There are couples like Ronnie and Della Black in every small town; this one happens to be Goldengate. A young man and young woman fall in love or something like it and create children who become a happy burden. Husband and wife do the best they know how, but they are increasingly alienated by time and worries about money and the increasing feeling that they determined the course of their lives too early. In Late One Night, Lee Martin turns his perceptive and empathetic eye on such a couple and the fire that ends and changes the lives of countless denizens of Goldengate.

Mr. Martin, whose excellent 2006 novel The Bright Forever earned him a Pulitzer Prize nomination, once again offers the reader a generous look into the hearts and minds of people who are often overlooked or whose perspectives are ignored outright. It’s not a spoiler to reveal that what happened late one night is a fatal fire that claimed the life of Della Black and three of the seven Black children. Wayne Best, Laverne Ott and the other townspeople were already dubious about Ronnie…did you hear? He left his wife and all those children to take up with young Brandi Tate, who’s already carrying his baby. Ronnie receives even less sympathy when it becomes clear that his car was seen was speeding away from the scene just as the fire started to burn.

Late One Night is not as much a procedural mystery about a possible arson as it is a deep exploration of the aftermath of a great and permanent sadness and the flawed person who may have been responsible. Like his other works, the book draws upon one of Mr. Martin’s strengths as a writer: the ability to humanize characters who may otherwise be granted little mercy.

We would all do well to take this lesson to heart. Whether you’re writing about a man who may have killed his wife and most of his children, or may have inappropriate feelings (as in The Bright Forever), or an old man who may be responsible for the death of his best friend fifty years ago (as in River of Heaven), stigmatized characters deserve to be humanized, not dehumanized. The general population is often reductive and simplistic with regard to society’s outliers, but writers do not have that right. Have we all committed the kind of sins that inspire Mr. Martin’s novels? Of course not. We are, however, not the same in the dark as we are in the light and we seek out people who are kind enough to see us for who we are on the whole.

How much should you tell the reader, and when should you tell them? It’s never easy to say, but Late One Night offers powerful lessons to help writers solve this dilemma. Mr. Martin begins this novel with a brief interrogation scene. In Chapter 1, Sheriff Ray Biggs asks Ronnie to unravel the mystery that has been on countless lips across Illinois since the news of the fire broke: “You better start talking…you better tell me something I’ll believe.” So we know that something truly awful has happened. In Chapter 2, Mr. Martin takes us back to the trailer fire. In Chapter 3, Mr. Martin goes back even further in time to introduce us to Della and the kids. The author continues this trend, filling his precious page space with the details of the life that Della and Ronnie shared. What do we know almost immediately? Della and at least a few of the kids are dead or at least very, very seriously injured. Do we need any more information at this point? No. Perhaps the biggest reason is that we don’t yet care about Della and the kids on anything more than a surface level. Mr. Martin tells us the story of the dissolution of the Black marriage so we will be emotionally invested in their fates and the way what happened Late One Night reverberates through Goldengate. Mr. Martin is telling us, in effect, that a character’s death is not as important as the life that he or she led.

Everyone who has ever lived has death in common. Someday, we will each breathe our last, speeding our reversion to dust. What is much more important? Much more interesting? What happened between birth and death, not the circumstances of either. Mr. Martin ensures that his focus is properly placed.

Speaking of focus, Late One Night is also contrived to play to another of the author’s strengths: character development. Now, the plot of the book chugs along at a pleasing pace and I was always curious what would happen next, but it seemed to me that the book’s plot was, in a way, released through character. Because Mr. Martin devotes so much time to immersing us alongside the people of Goldengate, the reader begins to wonder about characters in the same manner they usually do about plot. In this way, the inherent questions we have about the plot are placed alongside those we have about character. For example:

PLOT: How did the fire start? Was it an accident? The baby inside Brandi Tate is growing full speed ahead; how will the new child complicate matters?

CHARACTER: Will Captain and Shooter ever reach the kind of understanding about each other that fathers and sons deserve? Laverne Ott seems like such a decent person…how will she feel about what happens to the remaining Black children? Gosh, Ronnie and Della had such an unhealthy relationship and now the latter is gone; is Ronnie a terrible human being, or is he just a product of his circumstances? She may have been a teensy bit of a homewrecker, but is Brandi all that bad?

