Title of Work and its Form: “”In the style of Joan Mitchell”,” poem

Author: Janelle DolRayne

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem debuted in the October 2014 issue of inter | rupture. You can find it here.

Bonuses: Here is an apt poem that was subsequently chosen for Best of the Net 2013. Here is a reading list that Ms. DolRayne put together in her capacity as Assistant Art Director for Ohio State’s The Journal. Want to see the poet read her work?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Conceits

Discussion:

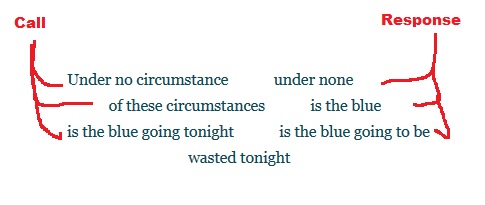

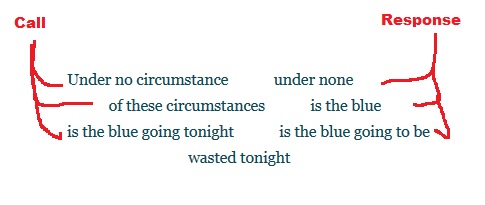

Ms. DolRayne offers us a poem with a fun and interesting conceit. (It bears mentioning that Ms. DolRayne may not have the same idea as I do about her poem…but that’s okay.) It seemed to me that the poem is a powerful attempt to use poetry to mimic the loose and quietly powerful feel of a folk song. If you’ll notice, the first few stanzas feature lines that employ the call-and-response technique popular in folk, blues and rock music:

You’ll also notice that the last stanza abandons the conceit, which is perfectly fitting. The narrator of the poem is now speaking in “unison” or “a cappella.”

You’ll also notice that the last stanza abandons the conceit, which is perfectly fitting. The narrator of the poem is now speaking in “unison” or “a cappella.”

First, I’ll give you some examples of the call and response I’m talking about. Phil Medley and Bert Berns wrote “Twist and Shout,” a song that was covered by a lot of groups, including The Beatles. You’ll notice that the background vocalists mirror and augment the lead singer.

Steven Page and Ed Robertson wrote “If I Had a Million Dollars.” As I understand it, Ed had written the bulk of the song, but only had his part of the vocal. Mr. Page heard the song in progress and added his part. Mr. Page sometimes simply repeats Mr. Robertson’s part; sometimes he adds to the narrative of the song and takes it in a new direction.

The response doesn’t even have to come from a vocalist. In George Thoroughgood’s “Bad to the Bone,” the response comes from guitar and saxophone.

I loved Ms. DolRayne’s use of this technique for a number of reasons:

- Poetry is just a kind of music, right? Why not make that connection explicit in this way? Some people think poetry is a fancy-pants thing you read because some teacher told you to. Those same people love music without realizing poetry does many of the same things.

- The “call and answer” adds another voice to the poem, even though it’s only being written by one author. In this way, we’re able to produce a kind of harmony.

- The images and ideas in the poem are reinforced through repetition and through being conceptualized in a different way.

- The phrases on each side of the large spaces can be considered poems unto themselves and these poems are in conversation with each other, aren’t they?

One of the inherent difficulties in writing is bridging the gap between thought and the written word…and trying to figure out how to combine words, space and punctuation in such a way that the reader will understand the thought you had. Ms. DolRayne literally adds in the pauses that led me to treat her poem like a kind of song. For the poet, those pauses are spaces between words. For a singer, those pauses are bits of silence between musical phrases. Why not take Ms. DolRayne’s idea and try to lay down some prose in the style of a musician?

I think one of the reasons that I identified the call-and-answer conceit in the poem is because the poem was challenging me, inviting me to make sense of it in a way that made me happy. If you’re near a window, look out at the clouds. What shapes you do see? A phenomenon called “pareidolia” forces us to make sense out of “vague or random” stimuli.

