Title of Work and its Form: “The Scruff of the Neck,” short story

Author: David Leavitt

Date of Work: 2001

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story originally appeared in 2001’s Volume 86 of The Southwest Review, one of those all-time-great journals that will never take any of my work. (I’ve come to grips with that.) If you have access to a library, ask your librarian to hook you up with the story through one of their databases. That’s what librarians do. That’s what they love. The story was reprinted in Mr. Leavitt’s collection The Marble Quilt. Then it was reprinted in Mr. Leavitt’s Collected Stories. (And what a bargain!)

Bonuses: Here’s an interesting Guardian review of Collected Stories. (Reviewer Edmund White hypothesizes that “The Scruff of the Neck” may have been influenced by Edith Wharton’s novella, “The Old Maid.”) Mr. Leavitt composed a poem for Quickmuse; he was given a topic and was limited to 15 minutes of composition time. Even better, his keystrokes were recorded so you can watch what he did in realtime. Pretty cool. Want to see Nath Jones read from Mr. Leavitt’s work? Sure, you do.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Opening Sentences

Discussion:

Rose is an elderly woman who is lucky enough to have a living aunt, Minna, who often asks her for a little help from time to time. The story begins as Rose enjoys a visit from her sister’s niece, Audrey, a young woman who is interested in building an epidemiology of the family tree. Before her visit, Audrey asks Rose to dig up birth certificates and any other official documents she can find that will help her writer her thesis. Rose, of course, obliges her descendant. Audrey arrives and asks about the family, eventually dropping an implied bombshell. I don’t want to ruin everything already-Go read the story! I chose one of Mr. Leavitt’s database-accessible stories for a reason!-but you can rest assured that Rose’s trip to the supermarket to help nonagenarian Minna find her car takes on an added dimension by the end of the story.

Mr. Leavitt introduces the theme of FAMILY in the very first sentence of the story:

Lily’s girl, Audrey, called Rose and asked if she could interview her; she was getting her master’s degree in epidemiology, she said, and for her thesis she wanted to prepare a medical history of the entire family.

The story is about genealogy and its implications; the protagonist’s family tree is made an issue from the very beginning. We get three generations in one sentence, don’t we? Rose is the eldest (clearly not the mother), Rose is the second generation and Audrey is the youngest. What an efficient way to begin the story!

Now, the great Lee K. Abbott offers his students very good advice: the writer does all of the work so the reader can have all of the enjoyment. Does Mr. Leavitt violate this dictate? After all, it seems as though he’s forcing you to do a little work by figuring out this family tree. I would argue that Mr. Leavitt is very much in the clear. He NEEDS to slip the genealogy into the exposition and it should probably come early. Mr. Leavitt performs a graceful pirouette by twirling Rose’s relations into the first sentence of the story. The second sentence is spoken by Audrey during the critical phone call:

“From soup to nuts” was how she put it. “And since you and Minna are the only ones of the brothers and sisters who are still alive, obviously it’s worth the trip to Florida to talk to you.”

This story is all about Rose decoding her origins and Mr. Leavitt contrives his narrative such that the reader spends the first two sentences aligned with Rose in this pursuit. The opening of the story immerses us in the narrative and subtly coaxes us into solving the central mystery. Best of all, we don’t even know that we’re being led along.

And while I’m talking about exposition…

It’s often hard for us to release basic information about our characters, isn’t it? Well, Mr. Leavitt lucks into a very easy method by which to tell the reader a protagonist’s family tree. A few pages in, you’ll notice that young Audrey asks for confirmation regarding the names and ages of Rose’s children. Audrey simply reads off the names and birthdates while Rose interjects a bit of characterizations about each.

Ordinarily, reading this kind of exposition might seem a bit tedious, but Mr. Leavitt folds it nicely into the flow of the narrative. (I also love that Mr. Leavitt devotes so much attention to hammering the ages of the characters home. It might otherwise be difficult to really feel that Rose is “old,” but Minna is much older still.)

This section of the story is also notable because Mr. Leavitt largely abandons dialogue tags and description. Why is this okay? Because he was so careful to establish the characters and their situation, the dialogue is all we really need to enjoy the story as it progresses. Speeding up the narrative at this point in the story is also critical because this section contains the story’s “big reveal.” The reader can devote more of his or her attention to this reveal because there is literally less prose between dramatic beats.

What Should We Steal?

- Ensure that the reader will only do as much calculation as they must. Yes, one who reads “The Scruff of the Neck” must figure out Rose’s genealogy. A reader of Harry Potter must learn a bunch about Hogwarts. The exposition must be fun, natural and graceful.

- Find interesting and graceful ways to insert what might otherwise be boring details. If birthdates, for example, are critical to your story, don’t just dump them into the story in a manner that is disconnected from the narrative.

- Trim other elements from your story to allow the important facets to shine in critical moments. Once the stage is properly set, all we really want is the dialogue that advances the story.

Short Story

2001, David Leavitt, Opening Sentences, The Southwest Review

Friends, David Chase’s HBO program The Sopranos is widely hailed as one of the shows that ushered in the latest “golden age” of television. James Gandolfini portrayed Tony Soprano, a New Jersey man who spent his time caring for his family and his waste management business. Oh yeah…he was also a big-time player in the Jersey mob.

The Sopranos ran from 1999 to 2007 and has influenced countless dramas that followed. (Breaking Bad, in particular.) The final episode was highly anticipated and Mr. Chase did his duty, giving the story an ending that viewers wouldn’t soon forget:

Many were confused by the abrupt cut to black. Others figured there was a problem with their cable connection. The reaction bummed me out a little; I loved that Mr. Chase ended the show on his own terms and that he made an artistic choice.

Didn’t Mr. Chase experience every writer’s dream? Millions of people were hanging on his every word and have since spent the better part of a decade deciding what the piece means to them. “Masterofsopranos” offered my favorite analysis. Jamie Andrew produced a thoughtful explanation for Den of Geek!

Well, Mr. Chase offered some after-the-fact clarification with regard to Tony’s true fate. I’ve linked an article, but you know what? It doesn’t matter what Mr. Chase thinks. He was kind enough to give us the work and it now belongs to each viewer.

Now, I know that Twitter isn’t really good for much. It is, however, a means of communication and must have some intrinsic value. For instance, the great Joyce Carol Oates offered some ideas regarding the Sopranos finale that we should bear in mind:

Ms. Oates retweeted this nugget of timeless wisdom:

Writing is a double-edged sword. Writers get the pleasure of sharing creations with readers…then the writer must accept that each reader invariably makes that creation their own. We thank Mr. Chase for giving us Tony and Paulie and Christopher and Carmela and Adriana (RIP), but his act of giving also means that they now belong to us.

Did Tony get shot? Your theory is worth just as much as the impulse that guided Mr. Chase during his long hours at the keyboard.

Television Program

2007, GWS Twisdom, Joyce Carol Oates, The Sopranos

Title of Work and its Form: “Bible,” short story

Author: Tobias Wolff

Date of Work: 2007

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story originally appeared in The Atlantic‘s 2007 fiction issue. As of this writing, you can find “Bible” on the magazine’s web site. (Feel free to say thank you to those fine folks!) The piece was subsequently chosen for Best American Short Stories 2008 by Salman Rushdie. Ann Graham was nice enough to compare a revised version of “Bible” to the original. Thanks, Ms. Graham!

Bonuses: Here is a great Paris Review interview with Mr. Wolff.

Want to see Mr. Wolff discuss his excellent book, Old School?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Power Imbalances

Discussion:

What a great story. Maureen is a schoolteacher who has spent the evening with friends at the Hundred Club. In the first two pages, we learn that Maureen’s life is not as perfect as she wishes it were; she has serious problems with her grown grown daughter, Grace. One is led to believe that these are the kinds of obstacles that could be overcome with a little mutual humility and maybe a bottle of wine, but that has not yet happened. After we feel like we know Maureen, she is carjacked by a mysterious man with an accent. He forces his way into her car and tells her to drive.