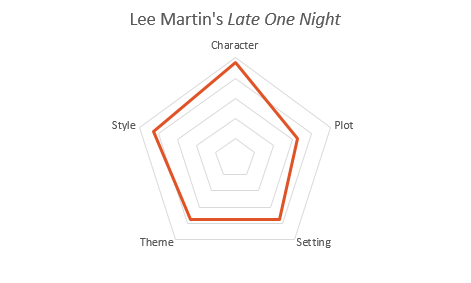

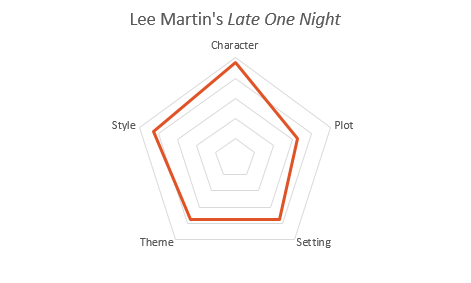

See how these separate and equal qualities of writing drive the reader forward? The overall point is that the writer has an obligation to give the reader reasons to continue. We can fulfill this obligation in a number of ways. If the setting of our story is not very compelling, then we must make the other elements of fiction more compelling. Here’s a wholly unscientific chart gauging how much Mr. Martin privileged each element of fiction:

Of course, I liked the plot very much and advise you to pick up the book, but Late One Night is not a whiz-bang action thriller like Transformers 11: Tin Man’s Revenge. That film, in turn, will have put very little emphasis on character, setting and theme…which makes sense; do you watch a Transformers film to see where Shia LaBeouf or Mark Wahlberg are on their life journeys? Nope. The writers and directors of those films pack the screen full of style and plot to maintain your attention in the same way a clicker attracts the attention of your puppy. Mr. Martin uses the right tools in the right stories to please his audience.

Having just finished my own far inferior novel, I’ve devoted a great deal of thought as to how I should begin each of the brief chapters that tell my character’s story. But gosh, isn’t it hard to begin and end each chapter with a powerful and true statement about human existence that also keeps your narrative humming? Let’s take a look at the opening sentences of the seven chapters of the book:

1: Ronnie swore it was talk and nothing more.

2: Della and the kids-the oldest fourteen, the youngest still a baby-lived in a trailer just south of the Bethlehem corner.

3: Earlier that evening she’d scooped the hot ashes from the Franklin stove into a cardboard box.

4: Della, nor anyone else for that matter, had any way of knowing that a few weeks before the fire, Shooter had forced himself to go through more of his wife’s things, a task he’d been doing a little at a time since she died back in the spring.

5: The trouble between Ronnie and Della came to a head one evening in early September when she showed up at a Kiwanis Club pancake supper with her long blond hair hacked off and ragged, tufts of it sticking out from her head and hanks hanging down along her slender neck.

6: In his heart Ronnie often felt all scraped out and empty over the way his life with Della was-too much want, too much lack, too much desire running up against the no-way-in-hell of it all.

7: By Thanksgiving, Della’s hair was growing back.

Will you excuse me if I pat my own back? Look how strong the focus on character is in each of these lines. It’s very clear that Mr. Martin wants us to get to know his subjects very well. Just as importantly, these first lines slam us into the “mystery” about the fire (1, 2, 3, 4) and inform us about the crucial relationship between Ronnie and Della (5, 6, 7) and immerse us in the Goldengate community (1, 2, 4, 5, 7). I think the important lesson here is that first lines should not be mere throat clearing that delays the narrative. Even if your creative work is bigger on setting than plot, you need to give the reader some reason to continue, something that Mr. Martin does with expertise.

If you haven’t yet read Late One Night, you have my assurance that I have not ruined any of the beauty or big surprises in the work. Mr. Martin’s restrained and gorgeous prose is a joy in itself. Like much of the author’s work, this book makes you think about the people around you in a different way. Instead of serving as mere extras in your own life, those people sharing the diner counter with you, walking beside you in the park…they are real human beings who invariably lead complicated lives and we do well to embrace the depth of the humanity found in others instead of making the easier choice to languish in a dark realm filled with shallow stereotypes.

Note: In addition to being a great writer, Lee Martin is also a very generous teacher. If you are also a wordsmith, please consider following his Facebook group. In addition to informing you about his own work, he links to his very useful blog posts. He also has the Twitter (@LeeMartinAuthor). Don’t we live in fascinating times?

Novel

Dzanc Books, Late One Night, Lee Martin, Ohio State

Title of Work and its Form: “”In the style of Joan Mitchell”,” poem

Author: Janelle DolRayne

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem debuted in the October 2014 issue of inter | rupture. You can find it here.

