The Great Writers Steal Podcast: Giano Cromley, author of What We Build Upon the Ruins

Download the podcast

Visit Mr. Cromley’s web site:

http://www.gianocromley.com/ Continue Reading

Download the podcast

Visit Mr. Cromley’s web site:

http://www.gianocromley.com/ Continue Reading

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

I don’t happen to know Jan Bowman very well, but it is very clear that she is a very good literary citizen and a dedicated writer. She cares about the community, but more importantly, she cares about trying ever harder to improve her own work. In 2015, Evening Street Press published Flight Path & Other Stories. I’m sure you will enjoy Ms. Bowman’s insights into her own work; why not consider picking up a copy directly from the publisher?

Yes, you may wish to read 10,000 words in which Ms. Bowman describes the methods by which we can add depth to our characters. Instead, I am curious about the tiny choices that Ms. Bowman made when she wrote the title story of her collection. Let’s take a look at her way of thinking and see how it affects our own! (Don’t worry…I made sure that you’ll still get some use out of the interview if you haven’t read the story.)

Continue Reading

Show Notes:

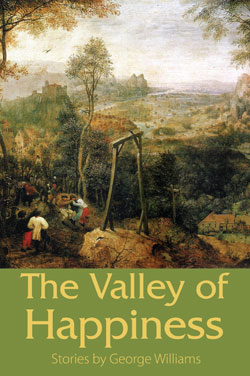

Enjoy this interview with George Williams, author of The Valley of Happiness, a collection published by the fine people at Raw Dog Screaming Press.

Take a look at Mr. Williams’s Goodreads page:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/4875077.George_Williams

Order your copies of his Raw Dog Screaming books from the publisher:

http://rawdogscreaming.com/authors/george-williams/

Here is a text interview Mr. Williams granted to D. Harlan Williams:

http://www.dharlanwilson.com/dreampeople/issue35/interviewwilliams.html

Mr. Williams refers to a book about the Shakespeare Authorship question. He’s talking about James Shapiro’s excellent book, Contested Will:

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/mar/20/contested-will-who-wrote-shakespeare

Here’s “The Magpie on the Gallows,” the painting that Mr. Williams chose for the cover of his collection:

Like writing exercises? Here is one inspired by the conversation I had with Mr. Williams:

Visit my website: https://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Like me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Follow me on Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Many thanks to the Library of Congress for their beautiful public domain images:

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2012649048/ (Savannah during the Civil War era!)

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa1998006340/PP/ (Voters in 1940 North Carolina waiting to cast their ballots!)

Show Notes:

Enjoy this interview with Christy Crutchfield, author of How to Catch a Coyote, a novel published by Publishing Genius Press.

Find out more about Christy Crutchfield at her web site.

http://www.christycrutchfield.com

Order your copy of her book from her publisher:

http://www.publishinggenius.com/?p=3347

Or you can order your copy from your local indie bookstore:

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780988750388

Or you can order the book online the old-fashioned way:

http://www.powells.com/biblio/62-9780988750388-0

Visit my website: https://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Like me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Follow me on Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Many thanks to the Library of Congress for their beautiful public domain image:

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/nclc.00097/

2014, Christy Crutchfield, How to Catch a Coyote, Publishing Genius Press, The Great Writers Steal Podcast

Show Notes:

Enjoy this interview with Wendy J. Fox, author of The Seven Stages of Anger, a short story collection published by Press 53.

Purchase The Seven Stages of Anger:

http://www.press53.com/bioWendyJFox.html

Find out more about Wendy J. Fox:

http://www.wendyjfox.com/

Visit the web site of BookBar:

http://www.bookbardenver.com/

Like the bookstore on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/BookBarDenver

Book You Should Buy: Backswing by Aaron Burch

http://www.queensferrypress.com/books/backswing.html

Find out more about Aaron Burch:

http://aaronburch.tumblr.com/

Better Know a Buckeye: Allison Davis

http://www.allisondavispoetry.com/

Purchase Ms. Davis’s book:

http://www.kentstateuniversitypress.com/2012/poppy-seeds/

Website: https://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Aaron Burch, Allison Davis, Backswing, Carrie White, Ohio State, Press 53, Wendy J. Fox

Enjoy this interview with Jac Jemc, author of A Different Bed Every Time, a short story collection published by Dzanc Books.

Purchase A Different Bed Every Time:

http://www.dzancbooks.org/our-books/a-different-bad-everytime-by-jac-jemc

Find out more about Jac Jemc:

http://jacjemc.com/

Show Notes:

Visit the web site of Women & Children First:

http://www.womenandchildrenfirst.com

Like the bookstore on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Women-Children-First-Bookstore/8326741337

Book You Should Buy: Fobbit by David Abrams

http://www.davidabramsbooks.com/

Buy the book here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/fobbit-david-abrams/1109170055?ean=9780802120328&itm=1&usri=fobbit

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780802120328/david-abrams/fobbit

Better Know a Buckeye: Erin McGraw

http://www.erinmcgraw.com/

https://www.greatwriterssteal.com/2013/01/26/what-can-we-steal-from-erin-mcgraws-punchline/

Purchase Erin’s books:

http://www.amazon.com/Erin-McGraw/e/B001ITRD0W/ref=dp_byline_cont_book_1

Website: https://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

David Abrams, Dzanc Books, Erin McGraw, GWS Video, Jac Jemc, Ohio State, The Great Writers Steal Experience

Title of Work and its Form: Fish Bites Cop! Stories to Bash Authorities, short story collection

Author: David James Keaton (on Twitter @spiderfrogged)

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: I was amused by the playful manner in which Mr. Keaton tells his fans how they can get the book, so I share it here:

If you’re looking to buy it (did I already post these retailers somewhere? oh, well), here’s a link to the Comet Press website, as well as links to Barnes & Noble (for locals), Carmichael’s Bookstore (for locals), Powell’s, Indiebound, and Amazon. I listed those in order of preference. Buy it from the publisher or the real stores first, unless you need it on Kindle. Who knows where that Amazon money goes.

Hey, Fish Bites Cop! has a book trailer!