I don’t want to ruin everything in the synopsis. Just read the story. It isn’t very long and it’s available on the Atlantic web site.

Done? Okay.

I had a lot of fun re-reading this story in the Best American volume in part because it occurred to me that I remembered the story from its original public…in 2007. What in the world makes a story so great that a reader will remember it seven years later?

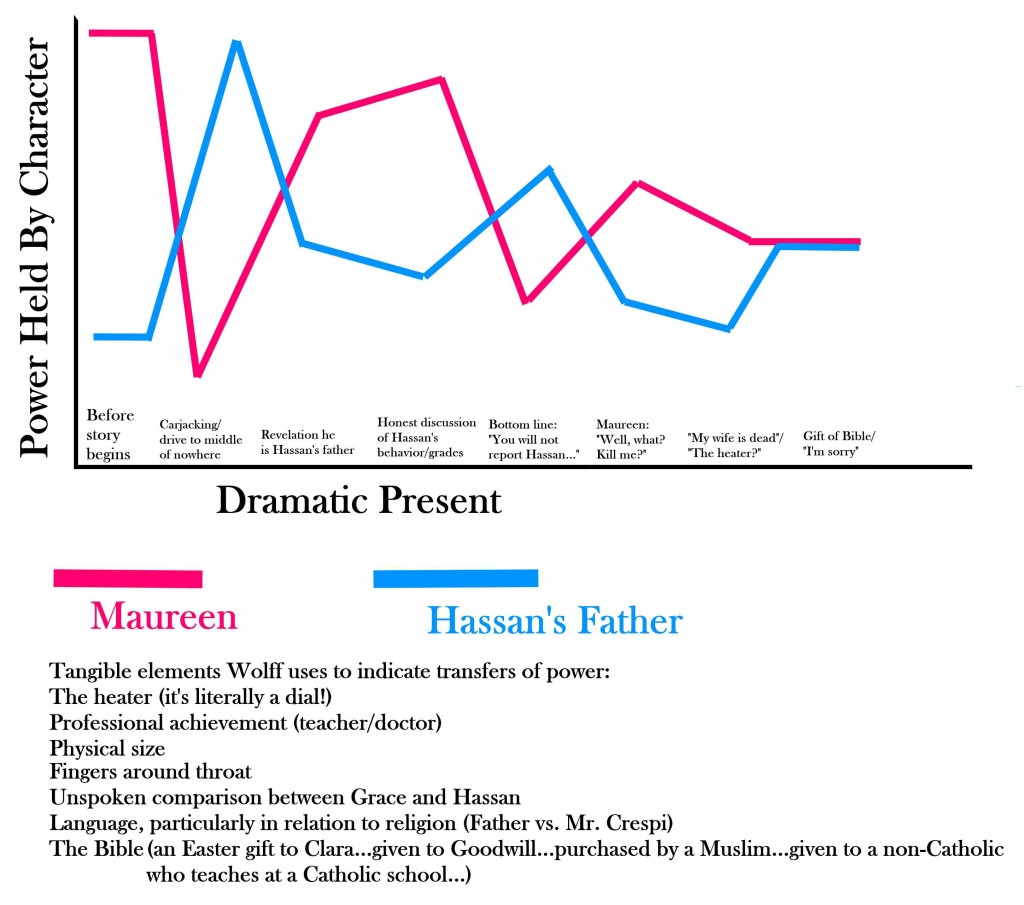

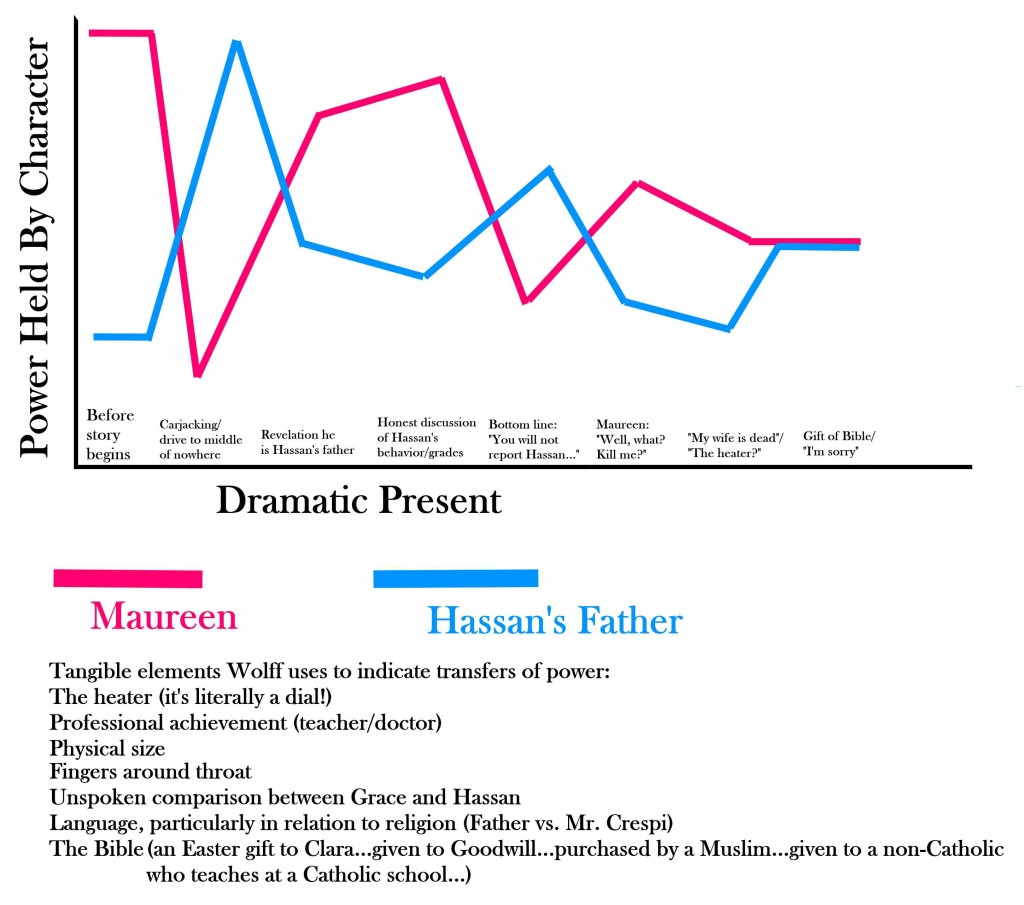

One big reason that the story maintained its power in my mind was the way that power shifted between Maureen and the man (Hassan’s father). Before the two meet, Maureen has high status; she’s a financially secure teacher who is taking advantage of her education. Hassan was a doctor in his home country…and now he is not.

The story is exciting because it’s a real fight between two characters that is based upon big, important issues. Why do we love Law & Order? Because we vacillate between “He or she is guilty of assault!” and “He or she is innocent of that assault!” Why is 12 Angry Men so great? It’s a big fight between twelve characters that determines a man’s innocence and future. Wolff has our attention for the same reasons: we want to know what happens and we want to know what the characters (and Mr. Wolff) are ultimately saying about the big issues in the story. (What parents will do for their children…the sadness that can result from the immigrant experience in America…when mercy should be granted…)

Okay, okay. Fine. I’ll make a chart that demonstrates that “Bible” is so great, in part, because it’s a live wire that keeps us interested:

The play Doubt is great because we are forced to empathize with both characters and we’re not spoonfed the truth. We love long tennis rallies because they’re a fight between two great players.

The play Doubt is great because we are forced to empathize with both characters and we’re not spoonfed the truth. We love long tennis rallies because they’re a fight between two great players.

“Bible” derives its power from the way it takes away our certitude with respect to the characters and the story’s outcome.