Bonuses: Here is an apt poem that was subsequently chosen for Best of the Net 2013. Here is a reading list that Ms. DolRayne put together in her capacity as Assistant Art Director for Ohio State’s The Journal. Want to see the poet read her work?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Conceits

Discussion:

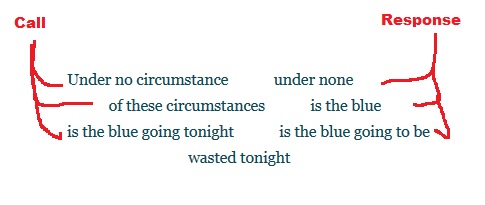

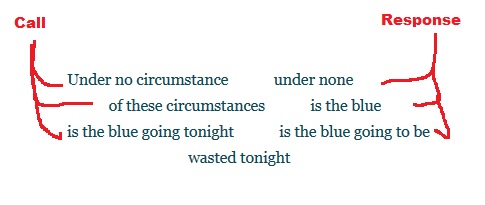

Ms. DolRayne offers us a poem with a fun and interesting conceit. (It bears mentioning that Ms. DolRayne may not have the same idea as I do about her poem…but that’s okay.) It seemed to me that the poem is a powerful attempt to use poetry to mimic the loose and quietly powerful feel of a folk song. If you’ll notice, the first few stanzas feature lines that employ the call-and-response technique popular in folk, blues and rock music:

You’ll also notice that the last stanza abandons the conceit, which is perfectly fitting. The narrator of the poem is now speaking in “unison” or “a cappella.”

You’ll also notice that the last stanza abandons the conceit, which is perfectly fitting. The narrator of the poem is now speaking in “unison” or “a cappella.”

First, I’ll give you some examples of the call and response I’m talking about. Phil Medley and Bert Berns wrote “Twist and Shout,” a song that was covered by a lot of groups, including The Beatles. You’ll notice that the background vocalists mirror and augment the lead singer.

Steven Page and Ed Robertson wrote “If I Had a Million Dollars.” As I understand it, Ed had written the bulk of the song, but only had his part of the vocal. Mr. Page heard the song in progress and added his part. Mr. Page sometimes simply repeats Mr. Robertson’s part; sometimes he adds to the narrative of the song and takes it in a new direction.

The response doesn’t even have to come from a vocalist. In George Thoroughgood’s “Bad to the Bone,” the response comes from guitar and saxophone.

I loved Ms. DolRayne’s use of this technique for a number of reasons:

- Poetry is just a kind of music, right? Why not make that connection explicit in this way? Some people think poetry is a fancy-pants thing you read because some teacher told you to. Those same people love music without realizing poetry does many of the same things.

- The “call and answer” adds another voice to the poem, even though it’s only being written by one author. In this way, we’re able to produce a kind of harmony.

- The images and ideas in the poem are reinforced through repetition and through being conceptualized in a different way.

- The phrases on each side of the large spaces can be considered poems unto themselves and these poems are in conversation with each other, aren’t they?

One of the inherent difficulties in writing is bridging the gap between thought and the written word…and trying to figure out how to combine words, space and punctuation in such a way that the reader will understand the thought you had. Ms. DolRayne literally adds in the pauses that led me to treat her poem like a kind of song. For the poet, those pauses are spaces between words. For a singer, those pauses are bits of silence between musical phrases. Why not take Ms. DolRayne’s idea and try to lay down some prose in the style of a musician?

I think one of the reasons that I identified the call-and-answer conceit in the poem is because the poem was challenging me, inviting me to make sense of it in a way that made me happy. If you’re near a window, look out at the clouds. What shapes you do see? A phenomenon called “pareidolia” forces us to make sense out of “vague or random” stimuli.

Now, that’s not to say that Ms. DolRayne has given us a poem filled with randomness, because she didn’t. That’s writing craft in a nutshell, folks. The poet had to work very hard to create a work that clearly communicated her own thoughts while ensuring the piece was open enough to allow the reader to draw his or her own conclusions.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy method by which writers can learn to be simultaneously specific and vague. That’s just not something you can learn with a step-by-step procedure. Instead, we just need to read a lot of poems and write a lot of poems and hope that our skills improve to the point where we have the power to turn any trick we like.

What Should We Steal?

- Think of yourself as a songwriter when you compose. The conventions of music are not exactly the same as the ones writers use, but we can use their prose equivalents to our advantage.

- Trigger your reader’s pareidolia. How can you get your reader to see the plan in what seems like randomness?

Poem

2014, Conceits, inter|rupture, Janelle DolRayne, Ohio State

Show Notes:

Enjoy this interview with Wendy J. Fox, author of The Seven Stages of Anger, a short story collection published by Press 53.