Bonuses: Here is “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel,” one of my favorite stories from the book.

Want to see Mr. Keaton read his work? Sure, you do:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing:

Discussion:

Mr. Keaton is very clear with regard to the theme of his collection. Each of these stories does indeed involve “authorities.” There are police officers, the captain of a fishing vessel, high school coaches, paramedics…Mr. Keaton may be very focused, but he doesn’t have a one-track mind. Indeed, Fish Bites Cop! is bursting with creativity; the gentleman doesn’t go more than a page or so without turning an underlinable phrase or making some kind of connection that may elude most readers. (Why else do we read, after all?)

Here is the book’s table of contents. (I added the POV and page counts myself, of course.)

| Title | POV | Number of Pages |

| Trophies | 3rd | 2 |

| Bad Hand Acting | 3rd | 8 |

| Killing Coaches | 1st | 8 |

| Schrödinger’s Rat | 1st (we) | 13 |

| Life Expectancy In A Trunk (Depends on Traffic) | 1st | 8 |

| Greenhorns | 3rd | 12 |

| Shock Collar | 3rd | 4 |

| Third Bridesmaid From The Right (or Don’t Feed The Shadow Animals) | 1st | 11 |

| Burning Down DJs | 1st | 6 |

| Shades | 3rd | 6 |

| Three Ways Without Water (or The Day Roadkill, Drunk Driving, And The Electric Chair Were Invented) | 3rd | 11 |

| Heck | 3rd | 4 |

| Do The Münster Mash | 3rd | 4 |

| Either Way It Ends With A Shovel | 3rd | 14 |

| Castrating Firemen | 1st (directed at silent interlocutor) | 5 |

| Friction Ridge (or Beguiling The Bard In Three Acts) | Play | 14 |

| Doppelgänger Radar | 3rd | 4 |

| Queen Excluder | 3rd | 12 |

| Don’t Waste It Whistling (or Could Shoulda Woulda) | 1st (directed at silent interlocutor) | 3 |

| Three Minutes | 3rd | 3 |

| Bait Car Bruise | 1st | 3 |

| Clam Digger | 1st | 8 |

| Swatter | 1st | 8 |

| Three Abortions And A Miscarriage (A Fun “What If?”) | 3rd | 14 |

| Catching Bubble | 3rd | 3 |

| Doing Everything But Actually Doing It | 3rd | 9 |

| The Living Shit (or Mosquito Bites) | 1st | 6 |

| Warning Signs | 3rd | 3 |

| The Ball Pit (or Children Under 5 Eat Free!) | 3rd | 6 |

| Nine Cops Killed For A Goldfish Cracker | 3rd |

Mr. Keaton bowls us over with at least one lesson: like him, we should write a lot. Now, I’m sure he has some sort of science fiction-type device that gives him 30 hours a day instead of our 24, but we really have no excuse. I know…I know…you would finish a story, but…

There’s only one solution to these very common problems: Just write stuff. Duh. We all know we should just shut up and finish a piece, but that can be hard to do sometimes. But do it anyway. Just look at all of the stuff that Mr. Keaton has published in only a few years. So let’s get back to work, right?

Mr. Keaton also seems to enjoy a technique that reminds me of the work of Lee K. Abbott in some ways. Check out some first sentences from Fish Bites Cop!:

“She was sure one of them was watching her.”

“Before the night ends with me crashing through the woods in a stolen police car, I’ll drive around stuck on one thought.”

“There were sitting down to dinner when the phone rang.”

“I will leave work to get you a cigarette because you’re crying.”

(in italics) “Are you going to bury someone? Or dig someone up?”

What do we notice? The story is well and truly kicked off. Not only do we have plot and character and point of view, but we also have some stakes built into the story. Now, it can be hard to have MASSIVE stakes present in the first sentence, but Mr. Keaton lets you know that SOMETHING COOL WILL HAPPEN and THE EVENTS MEAN SOMETHING TO THE CHARACTERS, SO THEY SHOULD MEAN SOMETHING TO YOU.

Compare to…hmm…what books do I have in front of me:

Aubrey Hirsch’s “Theodore Roosevelt:” “Teddy Roosevelt is almost certain that his daughter, Lee, is a lesbian.” (CHARACTER, POV, PLOT, STAKES)

Elmore Leonard’s “How Carlos Webster Changed His Name to Carl and Became a Famous Oklahoma Lawman:” “Carlos Webster was fifteen years old the time he witnessed the robbery and murder at Deering’s drugstore. (CHARACTER, POV, PLOT, STAKES)

Lee K. Abbott’s “Dreams of Distant Lives:” “The other victim the summer my wife left me was my dreamlife, which, like a mirage, dried up completely the closer we came to the absolute end of us.” (CHARACTER, POV, PLOT, STAKES)

I think these examples are even more potent than the ones I discussed in one of my GWS Videos:

The point is that good things often happen when you supercharge your first sentence and make sure that it contains:

Mr. Keaton is particularly good at creating really cool images. For example:

Only a guilty man soaks up enough electricity to power a city block, pulling fishhook after fishhook of Taser wire from his torso, all while cuffing any cop that got too close with fists half the size of Thanksgiving turkeys.

[He’s describing clams.] At first, they’d just be foam trails off the tips of something almost invisible. But when I’d lean down on my elbows, I’d see they were actually creatures that moved like anything else moved when it was exposed. They tried to hide. Looking close, I could see them desperately digging to bury themselves before the next wave. Their time, jelly-like tongues would roll out like party favors, start twitching and shoveling, and then, impossibly, balance the entire structure on one end, then pull themselves down, down and gone.

So how do we pump up our writing with cool images?

I’m not sure if I’ve ever done this before, but let’s put a writer who is worse than Mr. Keaton to THE GWS TEST. Today, we’ll look at the work of a crummy writer and see if his stuff can be improved with this advice.

Our contestant today is…me. Let’s see. One of the stories I’m shopping around is called “Masher Doyle.” Let’s check out the first sentence:

Masher Doyle came into my life at the time I most needed him.