Mr. Wolff makes a choice halfway through the story that he can only make because he did such a fantastic job establishing the characters and their situation. If you’ll notice, there are few dialogue tags in the scene during which Maureen and Hassan argue about the place of women in Islam, whether Hassan will be reported to Father/Mr. Crespi and whether Hassan is a decent enough student to be a doctor. The reader really doesn’t need dialogue tags because there are only two characters. We don’t need “stuff”/description of tone or action during dialogue because Mr. Wolff already brought the characters to such vivid life.

Omitting the dialogue tags is a fun choice because it allows us to read the story faster and to concentrate on the battle being waged between the two characters. In order to make use of this technique, unfortunately, you must have well-established characters who actually say interesting and powerful things. (See? You knew there would be a catch!)

What Should We Steal?

- Make use of power transfers. I’m a big Detroit Tiger fan. Would I love if they won every game they played? Sure. But there wouldn’t be too much drama in that season, would there?

- Omit dialogue tags and description during the meat of an argument. The reader should understand the differences of opinion between characters during your climax…why not consider releasing that dialogue uninterrupted?

Short Story

2007, Best American 2008, Power Imbalances, The Atlantic, Tobias Wolff

Title of Work and its Form: Fish Bites Cop! Stories to Bash Authorities, short story collection

Author: David James Keaton (on Twitter @spiderfrogged)

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: I was amused by the playful manner in which Mr. Keaton tells his fans how they can get the book, so I share it here:

If you’re looking to buy it (did I already post these retailers somewhere? oh, well), here’s a link to the Comet Press website, as well as links to Barnes & Noble (for locals), Carmichael’s Bookstore (for locals), Powell’s, Indiebound, and Amazon. I listed those in order of preference. Buy it from the publisher or the real stores first, unless you need it on Kindle. Who knows where that Amazon money goes.

Hey, Fish Bites Cop! has a book trailer!

Bonuses: Here is “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel,” one of my favorite stories from the book.

Want to see Mr. Keaton read his work? Sure, you do:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing:

Discussion:

Mr. Keaton is very clear with regard to the theme of his collection. Each of these stories does indeed involve “authorities.” There are police officers, the captain of a fishing vessel, high school coaches, paramedics…Mr. Keaton may be very focused, but he doesn’t have a one-track mind. Indeed, Fish Bites Cop! is bursting with creativity; the gentleman doesn’t go more than a page or so without turning an underlinable phrase or making some kind of connection that may elude most readers. (Why else do we read, after all?)

Here is the book’s table of contents. (I added the POV and page counts myself, of course.)

| Title |

POV |

Number of Pages |

| Trophies |

3rd |

2 |

| Bad Hand Acting |

3rd |

8 |

| Killing Coaches |

1st |

8 |

| Schrödinger’s Rat |

1st (we) |

13 |

| Life Expectancy In A Trunk (Depends on Traffic) |

1st |

8 |

| Greenhorns |

3rd |

12 |

| Shock Collar |

3rd |

4 |

| Third Bridesmaid From The Right (or Don’t Feed The Shadow Animals) |

1st |

11 |

| Burning Down DJs |

1st |

6 |

| Shades |

3rd |

6 |

| Three Ways Without Water (or The Day Roadkill, Drunk Driving, And The Electric Chair Were Invented) |

3rd |

11 |

| Heck |

3rd |

4 |

| Do The Münster Mash |

3rd |

4 |

| Either Way It Ends With A Shovel |

3rd |

14 |

| Castrating Firemen |

1st (directed at silent interlocutor) |

5 |

| Friction Ridge (or Beguiling The Bard In Three Acts) |

Play |

14 |

| Doppelgänger Radar |

3rd |

4 |

| Queen Excluder |

3rd |

12 |

| Don’t Waste It Whistling (or Could Shoulda Woulda) |

1st (directed at silent interlocutor) |

3 |

| Three Minutes |

3rd |

3 |

| Bait Car Bruise |

1st |

3 |

| Clam Digger |

1st |

8 |

| Swatter |

1st |

8 |

| Three Abortions And A Miscarriage (A Fun “What If?”) |

3rd |

14 |

| Catching Bubble |

3rd |

3 |

| Doing Everything But Actually Doing It |

3rd |

9 |

| The Living Shit (or Mosquito Bites) |

1st |

6 |

| Warning Signs |

3rd |

3 |

| The Ball Pit (or Children Under 5 Eat Free!) |

3rd |

6 |

| Nine Cops Killed For A Goldfish Cracker |

3rd |

Mr. Keaton bowls us over with at least one lesson: like him, we should write a lot. Now, I’m sure he has some sort of science fiction-type device that gives him 30 hours a day instead of our 24, but we really have no excuse. I know…I know…you would finish a story, but…

- You have a Great Writers Steal essay to write.

- You’re not in a good mood.

- You don’t have any of your fountain pens with you.

- You’re stressed out about teaching-type stuff.

- You figure no one wants to read anything you write anyway.

- You realize you’re not good enough to do much of anything.

- You’re bummed that your Tigers aren’t playing as well as they should and that Braxton Miller is out for the 2014 season.

- Ooh…there’s an Onion video I haven’t seen before.

There’s only one solution to these very common problems: Just write stuff. Duh. We all know we should just shut up and finish a piece, but that can be hard to do sometimes. But do it anyway. Just look at all of the stuff that Mr. Keaton has published in only a few years. So let’s get back to work, right?

Mr. Keaton also seems to enjoy a technique that reminds me of the work of Lee K. Abbott in some ways. Check out some first sentences from Fish Bites Cop!:

“She was sure one of them was watching her.”

“Before the night ends with me crashing through the woods in a stolen police car, I’ll drive around stuck on one thought.”

“There were sitting down to dinner when the phone rang.”

“I will leave work to get you a cigarette because you’re crying.”

(in italics) “Are you going to bury someone? Or dig someone up?”

What do we notice? The story is well and truly kicked off. Not only do we have plot and character and point of view, but we also have some stakes built into the story. Now, it can be hard to have MASSIVE stakes present in the first sentence, but Mr. Keaton lets you know that SOMETHING COOL WILL HAPPEN and THE EVENTS MEAN SOMETHING TO THE CHARACTERS, SO THEY SHOULD MEAN SOMETHING TO YOU.

Compare to…hmm…what books do I have in front of me:

Aubrey Hirsch’s “Theodore Roosevelt:” “Teddy Roosevelt is almost certain that his daughter, Lee, is a lesbian.” (CHARACTER, POV, PLOT, STAKES)

Elmore Leonard’s “How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman:” “Carlos Webster was fifteen years old the time he witnessed the robbery and murder at Deering’s drugstore. (CHARACTER, POV, PLOT, STAKES)

Lee K. Abbott’s “Dreams of Distant Lives:” “The other victim the summer my wife left me was my dreamlife, which, like a mirage, dried up completely the closer we came to the absolute end of us.” (CHARACTER, POV, PLOT, STAKES)

I think these examples are even more potent than the ones I discussed in one of my GWS Videos:

The point is that good things often happen when you supercharge your first sentence and make sure that it contains:

- A hint about the central character that intrigues us or establishes important aspects of his or her personality.

- The establishment of the POV so we’re not subconsciously wondering and we can relax into the narrative.

- Something that immerses us in the eventual plot of the story.

- An indication of the tangible or emotional stakes for the protagonist, or at least an indication that there WILL be BIG STAKES.

Mr. Keaton is particularly good at creating really cool images. For example:

Only a guilty man soaks up enough electricity to power a city block, pulling fishhook after fishhook of Taser wire from his torso, all while cuffing any cop that got too close with fists half the size of Thanksgiving turkeys.

[He’s describing clams.] At first, they’d just be foam trails off the tips of something almost invisible. But when I’d lean down on my elbows, I’d see they were actually creatures that moved like anything else moved when it was exposed. They tried to hide. Looking close, I could see them desperately digging to bury themselves before the next wave. Their time, jelly-like tongues would roll out like party favors, start twitching and shoveling, and then, impossibly, balance the entire structure on one end, then pull themselves down, down and gone.

So how do we pump up our writing with cool images?

