Title of Work and its Form: Season Four of the Television Program Arrested Development

Author: The program was created by Mitchell Hurwitz (on Twitter @MitchHurwitz). Much of the original creative team joined him, including Jim Vallely.

Date of Work: The episodes premiered on May 26, 2013.

Where the Work Can Be Found: The episodes can be found streaming on Netflix. (Thank you, Netflix!)

Bonuses: Here is The Onion A/V Club’s ongoing coverage of the program. Here is a massive chart from NPR that chronicles the running jokes in the program.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Characterization

Discussion:

Well, friends, you knew this essay was inevitable. I’ve already espoused my deep love for the first three seasons of Arrested Development and the fourth season does nothing to tarnish that legacy. As for a summary? The fourth season takes place several years after the show ended on Fox. We learn how each of the characters spent their time. George Maharris went to college and studied abroad in Spain. (He did a little bit too much studying, perhaps.) Maeby went to high school again and again. Tobias and Lindsay bought a house they couldn’t afford and traveled to India. Michael built Sudden Valley and lost everything. Lucille goes on trial for stealing the Queen Mary. George Sr. becomes a sweat lodge guru…it’s really hard to summarize what happens.

Hurwitz and friends had a massive challenge in front of them. Fans of Arrested Development had very high expectations for the new episodes. The new season had to be written in such a manner that filming would coincide with the actors’ busy schedules. There are many Bluths whose stories needed to be told in addition those of the tangential characters we all know and love. What is the main reason that Season Four succeeded? It’s the same reason that any extended narrative succeeds: the characters are deep and the characters drive the humor.

Think of just about ANY great extended narrative. Harry Potter. Lord of the Rings. Cheers. All in the Family. Seinfeld. The Dick Van Dyke Show. The situations and the humor (there IS humor in Harry Potter) emerge from the characters; it isn’t foisted upon them. Mr. Hurwitz and company, in a way, didn’t write the new season as much as they figured out what the characters would be doing. Think about DeBrie, one of the new characters. She’s an STD-ridden former actress with a heart of gold. Tobias meets her at the Method One clinic, where she’s doing one of her monologues. (Tobias is a bad actor, so it makes sense that he would confuse NA-type confessional as an actor plying her craft.)

After her character has been well-established, Tobias tries to get her back into acting by saying: “No, DeBrie, come on… Don’t you want to get back on that horse?”

To which DeBrie replies, “Even better!”

It’s not a complicated punchline, but the humor is derived from DeBrie’s constant desire to use narcotics.

Think about the extended scene in the first episode in which Michael, Maeby and George Michael are trying to decide how the voting-out procedure will go. If we didn’t know the characters, we would probably find the scene alone pretty boring. Instead, we love the scene because so much is going on and it’s derived from the characters.

- Michael doesn’t understand how pitiful he has become and that his son wants to get rid of him.

- George Michael is trying to break out of the Bluth mold and to get some independence from the family, a difficult proposition. He’s even named for his grandfather and his father. He wants to seduce Maeby (and was about to when Michael first burst in).

- Maeby wants to get FakeBlock going (if I recall correctly) and wants to make pop-pop with George Michael and probably wants to eliminate reminders of her inattentive parents.

The audience understands the emotional stakes for the characters, so they care and flinch and laugh at the same time.

Another reason that the new season is so great is that Mr. Hurwitz gave us exactly what we all wanted without giving us exactly what we wanted. It would have been very easy for him to create a less complicated version of Arrested Development in order to please the maximum number of people. Instead, Hurwitz gave us what we REALLY wanted: a work that is complicated and requires that the viewer pay attention.

Season Four will age very well because Mr. Hurwitz followed his muse in the confines of his real-world restrictions. I think I read in an interview that he could only get the whole cast together on-set for two days. The budget for the new episodes was likely lower than the budget for the Fox episodes. Therefore, Mr. Hurwitz changed the Arrested Development format in a way that he felt was true to the characters and his goals on the original show. Had he not experimented with the Rashomon structure and each-character-gets-a-short-film idea, the art would suffer. It’s no longer 2006, so he couldn’t pretend as though he were making whatever the original Season Four would have been. He created the show that was dictated to him by his muse.

One of the million things I’ve always loved about Arrested Development is how clear it is that everyone on board bought into making the show great. It’s hard to make great comedy if you are being “reverent.” Comedy is, by its nature, irreverent. (That’s why it is sometimes difficult to find good comedy by conservatives. Sorry, but it’s true. Prove me wrong?)

There are many times in Season Four in which the writers are making good-natured jokes about the actors. For example, the acclaimed director Ron Howard gets a “hat haircut” and calls all of his barbers Floyd. The design accent above his office door is a ballcap. (And Brian Grazer’s office next door is sculpted to look like Mr. Grazer’s trademark hair.) Rocky Richter sits in for his brother on Conan and makes a joke about Ron Howard’s hair. Mr. Howard could easily have had any of these details excised, but he didn’t. Why? Because he is laughing WITH the writers and the audience and because he is apparently as emotionally secure and as happy as he should be. Mr. Howard has reverence for storytelling and comedy and pleasing the audience and doesn’t revere himself in an unhealthy manner, all of which benefits the work as a whole. Isn’t this attitude one of the marks of a true artist?

What Should We Steal?

- Derive humor and drama from your deep, complicated and human characters. A story is not as compelling if the reader can see the hand of its creator. Instead, the reader should feel that he or she has been offered a window into another world and a glimpse into the lives of real people.

- Write to satisfy your muse, not your audience, imagined or real. You’re more likely to impress the audience if you impress yourself first!

- Allow yourself and your treasured characters to be the butt of the joke. Within reason, your priority should be to serve the work, not yourself.

Television Program

2013, Arrested Development, characterization, Her?

Friends, the first GWS giveaway was a success! The site is accumulating Twitter followers and Facebook likes all the time. But I want more. (Who doesn’t?) I don’t currently make any money off of the site-and likely never will-but I get great satisfaction out of being a resource for the great community of writers.

Like I said, I have no money. That’s why I picked up a bunch of awesome used books from the Oswego State library’s recent book sale. I’m giving away the following packages of books. Some books are more gently loved than others, but who doesn’t love getting library copies of books they get to keep? You can write in the books, dog-ear pages…anything you want. The words are what matter, right?

