There’s a narrative that dictates how one is supposed to feel after a terrible event occurs. When a family member or acquaintance dies in a car accident, most people feel and act the same way. As Claudius said of the reaction to his brother’s death:

…it us befitted

To bear our hearts in grief and our whole kingdom

To be contracted in one brow of woe

The reality is that everyone is different and will respond to trauma differently. In her Prime Number essay, “The Lightness of Absence,” Vanessa Blakeslee tells the story of her reaction to the very sad murder of her cousin and describes how her feelings about the matter evolved.

Ms. Blakeslee introduces the death in the first line, taking advantage of the inherent power in such an extreme condition: “When I was twenty, my cousin Cara was murdered by her ex-boyfriend. We were both attending college in Florida at the time.” All of Ms. Blakeslee’s readers are surely as human as she is, so the release of this exposition earns instant emotion from the reader.

Much more interesting is the way Ms. Blakeslee deals with an emotionally loaded issue in a very calm and methodical manner. If you haven’t read the piece, do so now, as I’m going to discuss the ending. (I even linked it twice.)

Ms. Blakeslee certainly mourns the senseless loss of her “childhood best friend,” but she doesn’t give us a standard grief narrative. Instead, the author confronts a much more unanticipated question and one that invites thought from the reader: “What do you call it when even the weight of loss has disappeared?”

Ms. Blakeslee had a little bit of a problem. How do you create tension and keep people reading when that “weight of loss,” those emotions that were much stronger years ago, are currently absent? The solution is simple: you turn the absence of emotion into the story.

On one hand, I think I would love if the piece were a little bit longer, if we had more of a discussion of the dilemma posed by the end of the piece. Then again, ending the piece with a dilemma forces the reader to go through their own discomfort with respect to the issue.

- There are certain events and conditions that don’t evoke as much emotion in me as they might. Is there something wrong with me?

- Do people say and do things that makes me treat them differently? Is this wrong? When is it wrong?

- How long should I grieve for those I’ve lost and the bad things that have happened to people I love? What does it mean to “get over” a misfortune?

Further, the ending of the piece is appropriate to its length. At 1600 words, Ms. Blakeslee had to avoid some of the more complicated possibilities for the material. So what could be more appropriate than ending the piece with an ethical quandary?

Creative Nonfiction

Prime Number, Vanessa Blakeslee

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Katherine Riegel is a friendly woman and a good teacher. She’s also a co-editor at Sweet: A Literary Confection. Most of all, however, Ms. Riegel is a writer who loves creating poetry and creative nonfiction.

In November of 2014, Ms. Riegel published a powerful piece of creative nonfiction at Brevity. Go ahead; check out “Run Towards Each Other.” Then come back here and see why the author did what she did.

1) You begin “Run Towards Each Other” with the following two sentences:

“It is Thanksgiving, again. My smile is a weapon cutting off access to my grief-treasure.”

So…”grief-treasure” isn’t a real word. I even copied it into Microsoft Word to make sure. Then I looked on dictionary.com. Then I realized you must have made it up for some reason.

How did you decide to combine those two specific words? Why did you include the hyphen?

KR: Such an interesting question! I deliberately wanted to link those words in order to make sure the metaphor was clear. I imagined the smile/weapon protecting treasure—something precious, something coveted, something collected over time. So a stranger might see only the weapon, the defense—the smile. But the treasure being protected is actually grief. So it was layers of metaphor: smile=weapon, grief=treasure. In asking the reader to engage with complex metaphor, I didn’t want language itself to make understanding any more difficult. So I…bent language to make it do what I wanted. And I think the comparison of grief to treasure in particular is so unexpected, so out of the norm in terms of the ways we usually talk about grief, that I didn’t want the reader to be able to interpret it any other way.

2) The third paragraph is all one sentence. And there are en-dashes that split the sentence into three sections in addition to commas and everything else that makes up a sentence.

Why did you decide to combine all of those clauses? How did you make sure that the reader would know what you meant to say? What was the effect you hoped to create?

KR: Microsoft Word wasn’t happy with that sentence. (Though actually the 3rd paragraph is 2 two sentences, which itself is problematic because the 2nd “sentence” is technically two fragments separated by a dash.) In the first sentence of that paragraph, the dashes did what dashes are generally supposed to do, in that, if you took out the material inside the dash, the grammatical structure of the sentence, and its essential meaning, would be unaffected. Oh, and incidentally those were em dashes in my document; I think the formatting of the site turned them into en dashes. I wanted to put some description of my own smile into the piece, but I knew if I didn’t limit it that I could go on and on in the most unflattering ways about my own smile. This made it essential to keep the image short, tucked within a sentence. I also deliberately left out the “and” before “my new loves” because I wanted the three items in the list to be equal. Somehow adding “and” would make it feel like the last one, the “new loves,” was either more or less important than the other two. I intended the order to be more chronological than by importance.

I think also that this particular paragraph, reflecting my (the narrator’s) self after my mother’s death, is particularly fragmented. All the clauses, as you say, are both linked and separate, connected only tenuously through punctuation. The speaker, too, is just barely held together, and still doesn’t quite believe how or why she is. As for the 2nd sentence, where I get to write “me—me,” I confess I gave myself permission to do that because of some lines/line breaks in a Sharon Olds poem. It’s called “His Stillness” and the sentence reads like this:

At the

end of his life his life began

to wake in me.

She deliberately ended a line with a throwaway word—“the”—in order to get a line which begins with “end,” ends with “began,” and has “his life” repeated in the middle. I wasn’t breaking my mini-essay into lines (though I did when I first wrote it—shhh, don’t tell) but there was something really important about repeating that word “me.” The narrator doesn’t feel worthy of the support she’s gotten, so she must repeated the word “me” to persuade herself she matters, even as that words is followed by “insignificant.”

3) So, “toward” and “towards” are interchangeable, but “towards” has that extra Zzzzzzzzzzzz sound at the end. “Toward” has a nice, crisp consonanty ending.

Why did you use “towards?”

KR: I have to confess this may be just dialect. I grew up in Illinois with parents from DC and Pennsylvania who went to school in Vermont. When I take “accent quizzes,” it nearly always gets my accent wrong because of that. (I say “ca-ra-mel,” for example, not “car-mel.”) I guess, when I think about it, “towards” sounds more together-y to me. People are running towards each other—everyone is doing the action. A person would run toward a house, because the house wouldn’t be doing the action. Or maybe I’m completely full of it, and I’m a teacher, so I can come up with an answer even if I have to make it up. 🙂

4) I’m pretty sure Grammar Girl would tell you that you didn’t need that comma in the sentence, “It is Thanksgiving, again.”

How come you put that comma there?

RM: Oh, yes. Very important, and very deliberate. I wanted to emphasize “again.” It is inevitable, it keeps coming around even when you don’t want it to. Putting the comma there was to try to show the dread, to make the reader feel just how much the narrator didn’t want it to be Thanksgiving—again. Oh boy. Here we go.

5) And here’s the penultimate sentence:

“In the barn I will pull carrots out of my pockets and hold them flat on my palms.”

“In the barn” is a dependent clause that begins a sentence. All of those nerds who complain about grammar stuff might say that you shoulda put a comma after “In the barn.”What made you leave the comma out?

KR: Really interesting punctuation questions! I think language has a music to it, a rhythm. Grammar and punctuation rules are in place to help with clarity, but we all know many of them are arbitrary and some are based on the rules of Latin, which early English grammarians decided was the only “proper” language and so must be imitated. In this case, it’s clear what’s happening, and I heard the sentence in a particular way in my head. It wasn’t interrupted by a pause after “barn.” I’m one of those people who hears a voice very clearly in my head when I read; I don’t read my work aloud much during revision because it’s redundant. I heard this sentence as a whole, the image words like fence posts, regularly spaced: barn, carrots, pockets, flat, palms.