I’m not sure if I’ve ever done this before, but let’s put a writer who is worse than Mr. Keaton to THE GWS TEST. Today, we’ll look at the work of a crummy writer and see if his stuff can be improved with this advice.

Our contestant today is…me. Let’s see. One of the stories I’m shopping around is called “Masher Doyle.” Let’s check out the first sentence:

Masher Doyle came into my life at the time I most needed him.

There is a hint about the protagonist…good, good…the first person POV is established…the plot certainly revolves around the relationship between the narrator and Masher Doyle…and there are emotional stakes; the narrator is describing a time that was bad for him. Okay. Not quite Mr. Keaton-worthy, but good enough. Let’s look at one of the crummy images in my story and see if we can’t make it better.

Okay, here’s one:

When my mother sent me to the corner store for milk, she slipped me an extra forty cents so I could buy a pack of baseball cards. Before heading home, I would sit on the curb and slip my dirty thumbnail under the flap, pull it, then flip through my new cards.

What would Mr. Keaton do? He would use powerful verbs and powerful adjectives. Do I? “slipped, extra, buy, sit, slip, dirty, pull, new…” I dunno. Those aren’t the most energetic words around.

Here’s another bit from Mr. Keaton:

It reminded him of a Halloween pumpkin he forgot to carve once as a kid, when he just drew eyes, nose, and a mouth with a black Magic Marker and then forgot about it until New Year’s. When he picked it up, his thumb sunk into its eye as easy as he imagined a real eye would accept its fate, and it collapsed around his grip in a gush of rotten orange and black.

Yeah, see? We all need to use verbs and adjectives that crackle with energy.

What Should We Steal?

- Be prolific. If you’re a writer, you should be writing, right? So get back to it after you click on a few more GWS essays and watch a couple more of my videos.

- Add some nitrous to your first sentence. I haven’t seen any of the Fast and Furious films, but I’m under the impression that nitrous adds big power to a car, just as you should put big power into your sentence.

- Employ energetic verbs and adjectives to create powerful descriptions. Words can excite people as much as ideas.

Short Story Collection

2013, Comet Press, David James Keaton, FISH BITES COP!

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

David James Keaton is a very interesting fellow. The gentleman is very prolific and seems very cool. He loves music and crime fiction…but I’m not sure he’s such a big fan of authority figures. His aversion to them is fine by me, as it resulted in the stories presented in Fish Bites Cop! Stories to Bash Authories, a book you should certainly get into your hands and heart. Here is the entertaining manner in which Mr. Keaton explains how you can order the collection:

If you’re looking to buy it (did I already post these retailers somewhere? oh, well), here’s a link to the Comet Press website, as well as links to Barnes & Noble (for locals), Carmichael’s Bookstore (for locals), Powell’s, Indiebound, and Amazon. I listed those in order of preference. Buy it from the publisher or the real stores first, unless you need it on Kindle. Who knows where that Amazon money goes.

Ordering Mr. Keaton’s first novel is a little easier; Broken River Books has made signed hardcover copies of The Last Projector available through their web site. The book will be worth a look; one of the things I wondered while reading Fish Bites Cop! was what Mr. Keaton would do when he had a vast canvas at his disposal instead of many small ones.

Sure, you might want to know about how Mr. Keaton articulates his overall philosophy regarding fiction. You may want to read a 10,000-word essay in which he writes in great detail what makes a story interesting to him. Well, look elsewhere for those things. I’m really curious about some of the small choices that shaped the stories of Fish Bites Cop!

1) Okay, so I made a chart of Fish Bites Cop!’s table of contents as a public service. (You can never find a simple table of contents for story collections!) I also did it so I could look at stuff a little analytically.

| Title |

POV |

Number of Pages |

| Trophies |

3rd |

2 |

| Bad Hand Acting |

3rd |

8 |

| Killing Coaches |

1st |

8 |

| Schrödinger’s Rat |

1st (we) |

13 |

| Life Expectancy In A Trunk (Depends on Traffic) |

1st |

8 |

| Greenhorns |

3rd |

12 |

| Shock Collar |

3rd |

4 |

| Third Bridesmaid From The Right (or Don’t Feed The Shadow Animals) |

1st |

11 |

| Burning Down DJs |

1st |

6 |

| Shades |

3rd |

6 |

| Three Ways Without Water (or The Day Roadkill, Drunk Driving, And The Electric Chair Were Invented) |

3rd |

11 |

| Heck |

3rd |

4 |

| Do The Münster Mash |

3rd |

4 |

| Either Way It Ends With A Shovel |

3rd |

14 |

| Castrating Firemen |

1st (directed at silent interlocutor) |

5 |

| Friction Ridge (or Beguiling The Bard In Three Acts) |

Play |

14 |

| Doppelgänger Radar |

3rd |

4 |

| Queen Excluder |

3rd |

12 |

| Don’t Waste It Whistling (or Could Shoulda Woulda) |

1st (directed at silent interlocutor) |

3 |

| Three Minutes |

3rd |

3 |

| Bait Car Bruise |

1st |

3 |

| Clam Digger |

1st |

8 |

| Swatter |

1st |

8 |

| Three Abortions And A Miscarriage (A Fun “What If?”) |

3rd |

14 |

| Catching Bubble |

3rd |

3 |

| Doing Everything But Actually Doing It |

3rd |

9 |

| The Living Shit (or Mosquito Bites) |

1st |

6 |

| Warning Signs |

3rd |

3 |

| The Ball Pit (or Children Under 5 Eat Free!) |

3rd |

6 |

| Nine Cops Killed For A Goldfish Cracker |

3rd |

22 |

There are 30 stories in the book.

The longest story is 22 pages.

9 of 30 are longer than ten pages.

10 of 30 are between six and ten pages.

11 are under five pages.

How come the stories are so short? Are you influenced by the Internet-inspired growth of the popularity of short-shorts? The stories are very “idea-oriented”…are you consciously trying to get the idea out of there as quickly as possible? Your prose is fun and punchy; do you feel you need to accentuate that part of your writer’s toolbox?

DJK: Interesting! These statistics are new to me. Did you like the scary fish picture on the contents page? I like that fish. That’s what I imagine goldfish crackers look like in our bellies. Well, as far as length, a couple venues that I was submitting to did dictate length. For example, “Warning Signs” went to Shotgun Honey, which had a 700-word limit, an odd but challenging (and kinda arbitrary) number. Also, many of these shorter pieces were written when I had zero publications to my name and I thought I could somehow crack that elusive code by writing tiny flash pieces and “get my name out there.” Translation: Give fiction away for free! Instead, this mostly meant getting Word Riot rejections five or six times a day (fastest rejections ever!). And this might be kind of a boring answer, but most of the stories are as long as they wanted to be. Well, a more boring answer would actually be “as long as they need to be.” But, truthfully, some of them probably needed to be shorter. But it’s not about what they need. It’s what we need, right?

2) A lot of us have real trouble figuring out character names. Many of your protagonists are named “Jack” or “Rick.” Why do you do that for? Are you making a point about how everyone is kinda the same, regardless of names? Or do you just like that the names are short and easy to type?

DJK: You mentioned to me in an earlier conversation how Woody Allen claimed he used names like “Jack” because they are so much more efficient, and I’m totally on board with this reasoning. It’s like Jeff Goldblum in The Fly and his closet is full of the same shirts and pants and jackets – because this means he doesn’t have to expend any brainpower on unimportant things. Although, to be fair, Goldblum’s character does all his best thinking once his girlfriend buys him his first very ‘80s bomber jacket. But for me, naming a character “Jack” is also like a shortcut to not having to name someone at all. “Jack” feels like a not-name to me, not as obviously anonymous as “John,” and it sort of sounds like a verb, too, so that’s a bonus. I’m just not that interested in names. I also don’t enjoy describing characters. Not sure where the aversion comes from, but I’d number little stick figures if I could!

