Sarah Yaw’s You Are Free to Go and the Battle Between Exposition and Scene

Friends, Sarah Yaw is a longtime friend of Great Writers Steal. If you haven’t already done so, check out the story of hers that I reprinted. First published in Salt Hill, “Stepping Down” is definitely worth a read. You can also learn a lot about writing from her story.

We are here today, however, to take a look at her excellent first novel, You Are Free to Go, a book that won the 2013 Engine Books Novel Prize. (By all means, purchase a copy from the publishing company itself. Amazon is also happy to sell you a copy.)

I had the pleasure of reading the book before its official release, and I was impressed by the skill with which Ms. Yaw created the world of Hardenberg Correctional Facility and how fully she described the lives of those within its walls. Ms. Yaw also takes the next natural step and communicates the meaning Hardenberg has for those who love its inmates. This “intriguing debut” begins with a close focus on Moses, an appropriately named character who is accustomed to the weariness of his long prison journey. Moses, like most other characters in the book, is shaken when fellow inmate Jorge hangs himself, making permanent the absence felt by his daughter, Gina.

As you can tell from that description, You Are Free to Go has a lot of heavy lifting to do. There are a few complicated settings, including the prison and New York City, and characters who simply can’t and won’t interact with each other. (Corrections officers in federal prisons are pretty firm on that no-one-gets-in-or-out-without-permission thing.) As I thought about what I would say about the book, I kept thinking about how Ms. Yaw balanced the big requirements she had at the beginning of the book. She had to:

- Release a ton of exposition about the prison and the people inside. We need to know all about Jorge in order to feel something upon his death. We must also know about the prison hierarchy and Moses’s ambitions and a good deal about how the prison operates.

- Release a good bit of exposition about Gina and her life in New York City. Gina’s doing very well for herself, though she has plenty to work through. She also has the requisite number of acquaintances, some of whom we must learn about.

- Keep us interested in reading further by ameliorating the affect of her exposition drops through the use of scenework.

It can be very hard to know how much “telling” and how much “showing” we can and must do at the beginning of a work. For example, Jorge is not just going to look at Moses and say, “It’s so great that my daughter went to Brown and has an apartment on the Upper East Side.” No, that’s work for Moses to do in league with the third person narrator.