Purchase The Seven Stages of Anger:

http://www.press53.com/bioWendyJFox.html

Find out more about Wendy J. Fox:

http://www.wendyjfox.com/

Visit the web site of BookBar:

http://www.bookbardenver.com/

Like the bookstore on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/BookBarDenver

Book You Should Buy: Backswing by Aaron Burch

http://www.queensferrypress.com/books/backswing.html

Find out more about Aaron Burch:

http://aaronburch.tumblr.com/

Better Know a Buckeye: Allison Davis

http://www.allisondavispoetry.com/

http://www.greatwriterssteal.com/2013/09/04/gws-essay-how-to-and-how-not-to-steal-writing-about-animals-by-allison-davis/

Purchase Ms. Davis’s book:

http://www.kentstateuniversitypress.com/2012/poppy-seeds/

Website: http://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Short Story Collection, Video

Aaron Burch, Allison Davis, Backswing, Carrie White, Ohio State, Press 53, Wendy J. Fox

Enjoy this interview with Jac Jemc, author of A Different Bed Every Time, a short story collection published by Dzanc Books.

Purchase A Different Bed Every Time:

http://www.dzancbooks.org/our-books/a-different-bad-everytime-by-jac-jemc

Find out more about Jac Jemc:

http://jacjemc.com/

Show Notes:

Visit the web site of Women & Children First:

http://www.womenandchildrenfirst.com

Like the bookstore on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Women-Children-First-Bookstore/8326741337

Book You Should Buy: Fobbit by David Abrams

http://www.davidabramsbooks.com/

Buy the book here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/fobbit-david-abrams/1109170055?ean=9780802120328&itm=1&usri=fobbit

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780802120328/david-abrams/fobbit

Better Know a Buckeye: Erin McGraw

http://www.erinmcgraw.com/

http://www.greatwriterssteal.com/2013/01/26/what-can-we-steal-from-erin-mcgraws-punchline/

Purchase Erin’s books:

http://www.amazon.com/Erin-McGraw/e/B001ITRD0W/ref=dp_byline_cont_book_1

Website: http://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Short Story Collection, Video

David Abrams, Dzanc Books, Erin McGraw, GWS Video, Jac Jemc, Ohio State, The Great Writers Steal Experience

Short Story, Video

Laurel Gilbert, Michael Kardos, Ohio State, Star Wars, T.C. Boyle

Title of Work and its Form: “I Heart Your Dog’s Head,” poem

Author: Erin Belieu (on Twitter @erinbelieu)

Date of Work: 2006

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem appears in Black Box, Ms. Belieu’s 2006 Copper Canyon Press book. The Poetry Foundation has made the poem available on its web site.

Bonuses: Check out this great interview the poet gave to Willow Springs. Ms. Belieu also conducts interviews with poets. Want to hear Ms. Belieu read her work? (Sure, you do.)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Subject Matter

Discussion:

Poems have to be all dark and depressing, right? Don’t poems have to illuminate the author’s saddest thoughts? Appropriate subject matter for poems: romantic break-ups, deceased pets and the worst day you ever had…right?

Of course not! Poems can also be fun and can deal with any subject under the sun-or beyond. Ms. Belieu’s free verse poem is about her reaction to watching Bill Parcells coach a game on television. Now, the poet makes it clear she doesn’t care about football, but she understands that football, like everything else, is a chapter in the vast narrative of our society. After discussing her antipathy for Mr. Parcells, Ms. Belieu reveals her history of not caring about football despite having been born in Nebraska, one of the places where football is a particularly prominent part of the social fabric. The thought leads her to recall the barking Chihuahuas on her street. Finally, Ms. Belieu “puts her faith” in reincarnation, hoping that Mr. Parcells is someday “trapped in the body of a teacup poodle” so she can hear his yapping.

I loved that Ms. Belieu wrote a poem about a popular subject. Too many folks think that poems must be inaccessible and must deal with “fancy-pants” topics…not so! Football is the same as any other human endeavor; poets have the right to take a look at the sport with the full power of their critical acumen. I have done the same on occasi0n, writing poems for my blog on my favorite Ohio State sports site. (Why do I write poems for a community that is sport-centric? Well, poetry belongs everywhere and we shouldn’t assume that a “sports fan” doesn’t like what we do.)

The overall point is that we have permission to take on any subject we like. Football, computers, cars, Kardashians, the latest episode of Hell’s Kitchen…they’re all within our purview as artists. More importantly, we SHOULD interact with the rest of what is happening in our culture. Writers are the people who make sense of the world; we chronicle the evolution of the human soul.

Even better, Ms. Belieu doesn’t make the poem solely about football. Everything that we do means something more than is apparent on the surface, right? Just before the final stanza, she builds upon her football- and Chihuahua-related discussion. Why were those lines important? Well, they led her to think about “what’s wrong with this version of America.” She engages in cultural criticism, seeming to raise issues regarding the tribalism inherent in sport (Go Bucks!) and perhaps the obligation people feel to like a team just because their parents did. People like Bill Parcells, who she feels is happy and successful for the wrong reasons, will win the game, in spite of his sins. (Are you curious as to whether Mr. Parcells won in the game to which Ms. Belieu refers? Me too. Well, Mr. Parcells left the Jets in 1999 and returned to coaching with the Cowboys in 2003. At the time, the Giants and Jets shared Giants Stadium, part of the Meadowlands Sports Complex. The Cowboys played the Giants in Week 2 of the 2003 season. The score? Well, Mr. Parcells and the Cowboys won the game in an overtime thriller, 35-32.)