Package #1

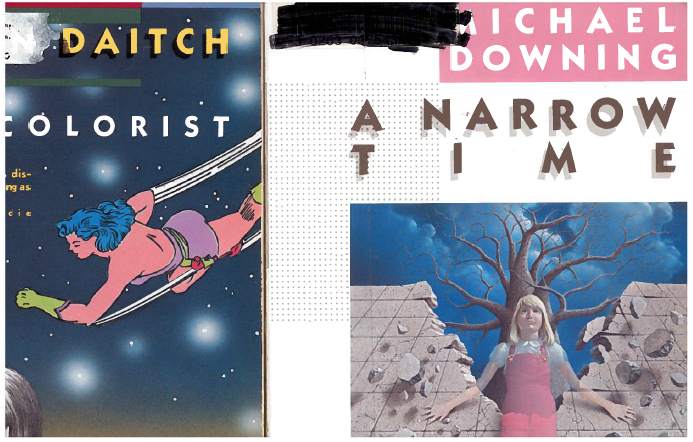

Michael Downing, A Narrow Time

Michael Downing, A Narrow Time

Susan Daitch, The Colorist

Who doesn’t love the Vintage Contemporary series?

Package #2

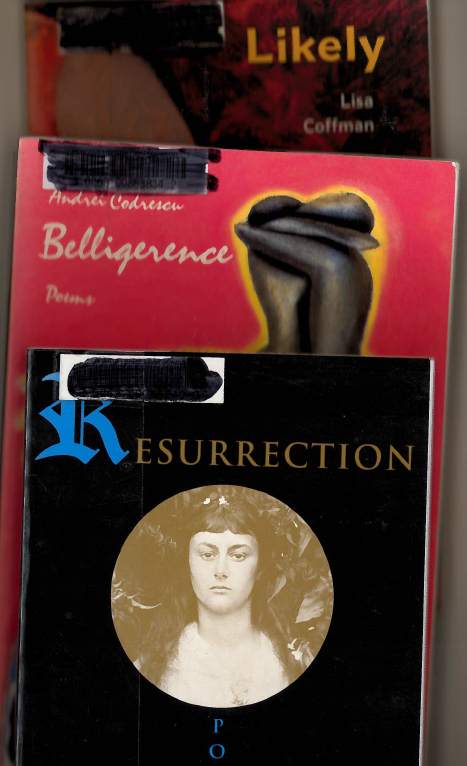

Three books of contemporary poetry:

Three books of contemporary poetry:

Nicole Cooley, Resurrection

Andrei Codrescu, Belligerence

Lisa Coffman, Likely

Package #3

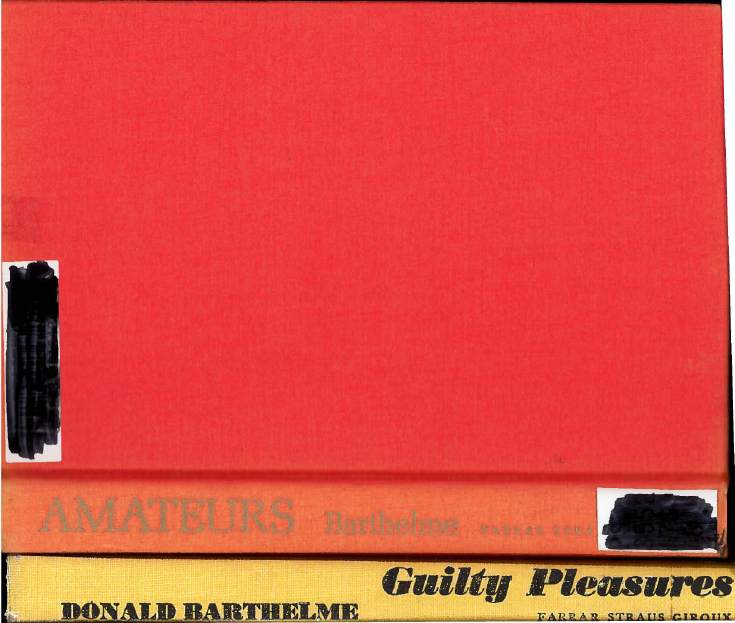

Donald Bartheleme, Amateurs

Donald Bartheleme, Amateurs

Donald Barthelme, Guilty Pleasures

Package #4

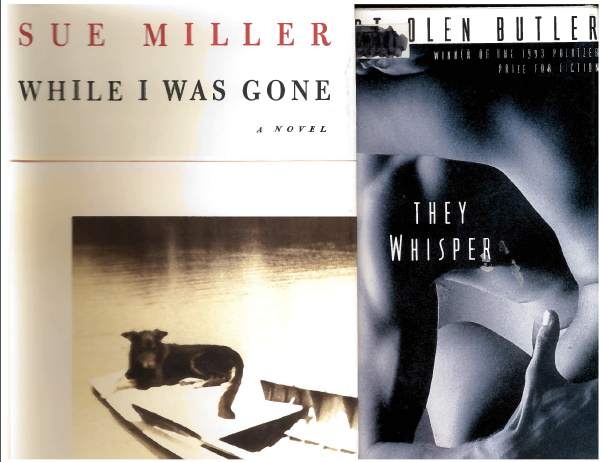

Sue Miller, While I Was Gone

Sue Miller, While I Was Gone

Robert Olen Butler, They Whisper

Two great writers at one great price! (Free.)

Package #5

Asne Seierstad, A Hundred and One Days

Asne Seierstad, A Hundred and One Days

Asar Nafisi, Reading Lolita in Tehran

How can you win the book package of your choice?

- Either “Like” Great Writers Steal on Facebook or follow Great Writers Steal on Twitter. (Or do both. That’s fine.)

- Share a Great Writers Steal essay with your friends, tweet a link, call them up on their cell phones…do something to interact with GWS in mind because a winner will be selected around the time when the site has 200 Twitter followers or 120 Facebook Likes. If new folks don’t hear about the site and don’t interact with it on social media, no one wins!