Now, that’s not to say that Ms. DolRayne has given us a poem filled with randomness, because she didn’t. That’s writing craft in a nutshell, folks. The poet had to work very hard to create a work that clearly communicated her own thoughts while ensuring the piece was open enough to allow the reader to draw his or her own conclusions.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy method by which writers can learn to be simultaneously specific and vague. That’s just not something you can learn with a step-by-step procedure. Instead, we just need to read a lot of poems and write a lot of poems and hope that our skills improve to the point where we have the power to turn any trick we like.

What Should We Steal?

- Think of yourself as a songwriter when you compose. The conventions of music are not exactly the same as the ones writers use, but we can use their prose equivalents to our advantage.

- Trigger your reader’s pareidolia. How can you get your reader to see the plan in what seems like randomness?

Poem

2014, Conceits, inter|rupture, Janelle DolRayne, Ohio State

Show Notes:

Enjoy this interview with Wendy J. Fox, author of The Seven Stages of Anger, a short story collection published by Press 53.

Purchase The Seven Stages of Anger:

http://www.press53.com/bioWendyJFox.html

Find out more about Wendy J. Fox:

http://www.wendyjfox.com/

Visit the web site of BookBar:

http://www.bookbardenver.com/

Like the bookstore on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/BookBarDenver

Book You Should Buy: Backswing by Aaron Burch

http://www.queensferrypress.com/books/backswing.html

Find out more about Aaron Burch:

http://aaronburch.tumblr.com/

Better Know a Buckeye: Allison Davis

http://www.allisondavispoetry.com/

http://www.greatwriterssteal.com/2013/09/04/gws-essay-how-to-and-how-not-to-steal-writing-about-animals-by-allison-davis/

Purchase Ms. Davis’s book:

http://www.kentstateuniversitypress.com/2012/poppy-seeds/

Website: http://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Short Story Collection, Video

Aaron Burch, Allison Davis, Backswing, Carrie White, Ohio State, Press 53, Wendy J. Fox

If you heard my craft interview with Jac Jemc, author of A Different Bed Every Time, you heard her give away one of her secrets to writing beautiful sentences:

A lot of what I do before I start working is gathering language from other sources…I steal a lot. So what I’ll do is I’ll just sort of scan pages of books I’m reading and pull out words that are most vivid and exciting to me and try to pair them in ways…It’s just an exercise in trying to match things up in a way I wouldn’t normally do.

I also will look at texts in other languages that I know poorly…I’ll try to read something complex in one of those languages and translate it, but for the most part, it’s wrong. Maybe I’m getting 25 to 50 percent of it right, but the way that I force myself to bridge those little gaps with cognates and things, it creates some fun language.

So let’s try it!

Can you read Latin? I wish I could. Here’s the original Latin text of the Magna Carta. Isn’t it amazing how you can pick up a little bit of what the document says? I know “rex” means “king.” I know “Dominus” because of “dominate.” “Hibernie” must be an old form of “Hibernia.”

If I were writing a fantasy or science fiction story, it would be a great idea to do an awful translation of the Magna Carta and use the result as the founding document of a government you create for the piece. It would also be fun to pluck the words and sentences you like best and use them as dialogue for a character who speaks an alien or dead language. Latin speakers would get the joke, and the rest of us would simply get the drift.

John Williams did something similar when he composed “Duel of the Fates” for Star Wars. He needed his chorus to sing some lyrics that sounded big and magical and timeless and meaningful…so he set the piece to a loose Sanskrit translation of “Cad Goddeu,” an ancient Welsh poem.

Think about it…would the piece sound as powerful if it had English lyrics?

Get him…

Beat him up…

He’s a…

Real bad guy…

He has…red blades…on his…saber.

Wants to…kill the…good guy…Jedi.

Noooooooooooooooo…

No, that wouldn’t work. Instead, we should follow Ms. Jemc’s lead and play with languages in which we’re not quite fluent.

Want to try it yourself? Here are some examples of some documents that should be fun to translate:

Here are Martin Luther’s original Ninety-Five Theses. And here‘s an English translation.

Here‘s the German original of Goethe’s Faust.

Here‘s the French original of Molière’s Tartuffe.

Here are Nostradamus’s original quatrains.