There is a hint about the protagonist…good, good…the first person POV is established…the plot certainly revolves around the relationship between the narrator and Masher Doyle…and there are emotional stakes; the narrator is describing a time that was bad for him. Okay. Not quite Mr. Keaton-worthy, but good enough. Let’s look at one of the crummy images in my story and see if we can’t make it better.

Okay, here’s one:

When my mother sent me to the corner store for milk, she slipped me an extra forty cents so I could buy a pack of baseball cards. Before heading home, I would sit on the curb and slip my dirty thumbnail under the flap, pull it, then flip through my new cards.

What would Mr. Keaton do? He would use powerful verbs and powerful adjectives. Do I? “slipped, extra, buy, sit, slip, dirty, pull, new…” I dunno. Those aren’t the most energetic words around.

Here’s another bit from Mr. Keaton:

It reminded him of a Halloween pumpkin he forgot to carve once as a kid, when he just drew eyes, nose, and a mouth with a black Magic Marker and then forgot about it until New Year’s. When he picked it up, his thumb sunk into its eye as easy as he imagined a real eye would accept its fate, and it collapsed around his grip in a gush of rotten orange and black.

Yeah, see? We all need to use verbs and adjectives that crackle with energy.

What Should We Steal?

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

David James Keaton is a very interesting fellow. The gentleman is very prolific and seems very cool. He loves music and crime fiction…but I’m not sure he’s such a big fan of authority figures. His aversion to them is fine by me, as it resulted in the stories presented in Fish Bites Cop! Stories to Bash Authories, a book you should certainly get into your hands and heart. Here is the entertaining manner in which Mr. Keaton explains how you can order the collection:

If you’re looking to buy it (did I already post these retailers somewhere? oh, well), here’s a link to the Comet Press website, as well as links to Barnes & Noble (for locals), Carmichael’s Bookstore (for locals), Powell’s, Indiebound, and Amazon. I listed those in order of preference. Buy it from the publisher or the real stores first, unless you need it on Kindle. Who knows where that Amazon money goes.

Ordering Mr. Keaton’s first novel is a little easier; Broken River Books has made signed hardcover copies of The Last Projector available through their web site. The book will be worth a look; one of the things I wondered while reading Fish Bites Cop! was what Mr. Keaton would do when he had a vast canvas at his disposal instead of many small ones.

Sure, you might want to know about how Mr. Keaton articulates his overall philosophy regarding fiction. You may want to read a 10,000-word essay in which he writes in great detail what makes a story interesting to him. Well, look elsewhere for those things. I’m really curious about some of the small choices that shaped the stories of Fish Bites Cop!

1) Okay, so I made a chart of Fish Bites Cop!’s table of contents as a public service. (You can never find a simple table of contents for story collections!) I also did it so I could look at stuff a little analytically.

| Title | POV | Number of Pages |

| Trophies | 3rd | 2 |

| Bad Hand Acting | 3rd | 8 |

| Killing Coaches | 1st | 8 |

| Schrödinger’s Rat | 1st (we) | 13 |

| Life Expectancy In A Trunk (Depends on Traffic) | 1st | 8 |

| Greenhorns | 3rd | 12 |

| Shock Collar | 3rd | 4 |

| Third Bridesmaid From The Right (or Don’t Feed The Shadow Animals) | 1st | 11 |

| Burning Down DJs | 1st | 6 |

| Shades | 3rd | 6 |

| Three Ways Without Water (or The Day Roadkill, Drunk Driving, And The Electric Chair Were Invented) | 3rd | 11 |

| Heck | 3rd | 4 |

| Do The Münster Mash | 3rd | 4 |

| Either Way It Ends With A Shovel | 3rd | 14 |

| Castrating Firemen | 1st (directed at silent interlocutor) | 5 |

| Friction Ridge (or Beguiling The Bard In Three Acts) | Play | 14 |

| Doppelgänger Radar | 3rd | 4 |

| Queen Excluder | 3rd | 12 |

| Don’t Waste It Whistling (or Could Shoulda Woulda) | 1st (directed at silent interlocutor) | 3 |

| Three Minutes | 3rd | 3 |

| Bait Car Bruise | 1st | 3 |

| Clam Digger | 1st | 8 |

| Swatter | 1st | 8 |

| Three Abortions And A Miscarriage (A Fun “What If?”) | 3rd | 14 |

| Catching Bubble | 3rd | 3 |

| Doing Everything But Actually Doing It | 3rd | 9 |

| The Living Shit (or Mosquito Bites) | 1st | 6 |

| Warning Signs | 3rd | 3 |

| The Ball Pit (or Children Under 5 Eat Free!) | 3rd | 6 |

| Nine Cops Killed For A Goldfish Cracker | 3rd | 22 |

There are 30 stories in the book.

The longest story is 22 pages.

9 of 30 are longer than ten pages.

10 of 30 are between six and ten pages.

11 are under five pages.

How come the stories are so short? Are you influenced by the Internet-inspired growth of the popularity of short-shorts? The stories are very “idea-oriented”…are you consciously trying to get the idea out of there as quickly as possible? Your prose is fun and punchy; do you feel you need to accentuate that part of your writer’s toolbox?

DJK: Interesting! These statistics are new to me. Did you like the scary fish picture on the contents page? I like that fish. That’s what I imagine goldfish crackers look like in our bellies. Well, as far as length, a couple venues that I was submitting to did dictate length. For example, “Warning Signs” went to Shotgun Honey, which had a 700-word limit, an odd but challenging (and kinda arbitrary) number. Also, many of these shorter pieces were written when I had zero publications to my name and I thought I could somehow crack that elusive code by writing tiny flash pieces and “get my name out there.” Translation: Give fiction away for free! Instead, this mostly meant getting Word Riot rejections five or six times a day (fastest rejections ever!). And this might be kind of a boring answer, but most of the stories are as long as they wanted to be. Well, a more boring answer would actually be “as long as they need to be.” But, truthfully, some of them probably needed to be shorter. But it’s not about what they need. It’s what we need, right?