- Post some statement on the official “Second-ever GWS Giveaway! Barthelme! Robert Olen Butler! Contemporary Poetry! Vintage Contemporaries!” Facebook thread. It’s stickied at the top of the GWS Facebook Page. It doesn’t matter what you post. “Entry” or “I’m in!” or “I hope I win the books!” I don’t care, because I am going to use a random number generator to select two winners. Each winner gets to choose one of the five packages of books! See? It’s not that hard.

Giveaway rules: come on, now. I have no money and I’m doing this out of the kindness of my heart. I make the final decision and stuff. I’m just a writer and a teacher trying to get more attention for his fun (and free) effort to share storytelling techniques with the world. I can change the rules at any time.

Thanks for all of your support! It means a lot to me and makes doing GWS a lot of fun.

Uncategorized

2013, Giveaway

Title of Work and its Form: “Inquest,” poem

Author: Natalie Shapero

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem was first published by The Awl, a very cool publication that you should explore in full. You can find “Inquest” right here.

Bonuses: Here is Ms. Shapero’s page on the Poetry Foundation site. (You will find two of her poems there.) Here is a poem Ms. Shapero placed in Verse Daily. Here is a cool interview she did with Rob Stephens for HTML Giant. The interview was done in the interest of No Object, Ms. Shapero’s new collection from Saturnalia Books. If you needed additional motivation to buy the book, well, Ms. Shapero got a blurb from another of my favorite poets, Denise Duhamel.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Gymnastic Wordplay

Discussion:

This first-person poem features a narrator who speaks in stream of consciousness. Ms. Shapero has chosen to make the narrative of the poem a little abstract, so your interpretation may vary from mine. (And that’s okay!) I get the image of someone who has gone to work a little hungover or still drunk from the night before. He or she has locked themselves in the bathroom (or maybe a closet, depending on how drunk they are). The effects of the “gin-blue downpour” have a discernible climax, seen in the final line of the line of the poem. The narrator quits, heading off for (hopefully) greener shores.

What do we notice first about the poem? The beautiful use of language. Ms. Shapero’s lines are extremely fun and musical. Look at the way she uses vowel sounds in the first few lines:

Just in from a gin-blue downpour, pound

on the door like a cop knock, not

with the knuckles

See how many times she uses the same vowel sounds? (in/gin, down/pound, cop/knock/not) You’ll also notice that she often alternates the long and short sounds of the same vowel. (down/pour/pound) The narrative may be a little abstract, but Ms. Shapero makes sure to give us something very concrete on which to hang our attention. What is the emotional effect of the use of the vowel sounds in the poem? I am reminded of the floor routines done by gymnasts. With great grace, someone like Shannon Miller would unspool all kinds of flips and whatever-you-call-thems in one direction. Next, to demonstrate the control she had over her body, she would turn those movements in a different direction. Here’s an example of one of Ms. Miller’s floor routines. I am not ashamed to admit that I had a crush on her in 1996.

As you read the poem aloud—something you should always do with poetry—you’ll notice that your tongue is doing some gymnastics of its own. Understanding the narrative of the poem might take a little bit of effort, but Ms. Shapero gives us something else that is very easy to understand and enjoy.

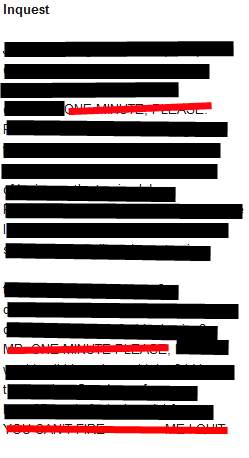

Ms. Shapero injects the poem with suspense. First, there’s the knocking on a door; when you hear that happen in your home, aren’t you compelled to answer it and find out who is there? (Perhaps there’s even the small hint of danger when you hear someone pounding on your door.) A simple glance at the poem also adds tension because Ms. Shapero has put several words in ALL CAPS.

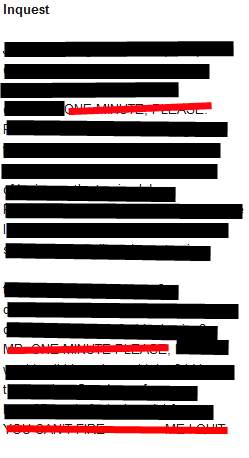

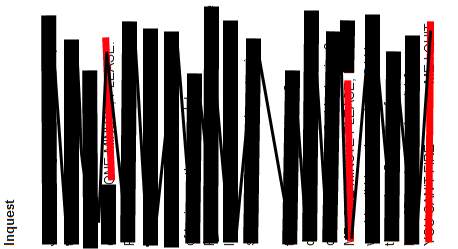

Look what I’ve done. I’ve covered all of the “standard” lines in black and the ALL-CAPS lines in red.  The ALL CAPS creeps up on your a little bit, doesn’t it? Ms. Shapero establishes that she will use the technique and then hits you with it at the end. Here’s another way of thinking of the structure:

The ALL CAPS creeps up on your a little bit, doesn’t it? Ms. Shapero establishes that she will use the technique and then hits you with it at the end. Here’s another way of thinking of the structure:

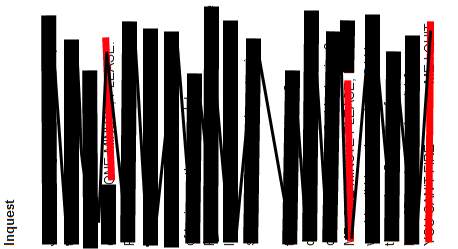

Okay, so I’m not a master with MS Paint; that much is clear. But doesn’t the poem resemble an intimidating seismograph when it looks like this? The disturbance is getting closer, isn’t it? Perhaps we don’t always think about this consciously when we flip to a new poem in a journal, but it probably has some effect on you on a subconscious level.

Okay, so I’m not a master with MS Paint; that much is clear. But doesn’t the poem resemble an intimidating seismograph when it looks like this? The disturbance is getting closer, isn’t it? Perhaps we don’t always think about this consciously when we flip to a new poem in a journal, but it probably has some effect on you on a subconscious level.

What Should We Steal?

- Balance concrete elements with abstract ones. If you’re going to be a little experimental with your plot, make sure other facets of your work are easily accessible in some way.

- Allow the structure of your work to add suspense all on its own. The way your work looks can add suspense as much as the words you’re using.