It’s odd to see how often I bend/break grammar and punctuation rules, when I emphasize clarity in both those areas as a teacher. I suppose I’m more concerned with syntax and its possibilities than with absolute rules. I want writing to be precise, in order to get across nuance and subtlety. That kind of precision requires a writer to make considered choices that sometimes break rules.

Katherine Riegel is the author of two books of poetry, What the Mouth Was Made For and Castaway. Her poems and essays have appeared in journals including Brevity, Crazyhorse, and The Rumpus. She is co-founder and poetry editor of Sweet: A Literary Confection, and teaches at the University of South Florida. Visit her at www.katherineriegel.com.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Brevity, Katherine Riegel, Sweet: A Literary Confection, Why'd You Do That?

Friends, the past few days have seen gallons of digital ink spilled over a controversy arising from Lena Dunham’s recent memoir, Not That Kind of Girl. The book is a set of essays in which Ms. Dunham discusses her life and her philosophies and was highly anticipated by fans of her HBO program Girls. Perhaps no one was more excited for the book than Random House, who paid Ms. Dunham a $3.7 million advance for the book. (Rob Spillman wrote a very interesting article about the advance for Salon.)

The controversy began a month after the book’s release when Kevin D. Williamson published a scathing piece in the National Review in which he quoted passages from Not That Kind of Girl that could easily be considered descriptions of child sexual abuse. Truth Revolt followed suit, quoting the same passages from the book; Ms. Dunham’s attorneys have threatened to sue the site.

I must begin this discussion by pointing out that I have taken great pains to maintain Great Writers Steal’s neutrality when it comes to politics and other controversial issues. I certainly have my own opinions that are hewn, I like to think, by my open-mindedness and dedication to reason and free discourse. You may think whatever you like about Ms. Dunham and Girls and her place in popular culture. GWS is a place where we discuss writing craft-related dilemmas; I am slowly working my way to making my argument that the Not That Kind of Girl kerfluffle raises a number of important issues with respect to creative nonfiction:

- When are we oversharing?

- How do we navigate tone when discussing sensitive situations?

- What reaction should we expect when we confess?

- What should we do when we get an unanticipated reaction to our work?

- Perhaps most importantly: when are we being too honest?

We certainly can’t discuss the current Lena Dunham situation without taking a look at the extracts in question, can we?

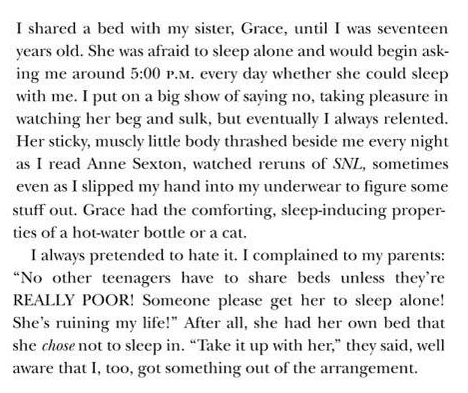

Ms. Dunham seems to describe engaging in self-pleasure during her teenage years while her pre-teen sister was sleeping beside her:

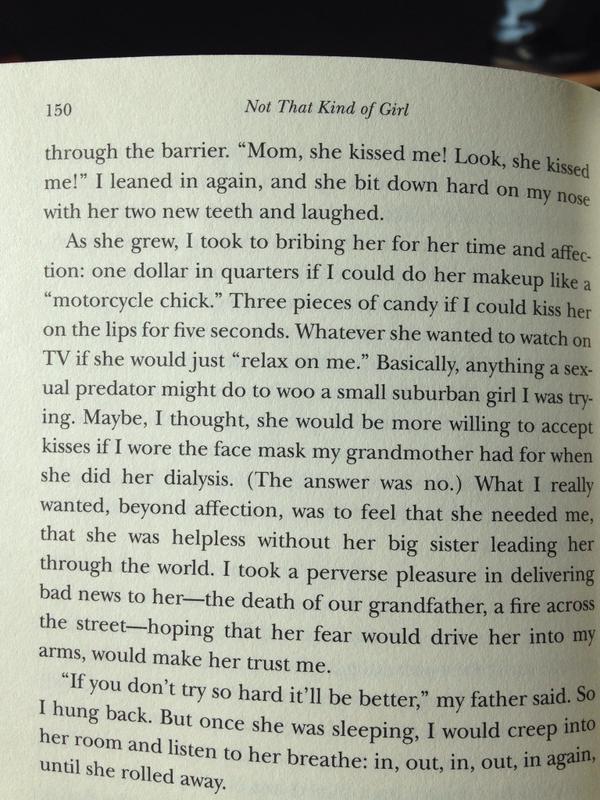

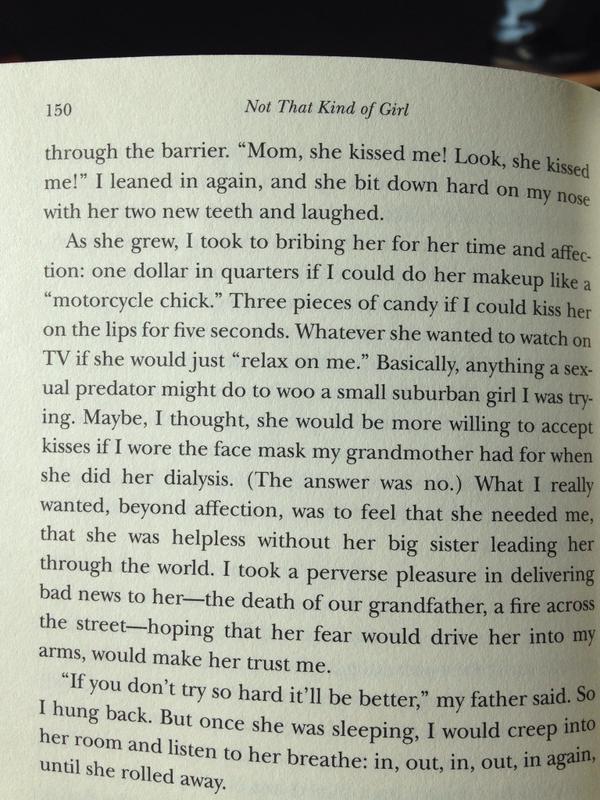

Ms. Dunham describes bribing her younger sister with candy in exchange for kisses on the lips:

Ms. Dunham describes bribing her younger sister with candy in exchange for kisses on the lips:

Perhaps most quoted was the passage in which Ms. Dunham describes an incident that occurred when she was seven:

With that bit of business out of the way, let’s devote some thought to the goals Ms. Dunham had in mind when committing these paragraphs to paper:

With that bit of business out of the way, let’s devote some thought to the goals Ms. Dunham had in mind when committing these paragraphs to paper:

- She was, no doubt, attempting to be honest with her audience. Her career seems to have been predicated on brutal honesty and openness, both physical and emotional. Not That Kind of Girl simply could not have been filled with cookie recipes.

- She was likely attempting to make further statement with regard to the female body and sexuality and societal perception of “normal” child development.

- Let’s face it: she was making sure that the book contained some titillating confessions. Ms. Dunham, like any other author, wanted her book to make a splash. I don’t think it’s fair to say that Ms. Dunham was expecting the level of pushback she received, but you can’t blame a writer for trying to gin up a bit of an argument around Pub Day.