2) A lot of us have real trouble figuring out character names. Many of your protagonists are named “Jack” or “Rick.” Why do you do that for? Are you making a point about how everyone is kinda the same, regardless of names? Or do you just like that the names are short and easy to type?

DJK: You mentioned to me in an earlier conversation how Woody Allen claimed he used names like “Jack” because they are so much more efficient, and I’m totally on board with this reasoning. It’s like Jeff Goldblum in The Fly and his closet is full of the same shirts and pants and jackets – because this means he doesn’t have to expend any brainpower on unimportant things. Although, to be fair, Goldblum’s character does all his best thinking once his girlfriend buys him his first very ‘80s bomber jacket. But for me, naming a character “Jack” is also like a shortcut to not having to name someone at all. “Jack” feels like a not-name to me, not as obviously anonymous as “John,” and it sort of sounds like a verb, too, so that’s a bonus. I’m just not that interested in names. I also don’t enjoy describing characters. Not sure where the aversion comes from, but I’d number little stick figures if I could!

Also, whenever there’s a “Jack” who is a paramedic, that’s actually a tiny snippet of my upcoming novel The Last Projector. In that book, there’s just the one Jack. Well, he’s kind of a couple people, too, but that’s another story. But in Fish Bites Cop!, the Jacks are different people, unless they’re paramedics. If that makes any sense. This answer has gotten so long and thought-consuming that I’ve now reconsidered and may start using normal names again.

3) “Nine Cops Killed For A Goldfish Cracker” is a really cool story. And you do a cool thing in it. There are three big countdowns that control the progression of the story.

How did you make use of these countdowns in your story? How did you make sure that the “mileposts” passed quickly, but not too quickly? How did you make the countdowns seem organic instead of all contrived and stuff?

DJK: Thanks! The countdown that shaped the story the most was the deaths of the titular “nine” cops (ten, actually). By thinking of creative ways to murder them, it gave me a very convenient way to map it all out. The countdown of the dying fish was a heavy-handed parallel to the dying cops, so that countdown was supposed to be like a Star Trek mirror-universe version of what the drying fish and dying cops were going through. The yard-line countdown was added in the 11th-hour of writing, to smooth it out and to accelerate things a bit more. Once I added yard lines, the rest of the football imagery started popping up organically and things really got fun. But the deaths of the police officers were definitely the story’s engine, and not just because I knew that a reader would expect exactly nine police officer deaths as promised, and I knew I had to deliver. But it drove the story because, when I wrote it, I’d been working late hours at my former closed-captioning job, and we had short, unhealthy lunches built into our demanding captioning duties, so that countdown was also a way to get a little bit of the story done each night on my 15-minute lunch break. One little murder a day, I’d tell myself, and I’d be home free in a week! How many times have we said that to ourselves?

4) Several of the stories have alternate titles. (For example, “The Living Shit (or Mosquito Bites)”). Coming up with titles is hard for a lot of us. Why did you include some alternate titles?

Some of the titles are really descriptive and reflect what happens in the story (“Killing Coaches”) and some are a little more “fun.” What do you think is the relationship between the title and the story?

DJK: Most of the alternate titles in the collection are their original titles. “The Living Shit,” for example, was renamed “Mosquito Bites” to make it more palatable and get it published. But I always preferred the uglier title, so I switched it back. In fact, the original title of “Nine Cops Killed for a Goldfish Cracker” was “Fish Bites Cop.” But instead of adding an alternate to that already very long title, I just called the collection Fish Bites Cop instead. Problem solved! That meant the newspaper headline at the end of the story is also swapped around. Now the newspaper reads, “Fish Bites Cop!” too. Which I kind of prefer, actually. And hijacking that story title to make it the title of the book suited the collection in many unexpected ways.

But, yeah, some of the “fun” titles were titles I had kicking around that I really wanted to write a story around. Like “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel” was actually an email subject line that my friend Amanda and I passed back and forth at that captioning job whenever we were disgruntled. So that title was her idea actually. To write a story around it, I just had to think of the two “ways” that would go with it. And the question of burying someone or digging them up seemed to be the only option.

5) “Greenhorns” and “Clam Digger” are two of my favorite stories in the book. They’re also a little different from the other stories, as they feature fantasy/supernatural elements.

How come there are only a few horror-y stories in the book? The rest seem extremely hard-boiled and realistic. (Even though the stories feature “extreme” events, of course.)

DJK: When I wrote most of these stories, I was in grad school at the University of Pittsburgh, and many were sort of an affectionate raspberry to the typical MFA-style “lit” story. So I was purposefully playing with every genre I could. The fact that the vast majority also incorporated authority bashing of some kind is a mystery for a psychologist to unravel. Hopefully, a psychologist who is just starting out so that he or she is real hungry and really, really wants to get to the bottom of these things. Or maybe a recently martyred movie psychologist who will absolve me with four magic words, “It’s not your fault.”

6) You’re real good at using unexpected verbs.

In “Bad Hand Acting,” the janitor doesn’t “walk around” the mob of police. He “orbits” them.

In “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel,” the character doesn’t just “look at” or “see” a bunch of bodies in his car trunk. He “studies” the bodies and “counts” the “elbows and knees as tangled as his guts.”

In “Shades,” the narrator “drops” a dollar in a peddler’s hand, which is a lot less secure than “handing” a bill to a person.

How do you know when to use a regular old boring verb and when to use a cool, unexpected one?

DJK: Back in school, I was told verbs are very important to bringing a scene to life and their power shouldn’t be squandered through use of lazy words like, “are” and “to be,” like I just did in this sentence.

7) One of the things I really like about the stories is that you include a lot of fun “extra” stuff in your work. “Clam Diggers” is very much a story about a man relating how his brother disappeared. Still, you manage to sprinkle in a cool image/story about how the father taught the sons to turn bathroom graffiti swastikas into “neutered” sets of boxes. Unfortunately, writers like me have led sheltered, boring lives, depriving us of the opportunity to come across these kinds of interesting anecdotes and ideas. How many of these cool things in the stories come from your real life? Should sheltered writers like me just allow myself to make up stuff? I’ve obviously never planned an inside job scam on a casino…should I just stop restricting myself and assuming I couldn’t write such a story?

