident of the novel occurs when Arlene has a mild stroke, collapsing beside the buffet.

The rest of the book represents the craft lesson I’d like to discuss. A lot happens in the book…and it doesn’t. Emily thinks about giving away the matched luggage her husband Henry bought a long time ago. Emily considers (in a pleasant way) her granddaughter’s lesbianism. Emily wonders whether or not she should hide the ancient liquor before her daughter Margaret visits. A hit-and-run driver collides with the giant car that Henry loved in the middle of the night.

Is this a thrill-a-minute book? Yes and no. Mr. O’Nan has the bravery to tell a thrilling internal story about an interesting woman. I don’t know if you have the same tendency, but I always feel the need to MAKE THINGS HAPPEN in stories. I’m not saying that there must always be explosions or kidnappings or alien invasions in my work, but Mr. O’Nan offers a great reminder that story is also about internal conflict and the lives of normal people.

One of the metaphors that I use for storytelling is this:

When the reader begins a story or novel, he or she should feel as though the writer has flipped a chair backwards, straddled it and said, “Okay, I have a great story to tell you. Here we go.”

Mr. O’Nan certainly makes it clear that he’s going to tell you a great story, but I think he is saying something different after flipping the chair:

“You may remember Emily from one of my previous books. Check it out: I’m going to immerse you in Emily’s heart and mind for three hours and allow you to understand the kind of person you might not have thought about much.”

In a way, the whole book is an EXPOSITION BOMB. Mr. O’Nan must tell you about Emily’s family and her past and her town and her friends and her politics and her outlook on money and…gosh, so much. In my hands, Emily, Alone would probably not be a very good book. Why? Well, mainly because I don’t know as much about people as Mr. O’Nan does. But the gentleman chooses the right narrator. The third person limited narrator is planted firmly in Emily’s mind and is usually (if not always) in her corner.

What Should We Steal?

- Ignore the obligation to pack your story with too much action or external conflict. Try writing a story in which the conflict is far more internal. See what it feels like to write a story placing characterization over plot.

- Employ a third person limited narrator to facilitate characterization and exposition. When your story is all about an older character who is a little lonely, you might have trouble getting exposition across with a confidante. That third person limited narrator can tell the reader anything it likes.

- Respond to life’s little hiccups by breaking out a book instead of a sweat. If nothing else, I had three hours of reading time forced upon me. There are far worse things to complain about. Emily, Alone will always be the book I read while waiting for help to come, and I’m thankful that Mr. O’Nan was responsible for making an unpleasant experience more palatable.

Novel

2011, Emily Alone, Exposition, Stewart O'Nan

Title of Work and its Form: “M&M World,” short story

Author: Kate Walbert

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was originally published in the May 30, 2011 issue of The New Yorker. As of this writing, you can find the story on their web site. The story was selected for Best American Short Stories 2012 and can also be found in the anthology.

Bonuses: Here is the NPR archive of their stories about Ms. Walbert. This review of the story is not entirely favorable, but the writer seems earnest and the motivation for her criticism seems pure. A very interesting discussion takes place after this review at the excellent blog The Mookse and the Gripes.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Ginny made a promise to her daughters and now Maggie and Olivia are finally getting to go to M&M World in Times Square. Along the way, Ginny considers life’s ever-present dangers as Ms. Walters alternates between depicting the dramatic present and how Ginny related to “the girls’ father.” Before long, the inevitable happens: Maggie disappears into the M&M World crowd. After a moment of terror, Ginny gets the good news: Maggie had found her way to the stock room. As Ginny prepares her daughters to leave, she considers the experience in the context of an in-joke she and “the girls’ father” shared.

Well, Ms. Walbert uses white space to split the story into twelve sections. When you are reading the story for fun, you can simply work your way through them and enjoy the story. When you read analytically—which we should all do from time to time—it’s probably a good idea to jot down what happens in each section. That way, it’s easier for you to see how each piece contributes to the whole.

- Introduces Ginny, Maggie and Olivia and their situation. They’re going to M&M World. Danger is introduced in the form of Ginny’s concern over Olivia getting hit by a car. The girls trip each other. Danger. Introduction of “the girls’ father” and a vacation they took in Chile on which she saw a whale.

- Ginny considers her flaws.

- Arrival at M&M World. The ladies get ice cream.

- Flashback to vacation in Patagonia. The romantic moment when Ginny decided to have children.

- Ginny thinks about society. Maggie drops her ice cream.

- The women walk through M&M World.

- The scene in which “the girls’ father” discuss their breakup and how they will tell the girls about it.

- Maggie is lost.Fear.

- Back to the divorce discussion.

- Maggie is located.

- Rumination about the whale and what it meant to Ginny and “the girls’ mother.”

- The women leave the store; the dramatic present is united with the whale memory.

The third-person narrator allows Ms. Walbert to alternate somewhat between the dramatic present and flashback in order to build the significance of previous events. I don’t have any children, but I do believe that every parent is going to lose a child in the store at some point. Right? The little buggers are built to slip away and hide. On its own, that narrative may be a little thin. Ms. Walbert makes this common experience something far more special by including those flashbacks and making the story about Ginny losing her children, as opposed to some generic mother losing her children.