A creative work, of course, must be evaluated on the basis of the creator’s goals. By those measures, Ms. Dunham was clearly quite successful. Perhaps too successful…

So did Ms. Dunham overshare? Ms. Dunham is part of the Millennial generation, a sea of people who have grown up in a world largely devoid of secrets. Many folks post EVERYTHING somewhere on the Internet: where they are getting their pizza, how little they like how they look in their mug shot, how funny the Wal-Mart shopper beside them is dressed.

It’s an interesting dilemma. Where is the line between honesty and oversharing? And how does that line compare when transplanted to the realm of creative nonfiction? Mary Karr is incredibly forthright when describing incidents that don’t exactly reflect her best self. Augusten Burroughs caught a lawsuit after publishing Running With Scissors; some of the other “characters” the book felt they were characterized as a “mentally unstable cult.” James Frey described his extreme and unbelievable behavior during…oh, nevermind.

Writers of creative nonfiction can’t stop writing about unsavory situations, sexual or otherwise. Not only do people love that material, but the events in question are deeply personal and don’t happen to everyone. Creative nonfictioneers must keep describing what sets their lives apart from those of others, even when the descriptions may make a reader uncomfortable.

On the other hand, these passages from Ms. Dunham’s book are pretty hardcore and relate to child sexuality…not exactly the world’s safest or most enjoyable topic. Would Ms. Dunham have lost some “honesty points” in her own mind had she struck those passages? How much does it matter that the author didn’t believe that these excerpts described, in the opinion of many, a pattern of sexual and psychological abuse?

Perhaps Ms. Dunham is embroiled in the controversy because she employed a joking and perhaps less-than-reverent tone in her piece. Now, I’m certainly not one to order a writer around; nor do I wish to order a colleague around. Perhaps the sentence “Basically, anything a sexual predator might do to woo a small suburban girl I was trying” was one step over the line. Instead of treating the subject with an appropriate seriousness, Ms. Dunham could come off as flippant to some.

If nothing else, Ms. Dunham has unintentionally started a dialogue that should not end with this little essay. What do you think? There is no absolute guideline with respect to what a writer must or should share, but where do you think the line should be painted?

Creative Nonfiction

GWS Essay, Lena Dunham, Roxane Gay

Title of Work and its Form: “Coming to the Table,” creative nonfiction

Author: Allegra Hyde

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece made its debut in Flyway: Journal of Writing & Environment. You can find the piece here.

Bonuses: Try not to be jealous; here‘s a short piece Ms. Hyde placed in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. Here is a brief interview Ms. Hyde gave to introduce herself as an editor for Hayden’s Ferry Review. Here is a short story she published in Superstition Review.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Beginnings

Discussion:

Ms. Hyde describes what must have been a fascinating time in her life. She was a first-year teacher in Eleuthera, “a skinny Bahamian out-island that dangles like a fishhook towards the Caribbean.” And she didn’t know how to cook. Her students at The Island School were very privileged, indded. Not only were they matriculating in what must be a breathtakingly beautiful place, but they were children of parents with means. One day, she and her students decide to cook a community meal sourced entirely from Eleutheran food. There were a couple hitches along the way-not the least of which was Ms. Hyde’s lack of confidence in her cooking ability-but students and staff alike enjoyed cassava-banana bread, fruit salad and pumpkin soup that contained just a hint of coconut.

I am sad to admit that I did not know about Eleuthera before reading the piece. I am well aware of where The Bahamas are located, but I hadn’t realized to which island Ms. Hyde was referring. Here’s the map extract from Wikipedia to orient us:

I think it’s pretty clear that Ms. Hyde’s first movement in the piece is an extremely important one. What’s her entry point into the story? A brief paragraph set apart from the rest of the narrative by

I think it’s pretty clear that Ms. Hyde’s first movement in the piece is an extremely important one. What’s her entry point into the story? A brief paragraph set apart from the rest of the narrative by

double spaces:

This is the situation: I am a first year teacher. I am a first year teacher at a remote environmental leadership school on the southern tip of Eleuthera, a skinny Bahamian out-island that dangles like a fishhook towards the Caribbean. I do not know how to cook.

What does Ms. Hyde gain by opening her story thus? She could easily have started off with a variation of her second paragraph:

Arriving at The Island School in 2010, I knew there would be challenges. Sunburns. The occasional jellyfish sting. Dormitory duty. But this all seemed like background noise given the opportunity I had to help students re-examine their relationship with the environment, to use the school’s own operations – which showcased methods of green living from solar hot water to biodiesel vans – as a model for inspiring a more sustainable future.

So why begin with that example of extreme narrative intrusion?

- It’s a great icebreaker and introduction. Ms. Hyde is not yet a big-time author whose accomplishments are known to the vast majority of readers. (This state could easily change, of course!) This first paragraph tells us all we need to know about Ms. Hyde to enjoy the story and does so very efficiently.

- The first paragraph is very inviting; the diction makes us feel as though Ms. Hyde is standing before us at a cocktail party, telling us an interesting and heartwarming tale.

- The complication is introduced immediately: the author claims she can’t cook…this is a story about how she took on the responsibility of coordinating and cooking a big meal.

- The setting is introduced very quickly and we’re transported to a place we’ve likely never been.

So why not begin in such a manner? Ms. Hyde seems to enjoy these “buttons,” these interjections that are given their own paragraphs. She employs the technique a few times through the course of the piece, including:

- “I never guessed that my culinary limitations would be a hurdle. I was a teacher, not a chef.”

- “It was against this backdrop that the campaign for One Local Meal began.”

While many of these interjections could simply be appended to the paragraphs that precede them, Ms. Hyde amps up the humor and reinforces the strength of her thought in these places. Most of all, it’s important to remember that we have a narrator for a reason. (Even when we’re writing about ourselves in the first person.) It’s the narrator’s job to keep the story humming and to contrive sentences in words in such a manner that we pay attention and understand.

I must say that I found one of Ms. Hyde’s choices very interesting. Her students themselves are not named or described outside of simple markers: “a glossy-haired girl.” When the author introduces local farmers and experts in Eleutheran flora, she gives them names and backstories. Now, Ms. Hyde could simply be protecting the identities of her students. That would be just fine by me. But I like to think that these choices help the reader understand what and who are most important; sure, the students are learning and enjoying a great meal. The “lower-class” characters, however, are much more interesting in the context of this piece. I loved meeting Monica Miller, a local farmer and Elidieu Joseph, an immigrant stonemason who knows best how to put wild Eleutheran plants on the plate.

The point is that we need to understand that we can’t inject every bit of knowledge we would like about the world we’re creating. Instead, we must tell the reader what they need to know in order to enjoy the greatest emotional impact.

What Should We Steal?

- Empower your narrator to do its job. It can be hard to decide where to begin a piece and where to put our sentences so that they have maximum effect…but that’s why you have a narrator.

- Offer more and deeper descriptions of the characters who are most important to the narrative. I’m finishing up a Young Adult novel (hopefully). I can’t devote pages of backstory to EVERY character…I need to tell the reader what they need to know about each of my creations.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Allegra Hyde, Beginnings, Eleuthera, Flyway: Journal of Writing & Environment

Title of Work and its Form: “Never Write From a Place of Despair,” creative nonfiction

Author: Erika Anderson (on Twitter @ErikaOnFire)

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece debuted in Issue 1 of Midnight Breakfast. You can find the work here.

Bonuses: Ms. Anderson is very kind; she offers a collection of her publications at her web site. I particularly enjoy her brief “workshop” of the author photo.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Momentum

Discussion:

This work of creative nonfiction describes Ms. Anderson’s reaction to the aftermath of her divorce. It seems clear that Ms. Anderson was figuring things out at the time and that the piece is an instance in which the author is giving the reader advice that she is also trying to internalize. There are many “rules” in the piece, several “do not”s and “never”s and the final paragraph leaves us with a sense that catharsis is on its way, albeit slowly.