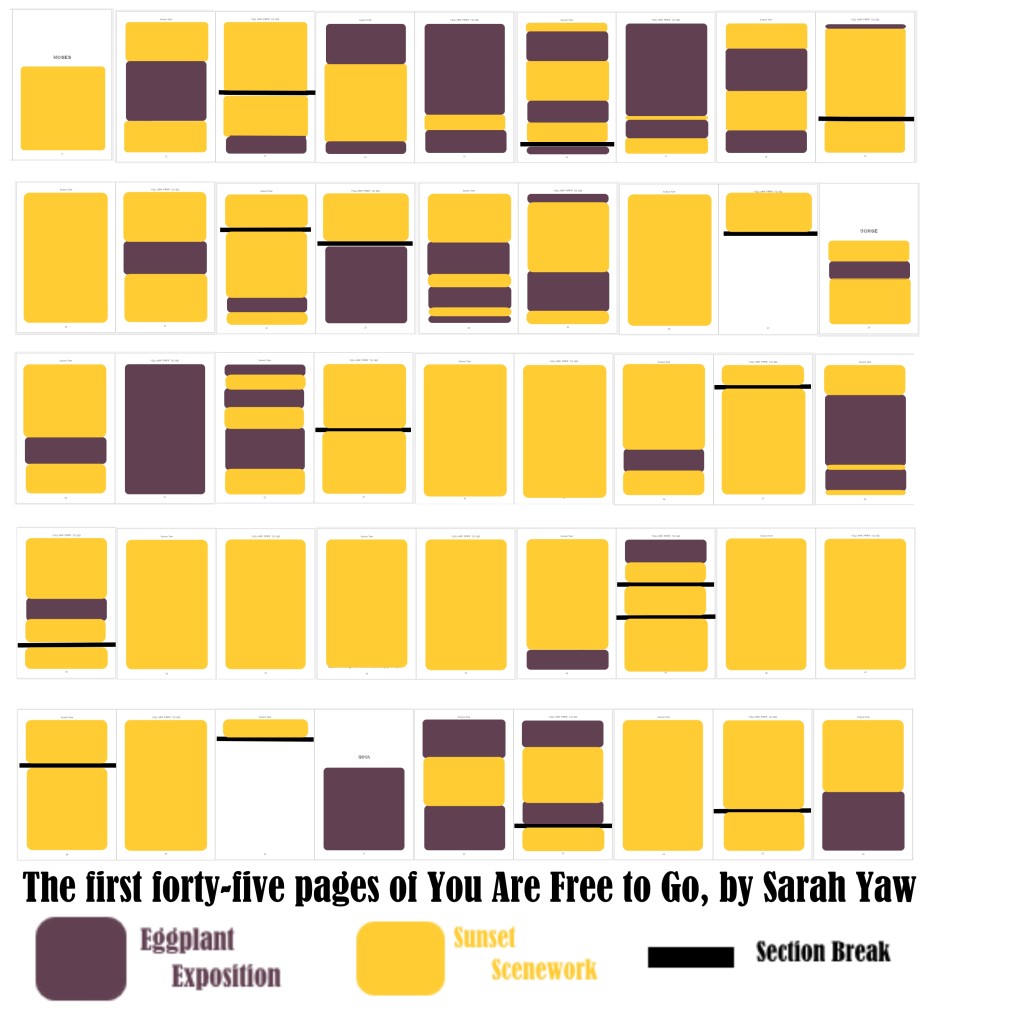

I thought it might be fun to look at the balance between exposition and scene work in a visual manner. In that spirit, I pasted together images of the first 45 pages of You Are Free to Go. The present-tense Scenework is colored in Sunset, and the Exposition is in Eggplant. Take a look:

Isn’t that interesting? Now, there’s always going to be some bleedthrough. Perhaps the narrator released a stray bit of exposition in the middle of a page of dialogue. But what do we notice? How did Ms. Yaw balance the need to tell us things with the need to keep us interested?

- She began the novel in scene. Moses is beginning his day’s work in the mail room. Yes, Ms. Yaw must fill in a lot of information, but instead of TELLING us about Moses, she puts him in contact with Lila and we have some actual drama to care about instead of a great big ball of exposition.

- She drops those big eggplant-colored bombs of exposition (tales from the past, simple explanations) after we already know about Moses and care enough to accept the exposition.

- She makes an interesting turn around page 22. Look how the scenework overwhelms the exposition. One of the scenes is nearly five pages long! All of that is present-tense work that builds the characters and SHOWS us what we need to know about the prison.

- She repeats the formula at the beginning of each chapter. Scenework with a little exposition sprinkled in…then some nice, thick scenes.

I suppose what we can learn from such an exercise is a reinforcement of the oldest writing advice around: show, don’t tell. I guess I sometimes notice a lot of telling in some of the stories I read; perhaps this is why I’ve been wondering if we’re lecturing too much in literary fiction.

The big lesson is to establish your characters as quickly as possible and then let them live their stories.

Here’s an appropriate example. In 1994’s The Shawshank Redemption, writer and director Frank Darabont uses the credit sequence to establish the exposition: ANDY DUFRESNE WAS FALSELY CONVICTED OF KILLING HIS WIFE AND HER LOVER. HE IS GOING TO SHAWSHANK.

With that exposition out of the way, Darabont introduces the other characters: Red, Warden Norton, Byron Hadley, Brooks Hatlen. Darabont is successful enough in his showing, not telling that we care very deeply about what would otherwise be an incredibly boring scene. No one wants to watch prisoners tar the roof of a building for four minutes. But everyone wants to watch Andy Dufresne regain some of his dignity and earn the respect of the others on the tarring crew, some of whom didn’t particularly like him. (There’s an added bonus in that Andy’s facility with numbers springboards the plot.)

After turning the opening of Ms. Yaw’s novel into an art project, I started to wonder what would happen if I did the same thing to one of my own stories. What would the balance look like?

“Houdini’s Knife” is one of the debut titles from Great Writers Steal Press, and I actually think it’s pretty good. (I usually hate my work.) I’m publishing work that I believe will appeal to a wider audience than most literary stuff. (You Are Free to Go is another example; I can picture my father enjoying the book.) Wouldn’t it be nice if we could break out of the writers-writing-for-other-writers doldrums and reclaim the proverbial “woman on the bus?”

You’ll forgive me for offering you a link to the Great Writers Steal Press website: readingisnothomework.wordpress.com/ See? We need to convince more non-writers that reading is not homework.

You may also enjoy the way I’m experimenting with how we market short stories. See what I did for “Houdini’s Knife?” Maybe you pick up a copy. Why not?