DJK: Neutering swastikas into tiny four-paned windows is a favorite pastime of mine, as I found that moving to Kentucky means more than the usual quota of bathroom-stall neo-Nazi graffiti. See this is where the revolution will begin… on the toilet! And many of the digressions, er, details do come from my day-to-day or past adventures. I did win and lose and win back about three grand at roulette, and I committed all those ridiculous infractions at the roulette wheel at the MGM Grand Casino in Las Vegas. I’d like to say that was research, but it was my friend’s crazy wedding. I didn’t try to scam them, of course. All the flavor that my personal experience can bring to the stories stops just short of the actual crimes. Except for one. Maybe. Sort of. Next question!

8) You REALLY like to start stories with the inciting incident or with a sentence that represents the overarching feeling of the piece or its narrative thrust. See?

Shades: “She was sure one of them was watching her.”

Burning Down DJs: “Before the night ends with me crashing through the woods in a stolen police car, I’ll drive around stuck on one thought.”

Queen Excluder: “There were sitting down to dinner when the phone rang.”

Castrating Firemen: “I will leave work to get you a cigarette because you’re crying.”

Either Way It Ends With A Shovel: (in italics) “Are you going to bury someone? Or dig someone up?”

How much of this is planning and how much comes in the second draft? Are you only doing it because most of these are crime-related stories and plot is really important?

DJK: Those examples were part of the original drafts. I’ve always been a fan of getting things going in the first sentence, to engage both the reader and the writer. And because I can’t wait to get the main idea out, front and center (like the “Are you going to bury someone or dig them up?” question in “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel”) and because I trust myself a little more with the plot rather than the prose. At least until the story gets cooking.

9) So I think I understand why you have thirty stories about authority figures (police officers, firemen, paramedics). It’s probably the same reason I have 150 stories about ugly dudes whose flawed natures has resulted in the fact that none of them have ever had a healthy relationship with a woman. These are topics of particular and personal interest to us, so we’re going to write about them.

What I wanna know is how you figured out the order for all of the stories. (We’re all hoping to have the same assignment someday!) How come the super-long award-winning story was last instead of first? How come the shortest story was first? What kind of experience were you trying to shape for the reader?

DJK: When it turned out I’d accumulated thirty stories that punished police officers, firemen, paramedics, high school coaches, etc., I was kind of surprised. It really wasn’t a conscious effort. Well, there were probably about twenty stories stockpiled with this similar theme before I realized the connection, and then I wrote ten more because I felt like I was on a roll and wanted to get it all out.

It’s still not all out though. A beta reader is going through my novel, The Last Projector, right now, and for kicks he counted up the total uses of the word “cop,” “officer,” and “police.” You might enjoy this with your statistics fetish earlier!

In 500 pages, there are around 700 uses of these terms. Second most used is the word “fuck” with 600. And most of those “fucks” and “cops” are probably pretty closely intertwined. And this is not a novel about police officers. So I guess it’s out of my hands.

As far as the order of the stories, that was sort of complicated:

“Nine Cops Killed…” wraps up the book because it’s the title story, and I feel like it’s a big party, a fun bash where the reader can be rewarded for making it through the whole thing. And the shortest story starts things because “Trophies” felt like a mission statement to me. It had a lot of the elements that are consistent throughout, regardless of the genre hopping.

But as far as the order of the stories, I spend a loooooooong time on that. I definitely “mix-taped” it High Fidelity style. The first “song” starts off fast, then the next song kicks it up a notch. Then the next song slows things down a notch, etc. etc. And I also wanted stories that were first-person to avoid following each other, lest people think those “Jacks” were the same Jack, of course. And I wanted the genres to be spread out, so that people didn’t expect a third monster movie after a monster double feature. And after all that work of mix-taping, I read an article on HTML Giant that declared very definitively that, “Short Story Collections Are Not A Mix Tape!” and then I was satisfied that I had done the right thing.

10) Look at the last few pages of “Clam Digger.” This cool story is told by a first-person narrator who is relating events that happened a long time ago. He therefore has access to a lot more information than the younger version of himself.

So the narrator lets us know this is THE STORY OF HOW HIS BROTHER DISAPPEARED AND YOU CAN BELIEVE HIM OR NOT; HE KNOWS WHAT HE SAW. (We’re also informed he’s participating in some kind of interview.)

So the bulk of the story finds the narrator telling the story in the past tense, chronologically jumping from one significant event to the next.

But check out the end of the story. We’re getting the “money shot,” so to speak. The mystery of the brother’s disappearance is being revealed…

Then you cut to a new section, leaping from the past to the present to the past again. Why did you break the pattern established by the rest of the sections? What was the effect you were trying to create? Are you willing to apologize for my newfound fear of clams and other mollusks?

DJK: I guess that was an attempt to build suspense, sort of use those Sam Peckinpah directorial editing tips where you cut away right when the shot has peaked. I also maybe stutter-stepped there at the end because I wasn’t sure how I was going to wrap it up. The natural ending of that story felt like it should be in the past, since that’s where the mystery was, but there had to be resolution in the present, too. So I tried to do both, at the risk of the dog in Aesop’s fable who growls at his reflection in the water and loses both bones.

“Clam Digger” was also my first run at a “Lovecraftian” story. So I had some tortured soul spinning some yarn about the horribleness he’d witnessed, some large ocean-dwelling critter that may have driven him insane. But other genres started to cross-fertilize while I was writing it, and the story that resulted is really more psychological horror than anything.

I do apologize for your new clam and mollusk aversion, though. But it’s better than an aversion to naming characters, so you should be thankful! And it’s only fair this happened to you because those things freak me out, too. I mean, look at clams for a second, if you have one handy. You think it’s sticking its tongue out at you, but it’s a foot? You think it’s sticking its eyes out at you, but that’s its nose? That’s insanity on the half shell right there.