I was first struck by the momentum in the piece. Ms. Anderson grabs you by the lapel and won’t let you go. How does she make this happen? Well, repetition for one thing. A composer uses motifs, short melodic passages, to bring unity and momentum to a piece. Plenty of examples can be found in the best music ever composed:

Ms. Anderson establishes the “never write” motif in her title and employs it in the piece. She eventually brings in “do not,” just as Beethoven cleverly introduces the famous “Ode to Joy” melody to the symphony before he allows it to take over the work and reach full flower.

Ms. Anderson does another thing to build and maintain momentum: she varies the lengths of her paragraphs, just as Beethoven varied the tempi in the movements of the Ninth.

I also admire the manner in which Ms. Anderson confronts one of the big problems inherent in the composition of creative nonfiction: YOU HAVE TO BE HONEST AND SOMETIMES REVEAL SOME OF THE FAILURES OF YOUR LIFE OR THINGS THAT ARE A BIT EMBARRASSING.

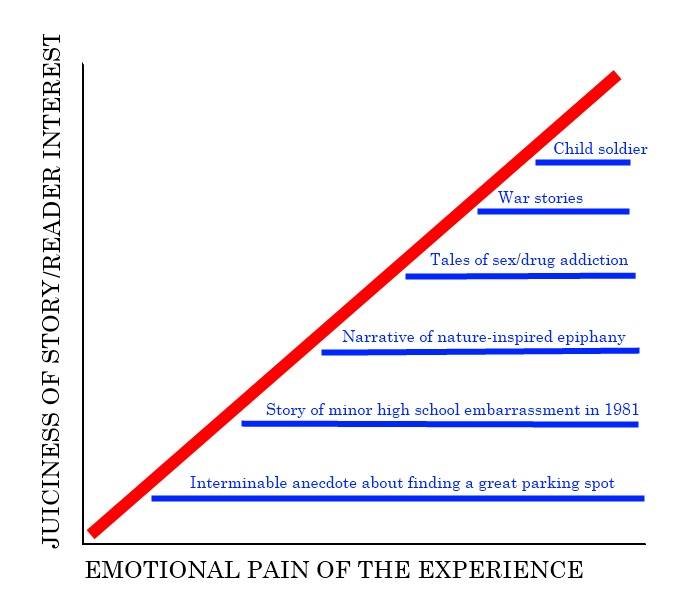

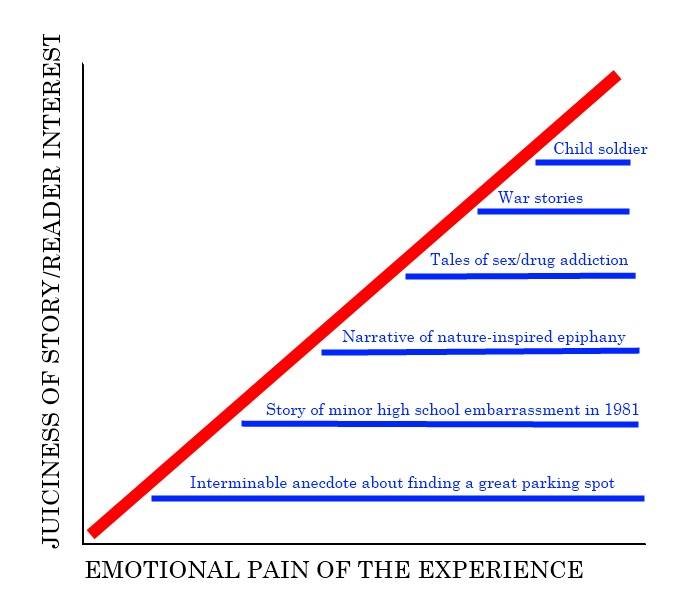

Sad but true: our lives don’t always unfurl according to our plans. We will sometimes fail in our efforts and our relationships. Unfortunately, these are the kinds of truths that we must confess in creative nonfiction. Happy stories are often meaningless or boring. Divorces? They’re usually as painful as they are “juicy.” Think about it this way. Let’s say you’re on a bus and I plop down in the seat beside you and say, “Boy, do I have a story for you. This one time, I stubbed my toe so bad that it swelled up and looked like a grape for a MONTH.” And then I keep talking about it for an hour. You’d go crazy, right?

Now let’s say that Valentino Achak Deng sits beside you and somehow organically mentions that he’s one of the Lost Boys of Sudan. I’m going to bet that you would be interested in hearing his story, even though that story is ridiculously sad and should never, ever happen in reality.

I think my ultimate point is that we NEED to confess and to bare ourselves in order to create powerful works of creative nonfiction. There may certainly be exceptions, but we spend our lives surrounded by people who hide behind projections of how they want to be seen by others. Writers such as Mary Karr are brave enough to expose their flaws. Not only are her stories more interesting than most, but they’re also more powerful.

Here are my thoughts in chart form:

Ms. Anderson’s story definitely doesn’t fall on the bottom of the red line. You don’t have to be Harold Bloom to pick up on the fact that Ms. Anderson is telling us that she was in that “place of despair.” She reveals that she may not have known her ex-husband as well as she thought. She’s brave enough to confess that she was adrift in her thirties…not the best situation, for sure.

Ms. Anderson’s story definitely doesn’t fall on the bottom of the red line. You don’t have to be Harold Bloom to pick up on the fact that Ms. Anderson is telling us that she was in that “place of despair.” She reveals that she may not have known her ex-husband as well as she thought. She’s brave enough to confess that she was adrift in her thirties…not the best situation, for sure.

It seemed to me that Ms. Anderson was being very honest with the reader, but was also employing a technique that allowed her to be frank with us. She gains distance from us through her use of point of view and choices of words. For example, here’s a passage from the piece:

You thought your husband never loved you because he could never touch you the right way. He hated that there was a right way — he wanted to pet you like a puppy, to paw at your blonde-haired forearm, to stroke the heft of your thigh, for that to be good enough. But it wasn’t, and that broke him and it broke you.

We have been told the story is nonfiction, so we assume it to be true. Ms. Anderson, however, employs the second person point of view. Why not use first person? She’s writing her own story, after all! Well, the second person allows the writer to push the reader away a little bit. We can “trick” ourselves into believing that we’re not really confessing our own problems…we’re writing about the reader’s life, right? See? It says, “You!” That means the reader! Compare the above passage after a transformation into first person:

I thought my husband never loved me because he could never touch me the right way. He hated that there was a right way — he wanted to pet me like a puppy, to paw at my blonde-haired forearm, to stroke the heft of my thigh, for that to be good enough. But it wasn’t, and that broke him and it broke me.

The sentences read differently, don’t they? The second person offers a layer of psychological protection and it also subtly turns the reader away from thinking that you might simply be complaining or laying down a list of grievances. (Not that I think Ms. Anderson is doing those things, of course.) Instead, Ms. Anderson subconsciously forces the reader to immerse him or herself in her experience. There’s no PROPER point of view for creative nonfiction (or any piece), but the point is to create the conditions under which you can tell the most faithful version of your story. If you need to switch POV, so be it.

What Should We Steal?

- Employ motifs and changes of pace to maintain narrative momentum. A speaker uses the inflection of his or her voice to keep people interested. The same principles apply to writing…just in different ways.

- Accept the fact that writing great creative nonfiction may require you to tell people your dark secrets. Everyone has a walked-out-of-the-bathroom-with-toilet-paper-stuck-on-shoe-on-a-first-date story. You may have to plumb a little deeper if you want to tell a story that will capture your reader.