Also, whenever there’s a “Jack” who is a paramedic, that’s actually a tiny snippet of my upcoming novel The Last Projector. In that book, there’s just the one Jack. Well, he’s kind of a couple people, too, but that’s another story. But in Fish Bites Cop!, the Jacks are different people, unless they’re paramedics. If that makes any sense. This answer has gotten so long and thought-consuming that I’ve now reconsidered and may start using normal names again.

3) “Nine Cops Killed For A Goldfish Cracker” is a really cool story. And you do a cool thing in it. There are three big countdowns that control the progression of the story.

- Jack starts killing law enforcement officers…the title lets us know he’s going to reach nine by the end of the story.

- One of the goldfish in Jack’s bowl ate a thousand dollar bill. The fish are executed one by one in search of the prize.

- The narrator compares Jack’s journey to that of a football player making his way down the field to the end zone.

How did you make use of these countdowns in your story? How did you make sure that the “mileposts” passed quickly, but not too quickly? How did you make the countdowns seem organic instead of all contrived and stuff?

DJK: Thanks! The countdown that shaped the story the most was the deaths of the titular “nine” cops (ten, actually). By thinking of creative ways to murder them, it gave me a very convenient way to map it all out. The countdown of the dying fish was a heavy-handed parallel to the dying cops, so that countdown was supposed to be like a Star Trek mirror-universe version of what the drying fish and dying cops were going through. The yard-line countdown was added in the 11th-hour of writing, to smooth it out and to accelerate things a bit more. Once I added yard lines, the rest of the football imagery started popping up organically and things really got fun. But the deaths of the police officers were definitely the story’s engine, and not just because I knew that a reader would expect exactly nine police officer deaths as promised, and I knew I had to deliver. But it drove the story because, when I wrote it, I’d been working late hours at my former closed-captioning job, and we had short, unhealthy lunches built into our demanding captioning duties, so that countdown was also a way to get a little bit of the story done each night on my 15-minute lunch break. One little murder a day, I’d tell myself, and I’d be home free in a week! How many times have we said that to ourselves?

4) Several of the stories have alternate titles. (For example, “The Living Shit (or Mosquito Bites)”). Coming up with titles is hard for a lot of us. Why did you include some alternate titles?

Some of the titles are really descriptive and reflect what happens in the story (“Killing Coaches”) and some are a little more “fun.” What do you think is the relationship between the title and the story?

DJK: Most of the alternate titles in the collection are their original titles. “The Living Shit,” for example, was renamed “Mosquito Bites” to make it more palatable and get it published. But I always preferred the uglier title, so I switched it back. In fact, the original title of “Nine Cops Killed for a Goldfish Cracker” was “Fish Bites Cop.” But instead of adding an alternate to that already very long title, I just called the collection Fish Bites Cop instead. Problem solved! That meant the newspaper headline at the end of the story is also swapped around. Now the newspaper reads, “Fish Bites Cop!” too. Which I kind of prefer, actually. And hijacking that story title to make it the title of the book suited the collection in many unexpected ways.

But, yeah, some of the “fun” titles were titles I had kicking around that I really wanted to write a story around. Like “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel” was actually an email subject line that my friend Amanda and I passed back and forth at that captioning job whenever we were disgruntled. So that title was her idea actually. To write a story around it, I just had to think of the two “ways” that would go with it. And the question of burying someone or digging them up seemed to be the only option.

5) “Greenhorns” and “Clam Digger” are two of my favorite stories in the book. They’re also a little different from the other stories, as they feature fantasy/supernatural elements.

How come there are only a few horror-y stories in the book? The rest seem extremely hard-boiled and realistic. (Even though the stories feature “extreme” events, of course.)

DJK: When I wrote most of these stories, I was in grad school at the University of Pittsburgh, and many were sort of an affectionate raspberry to the typical MFA-style “lit” story. So I was purposefully playing with every genre I could. The fact that the vast majority also incorporated authority bashing of some kind is a mystery for a psychologist to unravel. Hopefully, a psychologist who is just starting out so that he or she is real hungry and really, really wants to get to the bottom of these things. Or maybe a recently martyred movie psychologist who will absolve me with four magic words, “It’s not your fault.”

6) You’re real good at using unexpected verbs.

In “Bad Hand Acting,” the janitor doesn’t “walk around” the mob of police. He “orbits” them.

In “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel,” the character doesn’t just “look at” or “see” a bunch of bodies in his car trunk. He “studies” the bodies and “counts” the “elbows and knees as tangled as his guts.”

In “Shades,” the narrator “drops” a dollar in a peddler’s hand, which is a lot less secure than “handing” a bill to a person.

How do you know when to use a regular old boring verb and when to use a cool, unexpected one?

DJK: Back in school, I was told verbs are very important to bringing a scene to life and their power shouldn’t be squandered through use of lazy words like, “are” and “to be,” like I just did in this sentence.

7) One of the things I really like about the stories is that you include a lot of fun “extra” stuff in your work. “Clam Diggers” is very much a story about a man relating how his brother disappeared. Still, you manage to sprinkle in a cool image/story about how the father taught the sons to turn bathroom graffiti swastikas into “neutered” sets of boxes. Unfortunately, writers like me have led sheltered, boring lives, depriving us of the opportunity to come across these kinds of interesting anecdotes and ideas. How many of these cool things in the stories come from your real life? Should sheltered writers like me just allow myself to make up stuff? I’ve obviously never planned an inside job scam on a casino…should I just stop restricting myself and assuming I couldn’t write such a story?

DJK: Neutering swastikas into tiny four-paned windows is a favorite pastime of mine, as I found that moving to Kentucky means more than the usual quota of bathroom-stall neo-Nazi graffiti. See this is where the revolution will begin… on the toilet! And many of the digressions, er, details do come from my day-to-day or past adventures. I did win and lose and win back about three grand at roulette, and I committed all those ridiculous infractions at the roulette wheel at the MGM Grand Casino in Las Vegas. I’d like to say that was research, but it was my friend’s crazy wedding. I didn’t try to scam them, of course. All the flavor that my personal experience can bring to the stories stops just short of the actual crimes. Except for one. Maybe. Sort of. Next question!

8) You REALLY like to start stories with the inciting incident or with a sentence that represents the overarching feeling of the piece or its narrative thrust. See?

Shades: “She was sure one of them was watching her.”

Burning Down DJs: “Before the night ends with me crashing through the woods in a stolen police car, I’ll drive around stuck on one thought.”

Queen Excluder: “There were sitting down to dinner when the phone rang.”

Castrating Firemen: “I will leave work to get you a cigarette because you’re crying.”

Either Way It Ends With A Shovel: (in italics) “Are you going to bury someone? Or dig someone up?”

How much of this is planning and how much comes in the second draft? Are you only doing it because most of these are crime-related stories and plot is really important?

DJK: Those examples were part of the original drafts. I’ve always been a fan of getting things going in the first sentence, to engage both the reader and the writer. And because I can’t wait to get the main idea out, front and center (like the “Are you going to bury someone or dig them up?” question in “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel”) and because I trust myself a little more with the plot rather than the prose. At least until the story gets cooking.

9) So I think I understand why you have thirty stories about authority figures (police officers, firemen, paramedics). It’s probably the same reason I have 150 stories about ugly dudes whose flawed natures has resulted in the fact that none of them have ever had a healthy relationship with a woman. These are topics of particular and personal interest to us, so we’re going to write about them.

What I wanna know is how you figured out the order for all of the stories. (We’re all hoping to have the same assignment someday!) How come the super-long award-winning story was last instead of first? How come the shortest story was first? What kind of experience were you trying to shape for the reader?

DJK: When it turned out I’d accumulated thirty stories that punished police officers, firemen, paramedics, high school coaches, etc., I was kind of surprised. It really wasn’t a conscious effort. Well, there were probably about twenty stories stockpiled with this similar theme before I realized the connection, and then I wrote ten more because I felt like I was on a roll and wanted to get it all out.

It’s still not all out though. A beta reader is going through my novel, The Last Projector, right now, and for kicks he counted up the total uses of the word “cop,” “officer,” and “police.” You might enjoy this with your statistics fetish earlier!