A writer can’t simply tell a story or provide his or her reader with a bare description of something; it’s our job to explain what that thing means. That single game is now pretty irrelevant, relegated to the memories of those who attended and to box score statistics. Thanks to Ms. Belieu’s insight, however, that 2003 game can still have a big effect on us. After all, we read the poem and it had some impact upon us!

I’ve been wracking my brain as to why Ms. Belieu made a specific choice in the poem. Approximately halfway through, she writes:

…of breaking a soul. Yes,

there’s the glorification of violence, the weird nexus

knitting the homo, both phobic and erotic,

but also, and worse, my parents in 1971, drunk as

Australian parrots in a bottlebush, screeching…

Look at that middle line. I love the way she condenses two words that are somewhat long and unwieldy. Instead of burdening the line with both “homophobic” and “homoerotic,” she is using language in a somewhat playful way and is inviting us to do the same. As I said, I do wonder why she cast the line that way. Why not:

knitting the homophobic and homoerotic

Well, as I said, I like the fun use of language. But why did she use commas when she could have used em-dashes?

knitting the homo—both phobic and erotic—

Or parentheses? After all, that second clause is a parenthetical statement.

knitting the homo (both phobic and erotic)

I’m certainly not criticizing Ms. Belieu’s choice; I’m just trying to understand the effect the choice has so I can use it in my work in the future. I think that the commas keep the poem flowing more fluidly than parentheses would. (A parenthetical thought might stop the reader for a moment. Didn’t this parenthetical thought stop you just a little?)

The lines that contain that fun sentence benefit from the slipperiness of the comma instead of the businesslike interjection of parentheses.

What Should We Steal?

- Empower yourself to confront any element of the human experience. There can and should be poems (and stories) about everything that has an effect on human beings.

- Add relevance to something that may seem irrelevant. I’m a big baseball fan and I love my Detroit Tigers. The Tigers play 162 games a year (not including the playoffs). It’s hard for me to remember a game a week after it’s played; the ones that endure in my memory are the ones to which I applied a special significance.

- Contrive your lines with the sounds of the words and phrases in mind. Even if you’re breaking a grammar rule or two, your higher duty is to communicate your thought to the reader in the most efficient way.

Poem

2006, Copper Canyon Press, Erin Belieu, Ohio State, Subject Matter

Title of Work and its Form: “The Things We Don’t Talk About,” short story

Author: M. Hannah Langhoff

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story made its debut in Relief: A Christian Literary Expression. You can purchase the issue in print or digital form here.

Bonuses: Here is an excerpt from a piece Ms. Langhoff published in Cicada.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

What a solid story! Rachel is a fourteen-year-old young woman who has a few problems. Not the least of which is the jerk boy who knocks her down as he rides his bicycle past her. This inciting incident results in Rachel taking Tae Kwon Do classes, where Rachel meets Mr. Cassidy, a high school black belt who teaches her how to protect herself. Rachel’s family is very religious; there is concern as to whether the martial arts lessons are leading her away from her faith. As you really should expect, Rachel learns about herself and her life in the course of the story’s events.

I guess what I love most about the story is that Ms. Langhoff employs a firm structure that makes her intent clear: she wants to tell you a meaningful story about an interesting character.

Let’s see how closely and gracefully Ms. Langhoff adheres to Freytag’s Pyramid:

Inciting Incident: Rachel gets knocked over by the bully.

Complication resulting from the Inciting Incident: Rachel starts taking Tae Kwon Do.

Complications resulting from previous Complication: Rachel meets Jacob Cassidy, a slightly older teacher at the dojang. Rachel sees Diane.

Complications resulting from previous Complications: Rachel shares a significant ride home with Jacob. Diane becomes prominent in her life.

Climax resulting from the Complications that resulted from the Inciting Incident: Rachel encounters the young man who kicked things off in the first place.

Denouement: Rachel’s actions reflect her changed character and self-understanding. Not only is she living in the “new normal,” but she has become the “new Rachel.”

See how beautifully everything comes together? Reading the story just FEELS GOOD.

Ms. Langhoff’s third person narrator is also very powerful and efficient. Check out the very first sentence:

Rachel’s walking along Smith Street, her backpack pleasantly heavy with algebra and sociology and The Call of the Wild, when she hears the buzz of wheels on the sidewalk behind her.