Poem

2013, Gymnastic Wordplay, Natalie Shapero, Ohio State, The Awl

Title of Work and its Form: “Anything Helps,” short story

Author: Jess Walter (on Twitter @1JessWalter)

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in December 2011’s Issue 39 of McSweeney’s, one of the top journals around. You can purchase a back issue of the journal if you like; they will appreciate it. “Anything Helps” was subsequently chosen for Best American Short Stories 2012 by Heidi Pitlor and Tom Perrotta; you can find the story in the anthology.

Bonuses: Here is what blogger Karen Carlson thought of the story. I love that she points out a slight similarity to “What You Pawn I Will Redeem.” Here is a Daily Beast interview with Mr. Walter. Charles E. May offers some interesting thoughts about the story, as well.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Fundamentals

Discussion:

So…Bit has some problems. He’s a homeless alcoholic who lost the mother of his child to an overdose. He was kicked out of a shelter for breaking the rules against drinking, blaspheming and fighting. His son is in foster care and Bit really isn’t allowed to visit much. Bit likes to panhandle on the side of the road and the story gets going when a rich guy gives him a twenty-dollar bill. Bit buys a copy of the last Harry Potter book, hoping to give it to his son, but the foster mother doesn’t approve of magical, mythological stories on a religious basis. In the climax, Bit sees his son; the kid loves him, but there is so much sadness and tension in their relationship. Bit resumes his offramp panhandling and begins reading the book as a way of somehow being close to his son.

Okay, so this story made me think of Saturday Night Live’s Stefon.

As he might say, “This story has EVERYTHING.” Seriously, look at how many traditional elements this story contains:

- Clear protagonist: Bit

- Clear antagonist: Bit (the foster mother?).

- Big stakes: Bit wants to give his son the book.

- Inciting incident: Bit gets the twenty dollars that allows him to buy the Harry Potter book.

- Climax that reflects upon the themes of the story: Bit meets with his son Nate.

- Adherence to the Unity of Time, pretty much: Everything is in present tense, following him through a VERY IMPORTANT DAY™.

- Internal conflict: Alcoholism, lack of ability to get it together.

- External conflict: Strangers will or won’t give him money. Cater kicks him out of the shelter.

- Interesting setting: a homeless shelter, highway offramps.

- Recurrence of title at important points in the story: “Anything helps.”

- Adherence to Freytag’s pyramid: events of increasing importance culminating with a meaningful climax related to theme and a denouement that offers some clue as to how the protagonist has changed as a result of the story’s events.

There’s no official checklist to tell you what should be in your story. And even if there were, I don’t think you can assemble a story in the way you would assemble an engine. But perhaps it will benefit you to look back at your work and do a mental double-check to see if you’ve equipped your piece with enough of the elements that make writing great. (I’m thinking that “Speckle Trout” is another story that is put together incredibly well.)

Mr. Walter also happens to employ a technique that stands out. The dialogue is not in quotation marks. So he’s “broken a rule” there. What he has really done is employ a stylistic choice. Leaving out the quote marks makes it a little “harder” for the reader to understand when a character is talking and what they were saying. After all, those marks are there as a quick prompt to your brain, right? They separate dialogue from everything else. Perhaps Mr. Walter forces the reader to think about and examine the story more carefully.

Perhaps Mr. Walter is thinking of the page in the same way that a painter considers a canvas. Maybe he just liked the way the story would look without all of the quotation marks. Writers have lots of options open to them and a toolbox that overflows. You can move words around on the page, use italics, change fonts, change text color, write in different languages, add graphics…the list is exhausting. You can leave out the quotation marks in order to lend the piece a different feel, but do so judiciously; isn’t your first duty to helping the reader understand your intent? I have seen some cases of quote mark-less writing that is not as clear as “Anything Helps.” Be sure that the reader doesn’t need to wonder what is dialogue and what is not.

Here; I’ll make up an example from a pretend story influenced by the fact that I saw my first episode of Bridezillas the other day.

Johanne led Ed into the tattoo shop and told him to take his shirt off sit down. She said, we’re getting matching tattoos, but you have to be blindfolded.

Ed sat down as Johanne put the handkerchief over his eyes. He asked, what are we getting? I don’t mind another tattoo, but I’m curious. The first one wasn’t so bad, but it was still painful. The artist shaved a spot on his chest.

Don’t you worry, Johanne said, reclining into the other chair as Jim the tattoo artist put the stencil on her inside thigh. You’ll love it.

Jim looked at Johanne, kissing her as he said, We’re going out next week, right? It won’t bother Ed at all.

Fifteen minutes later, Johanne revealed her tattoo: 100% Certifiable. Ed was terrified as Johanne pulled up his shirt, saying I don’t want people to think I’m certifiable.

No, you have something else, she said. Property of Johanne.

Ed saw the brand on his chest and somehow didn’t run screaming and do whatever it took to get away from Johanne.

There are a few places where you could be confused as to whether or not the character is speaking or the narrator. (And you should be confused that the guy really did marry that woman.)

What Should We Steal?

- Look back at your story to see if you’ve hit enough of the marks that make a piece of writing great. When you write an e-mail, don’t you sometimes read it over to make sure that you’ve been clear as to what you want? This is the same principle.

- Diverge from the standard conventions of prose, but do so judiciously. You are an artist, dear writer. Instead of covering a canvas with paint, you do so with words.

Short Story

2011, Best American 2012, Fundamentals, Harry Potter, Jess Walter, McSweeney's

Title of Work and its Form: Issue 1 of “Jupiter’s Legacy,” comic book

Author: Written by Mark Millar (on Twitter @mrmarkmillar). Art by Frank Quitely. Colors and letters and design by Peter Doherty.

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The issue was published in April 2013 and can be purchased at any fine comic book store, including Oswego, NY’s The Comic Shop.

Bonuses: Here is the official Image Comics listing for the issue. Here is a Comics Alliance analysis by David Brothers with which you may or may not agree. Here is an interview Mr. Millar did with Comic Book Resources in which he discusses the series.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Perspective

Discussion:

It’s 1932. Sheldon Sampson lost (almost) all of his money in the stock market crash and is desperately looking for a way to improve his own prospects and that of the whole country. He has been seeing an island in his dreams and charters a ship to take him there. He and his wife acquired superhero powers on that island; Sheldon doesn’t talk about how. Sheldon is an idealist. A good man. Cut to March 2013. Sheldon’s children aren’t so great. Brandon and Chloe Sampson are socialites who live in the shadow of their parents’ accomplishments. The young people party and indulge in sex and drugs, lamenting that “the great battles are well and truly over.” The older generation debates what must be done to help the country, but Sheldon and his brother have opposing ideas. (Source of conflict!) At the end of the issue, Chloe has overdosed on some particularly potent drugs.