In 500 pages, there are around 700 uses of these terms. Second most used is the word “fuck” with 600. And most of those “fucks” and “cops” are probably pretty closely intertwined. And this is not a novel about police officers. So I guess it’s out of my hands.

As far as the order of the stories, that was sort of complicated:

“Nine Cops Killed…” wraps up the book because it’s the title story, and I feel like it’s a big party, a fun bash where the reader can be rewarded for making it through the whole thing. And the shortest story starts things because “Trophies” felt like a mission statement to me. It had a lot of the elements that are consistent throughout, regardless of the genre hopping.

But as far as the order of the stories, I spend a loooooooong time on that. I definitely “mix-taped” it High Fidelity style. The first “song” starts off fast, then the next song kicks it up a notch. Then the next song slows things down a notch, etc. etc. And I also wanted stories that were first-person to avoid following each other, lest people think those “Jacks” were the same Jack, of course. And I wanted the genres to be spread out, so that people didn’t expect a third monster movie after a monster double feature. And after all that work of mix-taping, I read an article on HTML Giant that declared very definitively that, “Short Story Collections Are Not A Mix Tape!” and then I was satisfied that I had done the right thing.

10) Look at the last few pages of “Clam Digger.” This cool story is told by a first-person narrator who is relating events that happened a long time ago. He therefore has access to a lot more information than the younger version of himself.

So the narrator lets us know this is THE STORY OF HOW HIS BROTHER DISAPPEARED AND YOU CAN BELIEVE HIM OR NOT; HE KNOWS WHAT HE SAW. (We’re also informed he’s participating in some kind of interview.)

So the bulk of the story finds the narrator telling the story in the past tense, chronologically jumping from one significant event to the next.

But check out the end of the story. We’re getting the “money shot,” so to speak. The mystery of the brother’s disappearance is being revealed…

Then you cut to a new section, leaping from the past to the present to the past again. Why did you break the pattern established by the rest of the sections? What was the effect you were trying to create? Are you willing to apologize for my newfound fear of clams and other mollusks?

DJK: I guess that was an attempt to build suspense, sort of use those Sam Peckinpah directorial editing tips where you cut away right when the shot has peaked. I also maybe stutter-stepped there at the end because I wasn’t sure how I was going to wrap it up. The natural ending of that story felt like it should be in the past, since that’s where the mystery was, but there had to be resolution in the present, too. So I tried to do both, at the risk of the dog in Aesop’s fable who growls at his reflection in the water and loses both bones.

“Clam Digger” was also my first run at a “Lovecraftian” story. So I had some tortured soul spinning some yarn about the horribleness he’d witnessed, some large ocean-dwelling critter that may have driven him insane. But other genres started to cross-fertilize while I was writing it, and the story that resulted is really more psychological horror than anything.

I do apologize for your new clam and mollusk aversion, though. But it’s better than an aversion to naming characters, so you should be thankful! And it’s only fair this happened to you because those things freak me out, too. I mean, look at clams for a second, if you have one handy. You think it’s sticking its tongue out at you, but it’s a foot? You think it’s sticking its eyes out at you, but that’s its nose? That’s insanity on the half shell right there.

David James Keaton’s award-winning fiction has appeared in over 50 publications. His first collection, Fish Bites Cop: Stories to Bash Authorities, was named This Is Horror’s Short Story Collection of the Year and was a finalist for Killer Nashville’s Silver Falchion Award. His debut novel, The Last Projector, is due out this Halloween through Broken River Books.

Short Story Collection

2014, Comet Press, David James Keaton, FISH BITES COP!, Why'd You Do That?

Title of Work and its Form: “Man and Wife,” short story

Author: Katie Chase

Date of Work: 2007

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story originally appeared in the Summer 2007 issue of The Missouri Review, one of the best journals for fiction. TMR has been kind enough to post the story on their web site for free. “Man and Wife” was subsequently chosen for Best American Short Stories 2008 by Salman Rushdie and Heidi Pitlor.

Bonuses: Here is “Every Good Marriage Begins in Tears,” a story Ms. Chase published in Narrative. Here is “Babydoll and the Ring of Chastity,” originally published by Five Chapters. And here is “The Sea That Leads to All Seas,” a story originally published in Prairie Schooner.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Tone

Discussion:

Hooray! Mary Ellen just got engaged to be married to Mr. Middleton, a wealthy man with a sweet moustache.

Oh no! Mary Ellen is nine-and-a-half years old.

Ms. Chase offers us a wonderfully disturbing story in which Mary Ellen is promised to Mr. Middleton. Her friend Stacie comes by to play Barbies on occasion and Mr. Middleton comes for respectable Sunday evening dinners. Mary Ellen’s mother tells the young lady some of what she’ll need to know to be a good wife. I don’t want to ruin everything. TMR has the story up for free…just go read it.

The story reminds me of Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” in a few ways. Don’t get me wrong; the stories are very different, but Ms. Chase is able to create a similarly delicious sense of foreboding in the piece. The story is so much “fun” that I made marginal notes that demonstrate how deeply I engaged with the story: “WTF world is this?” “Say WHAT?” “Awesomely disturbing.”

Perhaps the biggest reason Ms. Chase engages us so deeply is because she treats the world of “Man and Wife” as utterly normal. Now, every single person who reads “Man and Wife” is repulsed by the idea of preteen children being sold into marriage. Ms. Chase doesn’t allow Mary Ellen (narrating what happened eight years ago) or any of the other characters to violate the conventions of their society. Can it be tempting to remind a reader that it’s super gross for a grown man to play Barbies with his preteen fiancee? Sure. But it’s not necessary and it’s undesirable; such a scene is NOT super gross in Mary Ellen’s world.

Ms. Chase also follows Shirley Jackson’s lead by slowly layering in the “weird” stuff. In the first few pages, Mary Ellen tells us that we’re going to read the story of HOW EVERYTHING CHANGED FOR HER. Okay, normal. Then her parents say they have big news. Okay, normal. Then the parents toast the good news and there’s a little bit of ooh-child-getting-a-sip-of-alcohol stuff. Okay, normal. We know SOMETHING is up, but we’re not quite sure what it might be.

Then Ms. Chase hits us with the crazy: “He’s gone ahead and asked for your hand. And we’ve agreed to it.” This was the point at which I knew I was going on a “fun ride,” as I wrote in the margin. Ms. Chase successfully immersed me in a different world and I couldn’t wait to see what would happen next because the world functioned according to rules so different from ours.

I have some cinematic examples!

The film Happiness disturbed the crap out of me, so much so that I am a little scared of Dylan Baker, even though I know Mr. Baker was simply reading words from a script. I simply don’t live in a world in which it makes sense that a father would drug his child’s friend for…unpleasant…purposes. I was immersed in the film because it was like looking through a telescope into an alternate universe.

The great Alexander Payne (with co-writer Jim Taylor) shook me from real life and dragged me into the world of Ruth Stoops in their classic film Citizen Ruth:

Ruth (Laura Dern) begins the film huffing patio sealant behind a hardware store. Then she is arrested and discovers she’s pregnant…again. The judge offers her a choice: have an abortion and go free or have the child and stay behind bars. Ruth begins bopping between soldiers on both sides of the abortion debate. While I certainly understand the political landscape and all of that, Mr. Payne immersed me in a life I don’t want to inhabit: that of a person whose only goal is to get their hands on some spray paint.

Further, Ms. Chase addresses an occasional problem of first person narration in a graceful manner. Think about it: how many times have you read a first person narrator representing a character who isn’t very smart or eloquent…but the story contains beautiful turns of phrase and features flawless craft? If you’re doing “Flowers for Algernon,” it’s really hard to pop in some Harlan Ellison/Ray Bradbury sentences. (Especially during the sections early in the story…and late.)