Ms. Walbert also uses her narrator in an unexpected way. I noticed early on that the narrator is very strongly aligned with Ginny. Look at the way the narrator characterizes the little girls: “They are gorgeous, bright-eyed, brilliant girls: one tall, one short, pant legs dragging, torn leggings, sneakers that glow in the dark or light up with each step, boom boom boom.” The statement seems to come from a person who cares about the girls more than an impartial narrator might. I’m particularly interested in the way that Ms. Walbert’s narrator refers to the ex-husband. He’s always called “the girls’ father.” The narrator withholds a name and seems to have something against the guy. The reader wonders why, all because of the way in which the narrator refers to him.

What Should We Steal?

- Contrast the dramatic present with significant moments from the past. Past is prologue; instead of TELLING the reader what an important moment means, you can SHOW them.

- Decide your narrator’s allegiances and exploit them. Your third person narrator could be standing beside your protagonist or could be sitting across a table from the protagonist with arms folded. The story will be influenced by the choice you make.

Short Story

2011, Best American 2012, Kate Walbert, Narrative Structure, The New Yorker

Title of Work and its Form: “The Sex Lives of African Girls,” short story

Author: Taiye Selasi (on Twitter @taiyeselasi)

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the Summer 2011 issue of Granta. It was subsequently selected for Best American Short Stories 2012 by Heidi Pitlor and Tom Perrotta.

Bonuses: Ms. Selasi is on quite a roll! Here is the Montreal Quarterly review of her first novel, Ghana Must Go. Here is what The Rumpus thought of the book. Here is an essay Ms. Selasi wrote about contextualizing her heritage. Here is what Karen Carlson thought of the story. (She really liked it!)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Pace

Discussion:

In this second person story, you are an eleven-year-old girl who is living with her extended family. Edem longs for her mother, but is surrounded by a colorful cast of relatives and servants. The story is split into nine sections, through the course of which we learn a great deal about the role that women of all ages play in Ghanian society. Edem is a fascinating age; young enough to be surprised when she walks in on her uncle…receiving…pleasure, but old enough to feel a stirring for Iago, a good-looking houseboy who changed his name out of love for Shakespeare. (I wonder why he chose Iago.) The story begins and ends as the citizens of Accra celebrate. By contrast, “you” are the subject of attempted abuse, unpleasantness that is thankfully interrupted by Auntie. The experience inspires a sad epiphany that will likely color the rest of “your” life.

It’s no surprise that Ms. Selasi’s debut novel has garnered extreme praise from reviewers; her writing is crying out for a vast canvas and her characters are deep and complicated. “The Sex Lives of African Girls” is most certainly a short story, and a very good one, but its structure is fairly different from those of the other stories in this edition of Best American. Through the course of nine numbered sections, Ms. Selasi tells Edem’s story and introduces her extended family and gets into a big discussion about gender roles in places like Ghana.

Ms. Selasi is using the second person to reduce emotional distance between Edem and the reader, which could have made it harder for her to address the culture at large. After all, a third person narrator would have had the freedom to say anything it wanted, regardless of time or location or character focus. Ms. Selasi began and ended the story at a big party, which eliminated some concerns. The reader grows to understand eleven-year-old Edem’s surroundings because they are all laid out in front of Edem, too. The non-Ghanian reader gets a taste of the culture as they meet people like Comfort and (of course) Uncle. I was reminded in some way of the wedding scene at the beginning of The Godfather. Are Italian, American or Ghanian parties really substantially different? Nah; people are the same all over. Ms. Selasi’s structure allows us to experience the little differences between cultures.

The story teaches the reader how to understand it. Ghanian culture may be a little bit obscure for some readers, so Ms. Selasi begins with a basic primer. Thinking about eleven-year-olds as anything but little baby children is certainly not normal for most people, so Ms. Selasi gives Edem a dress that is too long, resulting in a wardrobe malfunction. The hierarchy in Edem’s family (and in their servants) is unfamiliar, so Ms. Selasi employs flashbacks to teach us. Once we get the lay of the land in Edem’s life, we can properly empathize. (And boy, do we empathize!)

The narrative begins somewhat slowly as Ms. Selasi builds her world. Once that has been accomplished, she speeds up the events a little. There’s an honest-to-goodness action sequence in section VII that is a lot of fun to read. Edem runs through the homestead, making brief mention of everything that is happening along the way. “Sex Lives” isn’t a story about characters in isolation, but ones who populate a much larger world. The sequence allows you to see servants preparing for a party, “your” crush kissing your cousin and a muscular naked man before “you” change into new clothes. (The sequence even relates to the theme!) The first half of the story is a little bit slower before it speeds to a conclusion. Ms. Selasi creates suspense and tension by varying the pace.

What Should We Steal?

- Teach your reader how to understand your work. The reader is willing to believe anything you tell them, so long as they are properly prepared.

- Speed up the pace of your narrative once the background has been established. Think of exposition like a set of training wheels; once the reader can stay upright in the world you’ve constructed, go ahead and vary the pace of your story.

Short Story

2011, Best American 2012, Granta, Narrative Pace, Second Person, Taiye Selasi