- Make any changes you need to ensure you put down an honest and powerful version of your true story. I wrote a brief CNF story about something sad that happened to me when I was a kid. I simply told the true story in the form of a pulp detective short story. On the off chance it ever gets published, perhaps I’ll explain my reasoning.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Beethoven, Erika Anderson, Midnight Breakfast, Narrative Momentum

Dear reader, teaching is often as frustrated as it is rewarding. A teacher cannot force students to care or to learn or to grow…that desire must come from within. Well, Peter Melnick is a former student of mine, and a fascinating young man who has that internal desire. The gentleman was kind enough to think of me in the rush of excitement he felt after a brush with his writing idol. I suggested that he might want to share his thoughts and inspiration with all of you by writing an essay about the experience. It is just our luck; he agreed to write an essay for all of us and Great Writers Steal is quite pleased to present it. Mr. Melnick also happens to be a graphic designer and has been kind enough to produce an attractive PDF of the piece that you can read and download.

The Tough Shit I Learned from Kevin Smith

Peter Melnick

I’m pretty sure that if I never discovered the work of Kevin Smith, I would not have taken the path I had in life to become an artist as both a writer and graphic designer.

Bold statement, isn’t it? While that may be the case, it is most certainly true. Back in 2001, Jay & Silent Bob Strike Back hit the theaters. Around the time this movie was coming out, I was a 12 year old about to enter the 7th grade. Unfortunately due to having a parent who didn’t want to take me to an R-rated film (understandable), I wouldn’t be able to see the film until a few months later on VHS. Before that would happen, I was able to get my hands on a copy of the film’s script and somehow convinced my 7th grade “Reading” teacher to let me take the script and do a book report on it. My school had both an English teacher for that grade and a “Reading” teacher – the difference between the two classes? I couldn’t tell you even if I tried. Thankfully the script was released as a physical book from Miramax and I didn’t have to take 90 something pieces of stapled printer paper and use that. I probably got a good grade on it. It’s been almost 13 years since I was in middle school, so I couldn’t tell you every single grade I got back then. All I know is that not long after reading the script and then watching the movie, that exposure made me into a fan of Kevin and his work.

When you’re a kid and you discover things like films, television shows, etc., you sort of become obsessed. Deny it all you want, but it’s true. When I was 5 years old, I was completely obsessed with the Power Rangers. Three years later? Star Wars was the love of my life. A year later? Pokemon. I think you get the point. Once you discover something you like, you want to do whatever you can to learn more and enjoy what you love. Discovering the work of Kevin Smith was no different. Once I finally saw Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, I had to see everything he had committed to celluloid. By the time I reached 8th grade, I practically wore out my VHS copies of the Clerks animated series and Mallrats.

Fast forward to Fall 2007. My grades were in the toilet from high school, but I decided to enroll at my local community college to try and boost them. Sitting in the registrar’s office, I wasn’t sure exactly what I wanted to do. I didn’t want to choose Liberal Arts as a major mainly due to the fact that math and I are just not compatible. So right then and there while looking at the options I had available, I decided to go with Graphic Design as a major. Now what does this have to do with Kevin Smith? Numerous times throughout his career, he has told people to “do what you enjoy,” so I did just that. I had really enjoyed working with Photoshop over the years prior, so I thought why not?

Now we move ahead two years and I graduated from that community college with an Associates Degree in Graphic Design. At this time, I had gotten accepted by SUNY Oneonta, but due to circumstances beyond my control, I was not able to attend. For the next year, I decided to continue my education (i.e. avoid the real world for another year) and go into Communications since there were no other programs that interested me quite like that one. Again, I went with Kevin’s logic of “do what you enjoy.”

During this time, I was reapplying to some of the schools to which I applied to a year earlier. One of the schools that caught my eye was SUNY Oswego. My best friend had been attending for the past year and told me how great it was, so I decided to go for it. During that first semester, I took two Creative Writing courses, one with Leigh Wilson and the other with Chris Motto. Both were phenomenal professors and made me realize that writing was something else that I enjoyed on top of my work in Graphic Design.

The next semester rolled around and I was in a meeting with my advisor. During said meeting, she made the suggestion that perhaps I could add a minor to my college career. Looking through my options, I decided that maybe Creative Writing was the right thing for me. Over the years of watching Kevin’s work, I realized that what he was doing was essentially getting out how he felt about the world around him, expressed his thoughts through written word. This led to myself taking a poetry class the year prior at my previous college. Much like Kevin, I was writing out how I felt about the world around me. Though these were short bursts of expression, I knew that if I could bring out those thoughts in small doses, I could certainly do it in larger ones as well.

As the semester was ending, it was time to start scheduling what was to come in the Fall. The thing that I was gung ho on was taking a screen writing course. Unfortunately, I was not able to get into any of the classes. Instead, I decided to go another route: playwriting. Since both were similar in many ways (and different in others, obviously), I decided to go that route. As luck would have it, an introductory course on the subject was open for the Fall semester and was being taught by Kenneth Nichols. The only downside to the class was the 8 AM start time. Regardless, I went in and I appreciated what was being taught to me. Nichols’s teaching method was unique in that he didn’t rely strictly on showing the standard playwriting materials like the work of the greats in the field, but rather often presented clips from sitcoms, films, and even news programs. By using these sources, he showed us ways to borrow methods from other forms of media and incorporate it into our playwriting. Additionally, he showed us that it doesn’t matter where inspiration comes from. As long as something connects with you, you’ll be set. Kevin would even go on to do something similar when he worked on his soon-to-be released film, Tusk. He found a bizarre ad online and creativity was brought forth.

It wasn’t until a full year later that I would be able to take the followup course. When I did, I fell further in love with the concept of playwriting. One of the most important things that Brad Korbesmeyer gave us was the ability to have our plays read aloud and even acted out in class. Doing so, we were able to see just how things work and how they don’t. It’s one thing to think over the lines in your head, but it’s another to actually see the words and actions on your page come to life. When a play is going into production, you can’t really fix things up during a live reading. The people who are putting on the production usually like the play the way it is and may not want to see changes. With Brad’s method of having the class act out the play, you still have time for revisions for your upcoming drafts. On top of all of that, you can also get to cringe when one of your lines doesn’t sound the way you want it to (though that’s not really a positive thing to experience).

After graduating college and leaving Oswego, I returned home. One of the very first things I did was start writing again. The problem with leaving school, however, is you don’t really have deadlines. Instead, you have to create your own and go from there. Without official deadlines, sometimes it will become “oh, I’ll write tomorrow” or “I’ll write after the weekend is over.” For myself, this would go from days of not writing to weeks and finally, to months.

Over the course of the past year and a half, I have run into different people who occupy prominent places in a wide range of creative realms. Quite a few of them would be comic book writers due to my love of the medium. In many ways, the job of a comic book writer can be hard since they’re constantly on the spot to create original content on a monthly basis. Since they have such a heavy burden with issues (no pun intended) like that, I felt it would be good to get advice from them. I would hear from people like Evan Dorkin (of Milk and Cheese and Beasts of Burden fame), Justin Jordan (writer of The Strange Talent of Luther Strode), and Jill Thompson (of Scary Godmother fame). On top of all of this, I was able to hear from Bryan Johnson (the writer/director of the film Vulgar) who gave me the simple, yet valuable advice of “write every day.”

One bit of advice would come almost a year after my graduation from college. Who was it from you ask? Writer/director/producer/actor/podcaster/Bane vocal impersonator, Kevin Smith. Early in the month of May, it was announced that Kevin would be doing an “AMA” (Ask Me Anything) on the website Reddit. I knew immediately I had to ask him a question. Unfortunately, due to the large number of users, it would be impossible to get him to see my question in time, so I decided to write up my question in detail ahead of time. After all, if I’m going to ask the man something, I might as well go all the way. Ten minutes before the official thread was posted, I copied my message/question to Kevin into my phone. I then proceeded to continually refresh the app I was using like a person anxiously waiting to enter a store on Black Friday to see when the AMA was posted so I could post my question.

