Title of Work and its Form: Tough Guys Don’t Dance, novel

Author: Norman Mailer

Date of Work: 1984

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book can be found in most cool secondhand bookstores. I’m willing to bet that list includes Provincetown Bookshop. (I could easily be mistaken-the time I spent on Cape Cod seems in my memory to have been lived by a character in someone else’s movie, but I seem to recall visiting that store and enjoying my time there a great deal.) You can purchase the book from your local indie or get it from a much larger indie.

Bonuses: The Norman Mailer Society is dedicated to preserving the legacy of Mr. Mailer’s work. J. Michael Lennon offers this brief appreciation of Mr. Mailer’s work. Mr. Mailer was a frequent talk show guest and this documentary was made about him after his death:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Genre

Discussion:

The novel starts on the twenty-fourth morning after Tim Madden’s wife decided she wanted to fly the coop. Madden is hung over and has a new tattoo on his arm: the name of a woman from his past. The passenger seat of his Porsche is drenched in blood. Over the course of the next several days, Madden unravels the mysteries that he only thought began when he met the beautiful rich blond and her ugly husband in his favorite Provincetown watering hole.

That’s right, the book is essentially a high-class pulp novel in the style of Mickey Spillane or Donald Westlake. Now, I love those kinds of books. I don’t aspire to the gunplay or liver damage, but isn’t it fun to spend a few hours in a completely different world? A place in which it’s not unusual to kiss The Dame Who Got Away or to walk into a room and smell evidence emanating from your gun that could put you back in the clink?

The first matter of craft that impressed me about Tough Guys Don’t Dance was the way in which Mr. Mailer attempted to “class up” a genre that is often unfairly maligned by critics. Okay, a lot of pulp novels are weighed down by cliches and clunky sentences. Fine. But STUFF HAPPENS in these books. The characters are FUN. There is MEANINGFUL SUSPENSE. Pulp detective novels are the spiritual forbear of TV programs such as Law & Order: SVU, a program that currently averages eight million viewers each Wednesday night. How many short stories are read by eight million people? How many books sell that many copies? (Gracious; if these numbers are to be believed, Catch-22 has only sold ten million copies!)

I suppose that what I’m urging at the moment is that we all make more of an effort to appreciate genre work and try our hands at branching out from what may be our comfort zones. Of course, writers are well within their rights to compose whatever works they like. But how cool would it be if Alice Munro took a crack at a post-apocalyptic science fiction thriller? What if John Irving woke up one morning and decided to write an epic fantasy poem? Perhaps it’s my personal preference speaking, but I love it when a great writer uses his or her most powerful gift-imagination-as completely as possible.

Now, what makes Tough Guys Don’t Dance a “high-class pulp novel?” I would assert that the book sets itself apart on the “literary” side by devoting a lot of time to characterization at minor expense to the laying of plot. In an Ed McBain book or a Day Keene book, the plot is always chugging along. Sure, McBain and Keene establish characters (and very cool ones), but Mailer devotes dozens of pages to backstories for Madden and his colleagues. Still, Mr. Mailer makes the shrewd choice of ending each chapter with a big, important and cool event, a revelation that makes us wonder what will happen next.

Chapter One: “Yet none of these scenarios, nor very little of them, can be true-because when I woke in the morning, I had a tattoo on my arm that had not been there before.”

Chapter Two: “…I did not even know whether it was the head of Patty Lareine or Jessica Pond lying in that grave. Of course, I also did not know whether I should be afraid of myself, or of another, and that, so soon as night was on me and I tried to sleep, became a terror to pass beyond all notions of measure.”

Chapter Four: “The head was gone. Just the footlocker with its jars of marijuana remained. I fled those woods before the spirits now gathering could surround me.”

Here’s the challenge: how do you end a chapter in a way that gets your reader’s pulse pounding while simultaneously stimulating his or her intellect?

What Should We Steal?

- Break out of your genre safe space and try something new. Why not dip your toe in the warm waters of crime, science fiction, fantasy or western stories?

- End your chapters with meaningful developments that advance the plot and will grab the reader on a high and low level. We read with our minds AND our hearts. Why not stimulate both?