Another facet of Ms. Jemc’s work that I admire is that she likes to work from prompts at times. You may have heard my reaction; I love to “write to order” sometimes. Ms. Jemc was asked to write a piece for a Melville House book intended to compile short stories for each of the Presidents of the United States. (Not the band, the actual people.) Ms. Jemc was lucky indeed to draw the assignment to write about Thomas Jefferson; a particularly interesting POTUS.

Here’s the result: “Head and Heart.”

It is, of course, impossible to chronicle every current call for submissions that includes a specific prompt or theme. There are, however, plenty of web sites that do an awfully good job trying to keep up.

Duotrope is probably the gold standard for market listings. For a small sampling of what they offer, check out their Twitter feed.

The Calls for Submissions Facebook group has 23,000 members! You’ll find lots of solicitations there; many of which are from editors looking for prompt-related material.

Do you know about NewPages? You certainly should! They’re one of the few outlets where you’ll find reviews of literary magazines. NewPages also maintains a classifieds section that features lots of great calls for submissions.

We might not be able to write exactly like Jac Jemc…but that’s okay! We’re all different writers. We can, however, exercise our skills by following her lead in a couple ways:

- Do bad translations of foreign prose to open our minds to new words and new ways of putting words together. We’ve been speaking and writing in our primary language so often and for so long that the rhythms of another tongue can shake us from our linguistic slumber.

- Find an interesting prompt and follow the rules they provide to produce a new work. Writers love to have freedom, but cool things can happen when we restrict our creativity a little bit.

Exercises, Short Story

Dzanc Books, GWS Exercise, Jac Jemc

Enjoy this interview with Jac Jemc, author of A Different Bed Every Time, a short story collection published by Dzanc Books.

Purchase A Different Bed Every Time:

http://www.dzancbooks.org/our-books/a-different-bad-everytime-by-jac-jemc

Find out more about Jac Jemc:

http://jacjemc.com/

Show Notes:

Visit the web site of Women & Children First:

http://www.womenandchildrenfirst.com

Like the bookstore on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Women-Children-First-Bookstore/8326741337

Book You Should Buy: Fobbit by David Abrams

http://www.davidabramsbooks.com/

Buy the book here:

http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/fobbit-david-abrams/1109170055?ean=9780802120328&itm=1&usri=fobbit

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780802120328/david-abrams/fobbit

Better Know a Buckeye: Erin McGraw

http://www.erinmcgraw.com/

http://www.greatwriterssteal.com/2013/01/26/what-can-we-steal-from-erin-mcgraws-punchline/

Purchase Erin’s books:

http://www.amazon.com/Erin-McGraw/e/B001ITRD0W/ref=dp_byline_cont_book_1

Website: http://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Short Story Collection, Video

David Abrams, Dzanc Books, Erin McGraw, GWS Video, Jac Jemc, Ohio State, The Great Writers Steal Experience

Title of Work and its Form: “Buckle Up,” short story

Author: Matt Carmichael (on Twitter @mttcarmichael)

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the September issue of Bartleby Snopes. You can read the story here.

Bonuses: Here is a story Mr. Carmichael published in The Adirondack Review. The gentleman has also done great work as the managing editor of TriQuarterly, a great journal.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Settings

Discussion:

This is the story of the lengths to which a parent (a father, in this case) will go to ensure their kids have happy Holidays and believe in the magic the world can possess. The first person narrator of the story has an important and morbid job: he tallies the traffic deaths for the year so the number can be displayed on the Highway Department’s roadside signs. The gentleman seems to enjoy his work, as work goes, and he is looking forward to the office holiday party. Bren, the narrator’s coworker, dresses up like Santa Claus to impress his son Tony, for whom this may be the last believing-in-Santa Christmas. Saint Nick eats cookies, right? Well, Santa Bren is offered some treats that contains peanut butter. Bren is allergic, but eats a cookie anyway, so as not to disappoint Tony. The ensuing heart attack puts a damper on the party, but the narrator concludes the story by pointing out that he lost the office traffic death pool and that Bren should be fine soon, as “heart attacks heal quick.”