About 5-6 minutes before the AMA was supposed to start, I noticed that Kevin had just posted the official thread. As fast as I could, I opened up the discussion and posted my question into the box and submitted it. My question was one of the first two or three submitted, so I know that he had at least seen it. I then went over to his profile and kept refreshing to see how many answers he had given. The first one was a humorous one in which he answered back to someone who asked if they could his accountant. After that, there would not be another answer from Kevin from another several minutes. In the meantime, I noticed that my comment was getting buried at the bottom of the page with “downvotes” (Downvotes are a way to hide posts on Reddit you may not agree with or find acceptable. In this case, people were downvoting my question so their’s could be seen by Kevin over mine.), to the point that it was in the negative numbers.

This was my message that I relayed to Kevin:

“Hi Kev,

First off, I want you to know that I absolutely adore your work. It was your work that pushed me in the direction of wanting to become a writer in the first place (even going as far as adding on a Creative Writing minor to my college degree in Graphic Design). Your ability to manipulate language and so forth really inspired me and for that, I thank you. Yes, it’s cliche to say, but you are my hero.

Now, over the past few months, I’ve been doing some writing and trying to keep at it daily. There have been a number of times where I don’t know what to do next. I stare at the screen and try to figure out what to write. Others would say it’s “writer’s block,” but I’m one of those who believes such a thing does not exist.

Prior to the recent work that I’ve been doing, I would stop writing for days to even weeks. Lately though, I’ve been of the mindset where I have to push myself to write even if I don’t think it’s very good.

So, what I want to know is what keeps you going? What inspires you to write and have there been times where even you, a man who is verbally gifted didn’t know what to put to paper/type on a keyboard?”

Then it happened.

I refreshed my phone and saw the following reply to my question:

“Honestly? Death motivates me. One day it all ends for our hero, and he doesn’t get to express myself anymore. Nightmare thought for a motor mouth full of ideas (some of which are actually good). What am I waiting for? Might as well spit it all out now while I’ve got the chance.

You know what also helps? Change up the creative outlet from time to time. A writer writes, sure - but a writer can also podcast, and sometimes saying shit out loud can help. Or go take some photographs. Or shoot a short film. Or paint. Even if the words aren’t flowing, capture SOME moment that you can share or convey to others: that’s your only job as an artist. Don’t worry about whether it’s ‘good’ or ‘bad’, as art is in the eye of the beholder anyway. You just capture the moment, by any means necessary (Except, y’know, any way that hurts or kills someone else).”

After briefly shaking from the realization that the guy who made me want to become a writer actually acknowledged me, I began to calm down and to absorb the wisdom he had granted me. The idea that life ends really didn’t occur to me when it comes to writing. My lack of foresight was due, in part, to being young and believing in the “tomorrow will be another day” mentality. With that bit of advice from Kevin, it made me realize I should let whatever thoughts flow into whatever it is that I’m writing as there may not be a second, third, fourth, or even fifth chance. When the opportunity arises, you should grab it and write. Literally, if you want to take writing seriously, you should do it as though your life depends on it. Otherwise, those thoughts will never be free and be shared with the world around you. In a way, I wish I knew that bit of advice sooner for the fact that maybe I could have gotten more things out earlier than I did. To be fair, however, there’s no time like the present, so it shouldn’t matter how soon or how late I began writing. The fact I’m getting all of my thoughts out now is the most important thing.

The suggestion of taking part in as many activities as possible was also incredibly helpful. Like I had stated earlier, I’m a graphic designer and writer. I already have my hands in two pots. Why not go and do more? Be creative in as many avenues as possible. Sure, the product of one might not be as good as the others, but it doesn’t matter. You’re capturing how YOU feel. It shouldn’t matter what the quality is. Look at the work of Ed Wood. Sure, what he made wasn’t great to many, but he gave the world his vision (no matter how strange it was). There were probably some better takes from his films that made it to the cutting room floor, but what he used was what he felt was right for that situation.

Will I listen to every bit of advice that Kevin gave me? Absolutely. In many ways, it helped push me to go further as a writer. I shouldn’t look back and I shouldn’t be so critical of my own work. I’m also going to be starting up a blog of my own in the near future to jot down my thoughts about the world around me. I used to maintain a blog when I was a teenager, but eventually abandoned it. The blog isn’t the only place where my writing abilities will be showcased. For the past few months, I’ve been keeping busy working on a play that I hope to shop around to various playwriting contests within the next few months. I’m always going to be a graphic designer, first and foremost. I preoccupy my time doing freelance work for clients in a variety of realms, be it logo design, poster work, among others.

I just feel that no matter what, if you want to be serious about what you do, you should live every day like it could be your last. Be brave and take a chance. This can be in the form of the littlest things like starting a blog or painting a picture, to the large like going skydiving or bungee jumping. Kevin told me to “capture the moment” and I hope to do so not just with my art, but also with my life.

Peter Melnick is a graphic designer, writer, and graduate of the State University at Oswego. If you would like to take a glimpse into his everyday life, follow him on Twitter (http://www.twitter.com/PeterMelnick). He is not related to the composer of the same name, but was once friends with said composer on Facebook for a day.

Creative Nonfiction, Feature Film

2014, 37, Chewlies Gum, Clerks, Finger Cuffs, GWS Essay, I'm Not Even Supposed to Be Here Today, Kevin Smith

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

B.J. Hollars is a highly accomplished and very friendly writer. He has published two books of nonfiction and a collection of stories…that’s what we call range! Mr. Hollars placed an essay called “Blood Feathers” in Issue 53 of Prime Number, a very cool journal. You can read the essay here.

Once you’ve read the essay, you will be able to understand fully the intelligent way in which Mr. Hollars explains why he did what he did in the essay:

1.) The piece is filled with playful, poetic language that is often laugh-out-loud funny. I was a little surprised that you used the phrase “less-than-zest” to describe Harley’s attitude toward life. Did you use that phrase because it rhymes and sounds fun? How come you didn’t use a more conventional one-word adjective?

BJH: Generally I’m a big believer in using one word over two. Brevity, I often joke, is close to Godliness. But I think the phrase “less-than-zest” is more than mere descriptor. Yes, I probably thought it was funny, and sure, I probably liked the rhyme, but I think “less than zest” lightens the tone of the essay.

Here’s the full sentence: “This seemed far too existential a question for the indignant cockatoo, whose apparent disinterest in living rivaled Harley’s own less-than-zest for life.”

I could have written: “…whose apparent disinterest in living rivaled Harley’s suicidal tendencies.”

But I think I wanted to limit the number of times I actually used the term “suicide” (or in this case, “suicidal”). Throughout the essay, I walk a fine line between seriousness and silliness. But I hope the reader will leave the essay realizing the suicide is always serious, even when we’re talking about a parrot.

2) Each section ends with a “button,” a cool sentence that is either funny or meaningful and wraps up that bit of the narrative. How many of these happened naturally? Did you have to go back and punch up any of these buttons?

BJH: That’s kind of you to call them “cool.” A less-kind reader would likely roll her eyes and tell me to knock it off with the melodrama.

I distinctly remember a writing teacher of mine once telling me to knock it off with the buttons, that they diminish in power over time. I think that’s probably true. But I originally wrote this essay to read aloud, and the buttons function quite well in the oral format. I think they serve as signal phrases of transition for the listener, a kind of bridge that brings listeners from one section to the next. I hope that’s true of readers as well.