I love the way that the narrator establishes the present tense, the general age of the character, the specter of a threat and the protagonist’s general good-girl attitude. All in one sentence. The narrator is also unafraid to do the real work of the narrator; it skips through time and place at will:

The following Sunday is Rachel’s birthday.

And the narrator is also aware of what is happening in the mind of each character:

What Rachel’s mother doesn’t know, because of their silent agreement, is that Rachel is good.

Even if your narrator is not a “real character,” it’s still a powerful consciousness that is crafting your story. Erin McGraw, a wonderful writer and one of my teachers at Ohio State, reminded me of the narrator’s power with the phrase,

Meanwhile, back at the ranch…

Your narrator can have as much or as little power as is necessary to serve the story you wish to tell. It may also be beneficial to allow yourself to “separate” from the characters and events by thinking about the narrator as a writing partner over whom you have a lot of control.

Another part of the story that I admire is that Ms. Langhoff doesn’t tell us how to feel. Like everyone else, I’m saddened when people mistreat each other. It’s a sad fact of existence. A lesser writer (such as myself), might have enlisted the narrator in judging the sins of the characters. Judgment, however, is reserved for the reader. Ms. Langhoff’s narrator simply recounts events and thoughts, ensuring that the reader feels the power.

The principle is a corollary of “show, don’t tell.” If we follow Ms. Langhoff’s lead and SHOW the reader what is happening and what people are saying and thinking, then the reader is more likely to have an emotional reaction. If we’re TOLD how to feel, it’s probably not going to work.

Here’s a strange example. (Strange examples are more fun than boring ones, of course.) Remember that father who shot his daughter’s laptop to punish her for saying mean things about him on Facebook?

The father’s rhetorical goal was to make his daughter feel bad for not wanting to do chores and for using naughty words. How did he choose to get his message across? With the use of firearms. It seems to me that TELLING his daughter how to feel-and involving firearms-teaches a kid far different lessons. For example, “grownups solve their problems with gunplay.” A heavy-handed third person narrator may not be as effective as one that is a little more hands-off.

What Should We Steal?

- Scale Freytag’s Pyramid. Well-structured stories just FEEL RIGHT.

- Think of your third person narrator as a character with full citizenship in your story. Your narrator is a conduit, but it’s also a version of you in some way. Which strings will you, as the puppet master, choose to pull?

- Leave the analysis for the reader. Okay, we’re ALL bummed that people are sometimes unpleasant to each other. Let us decide how we will feel instead of telling us.

Fun afterthought: I’m amused that the father who shot the daughter’s laptop in an attempt to publicly shame her into behaving appropriately is upset at Dr. Phil for attempting to publicly shame him into behaving appropriately.

Short Story

2014, M. Hannah Langhoff, Narrative Structure, Ohio State, Relief: A Christian Literary Expression

Title of Work and its Form: “Aneurysm,” poem

Author: David O’Connell

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: “Aneurysm” made its debut in issue 4.1 of Unsplendid. You can find the poem here.

Bonuses: Mr. O’Connell was the 2013 winner of the Philbrick Poetry Project‘s chapbook competition. You can purchase his chapbook from the Providence Athenaeum or from Amazon. Here is Richard Merelman’s review of A Better Way to Fall from Verse Wisconsin Online. Here is “Redeemer,” a poem Mr. O’Connell published in Boxcar Poetry Review. Here is “Thaw,” a poem he placed in Rattle.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Lineation

Discussion:

Mr. O’Connell’s poem is a fairly straightforward description of a very sad event. The poem is dedicated to “P.L.,” who lived from 1974 to 2001; we assume that the young man in the poem has died during a very common rite of passage: jumping into a pool from a roof. Through fourteen lines, Mr. O’Connell communicates the sense of loss he felt and connects it to the kinds of loss that we all share.

The first thing that struck me about the poem is the way Mr. O’Connell prepares us for what the poem will do. The title? “Anuerysm.” The dedication? “for P.L. 1974-2001.” What do we learn about the poem from those two elements?

- Tone: the poem probably won’t be upbeat and carefree. Aneurysms are scary and unpleasant and we’re all pretty bummed when people die young.

- Subject matter: we assume we’re going to read an account of the young person’s death.

- Characterization: Mr. O’Connell is a character in the poem; the title and dedication make him seem like a solemn and respectful person…when it comes to this topic, at least. I’m sure Mr. O’Connell has a healthy sense of humor with regard to the appropriate subjects.

Mr. O’Connell introduces the poem in such a manner that the reader feels welcomed. While we all love writing that may be a little more opaque in its meaning, the opening of “Aneurysm” faithfully mimics the approachability of the rest of the text.