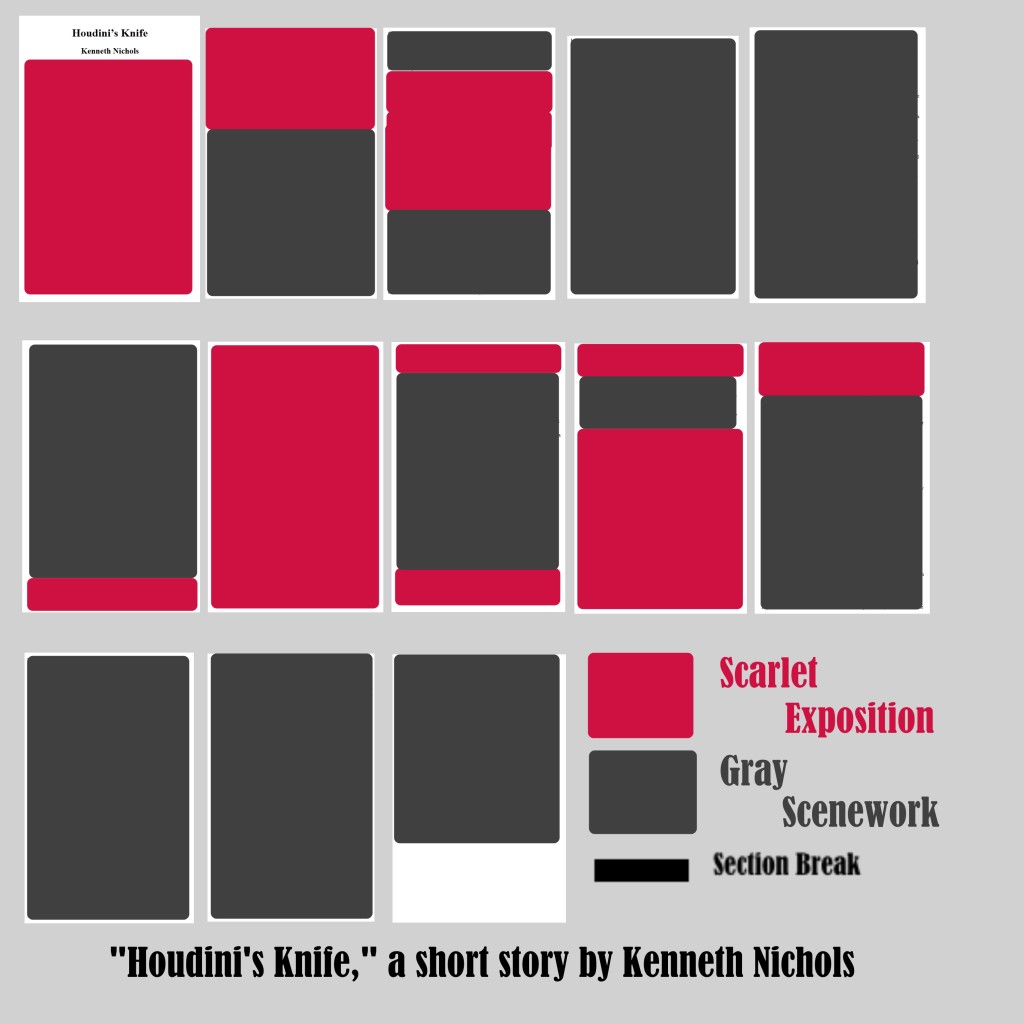

Back to analysis. I gave my story the same treatment as I did You Are Free to Go. In case you didn’t know, I’m a Buckeye. The exposition is in scarlet and the scenework is in gray.

Now, “Houdini’s Knife” was consciously composed as a kind of biography of an eighteen-year-old guy. (I deliberately omitted section breaks in an attempt to keep momentum flowing in the narrative.) The story begins with exposition; I had to reveal that Raymond’s father was a mason. The father died. Raymond was adopted. Raymond got into magic. Raymond has a crush on Becky Brennan. But look!

I did the same thing Ms. Yaw did! I had to tell you a lot about Raymond and his circumstances before I could describe Raymond doing magic tricks. You have to care about Raymond before you care about his chat with Becky Brennan. And once all of that boring exposition is out of the way, I can hit you with the appropriate and compelling ending. (Don’t worry; I don’t usually feel good about anything I write.)

What happens if you give your stories the same treatment? What are some interesting outliers that violate this structure, but are still incredibly compelling? Most of all, isn’t it interesting to think of narrative in a different way?

Reminder: You Are Free to Go is available in all fine independent bookstores, from Barnes and Noble, from Amazon and from Engine Books. You can find more about Sarah Yaw at her website and can say hello to her on Twitter.