3) People like animals. I like animals. Your story is about a bunch of animals. When you worked at the pet store, you had to feed the birds; if the syringe was too hot, you could have burned the baby birds’ throats. Were you worried that people might have trouble liking your essay because they were worried about the animals?

BJH: You know, that was never a concern of mine. Rest assured, I’m unlikable for any number of reasons, but my ineptness with the animals wasn’t a character risk I considered. Looking back on that job at the pet store, I can honestly say I made a good-faith effort with those animals, often paying the price in blood. I’d literally come home from work some days and my fingers would look liked bloated pincushions. The hamsters were the worst—the dwarf hamsters, in particular. (Some nights I still wake up flinging dream-induced hamsters from my body).

But I think the reader gets the sense that I’m trying, that I’m giving these creatures my all, even though I likely didn’t possess the expertise required to do right by all those animals. It would be a lie to say that nobody ever died on my watch, but as I note in the essay, they were mostly fish, and the lifespans of fish are always a bit suspect.

If any of the essay’s lines redeem me, I think the redemption starts here: “One after another I’d stick the syringe down their gullets, pressing the mix into their stomachs as their bodies inflated, their bulging eyes fixed skeptically on my own. Each night they reassessed whether I was the bringer of nourishment or the angel of death…”

I tried to be the former, and only on occasion was I the latter. I think readers get that. At least I hope.

4) Your veterinarian has a beautiful and dark sense of humor. The vet informs you as to what “blood feathers” are and gives you a really powerful line: “This bird of yours, he knew what he was doing.” Did you write these things down at the time so you wouldn’t forget them? We all participate in those “Ooh, that was a good one!” moments…how can writers like me use them in the same way you did?

BJH: It’s quite likely I wrote that line down somewhere, but as is usually the case with me, I immediately lost that note. Thankfully, that moment was so dramatic (read: traumatic), that the vet’s words lingered with me.

Of course, I admit that there’s a chance I didn’t get the words out perfectly; that is, perhaps the vet said it slightly differently. At least six years had passed between the event and the first draft, so I made do with the memories that remained. But that line remained quite vividly, it’s hard to forget a line like that. I remember hearing it and thinking, This is all our fault.

5) The piece consists of parallel narratives: your experience working in a pet store is placed against your time with Harley the parrot. How’d you figure out to put the two together? Were you writing them separately and a gust of wind blew the papers together and you liked the result? Was it the plan from the beginning or did it come later on?

BJH: I wish it were as simple as a gust of wind. But in truth, when I first started this piece in 2012, I didn’t know the second half of this essay. I knew I needed to write about Harley, about my family’s experience with him, but the essay didn’t gain traction until I began thinking hard about my time at the pet store as well.

While I wouldn’t have identified this strategic strategy when I first wrote the thing, looking back, it appears as if I tried to suture the two halves of the essay together around the shared theme of good intentions. My father wanted to save that bird, and I wanted to keep my creatures alive. We were both probably a bit out of our leagues, but our intentions—we hoped—would see us through. Yes, there were victims along the way, but we too—in some small way—were victims. Our failures humbled us from trying too hard to save others, and giving up—for us—was heartbreaking.

B.J. Hollars is the author of two books of nonfiction-Thirteen Loops: Race, Violence and the Last Lynching in America and Opening the Doors: The Desegregation of the University of Alabama and the Fight for Civil Rights in Tuscaloosa—as well as a collection of stories, Sightings. His hybrid text, Dispatches from the Drownings: Reporting the Fiction of Nonfiction will be published in the fall of 2014. He is an assistant professor of creative writing at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, B.J. Hollars, Prime Number, Why'd You Do That?

Title of Work and its Form: “To Fall,” creative nonfiction

Author: Meghan McClure

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece made its debut in Volume 3, Issue 1 of Pithead Chapel. You can read the piece here.

Bonuses: Here are three poems that Ms. McClure published in Superstition Review. Ms. McClure is the Poetry Editor of A River and Sound Review; why not check out the work she has curated for us?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Unexpected Choices

Discussion:

In this piece of flash creative nonfiction, Ms. McClure recounts an experience she had when she was six. She “watched a man fall from a bridge.” Now, that’s certainly a very traumatic experience for a kid. Ms. McClure does the vital work of literature: she employs her intellect to try and find some meaning in the experience. Ms. McClure takes an interesting linguistic approach. What does it mean to “fall?” Why do we use that verb with the noun “love?” “Fall” is a relatively active verb, but the action represents an interregnum between two far more definite states. In the case of the falling man, life and death. Confusion and certainty.

If you’ve been writing for any length of time, you have heard that you should “SHOW, don’t TELL.” In general, this is great advice; the reader wants to be immersed in the story you are telling. “To Fall,” however, represents an example of how powerful “telling” can be. Even though Ms. McClure was rapt as the scene unfolded, she was six and children often don’t have Shawn Spencer-esque powers of perception. Further, her memory has changed the event over the years that stretched between the moment the man fell and the moment Ms. McClure uncapped her pen and began to write.

Ms. McClure made a number of smart choices that addressed the possible pitfalls in telling a story that is, by necessity, a fragment:

- The piece is a short short, which frees her of some obligation to specific detail. Ms. McClure didn’t know the man, didn’t know his story, so all she had was his last moment, the size of narrative that is perfectly appropriate for a 400-word piece.

- Ms. McClure didn’t make up any additional detail; the titular fall is the centerpiece of the story, but serves as a complementary element.

- “To Fall” views the event through a couple interesting intellectual lenses. Ms. McClure does an analysis of the verb “fall” and brings in a literary reference and the story of Vesna Vulović, a woman who fell 33,000 feet without a parachute and survived.

Ms. McClure, you will note, is an accomplished poet. It should come as no surprise that she made the choice to fill this short short with sentences that demonstrate a focus on language instead of narrative. Here’s the first couple lines of “To Fall:”

The stomach falls. We fall in love. We fall apart, asleep, behind, off the wagon, in line, on deaf ears, back on. We fall prey to.

If your primary focus is on narrative and your lines usually reach the right margin, you may wonder what can make prose poetic. There’s no absolute answer, of course, but read those first lines again. Now look at them after I hit “return” a few times and “tab” a few more:

The stomach falls.

We fall in love. We fall apart,

____asleep,

______behind,

________off the wagon,

__________in line,

____________on deaf ears,

_____________back on.

We fall prey to.

It looks like a poem, right? Perhaps the lesson is to understand when a section of our prose requires us to slow down and listen to sounds and to try and craft sentences that feel like poetry.

What Should We Steal?

- Tell, don’t show. I know! It feels strange to write the sentence, but our choices must serve the story we’re trying to tell or the question we are trying to confront.

- Remember that “poetry” can be a prominent element of your prose. A short short, for example, doesn’t allow you to pump out pages of exposition. Instead, we must take advantage of poetry’s ability to distill emotion in the space of strikingly few words.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Meghan McClure, Pithead Chapel, Unexpected Choices

Title of Work and its Form: “A State of Feeling,” creative nonfiction

Author: Rachel Luria

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece was published in the Spring 2013 issue of Phoebe. You can read the piece here.