But gosh, Ms. Chase offers us some underline-worthy turns of phrase and powerful images:

I pushed a chair to the cupboards and climbed onto the countertop. Two glass flutes for my parents, and for myself a plastic version I’d salvaged from last New Year’s, the first time I’d been allowed, and encouraged, to stay up past midnight and seen how close the early hours of the next day were to night.

“Take a good look at that pie, Mary.”

The crust was golden brown, its edges pressed with the evenly spaced marks of a fork prong. Sweet red berries seeped through the three slits of a knife.

“It’s perfect,” she said, with her usual ferocity.

“Of course, he’ll probably let you go back soon. He’ll want you to. That’s what Mr. Middleton told us—that he admired your mind. He said he could tell you’re a very bright girl.

“I should be so lucky,” she added darkly. “Your father only saw my strength.”

Here’s the (prospective) problem: the story is being written by the seventeen-year-old narrator. A young lady who, we discover, was taken out of school at nine. Who was bright at nine, but isn’t depicted as being a huge reader. Why aren’t we jarred from the story when we read the highlights of the story?

Well, Ms. Chase is careful to point out that Mary Ellen is seventeen when writing the story. This happens in the first second paragraph. (And it’s the last sentence of the paragraph, so it stands out all the more.) Ms. Chase makes it clear that Mary Ellen doesn’t go to school, but does have a tutor that allows her to become educated while fulfilling her wifely duties. We don’t mind that Mary Ellen is such a beautiful writer because she seems very smart and interesting; we’re told Mary Ellen is an apprentice of sorts in her husband’s business and we’re sure the woman can pick up just about anything. Ms. Chase also benefits from perhaps the writer’s greatest gift: readers want to suspend disbelief…within reason.

What Should We Steal?

- Leave your morality at home. Look, we’re ALL against preteens getting married. You’re preaching to the choir. Just tell us a cool story about what happens in a world in which people DO disagree with us.

- Layer in the crazy like and don’t apologize. It’s your job as a storyteller to tell tales we haven’t heard before about exceptional characters. Think of your reader like the proverbial frog in the pot: turn the heat up slowly and we won’t even notice until the water is boiling.

- Ensure that your narration fits your narrator. Odds are that your five-year-old narrator is not going to whip out a reference to War and Peace. Just saying.

Short Story

2007, Alexander Payne, Best American 2008, Jim Taylor, Katie Chase, The Missouri Review, tone

Video

GWS Video, Lee K. Abbott, Sarah Yaw

Title of Work and its Form: “Bravery,” short story

Author: Charles Baxter

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the Winter 2012 issue of Tin House and was subsequently chosen for Best American Short Stories 2013.

Bonuses: Here is an interview Mr. Baxter gave to Bookslut. Here is what Karen Carlson thought of the story. Mr. Baxter is the author of Burning Down the House, a fantastic book about writing craft. (Well, Graywolf only publishes fantastic books.) Mr. Baxter discusses the book in this interview with The Atlantic.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: White Space

Discussion:

This is, in a way, the story of Susan’s coming of age. We meet the young woman as a teenager who, unlike her friends, is attracted to men who are, above all, kind. Susan affirms her interest in college and finally meets Elijah, a pediatrician who devotes his time to caring for others. Before long, the two are married and on honeymoon in Prague. On one eventful day, the pair walks through a chapel whose walls are filled with carved babies. An omen? Then the pair are verbally accosted by a woman who shouts at them in angry Czech. An omen? Then Susan is grazed by a tram. An omen? These must have been omens, as Susan immediately finds herself pregnant. The last scene of the story finds Elijah feeding the baby. Susan insists he stop, whereupon Elijah goes on a walk that results in a thematically relevant experience.

There are a lot of eternal struggles for those who take up the challenge of storytelling. One of them is how to use white space and their asterisky cousin: the section break. When should we use white space? Unfortunately, there’s no absolute right answer. Like any other choice, white space creates an effect and it’s our job to decide if we’re creating the proper effect. Mr. Baxter uses white space in “Bravery” for many of the common reasons:

- To jump ahead in time.

- To emphasize a single image or experience. (Susan’s tree dream.)

- To afford him the chance to get in a cool end-of-section “punch.”

- To allow that “punch” to land and to reverberate in the reader’s mind.

- To control how fast the reader reads the story and the path of his or her eyes.

Mr. Baxter uses two asterisk section breaks in the story:

- After Susan and Elijah have met and Susan reflects upon his kindness.

- After the significant day in Prague; Susan-though she is unaware-is about to be pregnant, and her dream confirms much of what she believes about her “destiny.”

If you’re anything like me, you are wondering why Mr. Baxter put the section breaks where he did. The first section break seems to have the following effect:

- Mr. Baxter spends the first few pages running through a wide swath of Susan’s life. The asterisk lets us know that the narrator is going to slow down and that the next few pages will zoom in on a very brief period of time.

- Mr. Baxter seems to be whispering, “Okay, friend. I’m done shooting tons of exposition at you! Now that you know the basics, let’s go deeper into Susan’s thoughts and experiences!”

- The transition itself mirrors the journey being taken by the characters. Susan and Elijah are on a plane. This is down time. The couple left terra firma in one place and their lives resume in another. The story functions the same way. (The asterisk is an airplane in a way.)

The second section break functions thus:

- Mr. Baxter marks Susan’s transition from childlessness to parenthood.

- Mr. Baxter zooms ahead in time from one significant scene to another.

- Mr. Baxter switches between abstract poeticism and efficient exposition. (“They named their son Raphael…”)

So how should we use white space and section breaks? Sigh…there’s no easy answer. We just need to follow Mr. Baxter’s lead and make sure that our choices have the desired effect in our readers.

Another concept with which we always wrestle is the personality of our narrators. “Bravery” has a pretty straightforward third person limited to Susan’s perspective. There’s nothing wrong with the narrator; it’s your tried-and-true reporter. I did find significance in a sentence that arrives a few pages into the story:

He handed her a monogrammed handkerchief that he had pulled out of some pocket or other, and the first letter on it was E, so he probably was an Elijah, after all. A monogrammed handkerchief! Maybe he had money. “Here,” he said. “Go ahead. Sop it up.”

The bolded sentence is significant to me because it sounded as though the narrator was speaking in a different register. The sentiment seems to suggest a lot about Susan because it’s buried in the middle of “normal” stuff. Think of it this way. Let’s say you ask your significant other how his or her day was and you hear the following:

“Eh, just a normal day. I went to the post office, then I picked up some dog food. I was a couple minutes late to work, but it was okay. I had leftovers for lunch. I ran into my celebrity crush and we went on a long walk alone in the woods. I forgot to get gas on the way home, so I have to do that tomorrow morning. That’s about it.”

I’ll bet I know which part of that list you’ll ask more about! The extraordinary (in this case suspicious) sentence stood out among the rest. “Maybe he had money” stood out for me because it seemed different from the narrator’s other thoughts and shaped how I understood Susan to some small extent.

What Should We Steal?

- Employ white space and section breaks to create the desired effect in your reader. Most readers aren’t going to mark up your stories with a pen and wonder why you did what you did. They are going to absorb these breaks subconsciously.

- Spice up your narrator as carefully as a chef spices a dish. If your narrator is that traditional laid back third person limited, you probably shouldn’t jazz things up TOO much. But a little bit of jazz? That can make your story pop.

Short Story

2012, Best American 2013, Charles Baxter, Tin House, White Space

Title of Work and its Form: “Never Write From a Place of Despair,” creative nonfiction

Author: Erika Anderson (on Twitter @ErikaOnFire)

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece debuted in Issue 1 of Midnight Breakfast. You can find the work here.

Bonuses: Ms. Anderson is very kind; she offers a collection of her publications at her web site. I particularly enjoy her brief “workshop” of the author photo.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Momentum

Discussion:

This work of creative nonfiction describes Ms. Anderson’s reaction to the aftermath of her divorce. It seems clear that Ms. Anderson was figuring things out at the time and that the piece is an instance in which the author is giving the reader advice that she is also trying to internalize. There are many “rules” in the piece, several “do not”s and “never”s and the final paragraph leaves us with a sense that catharsis is on its way, albeit slowly.