As I noted in my previous GWS essay about a comic book, I love graphic storytelling, but time constraints have prevented me from sending out scripts. I’m not sure the connection between the literary and comic book worlds is strong enough. Oh well; that’s what the future is for. Speaking of the future, Jupiter’s Legacy seems to straddle different time periods. Sheldon acquires his powers and helps the country recover from the Great Depression. He and his group are facing the aftermath of the problems that happened in the first decade of the twenty-first century. And if you want to be picky, we have to mention the titular Roman deity. If you’ll recall, Jupiter is the king of all of the gods; he hurled lightning bolts from the sky. He was worshipped most by the upper class of Roman society, who believed his intercession explained their supremacy. No matter the time period, Mr. Millar is using each situation to reflect on the others. Jupiter was the savior of the Romans, Sheldon, et. al. saved the United States in the thirties and the next generation…well, what will they do? Mr. Millar is playing with big, classic themes here! This is a very powerful technique; when you examine the same situation through several different angles, you gain a lot of perspective. Think of Citizen Kane; the reporter is trying to figure out what Kane was all about by talking to a number of people about the man’s life. Think of Rashomon. The same event is examined from different perspectives; the similarities and differences in their accounts lend characterization and advance the plot in a way that creates suspense. In the case of Jupiter’s Legacy, societal problems are being engaged in a time of optimism and a time of apathy. As the series progresses, Mr. Millar will no doubt continue to juxtapose the two time periods. In doing so, we’ll learn a little bit about what he thinks of our society.

Another part of Jupiter’s Legacy that I admire is the way that Mr. Millar focuses on the conflict between the characters. He could easily show us how the Sampsons gained their powers—and perhaps he will—but he chose to plant several big conflicts in the first issue:

- How Americans responded to the Depression in contrast to how they have dealt with recent struggles

- Celebrity society vs. meaningful existence

- The moral obligations of the individual to the society

- How the child of a very “successful” person can “succeed” on their own terms. (Success is a subjective term, of course.)

Now that Mr. Millar has set up all of these conflicts, he can play with them throughout the rest of the series. Indeed, there is a battle sequence that takes up several pages, but Mr. Millar doesn’t include it only for the “fun” of it. Remember, we’re much more curious about the WHY than the HOW.

What Should We Steal?

- Examine the same idea through different lenses and different perspectives. If you want to get a good idea of what a person is really like, you might ask several of the people they know. The same principle can apply to story.

- Focus on the conflict instead of the spectacle. (Most of the time.) The big reveals in your story will mean more once we care about your characters.

Comic Book

2013, Frank Quitely, Image Comics, Mark Millar, Narrative Perspective, Superheroes

Title of Work and its Form: “My Uncle, My Brother,” creative nonfiction

Author: Debie Thomas

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece debuted in the Winter 2011 issue of The Kenyon Review, a truly great journal. You can purchase a back issue from those fine folks. Or you can take advantage of the public library system (the best investment in human history) and read the piece through EBSCO.

Bonuses: Here is what blogger Maggie McNamara thought of the piece.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Drama Without Melodrama

Discussion:

It began when Ms. Thomas was nine. “Uncle” finds her while she is playing hide-and-seek with friends and lifts her up and kisses her in an improper manner. During successive visits, Uncle continues to act improperly. Ms. Thomas grew up in the United States in a traditional Indian home and is taught, directly and indirectly, those sorts of things are both wrong and things to keep secret. Ms. Thomas describes the home and its culture, in which “there is nothing either good or powerful about needs and desires.” Then “Achachen” shows up when Ms. Thomas is twelve. In the generic, an achachen “is the Malayam title for every kind of older brother.” Not young enough to be an equal and not old enough to be an uncle. Achachen has been taken in by Ms. Thomas’s family and is increasingly improper after Ms. Thomas shared her diary (confessing the actions of Uncle). Ms. Thomas disassociates during these episodes, feeling “a vast, gray apathy.” This psychology, she learns later, is normal for men and women who experience such abuse. At the age of twenty-two, Ms. Thomas married a premed student from Calcutta who she had never met. Ms. Thomas is very careful to emphasize that her husband is “kind and attentive” and is a good man, but she does ask, “What does it mean, as a survivor of abuse, to forge a monogamous sexual relationship with a man my father handed me to, a man who was essentially a stranger when we first slept together?” Ms. Thomas considers all of these experiences in the context of her Indian upbringing and American life and the utterly human need to maintain one’s dignity and sense of self.

So this is a very powerful piece of creative nonfiction that deals with themes that are uncomfortable and necessary. Is there a topic that elicits more emotion than child abuse? (The older I get, the sadder it makes me. Thankfully, I’ll probably never have kids, so I won’t have to worry about such problems in a more personal manner.) I can’t imagine a better way of dealing with the elephant in the room than the way Ms. Thomas does. She does not flinch from describing the acts, at least enough for us to know what is going on in the narrative. Ms. Thomas could have elicited far more emotion if she went into further and more graphic detail, but she doesn’t. Why? Because she wants to EARN the audience reaction. Ms. Thomas is going for drama, not melodrama. She is far more interested in informing the reader about the aftermath of what happened. This is far more engaging and special than simply presenting details that are guaranteed to make the reader sad and angry. The reader wants to learn about Ms. Thomas and how she dealt with everything and what she thinks it means…these are unique details that only she can communicate. The principle carries over to fiction; the reader wants to see how characters cope with extreme situations…not just the situations.

Whether or not it was intentional, the structure of Ms. Thomas’s piece mimics the psychological response that she had in the wake of the abuse. Ms. Thomas cuts the reader to the bone emotionally and then “disassociates.” She pulls back, allowing you to contextualize what you’ve read. (And she’s killer with the sentences that end each section.) This is the same technique used in…well, everything great. Think about an action movie. There’s an awesome action sequence…followed by a quiet scene. More big action…then some quiet. In a piece of drama (not melodrama), the audience needs a chance for relief and to think about what is happening, whether they do so consciously or otherwise.