I love the way that “Aneurysm” makes use of lineation. It’s my impression that many beginning writers struggle with that jagged right margin. Ending a line is pretty easy when you’re writing prose; you just keep writing. When you’re writing a poem, knowing where to begin again is far more difficult.

Mr. O’Connell demonstrates the power of lineation. Look at the end of the first stanza:

the chimney. Sixteen, he’s on my roof

and then not. Cut by glare, his fall

So P.L. ends that first line on the roof…the reader moves his or her eyes down and to the left…and he’s no longer on the roof. The eye movement mimics the literal movement of the character in the poem. That stanza break also forces the reader into a moment of anticipation, even if that anticipation is subconscious. For that split second, we’re wondering what will come next. Let’s see how the effect would be ruined if we slapped all of the words onto the same line.

…the chimney. Sixteen, he’s on my roof and then not. Cut by glare, his fall…

See? We lose the tension Mr. O’Connell was smart enough to create.

Another great thing about the poem is the way Mr. O’Connell chooses an unanticipated and powerful verb:

the moment he explodes the pool,

Mr. O’Connell had a number of more conventional options:

- jumps

- falls into

- dives into

- drops into

- descends into

- enters

- reaches into

- slips into

Instead, Mr. O’Connell has the protagonist “explode” the pool. Not only do we get an idea of what the narrator must have looked like upon contact with the water, but we get a better idea of how the pool itself must have appeared. Even better, “explode” is a pretty heavy duty word, isn’t it?

What Should We Steal?

- Welcome the reader into the piece. The title and first lines should communicate the tone, intent and subject matter of the rest of the piece.

- Compose your lines in such a manner that you create anticipation and reflect the events of your poem. Lineation is a special instance of cognitive understanding that is shaped by physical movements.

- Employ unexpected verbs. A baseball player can “hit” the ball…or he can “knock,” “slap,” “pound,” “slam” or “drive” the ball.

BONUS BONUS:

I’m not quite sure where this fits in, but the first line of the poem reminds me of what I guess I think of as “poet meter.” Is it just me, or do you hear this meter a lot when you go to poetry readings?

It’s not quite iambic pentameter, but it has that sing-songy quality that draws you in.

Poem

2013, David O'Connell, Lineation, Ohio State, Unsplendid

Title of Work and its Form: “?,” poem

Author: Julie Danho

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem appears in Six Portraits, a chapbook published by Slapering Hol Press, the small press imprint of The Hudson Valley Writers’ Center. The kind folks at the HVWC have included the poem on the Six Portraits page to show you what you’ll find in the chapbook.

Bonuses: Here is a creative nonfiction essay Ms. Danho published in The SFWP Journal. Here is a poem Ms. Danho placed in Blackbird. Here is a poem that was published by Solstice.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Punctuation

Discussion:

What a clever and interesting poem! On the surface, Ms. Danho simply describes the humble question mark in a number of unexpected ways. The poem is a creative work, so there are, of course, infinite interpretations. Me? I think I like the idea of personifying a question. Just like a person, a question can change your life or bring you joy or simply make you think about life.

Sure, the comma helps your reader know when there’s a pause or an independent clause. The full stop splits up sentences and allows your subconscious to digest prose in a felicitous manner. Punctuation is indeed functional, but why can’t it also serve as the medium through which meaning is transmitted? Why shouldn’t we USE punctuation in more powerful ways?

.

The humble period. She can stop a sentence in its tracks. She can be the punch that drives home a confession or an insult. She can cap off an epiphany or a declaration of love. She can get together with some of her friends and form

…

An ellipsis. A pause between phone call phrases. A moment of anticipation. What happens when a question mark gives a bracket a hug?

&

The ampersand is formed. (The punctuation mark with several backs?) Inclusion. The joining of parent & child. And I can’t help but point out my twelve-year-old self’s favorite bit of “functuation:”

‽

The interrobang.

The point is that writers, like any craftsperson, should make use of every tool in his or her toolbox. How can you use punctuation in an unexpected manner that will communicate your intention without leaving your reader behind? (And let’s all thank Ms. Danho for writing a poem that makes us consider punctuation in this way?)

Another thing I love about the poem is the way Ms. Danho renders the question mark in a logical, top-to-bottom fashion. The poem begins with a consideration of the mark’s curves and ends on a consideration of the mark’s dot. I think that this choice might have been especially important because Ms. Danho’s poem does a “weird” thing. While a reader may not expect to read a work in which a question mark is personified, he or she can certainly relate to looking a person from head to toe and rendering a verdict. Isn’t this what we do when we see Michelangelo’s David or lay eyes on a blind date for the first time? (The poem may also be “accessible” because it’s told in first-person…a kind of communication we each experience every day.)