Bonuses: Ms. Luria was one of the editors of Neil Gaiman and Philosophy; why not check the book out at Powell’s? Here‘s a PopMatters review of the book.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: In Medias Res

Discussion:

Ms. Luria was feeling the deep loneliness to which many of us can relate and was hoping to find companionship. So she went to Dragon*Con, a gathering of folks hoping to celebrate “all things science, science fiction, fantasy, and horror. (I haven’t been myself, but I’m guessing it could be a lot of fun.) Ms. Luria was under the impression that she would find her soul mate at the conference, saying, “If I can’t find a man at Dragon*Con, then I am definitely going to die alone.” Ms. Luria describes her experience in speed dating and how she felt when surrounded by all of the other attendees. The account is interspersed with vignettes exploring the depth of her loneliness; she went quite some time without being in a relationship and struggled with the internal and external stresses resulting from such a condition. Near the end of the piece, we learn that Ms. Luria’s loneliness was broken when she met someone online and that her day as a zombie bridesmaid represented a fairly low point in her life whose emotions never truly leave her.

Ms. Luria makes a wise choice in beginning her piece “in medias res.” (That’s Latin for “in the middle of things.”) Instead of describing how she registered for Dragon*Con or the boring and commonplace process by which she got to Dragon*Con, she begins with a scene that finds her standing outside of the conference hotel. Two young men are offering hugs; some “awkward” and other “deluxe.” Not only is her mid-scene opening a good idea because it immerses us quickly in her narrative, but also because she chose a very good anecdote. These young men are probably a lot like many video game/comic book nerds. There are certainly exceptions, but these folks are often socially awkward and aren’t often at the top of the list when women decide who they want to date. (The popular perception and the way society treats them doesn’t exactly help them in this regard, does it?)

Like the author, these young men are hoping to find a connection…possibly a romantic one. This opening anecdote primes us perfectly for the overall theme of the piece. Ms. Luria is lonely and she’s surrounded by people who are also somewhat adrift. The opening of “A State of Feeling” teaches us two important lessons in one: prose writers may wish to begin in the middle of the drama and they are also well-advised to choose anecdotes that tie strongly into the theme of the overall piece.

“A State of Feeling” has at least one thing in common with Kent Russell’s excellent “American Juggalo.” Both nonfiction pieces feature stories that are told by someone who is at once part of the group they’re analyzing while maintaining a kind of distance. Yes, Ms. Luria took place in the Dragon*Con speed dating. Yes, she talked to a guy who was dressed like Luigi. She doesn’t, however, bore us with the mundane parts of her time. Did she go see the Firefly panel? Maybe. I’ll bet she ran into an actor who has appeared on Star Trek. She didn’t tell us about these moments because they didn’t fit the tone that she took. She’s IN the Dragon*Con world, but not OF it.

Why is this a shrewd choice? Taking this stance allows her some objectivity. The distance helps her to contextualize her feelings, both about herself and those around her. Maintaining this distance can be very difficult, particularly when writing creative nonfiction. I’ve written a little bit about my somewhat challenging family situation and it’s really easy to slip into pathos when logos and ethos are a better overall fit. We care that she feels lonely, but we’re not going to understand it unless she can describe it from a writer’s perspective.

What Should We Steal?

- Begin the narrative in the middle of the story and with a thematically significant anecdote. Doing so weeds out the boring parts and gets us to care about your characters very quickly. (This is especially true if YOU are the character!)

- Describe your personal experiences as a writer, not as the individual who experienced them. Your humanity will bake the emotion into your writing all by itself; it’s your job to use your rhetorical skills to make us understand what the experience truly meant.

Creative Nonfiction

2013, Dragon*Con, in medias res, Phoebe, Rachel Luria

Title of Work and its Form: “Disconnected,” creative nonfiction

Author: Jacqueline Kirkpatrick

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece debuted in Issue 8 of Mason’s Road, a cool online journal produced by Fairfield University’s MFA in Creative Writing Program. You can read the piece here.

Bonuses: My Google search for more material from Ms. Kirkpatrick seems to indicate that she’s a frequent participant in public readings. Good on her! We should all endeavor to share our work in these venues. (Maybe I’m just thinking about myself.) Here is a brief interview Ms. Kirkpatrick gave in support of her MFA program at The College of Saint Rose. Here is one of Ms. Kirkpatrick’s poems.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Cool Conceits

Discussion:

Like many essays, this piece is split into sections; the vignettes combine to reveal a deeper truth about Ms. Kirkpatrick and her life. The author begins with blunt sadness: “At five I was abandoned on a doorstep in a trailer park just outside of Albany.” We receive further revelations, each tied to a digit from the phone number of Ms. Kirkpatrick’s childhood home. “Seven” is part of the phone number and has some significance to her; she has the number tattooed on her ankle, she was her adoptive mother’s seventh child. Nine? She has moved that many times since the age of twenty-two. In the end, of course, she puts everything together and offers some insight as to what the phone number means to her.

If you read a lot of my GWS, I think you’ll find that I often find myself focusing on the structure of a piece. In this case, Ms. Kirkpatrick has found a cool “hook” for her story: a phone number. Sure, it’s just seven digits (without the area code), but the number has a great deal of meaning. You likely remember your childhood phone number. Why? That number represents safety. If anything went wrong, those are the digits you punched into a pay phone. You may even remember a phone number from a commercial jingle. Like any other snippet of music that has been burned into our souls, we may remember the moment we first heard the song and how we were feeling.

If you watch daytime TV, you have probably seen this commercial:

It will be a while before you forget the phone number, won’t it? If you’ll recall, Tommy Tutone had a big hit in the 1980s with the Alex Call and Jim Keller song “867-5309/Jenny.”

What does the phone number really represent? Well, ask your parents if you’re not sure. I don’t want to be the one who tells you. Ms. Kirkpatrick, as I pointed out, builds her piece around the phone number. Whether or not the serendipity is contrived, it’s meaningful that each digit of that important number relates to her life in some way.

I think that structure is a particularly important element of creative nonfiction because we may or may not be describing life experiences that are very unique. Sure, the heartbreaks I’ve experienced are different from those in your past, but they boil down to a lot of the same emotions. Ms. Kirkpatrick and I seem to have…difficult childhood situations in common. (Not that I’m complaining; mine could surely have been worse.) I’ve certainly read a lot of literature about people whose childhoods had problems…I’m even hoping to finish a book about a character who is going through one. As Ms. Kirkpatrick points out with her structure, the experience alone is not what is most important; it’s how we tell the story. The author has chosen a felicitous and accessible structure that allows her to tell a big story in small sections that combine to mean more than the sum of their parts.

Why does “Disconnected” remind me a little bit of John Cheever’s “Reunion?” Well, both are about childhood, of course, but look at the similarity in the sentences each writer crafts. Both of the stories feature lines that are short and calm and declarative, even though they are packed with emotion. Compare:

“Reunion”:

We went out of the station and up a side street to a restaurant. It was still early, and the place was empty. The bartender was quarrelling with a delivery boy, and there was one very old waiter in a red coat down by the kitchen door. We sat down, and my father hailed the waiter in a loud voice.

“Disconnected”:

Seven is my favorite number. I had the number seven tattooed on my ankle. It was my seventh tattoo. I married my seventh lover. The woman who adopted me had six children—I was her seventh. I was born on July 7.

Why is this sentence structure a significant choice? Both pieces are packed with emotion already; neither author needs to do much to evoke a reaction in a reader. Longer sentences packed with more pathos would detract from the reader’s experience. We wouldn’t be experiencing a story; we would be providing free therapy. The writers of these pieces don’t want us to be their confessors. They want us to be their audience.

What Should We Steal?

- Emphasize storytelling over the story when necessary. The leanest story can be captivating if it’s told properly and the world’s most complicated story can be boring if the writer fumbles the ball.

- Allow the situation and characters to dictate the emotion in a piece, not the sentences themselves. The reader’s sympathy should be earned with strong use of craft.

Creative Nonfiction

"867-5309/Jenny", 2013, Cool Conceits, Jacqueline Kirkpatrick, Mason's Road