And look at the stellar opening of the piece. Ms. Thomas opens with a childhood game of hide-and-seek. She’s crouched behind a rhododendron bush, trying not to be found. Then she is found by Uncle, who kisses her in an improper manner. Why is this scene great?

- The opening scene reflects one of the themes of the piece. People who do the kind of unpleasant acts in question seek children out and hide their actions.

- Ms. Thomas is engaged in a very childlike activity, immediately contrasted with an adult one. There’s the same contrast between happy and sad.

- The young Ms. Thomas placed herself in the hiding place, relating to the sense of self-blame she feels later in life.

- Immediately after the improper kiss, Ms. Thomas slides right into a meaningful discussion of the place of men in Indian culture.

…And this is all in the first three paragraphs! Ms. Thomas begins with a crucial scene that contains all of the important themes of the larger work. It’s a strange comparison, but it reminds me of what happens in the beginning of each Lethal Weapon sequel. The slam-bang opening scene ties into the relationship between Riggs and Murtaugh in some way and communicates where the characters are and so on.

What Should We Steal?

- Create drama instead of melodrama. Drama is all about presenting a unique story populated by human beings. Melodrama is getting a strobe light and shouting, “Hey! Look at this! Over here! This stuff is crazy!”

- Offer your reader a chance to contextualize the high points of your narrative. If you got married every day, it wouldn’t be special, now would it? (I suppose it depends on the quality of the gifts you get.)

- Employ all of the tools in your kit, especially in the beginning of your work. Introductions should be potent! They must grab attention and prepare the reader for what will follow.

Creative Nonfiction

2011, Debie Thomas, Drama Without Melodrama, Kenyon Review, Ohio State

Title of Work and its Form: “Miracle Polish,” short story

Author: Steven Millhauser

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story premiered in the November 14, 2011 issue of The New Yorker. As of this writing, you can read “Miracle Polish” right here. Heidi Pitlor and Tom Perrotta chose the story for the 2012 edition of Best American Short Stories.

Bonuses: Here is what Short A Day thought about “Miracle Polish.” Here is a lengthy and interesting interview with Mr. Millhauser over at BOMB. Here‘s “A Voice in the Night,” another Millhauser story from The New Yorker.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Momentum

Discussion:

Inciting incident: A peddler shows up at the first person narrator’s home. The old man is selling Miracle Polish, a product that will put a special shine on any mirror in your home. The narrator watches as the peddler leaves; there’s a perfectly appropriate moment of oddness as the salesman locks eyes with the narrator before leaving. The narrator cleans a mirror with the polish…he looks younger and fresher. His girlfriend Monica is tired, too. She doesn’t seem to like the happier-looking Monica she sees in the mirror. The narrator soon puts mirrors on every wall in his home, causing tension in his relationship with Monica. She believes that he prefers the more youthful version of her that he sees in the mirror. There’s a perfectly inevitable conclusion in which Chekhov’s mirrors are dealt with in proper fashion.

The story reminded me a bit of an episode of The Twilight Zone, which is a massive compliment. Mr. Millhauser creates a through-a-mirror-darkly magical realism world in the same way that Rod Serling did in many of the Twilight Zone scripts. Everything in the narrator’s world is perfectly normal…except for the Miracle Polish. There’s the sense of impending danger; we’re led to wonder why the peddler locked eyes with the narrator in such a strange way. There’s a “hook” in the beginning that looms over the entire story. That second bottle of Miracle Polish…the peddler advised the narrator to buy one, but he didn’t. This hook is paid off in the final paragraph of the story. As in the best Twilight Zone scripts, the “strange” things, the magical fantasy, all relate to the rest of the story and its theme. That unpurchased second bottle also creates a kind of countdown…will the narrator run out of Miracle Polish? What will happen when he does?

Mr. Millhauser also creates characters that truly belong in this story. The middle-aged man feels run-down and doesn’t seem to like what he has become. He’s just the kind of guy who could use a look in the mirror. So Mr. Millhauser offers him a particularly clear look into one. His girlfriend Monica has a habit of “assessing her looks mercilessly.” As she is first described, I thought Monica was a teenage young woman. Instead, she merely has a few of those qualities. It’s been quite some time since I was around a teenage young woman, but I’m guessing mirrors still play an important role in their lives. These two characters are confronted by mirrors; one likes the reflection and the other doesn’t. That means tension! Whoo hoo!

Another tactic Mr. Millhauser employs is apparent when you look at the left margin of the story. One of the problems I have is deciding which parts of the story to render in scene. Mr. Millhauser creates an around-the-campfire feeling by offering long paragraphs and sliding through time a great deal. Which scenes are absolutely necessary? We need to see the narrator and Monica looking into the mirrors. And arguing about the mirrors. And what happens during the climax, when the conflict comes to a head.

What Should We Steal?

- Relate the ending of your story to its beginning. Your story should make some kind of unified comment about humanity or the world or whatever, right? The theme should be as consistent as the characters and setting.

- Give your characters what they deserve. Four horny teenage boys want to have sex? Make them forge a pact with each other to get laid. Your character is a liar and manipulator? Put him or her in a political drama.

- Flatten out the left margin. You can create narrative momentum by focusing less on describing scenes and more on describing story.

Short Story

2011, Best American 2012, Narrative Momentum, Steven Millhauser, The New Yorker, The Twilight Zone

Title of Work and its Form: “Vectors 3.1: Aphorisms and Ten Second Essays,” poem

Author: James Richardson

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece made its premiere in the Spring 2011 issue of Hotel Amerika. After being awarded a Pushcart Prize, the piece was included in the award’s 2013 anthology.

Bonuses: Here is a pretty comprehensive introduction to Mr. Richardson’s work over at Writing Without Words. Here is a poem by Mr. Richardson that was included in Garrison Keillor’s The Writer’s Almanac.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Classic Forms

Discussion:

This work is a little difficult to categorize. (Poem or work of nonfiction?) Through the course of forty-two aphoristic statements, Mr. Richardson offers interesting and personal advice for living and productive thought. These statements come from nature and modern life and seemingly whatever the accomplished author wished to communicate. Appropriately, some of the statements seem somewhat redundant; advice often seems this way.