David James Keaton’s award-winning fiction has appeared in over 50 publications. His first collection, Fish Bites Cop: Stories to Bash Authorities, was named This Is Horror’s Short Story Collection of the Year and was a finalist for Killer Nashville’s Silver Falchion Award. His debut novel, The Last Projector, is due out this Halloween through Broken River Books.

2014, Comet Press, David James Keaton, FISH BITES COP!, Why'd You Do That?

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Aaron Burch may best be known as the editor of Hobart: another literary journal, but we mustn’t forget that he’s a great writer in his own right. Backswing, released by Queen’s Ferry Press, is Mr. Burch’s first short story collection. If you haven’t already done so, why not order a copy of his book from the publisher?

Sure, you might want to know about how Mr. Burch articulates his overall philosophy regarding fiction. You may want to read a 10,000-word essay in which he writes in great detail what makes a story interesting to him. Well, look elsewhere for those things. I’m really curious about some of the small choices Mr. Burch made while writing and putting Backswing together.

1) Here are some of the sentences from Backswing:

“She calls Roy, says: I have a new trick.”

“We built a fence around the remains, left it as it was in case he should return.”

“We elected Mo as recorder, made him repeat back to us, sometimes, the moments that seemed most important or confusing…”

You seem to like this sentence structure where you start with the subject of the sentence, pop in a comma and then omit the conjunction before the next verb. What’s up with that? What is the effect you’re trying to create?

AB: I do, I like that sentence structure a lot. I like the way it looks on the page, the way it sounds, the way it almost feels a little off, grabs or startles your attention a bit. I’m trying to think of where it came from, and I’ve got a few ideas. One is that it grew out of writing short-shorts: trying to make every word count; trying to cut words to, say, get down under Quick Fiction‘s 500 word limit; and also probably from Coop Renner at elimae‘s having edited pieces and showing me how I could play with language and sentence structure. The other thing that jumps to mind, and this is kinda a perfect first question/answer for “great writers steal,” is how influential Sam Lipsyte is. Venus Drive is one of those collections I go back to, over and over, probably as frequently as the nearly universally heralded Jesus’ Son. Maybe my favorite sentence (or, I guess two sentences) of all time are from “Old Soul”:

Somebody told me they were exploited. Me, I always paid in full.

I don’t know, I think the way that second sentence turns is perfect. Rereading, it’s doing something a little different than the examples you point out above, but there’s something about the comma as hingepoint for a sentence that I feel is really interesting, and I’ve probably been emulating that Lipsyte move for years. Though now, of course, I never think about it when writing, I think I just like the sound of it.

2) My story of mine that I kinda like the best has the narrator performing magic tricks. It’s really really hard to write magic tricks in fiction because the writer must conceal things the narrator knows from the audience in the story and the reader. But we can’t hide too many things or our reader won’t understand what’s happening. Your story “Prestidigitation” features a magic trick interspersed with exposition.

How’d you keep the magic clear to the reader? What were you thinking when you tried to describe something inherently visual in words?

AB: Again (and I’ll try not to add this disclaimer to every answer, we can just assume it applies across the board?), a lot of what makes it work (or, I hope it works, at least) is me playing with the story while writing it but not thinking this explicitly about what is and isn’t working, but just progressing by what feels right. Looking back now though, I think the tense and POV is pretty important here. It’s in 3rd person, but much “closer” to Roy, and is present tense, so we’re seeing Linda’s magic trick at the same time as Roy is — they’re a couple and so he knows some of the behind-the-scenes of her magic, but this is a new trick so he doesn’t know what she is going to do until she does it, so that’s where we are, too. He’s not sure what is going to happen next, but he’s curious, and he’s not just wondering what will come next but is at the same time trying to figure out how she’s doing what she’s doing. That feels like a good place for us, the readers, to be in, yeah?

That said, I did think about describing everything enough so that we could see it as much as possible. Going back, making sure where each of her hands are, what they’re doing, all of that, is as descriptive as possible so that we could follow along.

3) “Church Van” is a real cool story. There are two Roman-numeraled sections in the piece. The first one is a third person POV limited to Densmore, the protagonist. The second one is a first person POV whose narrator focuses on the reaction of the group trying to understand what Densmore was up to.

We’ve all been told a jillion times not to switch POV, but breaking that rule works in “Church Van.” Why does it work? Is it just the numbered sections? How come you didn’t just use a third person omniscient POV in the whole story?

I really think of the story as in two parts. (Though I can’t remember at what point during writing it this happened, if that was kind of always there or if it grew into that. Probably the latter, actually.) I think the story started with that first half, the idea of this dude eating a car. To again play into the idea of “great writers steal” (and also maybe over-admitting influences?), that germ of the story was more or less stolen from Harry Crews’s short novel, Car. Only, I’d heard of the book but hadn’t yet read it, and so kind of wanted to try to write a “response” to something I hadn’t actually read, see how much/effectively I could turn it into my own thing. Then, like a number of the stories in the book that are playing with more Biblical ideas, it turned into me wanting to play with the mythology of it all. I liked the idea of trying to set something up that was both the “origin story” and then the myth that it got turned into. I think the way that works, in this story, is the juxtaposition of those two sections and POVs. I actually remember workshopping this story and some comments that it might (would?) work better if the two halves were threaded together, which I guess feels more traditional, but I really like the jarringness of it this way, of how one works with and against and in response to the other.

4) “Fire in the Sky” rocks. It’s about a group of friends sharing a last night of stupid fun before one of them gets married. Something real bad happens to the groom-to-be in the story’s explosive climax. The narrator and Jeff head out on their own while things get sorted out.

I kept thinking that you were gonna have Jeff and the narrator come back to the groom-to-be. Why’d you end the story away from Hank?

AB: Again, and maybe even more than any of these other questions: intuitively. It’s actually maybe a bit more of a “short-story-y” ending in my mind than I typically like, ending with them just running, but it felt right. I don’t think I ever even considered having them return. I guess, if this were a chapter or piece of something larger, they’d have to and the story would then deal with the ramifications of what had happened, but as-is, they are just purely in the moment, which feels a nice way to end things.