I was first struck by the momentum in the piece. Ms. Anderson grabs you by the lapel and won’t let you go. How does she make this happen? Well, repetition for one thing. A composer uses motifs, short melodic passages, to bring unity and momentum to a piece. Plenty of examples can be found in the best music ever composed:

Ms. Anderson establishes the “never write” motif in her title and employs it in the piece. She eventually brings in “do not,” just as Beethoven cleverly introduces the famous “Ode to Joy” melody to the symphony before he allows it to take over the work and reach full flower.

Ms. Anderson does another thing to build and maintain momentum: she varies the lengths of her paragraphs, just as Beethoven varied the tempi in the movements of the Ninth.

I also admire the manner in which Ms. Anderson confronts one of the big problems inherent in the composition of creative nonfiction: YOU HAVE TO BE HONEST AND SOMETIMES REVEAL SOME OF THE FAILURES OF YOUR LIFE OR THINGS THAT ARE A BIT EMBARRASSING.

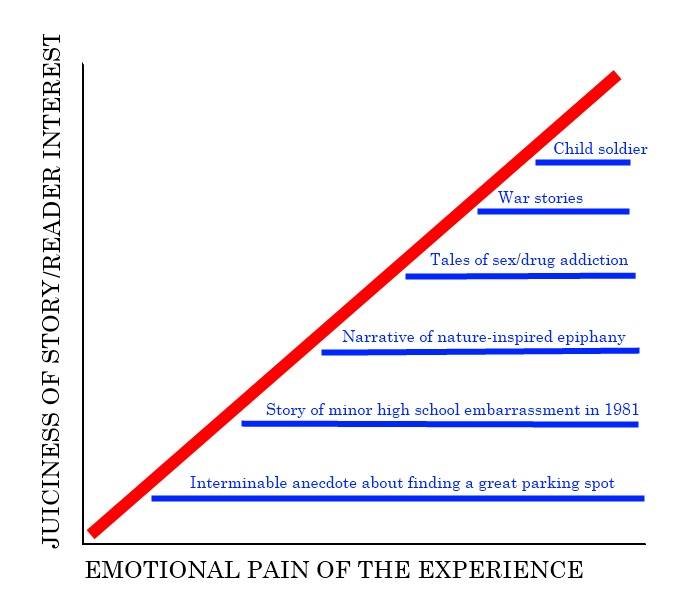

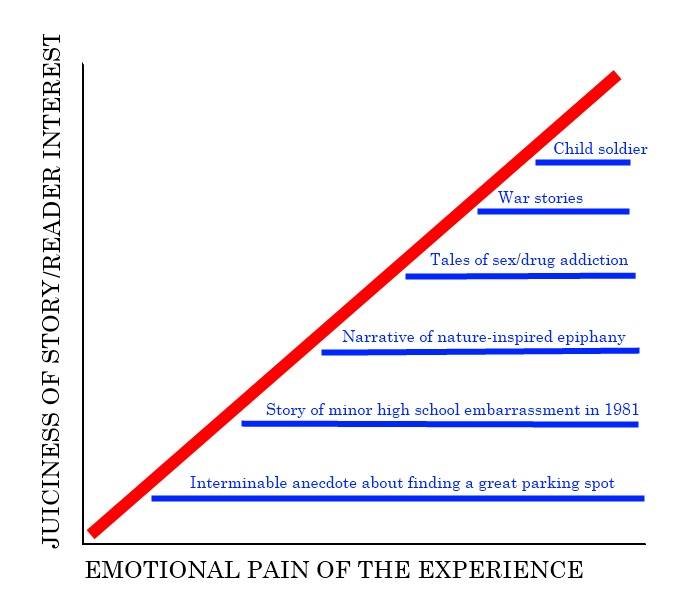

Sad but true: our lives don’t always unfurl according to our plans. We will sometimes fail in our efforts and our relationships. Unfortunately, these are the kinds of truths that we must confess in creative nonfiction. Happy stories are often meaningless or boring. Divorces? They’re usually as painful as they are “juicy.” Think about it this way. Let’s say you’re on a bus and I plop down in the seat beside you and say, “Boy, do I have a story for you. This one time, I stubbed my toe so bad that it swelled up and looked like a grape for a MONTH.” And then I keep talking about it for an hour. You’d go crazy, right?

Now let’s say that Valentino Achak Deng sits beside you and somehow organically mentions that he’s one of the Lost Boys of Sudan. I’m going to bet that you would be interested in hearing his story, even though that story is ridiculously sad and should never, ever happen in reality.

I think my ultimate point is that we NEED to confess and to bare ourselves in order to create powerful works of creative nonfiction. There may certainly be exceptions, but we spend our lives surrounded by people who hide behind projections of how they want to be seen by others. Writers such as Mary Karr are brave enough to expose their flaws. Not only are her stories more interesting than most, but they’re also more powerful.

Here are my thoughts in chart form:

Ms. Anderson’s story definitely doesn’t fall on the bottom of the red line. You don’t have to be Harold Bloom to pick up on the fact that Ms. Anderson is telling us that she was in that “place of despair.” She reveals that she may not have known her ex-husband as well as she thought. She’s brave enough to confess that she was adrift in her thirties…not the best situation, for sure.

Ms. Anderson’s story definitely doesn’t fall on the bottom of the red line. You don’t have to be Harold Bloom to pick up on the fact that Ms. Anderson is telling us that she was in that “place of despair.” She reveals that she may not have known her ex-husband as well as she thought. She’s brave enough to confess that she was adrift in her thirties…not the best situation, for sure.

It seemed to me that Ms. Anderson was being very honest with the reader, but was also employing a technique that allowed her to be frank with us. She gains distance from us through her use of point of view and choices of words. For example, here’s a passage from the piece:

You thought your husband never loved you because he could never touch you the right way. He hated that there was a right way — he wanted to pet you like a puppy, to paw at your blonde-haired forearm, to stroke the heft of your thigh, for that to be good enough. But it wasn’t, and that broke him and it broke you.

We have been told the story is nonfiction, so we assume it to be true. Ms. Anderson, however, employs the second person point of view. Why not use first person? She’s writing her own story, after all! Well, the second person allows the writer to push the reader away a little bit. We can “trick” ourselves into believing that we’re not really confessing our own problems…we’re writing about the reader’s life, right? See? It says, “You!” That means the reader! Compare the above passage after a transformation into first person:

I thought my husband never loved me because he could never touch me the right way. He hated that there was a right way — he wanted to pet me like a puppy, to paw at my blonde-haired forearm, to stroke the heft of my thigh, for that to be good enough. But it wasn’t, and that broke him and it broke me.

The sentences read differently, don’t they? The second person offers a layer of psychological protection and it also subtly turns the reader away from thinking that you might simply be complaining or laying down a list of grievances. (Not that I think Ms. Anderson is doing those things, of course.) Instead, Ms. Anderson subconsciously forces the reader to immerse him or herself in her experience. There’s no PROPER point of view for creative nonfiction (or any piece), but the point is to create the conditions under which you can tell the most faithful version of your story. If you need to switch POV, so be it.

What Should We Steal?

- Employ motifs and changes of pace to maintain narrative momentum. A speaker uses the inflection of his or her voice to keep people interested. The same principles apply to writing…just in different ways.

- Accept the fact that writing great creative nonfiction may require you to tell people your dark secrets. Everyone has a walked-out-of-the-bathroom-with-toilet-paper-stuck-on-shoe-on-a-first-date story. You may have to plumb a little deeper if you want to tell a story that will capture your reader.

- Make any changes you need to ensure you put down an honest and powerful version of your true story. I wrote a brief CNF story about something sad that happened to me when I was a kid. I simply told the true story in the form of a pulp detective short story. On the off chance it ever gets published, perhaps I’ll explain my reasoning.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Beethoven, Erika Anderson, Midnight Breakfast, Narrative Momentum