7

Even words are beyond words

Mr. Richardson releases the statements in firehose fashion, allowing the reader to wallow in the complicated thoughts. What is the effect? I think the unrelenting sparseness forces the reader to select which aphorisms he or she appreciates most. After all, our parents and other authority figures tell us a million things; how many concise statements really stick with us?

One thing that I’ve learned from teaching is that some folks are unwilling to admit that they don’t know exactly what a word means. Under most circumstances, this isn’t a big deal. (Um…if you’re a lawyer, you should really know what a “deposition” is and so on.) We don’t go to dictionary.com for definitions. We go to word nerds. This is what Mr. Richardson means by “aphorism:”

Any principle or precept expressed in few words; a short pithy sentence containing a truth of general import; a maxim.

The aphorism is a classic form; people have been sharing pithy and concise advice for thousands of years. Why bother continuing to compose such works? Well, for one thing, we all want to read Mr. Richardson’s spin on the form. Further, Mr. Richardson is a contemporary writer who inherently has very different experiences from those who lived hundreds or thousands of years ago. Those who composed the aphorisms in the Christian Bible lived long before the invention of audio recording equipment. (Obviously.)

Check out aphorism #17:

You try to take it back, but the tape in reverse is unintelligible.

The development of new technologies allows for new metaphors to inhabit classic forms. If a work of scripture were written today, what would that look like? What about an epic poem? A Socratic dialogue? Would the last form be done in the form of text messaging?

Aphorisms, as Mr. Richardson demonstrates, are very much a form of poetry. Mr. Richardson only gives himself several words to communicate a big idea. Isn’t this the work of poetry? To address huge concepts in as few words as possible? (You know…the “right” words?) Isn’t this a principle we can apply to any piece of writing? A memo, a letter to the gas company, the climax of a short story? Even though it’s more incumbent upon poets to be concise, writers in all forms can and should borrow this poetic technique.

What Should We Steal?

- Tackle a classic form with a contemporary mindset. Shakespeare would have used cell phones in his plays if he were still alive and writing. (So would Seinfeld, for that matter.) How might recent developments shape a classic form?

- Borrow the toolbox of the poet, no matter the form you’re using. If you’re listening to “Tomorrow Never Knows,” okay, fine; the “dream” is the point. In a narrative, the dream must simply be another facet of the world and characters you create.

Poem

2011, 2013 Pushcart, Aphorism, Classic Forms, Hotel Amerika, James Richardson

Title of Work and its Form: “Volcano,” short story

Author: Lawrence Osborne

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story premiered in Issue 47 (Spring 2011) of Tin House, one of the best journals around. “Volcano” was subsequently chosen for Best American Short Stories 2012.

Bonuses: Karen Carlson shares her thoughts on the story; I love that she both appreciates and dislikes the story. That’s the mark of complicated criticism! Charles E. May, as always, has some important ideas about the story. Here is the NYT review of Mr. Osborne’s latest book, The Forgiven.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Use of Dreams

Discussion:

Martha Fink, a forty-six-year-old attorney, is going through a rough time in her life. She divorced her cheating husband six months ago and is still working through her understandable anger and confusion. She packs up and heads off to Hawaii on her own. As luck would have it, Martha books a room at a resort, “run by two gay dancers” that is “next to an active volcano.” Martha doesn’t much like the resort’s regular programming; the people aren’t quite her style and she doesn’t like the lucid dreaming seminar she signed up for. The Dream Express group is intended to allow her to remember and change her dreams. She’s given drugs and a set of magic goggles to help her in that respect. They don’t exactly work. Martha decides to ditch the regular programming and rides her bike around the beautiful island. She finds a hotel and a hotel bar that is tucked away in a remote location. There’s a man at the bar, a retired geologist, who appreciates her as a woman-something that has been a challenge for her because of the whole husband thing. After having one drink (and introducing herself as “Martha Prickhater”), she heads out on a bike ride. Now it’s too late for her to go back to her resort. She returns to the hotel/bar and has drinks with the geologist and decides to take a room in the hotel. After going into her room and closing the door, Martha changes her mind and finds the geologist. They have sex in the dark. In the last paragraph, we get a carefully detailed description of the act and Martha’s real-time thoughts about it. Dreams and the ability to control dreams play a big role.

What sets this story apart? It’s a stellar example of the third person limited point of view. Mr. Osborne offers us deep access to Martha’s thought and this access is crucial to the ending of the story. The reader may have been jarred had Mr. Osborne started out with a wider third person before zooming in on Martha’s consciousness. This is Martha’s story, so the author takes her hand and remains with her throughout. This is also fitting because of the themes of solitude and disconnection from society. Preventing the reader from accessing the thoughts of others allows him or her to understand Martha’s point of view. She’s in her own head all the time and we share the experience with her.

Choosing the right point of view can be problematic. I’m thinking of one of my current story ideas and I’m not sure which way to go. Perhaps the solution can be found in thinking of the ending of the story and working backwards. Mr. Osborne’s ending requires a blending of firmly grasping reality and slipping slightly into dream consciousness. In the first person, this may be difficult because a first-person narrator could not offer objective commentary. In the second person, the narrator would have to contend with the consciousness of the “you” and that of the reader. The third-person limited is just right because it allows Mr. Osborne the best of both worlds: he can tell you what is really happening and tell you what is happening in Martha’s head.

Mr. Osborne also offers a master class in how to write dreams. We’ve all been warned to avoid the cliche it-was-all-a-dream ending. Why? Because it’s a cheat. Mr. Osborne warps reality in a meaningful manner. Martha has dreams in the first half of the story and these do indeed illuminate her psychology for the reader. Martha is forced to confront her trouble relating to others (a central character facet that leads to the conclusion). The dreams are also not terribly abstract. Mr. Osborne isn’t putting you into the role of a psychiatrist by offering some way-out-there descriptions of things. A lesser writer (such as myself) would make the dreams so strange that the reader would be forced to take out pad and pencil and figure out what is going on. Further, Mr. Osborne us careful to let us know when Martha is dreaming and when she is not. Some writers would not be as vigilant in using the key words and phrases: “began to dream,” “awoke,” “got up,” “wrote down her dream straightaway.”