Novel

Classic, Genre, Norman Mailer, Random House

Title of Work and its Form: “Falling,” poem

Author: James L. Dickey

Where the Work Can Be Found: “Falling” has been anthologized about ten trillion times. You can also find the poem on the Poetry Foundation web site.

Bonuses: Here is Mr. Dickey’s New York Times obituary. Here is an interview Mr. Dickey gave to The Paris Review. What did the poet hope would happen when people read his work? Check out his answer:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Punctuation

Discussion:

This “long” and fun poem tells a real-life story: that of a stewardess who fell out of a commercial airplane, meeting an unfortunate end at the hands of physics and fate. The poem begins as the woman is rummaging for blankets and completing her commonplace duties. Without warning, she is sucked out of the plane and falls to the earth. The plot of the poem may be simple, but it packs a big wallop because of the way Mr. Dickey uses language to describe her actions and thoughts as she endures what she learns will be the last couple moments of her life. The free verse work is split into seven stanzas that increase in intensity, culminating in a chilling final line:

There’s SO MUCH to learn from this poem that I should just jump right in, but I can’t help but point out one reason I’m writing about “Falling.” We all love Stephen King, right? Well, he gave an interview to The Atlantic‘s Jessica Lahey in which he discusses his views on craft and teaching. During a discussion regarding which kind of work has the biggest impact on young readers, Mr. King says:

When it comes to literature, the best luck I ever had with high school students was teaching James Dickey’s long poem “Falling.” It’s about a stewardess who’s sucked out of a plane. They see at once that it’s an extended metaphor for life itself, from the cradle to the grave, and they like the rich language.

Mr. King, of course, is correct in his assertions and “Falling” is the kind of poem we should all have under our belts.

What do we notice first of all? Well, Mr. Dickey stole the idea of the poem from a real news article. This one, in fact. Unfortunately, Mr. Dickey is no longer with us, so we can’t ask him about his exact motivation. It’s safe to say, however, that Mr. Dickey was probably struck by the terror and freedom the young woman experienced during her descent. Why shouldn’t you do the same thing? The next time you read a news story that strikes you, why not jot down a few lines. After all, most of us are moved by news stories and anecdotes we hear and the like. We’re never at a loss for inspiration if we make use of the infinite number of stories that surround us. There are also infinite angles you can take when borrowing from the news. You can simply retell the story. Or you can set the events 500 years in the future. Or you can devote the narrative to an observer. Or you can do as Mr. Dickey did, delving deep into what he imagined the stewardess was thinking and doing as the surly bonds of Earth reclaimed her.

And now, it’s time to do a little counting. I know…I know…so many of us become writers because we don’t want to deal with a ton of numbers. Unfortunately, statistical analysis can help us understand what makes “Falling” so effective. You’ll notice that Mr. Dicket doesn’t cast his lines in a traditional manner. That’s just fine, of course; the fragmented run-on lines mimic the stewardess’s mental state. I’m betting that it’s pretty hard to form coherent sentences when you’re at terminal velocity without a parachute.

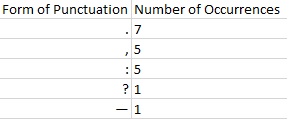

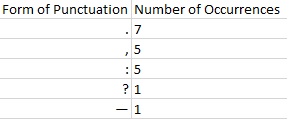

Mr. Dickey still had an obligation to help us figure out how we should split up the lines. And he also has the responsibility to let the reader take a breath. (We don’t want people to pass out at poetry readings, do we?) So how does he manipulate the prose to allow respiration and to communicate the feeling of disjointed thought? Well, you see all of those spaces in the fairly long lines. But you’ll notice that he also uses punctuation, albeit sparingly. Here’s a table that breaks down his use of punctuation in the poem:

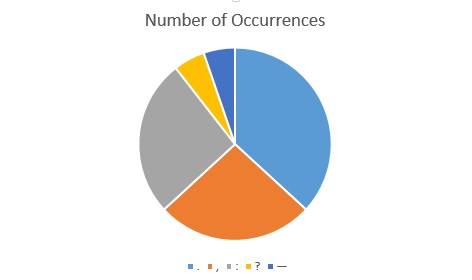

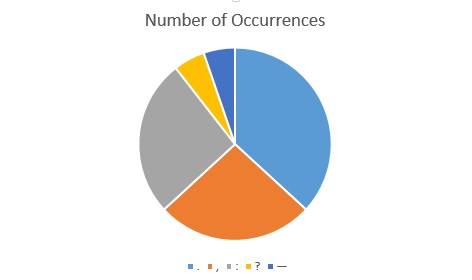

Want to see the data in chart form?