What a morbidly funny story! Mr. Carmichael ensures that the piece’s structure is quite solid. The first aspect of the story on which I’d like to focus is that “Buckle Up” takes place in a workplace. The great Lee K. Abbott once pointed out to those of us who were in his class that there aren’t as many “work” stories as you might think there would be. After all, people spend more than a third of their lives at or on their way to work. Why wouldn’t we have a higher proportion of stories in those settings? Well, Mr. Carmichael makes the setting of the story seem as simultaneously dreary and pregnant with drama as you might expect from your own work experiences.

Let’s play advocatus diaboli for a moment. What if Mr. Carmichael made the wrong choice; what if he should have told another of the narrator’s stories? One that was more his own? The narrator certainly has his own life going on; a decent job, he likes Mountain Dew, he can string together fun sentences…why not send him on his own adventure instead of forcing him to describe what is probably Bren’s story? Well, Mr. Carmichael can always write more stories about the guy if he wants to do so. Further, the narrator seemed to be to be fairly passive and maybe even adrift in his own life, anyway. Why not let that kind of person tell the kind of story with which he’s more comfortable?

Because the author adheres strongly to “traditional” story structure, there’s a defined climax of the story: Poor Santa Bren has eaten a whole peanut butter cookie and is having a bad reaction and a heart attack. Then:

“Ho, ho, ho,” says Bren. He’s gasping for air. “This Christmas, Santa wants an epinephrine pen.”

He stands up and then keels over onto the floor. Francis yells, “buckle up, people, this is the real deal” and calls 9-1-1. Bren’s wife runs to his desk and ravages through his drawers. She says she thinks he keeps one of those pens at work.

What is Mr. Carmichael doing with the climax of his story? Why, he has set up a comic setpiece! Shakespeare did it, giving Will Kempe the fun and funny role of Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing. You’ll find the same principle in a ton of comedy films.

John Belushi has less screen time in Animal House than you would have thought. Ramis, Kenney, Miller and Landis, however, are smart enough to let Belushi dominate the moments of BIG comedy in the film. For example:

The 40-Year-Old Virgin is a comparatively quiet comedy film…until Steve Carell’s character is given a big comic setpiece:

Mel Brooks allows the whole narrative of Spaceballs to percolate until the big climax of the film, as all of the characters are trying to escape from the Mega Maid. With all of that storytelling pipe laid, the fantastic Mr. Brooks can let the physical comedy fly:

I guess what I’m saying is that I admire that Mr. Carmichael put a physical comedy setpiece into his short story; that’s not something you see every day. (But maybe it should be!) We chuckle as we finish “Buckle Up,” imagining Santa Bren gripping his itchy neck and flailing about as his wife tries to pull back his red pants to expose enough skin for the injection he needs.

What Should We Steal?

- Set a story or poem at work. Work may not be your favorite place, but the situations you experience there are pretty universal and audience-friendly.

- Cast a comic setpiece in prose. Why can’t a short story be as funny as a Saturday Night Live sketch?

Short Story

2014, Bartleby Snopes, Lee K. Abbott, Matt Carmichael, Santa Claus, Settings, TriQuarterly

Friends, there are about eleventy million great writers out there and eleventy trillion great stories. There’s simply no way to keep up with every worthwhile work that comes out. Still, we must have a working knowledge of what came before us if we’re going to break new literary ground. That’s why I’m dipping into my local library’s near-complete collection of Best American Short Stories to take the pulse of a different time and place. So hop in the time machine with me because we’re going all the way back to…

1996. Michael Jackson was only on his third nose. Carson Daly had exactly the same number of talents as he has now. Derek Jeter was on his way to winning the AL Rookie of the Year.

More importantly for our purposes, Issue 94 of TriQuarterly was hot from the presses, marking the first publication of Dan Chaon‘s “Fitting Ends.” If you don’t have a copy of TriQuarterly 94 hanging around, don’t worry. The story was reprinted in Best American Short Stories 1996, as well as Mr. Chaon’s first collection. The author is, of course, one of our many big-time Literary Lions; he studied writing at Northwestern and Syracuse and currently teaches at Oberlin College. I haven’t had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Chaon, but he seems like a good person; check out this interview he gave to The Believer.