Mr. Osborne is also very careful to establish the “rules” of the lucid dreaming workshop. When Martha reaches for the wall in the end of the story, it means something to us. Why? Because the lucid dreaming expert person told us that rubbing a rough surface will change the dream immediately, and then Mr. Osborne has Martha do just that during one of her less-than-satisfying dreams in the resort. The reader will follow you wherever you want to go, but you need to establish the specific rules of the world you’re creating. Mr. Osborne follows his own rules, which is important when he gets to the ending of the story. He gets a TINY bit abstract and that’s okay. It’s the end of the story and Martha is undergoing a…very important experience. The reader understands the significance of rubbing a rough surface, so it means an awful lot.

What Should We Steal?

- Choose your point of view by working backwards. If you’re not sure which POV to use, consider which would facilitate the ending you have in mind.

- Employ dreams as a tool, not a story element unto themselves. If you’re listening to “Tomorrow Never Knows,” okay, fine; the “dream” is the point. In a narrative, the dream must simply be another facet of the world and characters you create.

- Establish the unique rules of your world very quickly and adhere to them. Think of something like Star Trek: The Next Generation. (I do this all the time.) Does it make sense that the Enterprise can go faster than the speed of light? Sure. The writers established the “how” of the warp drive and adhere to the rules of the technology very closely.

Short Story

2011, Best American 2012, Lawrence Osborne, Tin House, Use of Dreams, Volcano

Title of Work and its Form: “Creation Myth,” nonfiction

Author: Malcolm Gladwell (on Twitter @Gladwell)

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece debuted in the May 16, 2011 issue of The New Yorker. You may be able to find it here if you’re a subscriber. The piece was also selected for the 2012 edition of Best American Essays.

Bonuses: Jealousy alert! Mr. Gladwell appeared on The Colbert Report. Here is the archive of Mr. Gladwell’s work for The New Yorker. Here is a fun bur brief profile/interview of Mr. Gladwell that was published by AllThingsD.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Diction

Discussion:

I’ve always been a sucker for the story: Long ago in a valley far, far away, the rock star engineers of Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center created just about everything we associate with modern computing. The graphical user interface. The mouse. The laser printer. The problem? Xerox PARC never capitalized upon the bounty created in their labs. Mr. Gladwell begins the piece by reminding the reader of the biggest legend relating to Xerox PARC. The story has been that Steve Jobs’s 1979 visit to the lab was the catalyst for Apple’s later success. Jobs glimpsed the future and snatched it from Xerox’s grasp. This impression is not entirely true. As Mr. Gladwell points out, “the truth is a bit more complicated.” With the subject and structure established, Mr. Gladwell spends most of the piece discussing his real point: history shows us that the innovative don’t always succeed because they may not have the entrepreneurial skills needed to turn the dreams into reality. “Visionaries,” he points out, “are limited by their visions.” Mr. Gladwell uses some diverse examples; military tactics developed differently in Israel and the Soviet Union and the United States because of the resources and capabilities available to each. Mr. Gladwell brings in interviews with PARC engineers and other people who are important to the story. The climax seems to come in an apt reference to the Rolling Stones. The boundless creativity of Mick Jagger needs a pragmatist like Keith Richards to “turn off the tap.” (It is indeed strange to think of Keith Richards as the practical one.)

This piece reflects Mr. Gladwell’s usual M.O. And it’s a wonderful M.O. He is explicitly SHOWING instead of TELLING. A lesser writer (such as myself) would simply say, “people with great imagination must involve themselves with folks who can help restrict their creativity and channel it into something productive.” Instead, Mr. Gladwell wraps the lesson in a fascinating story from the past. (I love learning about early computing.) In his books and articles, Mr. Gladwell certainly does offer many practical lessons and frameworks through which we can better understand the world, but he never allows the lesson to get in the way of his stories. Even if it is explicit, the “moral” of your story should be implicit in the work. Mr. Gladwell has such a wide readership because he weaves together interesting stories that are meaningful. He doesn’t simply point his rhetorical finger at you and tell you what to believe.

Another thing that I’ve noticed about Mr. Gladwell’s work is that he does very little “throat clearing.” Instead of starting out with a paragraph of preamble, the writer gets right to work:

In late 1979, a twenty-four-year-old entrepreneur paid a visit to a research center in Silicon Valley called Xerox PARC. He was the co-founder of a small computer startup down the road, in Cupertino. His name was Steve Jobs.

Mr. Gladwell’s clear sentences reveal the joy he takes in telling the story and in sharing information with others. I suppose it’s hard to quantify, but it always seems to me as though the gentleman is gleeful in sharing knowledge with his reader. Many of the sentences are short and descriptive, but Mr. Gladwell flexes his poetic muscles at times:

One PARC scientist recalls Jobs as “rambunctious”—a fresh-cheeked, caffeinated version of today’s austere digital emperor.

This is the legend of Xerox PARC. Jobs is the Biblical Jacob and Xerox is Esau, squandering his birthright for a pittance.

He had brought a big plastic bag full of the artifacts of that moment: diagrams scribbled on lined paper, dozens of differently sized plastic mouse shells, a spool of guitar wire, a tiny set of wheels from a toy train set, and the metal lid from a jar of Ralph’s preserves.

The above sentence particularly proves my point. Mr. Gladwell’s prose is highly utilitarian, but when he diverges from his pattern, there’s a good reason. A lesser writer would have included far less description of the “artifacts.” Every choice you make in your work-your diction, your structure-should be made in the service of the whole. Mr. Gladwell’s goal (at least one of them) was to impart his lesson about the proper care of creative minds. It was therefore a felicitous choice to make his sentences utilitarian and to very quickly lay the foundations of the stories that would illuminate his point.

What Should We Steal?

- Prioritize storytelling over moralizing. Getting a message out there is important; it’s why many of us become writers in the first place. Attracting and maintaining the attention of the reader is just as important, if not more so.

- Favor clarity of sentences over poeticism. This idea is an especially good one for journalists and nonfiction writers.

Nonfiction

2011, Best American Essays 2012, Diction, Malcolm Gladwell, The New Yorker