5) People like me don’t have a short story collection, but we really want to publish one one day. The stories in Backswing have a mixture of POVs. It seems like an even split, give or take, between first and third with a second person story thrown in there.

Did you have this kind of variety on your mind when you put all of the stories together and put them in order? The book starts with a story about a guy who is forced to deal with his problems and ends with a story who seems to be heading out on a new adventure, leaving an old life behind. Did you do do this on purpose?

AB: Yeah, this was probably the aspect of the book I did think the most about. I really wanted it to feel like a book, not “just a collection” (as Kyle Minor says in his new Praying Drunk, albeit in a completely different way), but I also really wanted it to have a good variety. Which is maybe wanting to have it both ways, but I felt like it was possible.

When I was writing the stories individually, I want to say something super “writer-y” like I just wanted to find the POV and tense that best fit the story being told, but the reality is probably more that I was often giving myself these small challenges to try to keep from repeating myself. So…how would this story work in first person plural, etc.? And then there’d probably be a push and pull between one being adapted for and influencing the other, and vice versa, such that each hopefully did push toward using those kinds of aspects of itself toward its best benefit.

So, that’s why I had a variety of stories and, like I said, I wanted to try to find the best of way putting them together and presenting them. Which meant trying to find the “best” order for the book, and also cutting stories that maybe felt too similar and didn’t bring anything especially new to the whole, even if they were strong on their own, and that kind of thing. And also having friends read it and give input.

6) During my MFA, my awesome teachers (Lee K. Abbott in particular) advised me to use pop culture references in a smarter manner. They’re real smart and I have indeed cooled it a great deal. Sometimes, however, we just hafta use pop culture references. You start “Flesh & Blood” with a reference to Bret Michaels’ eyes and invoke “Unskinny Bop.” You mention Wall Street and Glengarry Glen Ross in the book. You mention Corvair Racers.

How do you decide when a pop culture reference should stay? What do you hope a reader who was born in 1997 thinks about the references?

AB: I probably overuse pop culture references, so I maybe could have used a teacher that told me that, actually. I find myself, in conversation but also just to myself when thinking of things, making a lot of comparisons to movies, especially, and so I find myself doing that in my stories, too. I think, too often, they’re probably used either as short cuts or just because they’re fun, so I guess the trick is to try to make them purposeful. I often drop the in to show that they are how my characters are connecting to the world, not just me, the author. As far as connecting to different generations… I guess you hope that the writing around the references is good and clear enough such that if someone hasn’t seen the “Unskinny Bop” music video, they still get what you mean and they’re not at a loss, and if someone has, it’s a bonus.

7) I am always thinking about when writers omit question marks. It’s controversial to some, but it’s a valid technique writers can employ to shape the reader’s experience.

Why’d you omit the question marks in stories like “Prestidigitation,” but you did use them in stories like “Unzipped”?

AB: Like saying I would push myself to use different POVs, I think at times it was a challenge (how to make it make sense that this story doesn’t have them, whereas this other one does?); and like me repeatedly calling out the very name of this website, it was at other times probably just because I was reading authors that didn’t use them.

Probably, mostly, it was intuitive. I think that intuition, for myself, meant using them for the more traditional “realism” stories (like “Unzipped,” “Scout,” etc.) and omitting them for the stories that felt a little more… I don’t know what you want to call them. “Experimental” isn’t quite what I mean.

8) Writers are also always thinking about how to use white space. And why to use it. And when. If you look at the middle of “Fire in the Sky” (page 87), you have your characters standing around in tuxedos and watching fireworks light up the sky. Then you have some white space before “Todd dropped a mortar into the tube.”

It doesn’t seem like much time has passed. It seems like the white space is optional and you could just have kept those two paragraphs together. How come you put white space there?

AB: I think there’s a couple things going on here. The first is that I think more time has passed than it maybe seems. They’re standing around in tuxes, watching fireworks at the beginning of the night, and then white space, and then the end of that “Todd dropped the mortar…” sentence is “…same as we’d been doing all night.” So there’s been a night’s worth of this already, during that white space break.

The second is that I try to use section breaks as not just signifiers of time having passed but as…well…just that. A “section break.” Meaning I want each piece in between those white spaces to work as its own section, almost maybe like a short-short, even, if I want to tie it back up to that first answer.

9) “Flesh & Blood” begins with two paragraphs about the teenage protagonist (Ben) noticing his burgeoning sexuality through the lens of what he sees on 1980s-era MTV.

My question is this: why do they still call it MTV when there’s no M on the TV?

Just kidding. After the reader is reminded about the thinly veiled expressions of sexuality in early music videos, you use a section break and write, “All summer, Ben has kept to his new bedroom as much as he can get away with.” That sentence introduces the protagonists, hints that he’s undergone some kind of big personal change and sets up the beginning of the school year-a transition that kicks off the narrative. In other words, it’s a rockin’ first sentence.

How come you began the story with the MTV stuff instead of the next section that really kicks off the events Ben goes through?

AB: AGAIN, like most of this, I hadn’t actually thought about this until now, but I’ve been thinking about it a lot, in how to reply. I can really only say that, for me, introducing MTV always felt like the beginning of the story. (Actually, even more specifically, it was first written with each piece of the narrative interspersed with a detailed description of that “Unskinny Bop” video, with the description of Bobby Dall’s Corvair Racer, etc. Which was super helpful for me, while writing the story, but then ultimately didn’t work. But I still wanted to open on the video.

I also think, you’re right, that second section is maybe a more traditional story opening, and does a lot of what you’re supposed to do to introduce a story. And maybe starting with MTV is not technically the best opening and over-relies on the aforementioned pop culture references, but I think that song and video are also exactly the “transition” you mention that is basically what the narrative is about, Ben’s “noticing his burgeoning sexuality,” all that. That video was 1990 and Poison was all over MTV, but within the year, “Smells Like Teen Spirit” had appeared, making Poison just about the furthest thing from cool.

Also, and maybe most importantly, starting with Bret Michaels just seemed more fun.

10) I’ve noticed that a lot of the stories in Backswing are about men who are dealing with grief in different ways, many of which aren’t necessarily healthy.