If forced to choose, I think that I would say that the “s” sound is the dominant phoneme in the poem. Why is this appropriate? Both the ? and the S are curvy. I’m not sure if Ms. Danho thought of it in this manner, but we’re her readers…we can do whatever we like. What happens when we employ alliteration and actually make use of the sounds our letters make? Great things!

I think it was Bill Cosby…I might be wrong. But I think it was Bill Cosby who jokingly told parents to give children names that end in vowel sounds. Why? Because those names allow you to yell at the kid more effectively. Think about it. Your child is late for dinner. You poke your head out the door and shout: “BRENT!” That “nt” is hard to shout and the “breh” sound may not communicate your displeasure. What about “TIME FOR DINNER, JULIEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE!” Okay, that sounds much better when shouted. Good things can happen when we consider the sound of a word with its appearance.

What Should We Steal?

- Make use of punctuation instead of just using it in the ways proscribed by textbooks. Punctuation can create meaning instead of simply clarifying meaning.

- Ensure that your “weird” work offers a handhold to the reader. Fine. Spend a thousand words describing an extraterrestrial’s biology. Maybe you keep it accessible by doing so in the format of a recipe.

- Match alliteration to the point of your work. A poem about yelling? Perhaps you’ll want to pack a lot of open vowel sounds into that piece.

Poem

2014, Julie Danho, Ohio State, Punctuation, Slapering Hol Press

Title of Work and its Form: “The Fall Forecast,” poem

Author: Shelley Wong

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem was first published in Issue 57 of The Collagist. You may read the work here.

Bonuses: Here is “In the Hot-Air Balloon,” a poem Ms. Wong published in Nashville Review. Here is an interview in which Ms. Wong discusses her poetic aesthetic and philosophy. Ms. Wong placed her poem “Self-Portrait as Frida Kahlo” in Linebreak.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Making Use of Our Interests

Discussion:

In my view, this is a poem in which Ms. Wong considers the fashion world in the context of nature. Fashion has seasons, the colors change, some elements die while other elements are born. The other great strength of the poem is the beautiful language that Ms. Wong employs, painting the image in our minds with the use of colors and unexpected words and the occasional divergence from our expectations.

Now, Ms. Wong seems to know more than I do about the world of fashion. (It’s very easy for a person to be more familiar with fashion than I am.) Whether or not she is indeed a fashion enthusiast, the poem can teach us an important lesson. I love Ms. Wong’s comparison between high fashion and the deep beauty of the outdoors. This connection is probably not one that I would have made on my own, but it’s nonetheless illuminating. This is the point of writing-and specifically poetry-to help us think about ourselves and our world in different ways.

While I’m not a fashionista, I am a baseball card…ista. I know a lot about that field and could apply it to my writing in some way. I know a little bit about fashion pens and have even done minor repairs to these functional works of art. I’m very familiar with the Detroit Tigers and with The Howard Stern Show. And the fascinating and terrifying story of Dianetics and Scientology. We all have oases of expertise that combine to create our unique worldviews. This knowledge can be put to powerful use in your work. What kind of unexpected metaphors can you create by making use of your own special knowledge?

Look at how beautifully Ms. Wong uses the phoneme sounds in the first few lines of the poem:

Each autumn the editors name the leaves

anew: burgundy, emerald, chartreuse,

and bronze. They want women to wear

Europe, gemstone, liqueur exclusively

made by monks, antique metal.

Now I’m going to make a comparison informed by my interests and passions. Ms. Wong twists and turns and twirls through different sounds in these lines. First, the E and A vowel sounds, then W sounds, then M sounds. What is the feeling you get when you read them aloud? Well, it reminds me of watching a great running back dance his way through the defensive line into the secondary. I’m a big fan of Ohio State Buckeye Brandon Saine. Watch him weave his way around defenders…isn’t that how the poem feels when it’s on your lips and tongue?

The comparison also applies to a basketball player spinning an ankle-breaking path through the opposition:

And whether or not you’re into rap, writers in that genre are often really good at manipulating the syllables in their work in a similarly pleasing manner:

And how could I overlook that Ms. Wong borrowed a line about creative borrowing?

…If the line

looks familiar, consider Chanel, who said,

“Creativity is the act of concealing

your sources.”

What Should We Steal?

- Capitalize upon your other passions or areas of expertise. So you’re a brony. Okay. You’re probably not hurting anyone, so I say go for it. What can your status as a card-carrying brony lend to your writing?

- Arrange the sounds in your poem in such a way that the language can dance. Creating alliteration in one line is a tricky and rewarding feat. Tying a number of similar lines together may be more difficult, but adds a powerful momentum and beauty to a poem.

- Follow the advice of Coco Chanel. To what extent can any creative work be original?

Poem

2014, Making Use of Our Interests, Ohio State, Shelley Wong