Want to see the data in chart form?

Only 19 punctuation marks? In such a long poem? Crazy!

Well, not really. Mr. Dickey used the punctuation like spice, placing the marks only where they were utterly necessary. You’ll also notice that the end of the poem-the time when the character is most despondent, we might assume-only includes two marks, including the one at the very end. By that time, Mr. Dickey has taught us how to read the poem; he doesn’t need to provide the kind of guideposts that were much more of a necessity earlier in the poem. What’s the overall point? We must string together words in the manner appropriate to the work and mortar them together with the proper punctuation…even if that means omitting the marks altogether.

Another great thing about the poem is that Mr. Dickey actually gives the fictionalized protagonist things to do. Now, the unfortunate real-life stewardess may not have imagined she could save herself by diving into water. She may not have removed her jacket and shoes on purpose (or at all). It’s sad, but we have no way of knowing what she was thinking because she wasn’t around to tell us the next day. One of the big problems that a lot of people have when they fictionalize a real event is a lack of imagination. (At least, this failure is certainly a problem for me!)

When we are molding creative works, we shouldn’t forget that we can change anything we like about the characters and the plot. What a freeing notion, right? Like me, you may think of the perfect thing to say to someone…an hour after you should have said it. These restrictions are loosened in creative writing. By all means, if you are writing about your childhood, your best friend doesn’t have to live next door. Your first boyfriend or girlfriend doesn’t have to break your heart and show up to school looking blissful the next day. It’s not entirely necessary that your parents got divorced. Why? The characters aren’t really your best friend, significant other or parents. It’s your world, friend. You get to decide what joys and pains your characters endure.

What Should We Steal?

- Write your own version of a true story. What was going through the minds of American sailors during the attack on Pearl Harbor? What were the Japanese kamikaze pilots thinking?

- Shape your lines and use punctuations according to your needs. If you are trying to craft breathless lines for a breathless character, you might not want to use a lot of periods. (Periods are also called “full stops.” Stopping certainly wouldn’t be a good idea for this kind of character.)

- Feel empowered to fictionalize real-life situations. You are your characters’ puppet master. Pull the strings. But don’t take my word for it. Take the advice from Bela Lugosi:

Poem

Classic, James Dickey, Punctuation, Stephen King

Title of Work and its Form: “The Curious Thing About Women,” an episode of The Dick Van Dyke Show

Author: Written by David Adler, Directed by John Rich

Date of Work: Originally broadcast on January 10, 1962

Where the Work Can Be Found: The episode can be found on the Dick Van Dyke Show DVD collection. As of this writing, it is streaming on Netflix.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: The Creative Process

Discussion:

The Dick Van Dyke Show ended nearly fifty years ago, but it is still one of the best programs in television history. Carl Reiner drew on his experience as a writer and performer on Your Show of Shows and created Rob Petrie (Dick Van Dyke), head writer for The Alan Brady Show, a variety program. Rob has a beautiful and intelligent wife named Laura (Mary Tyler Moore) and works with two great comedic minds: Buddy and Sally (Morey Amsterdam and Rose Marie). While plenty of stories were focused on Rob’s glamorous job, what really set Dick Van Dyke apart was Reiner’s ability to depict Rob’s very normal home life.

“The Curious Thing About Women” begins as Rob is eating breakfast, preparing to make the drive from New Rochelle to Midtown Manhattan. He is upset to discover that his wife, Laura, has already opened and read all of his mail. Rob and Laura have an extremely healthy fight before Rob heads to work. Rob, Buddy and Sally need to come up with a sketch for Alan Brady…they hit upon the idea of making Rob’s anecdote into a sketch. You have a wife who claims she isn’t insanely curious about what is in her husband’s mail. Of course, the wife becomes insane and opens the mail. When the sketch airs, Laura is not happy at being labeled a “pathological snoopy-nose.” Rob and Laura have another fight; this one is a little less pleasant, but it’s still healthy. The next day, Rob is at work when a package is delivered for him. What happens? The inevitable: Laura’s curiosity overtakes her. She opens the package, which turns out to be an inflatable boat. Rob returns (of course) and simply asks the woman hiding behind the giant boat, “Did a package come for me?”