“Fitting Ends” is a melancholy story about a narrator whose older brother died when he was fourteen. The brother was hit by a train while under the influence of alcohol. Del died alone, so the family has spent the subsequent decades wondering what really happened and why. Mr. Chaon’s narrator maneuvers gracefully between past and present. We learn that Del’s death has become a form of retroactive evidence to support the claims of a ghost on the same tracks where he died. While Del had some adolescent problems and acted out, Del was also a very sensitive kid and even saved the narrator’s life. In the dramatic present, the narrator attempts to talk to his parents about Del’s death (and what really happened on the grain elevator), but the narrator seems to learn that these deep, dark truths sometimes remain that way because they can hurt more than they can help and that they may not matter in the end.

I love the way Mr. Chaon begins the story. A lesser writer (such as myself) may have tried to jumpstart the narrative by making more immediate use of the story’s BIG EVENT: Del’s death on the train tracks. Instead, Mr. Chaon deals with this inciting incident more obliquely:

There is a story about my brother Del that appears in a book called More True Tales of the Weird and Supernatural. The piece on Del is about three pages long, full of exclamation points and supposedly eerie descriptions. It is based on what the writer calls “true facts.”

Why is this great? There are a few reasons. First of all, I remember those TIME/LIFE books to which the author is referring. Those commercials were incredibly creepy and were on TV about ninety times a day; the reference is probably one that the reader “got” in 1996 and is still meaningful to us today, even if they don’t know about the book series. Here’s one of the commercials. Watch it and try not to be creeped out:

“Fitting Ends” is deep and resonant, but it isn’t the most ebullient and happy story ever written. If Mr. Chaon had begun with, “My brother Del was hit and killed by a train when I was fourteen…,” then the story may bum us out more than is necessary. Mr. Chaon manages to ease us into the pathos gently, allowing us to feel the eventual dull ache that the narrator probably feels with Del dead for over a decade. Further, this is a story about the manner by which people in a family learn to understand each other. (Or try to do so.) Mr. Chaon contrasts this intimacy by presenting us with the unlearned sensationalism of the outsider.

I also love the choice Mr. Chaon made with respect to the age of the narrator. The guy always loved Del, that much is clear. But the narrator now has a wife and a child of his own. He’s had many years to try and understand what happened. Mr. Chaon also allows us to see the narrator’s shame when he describes how, as a young adult, he used his brother’s story as a way to get girls. The point is that the narrator would not have been able to confront the family’s “Del issue” without so much time for their thoughts and feelings to percolate.

There’s a particularly sweet moment approximately 60% into the story. The reader knows a lot of the facts about Del’s death and has met his parents in the dramatic present. The narrator has made it clear that the story is, to some extent, about his desire to join his family in a deeper understanding of the young man’s death. We’ve learned about the family’s relationship with violence and the lies that flew between the sons and the father. Yes, Mr. Chaon could have given the narrator and the audience what they think they want: a long, drawn-out scene in which everyone reaches catharsis.

Mr. Chaon doesn’t disappoint us with this kind of easy answer. At one point, the narrator is visiting his family and he really wants to tell his father a secret. He thinks about his own son and is “chilled” by the way a father’s love can transform and “turn in on itself.” Mr. Chaon writes:

We looked at each other, my father and I. “What are you thinking?” I said softly, but he just shook his head.

The author makes the brave choice to leave words unspoken and emotions unshared. And look at the word he uses in the dialogue tag: “said” instead of “asked.” The narrator’s question doesn’t receive an answer because there really isn’t a satisfactory one out there.

What Should We Steal?

- Ease the reader into the inciting incident. Sometimes you need a whiz-bang open. Other times, you should let the reader stew in the juices of your conflict.

- Set your story in the time that is right for the narrator. People need time to reflect on big events before they can comment meaningfully…your characters are no different.

- Allow a quiet moment of discord to replace what could be a moment of epiphany. Stories should be like life; we don’t always get the answers we want. (Or the ones we need.)

Short Story

Best American 1996, Dan Chaon, GWS BASS Flashback, TriQuarterly

You’ll also notice that the last stanza abandons the conceit, which is perfectly fitting. The narrator of the poem is now speaking in “unison” or “a cappella.”

You’ll also notice that the last stanza abandons the conceit, which is perfectly fitting. The narrator of the poem is now speaking in “unison” or “a cappella.”