As a successful writer with a (soon-to-be) published collection of short stories, what do you think when some random weirdo tells you what he thinks your writing is about?

AB: You know… it seems kinda awesome. I think it’s often hard to know what your own stories are about, or even to see some of your own tendencies or common themes or to try to summarize your own writing. I think “about men who are dealing with grief in different ways, many of which aren’t necessarily healthy” is probably just about a better way of super briefly summarizing the connections of the stories than I could do, plus it’s obvious from the above questions that you actually spent some time with the book, and so that’s kinda exactly what you’re hoping for, I think.

Aaron Burch is the editor of HOBART: another literary journal, and the author of the novella, How to Predict the Weather, and How to Take Yourself Apart, How to Make Yourself Anew, the winner of PANK’s First Chapbook Competition. Recent stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Barrelhouse, New York Tyrant, Unsaid, elimae and others.

2014, Aaron Burch, Backswing, Queen's Ferry Press, Why'd You Do That?

Title of Work and its Form: Backswing, short story collection

Author: Aaron Burch (on Twitter @Aaron__Burch)

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: Backswing can be purchased from Queen’s Ferry Press. Click here.

Bonuses: Mr. Burch is very much a successful writer in his own right, but he is also notable for what he has done as editor of Hobart: another literary journal. Here is a story that Mr. Burch published in Storyglossia. Why not check out How to Predict the Weather, one of Mr. Burch’s previous books?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Mythological Underpinnings

Discussion:

Backswing is a cool collection of stories written by a cool storyteller. There are fourteen stories in the book and each of them has their own unique charm. It can sometimes be hard to find a table of contents for story collections, so I have compiled one for you:

|

Story Title |

POV |

| Scout | 1st |

| The Stain | 1st (“we”) |

| Prestidigitation | 3rd |

| Flesh & Blood | 3rd |

| Fire in the Sky | 1st |

| Sacrifice | 3rd |

| Unzipped | 3rd |

| The Apartment | 1st |

| Fair & Square | 2nd |

| Night Terrors | 1st |

| Church Van | 3rd…then 1st (“we”) |

| The Neighbor | 3rd |

| After the Leaving | 1st (“we”) |

| Train Time |

1st |

One thing that you’ll notice about Mr. Burch’s work is that he often enjoys referring to and playing with mythology. “After the Leaving” is a retelling of the Noah’s Ark story and Cain and Abel play a big role in “Sacrifice.” What does Mr. Burch gain by making explicit use of Christian mythology?

More importantly, Mr. Burch creates his own parables. “Church Van” is an interesting story about a man who is coping with the death of his father. Densmore deals with the loss in an unexpected and thematically appropriate manner: he buys the titular van, a vehicle that had witnessed some of his best childhood memories. Sounds normal enough, right? Well, Densmore begins to eat the van, piece by piece. The turn is accompanied by a POV shift; the narrator exists first alongside Densmore before moving to present the thoughts of the public witnesses to Densmore’s strange act of self-flagellation.

So if you distill the story to its basic elements, “Church Van” is really just a depiction of the power of repentance, a near-universal concept. Star Wars is a depiction of the battle between good and evil and the struggle we all have to escape the sins planted in us by our parents. Harry Potter is a depiction of the battle between good and evil and the struggle we all have to understand our own destinies. The Lord of the Rings is a depiction of the battle between good and evil and the struggle we all have to control our greed. Wall Street is a depiction of the battle between good and evil and the struggle we all have to control our own greed.

Gee, it’s almost as if these big stories are all pretty much the same and that you can produce something powerful if you think of your work in terms of mythology.

The stories in Backswing have thematic similarities, but Mr. Burch can’t be accused of telling the same story a dozen times. Not only does he mix up points of view, but he experiments with a wide range of settings, from the fantastic to the familiar. Perhaps my favorite story in the collection is “Prestidigitation,” a story that I happened to read when it premiered in Barrelhouse. The female protagonist of the story performs a magic trick for her boyfriend, creating a temporary alternate reality. (Isn’t that what magic tricks do?) Compare that story to “Train Time,” a first-person story in which the narrator is creating his own fantasy around the woman who sits beside him on a train. Mr. Burch also experiments with form a great deal.

“Flesh & Blood” and “Fire in the Sky” and “Scout” are “normal,” “traditional” stories. What do I mean by “traditional?” The characters are fairly “normal.” They certainly do interesting things in their stories, but there’s nothing “experimental” or “challenging” about stories populated by suburban males who enjoy golfing, pick up skateboarding or attend a bachelor party. I’m certainly not saying that there’s a negative to setting your stories in situations to which many of your readers can relate. (We all spend time with friends. We’ve all been the “new kid” in some way.) What I’m pointing out is that Mr. Burch complements these narratives with far “stranger” ones. “The Stain” is odd and cool and doesn’t take place in a world we recognize. “The Apartment” has a distinct Twilight Zone flavor.

I suppose what I’m urging us all to do is to experiment a little bit. For example, I so liked the conceit of the Aubrey Hirsch piece I wrote about that I am “experimenting” with a piece in a similar vein. While I can be frustrated by writing that is ALL experimentation, why shouldn’t we push our boundaries a little in the way that Mr. Burch does. Some stories deserve to be told in a “normal,” “traditional” way and some require us to challenge the reader a little bit with form. (Mr. Burch, of course, never leaves the audience behind when he tries something different, and neither should you.)

Here’s an interesting corollary lesson. “The Stain” and “After the Leaving” are two of the more “experimental” stories in the volume. Both are written in the first person, but the protagonist is “we.” “Us.” One of the reasons that the stories aren’t difficult to hang with is that WE are instantly aligned with the narrator by virtue of being included.

Mr. Burch’s first short story collection deserves a lot of attention because the stories are satisfying and the value of the whole is greater than that of its parts. Writers would do well to pick up a copy because Mr. Burch’s endless imagination and solid use of craft can help them improve their own work.

What Should We Steal?

2014, Aaron Burch, Backswing, Barrelhouse, Hobart, Mythological Underpinnings, Queen's Ferry Press