Look at that second scene, as Rob, Buddy and Sally are in the office, trying to write a sketch. Is there a writer who can’t relate? Who hasn’t stared at a blank page wondering what the heck they are going to write? And how many zillions of writers have dreamed of a career in a writer’s room because of the show? (I’m one of them, obviously.) Three brilliant writers are batting around ideas. Rob, Buddy and Sally build on every good idea and shoot down every mediocre one. By the end of the scene, they have a great sketch. Just like tempered steel, great works are forged over time and are the result of lots of sometimes tedious work.

Perhaps it’s just me, but I remember being able to see the ending coming during my long ago first viewing of the episode. Rob writes a sketch about his wife opening a boat. Rob’s boat arrives. What else could Laura do but open the package and wrestle the boat? The climax of Mr. Adler’s script may be a little bit predictable, but it is inevitable. Doesn’t this mimic the way life works? If you treat your boyfriend or girlfriend poorly for an extended length of time, isn’t a breakup inevitable?

Mr. Adler also follows the rule of threes.

- Rob mentions he bought an inflatable Army surplus boat that will soon be delivered

- Laura watches the Alan Brady sketch in which the curious wife inflates the boat

- Laura opens the package and inflates the boat

The audience is warned what will happen and a kind of suspense is built. Laura gets to see the sketch on the television, but the audience doesn’t. Mr. Adler’s script allows the audience at home to share Laura’s experience, just as they likely share the experience of arguing with a spouse, only to be proven wrong.

What Should We Steal?

- Bounce ideas around with friends (or alone) to give them the freedom they need to mature. Ideas need to be distilled. They need to percolate. If you combine the results of those two concepts, you get Irish coffee, which may or may not help you write.

- Prepare your audience for the climax of the piece. Would we laugh if Laura inflated the boat in the first thirty seconds of the episode? We wouldn’t laugh because the bit wouldn’t mean anything to us. After twenty-five minutes of preparation, there are stakes attached to Laura opening up the package, boosting the humor and the drama.

Television Program

1962, Classic, David Adler, Dick Van Dyke, John Rich, The Creative Process

Title of Work and its Form: “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” short story

Author: James Thurber

Date of Work: 1939

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story first appeared in The New Yorker’s March 18, 1939 issue. Wow…believe it or not, Zoetrope: All-Story has posted the story online. Very cool, Francis Ford Coppola.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Reader Orientation

Discussion:

James Thurber is one of the greatest writers and humorists of the twentieth century. The man was prolific and famous. (Can you believe it? A famous writer?) He was a native of Columbus, Ohio—Go Bucks!—and you can even visit his home. Thurber House is a museum and an important part of the thriving Columbus literary scene. Perhaps his most famous story, “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty” was made into a 1947 film starring Danny Kaye. The film is being remade, of course, and will be directed by its star, Ben Stiller.

The story is short and sweet, though it isn’t simple. Walter Mitty brings his wife to her appointment at the hairdresser. But don’t drive too fast! And while he’s waiting, could he pick up a dog biscuit? And don’t forget that new pair of overshoes. And don’t be late! Walter Mitty deals with the emasculation and mundanity of his life by relaxing into periodic fantasies. Instead of being a henpecked husband, he’s a highly respected surgeon and a war pilot and a crack shot “with any known make of gun.”

A lot of folks (myself included) enjoy messing around with time and place in narrative. Flashbacks are fun. Hypothetical looks into the future are fun. The problem is that it can be hard to bring the reader along with you. Why don’t the transitions in “Mitty” confuse the reader? Let’s look at the beginning of the story:

“We’re going through!” The Commander’s voice was like thin ice breaking. He wore his full-dress uniform, with the heavily braided white cap pulled down rakishly over one cold gray eye. “We can’t make it, sir. It’s spoiling for a hurricane, if you ask me.” “I’m not asking you, Lieutenant Berg,” said the Commander. “Throw on the power lights! Rev her up to 8,500! We’re going through!” The pounding of the cylinders increased: ta-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa-pocketa. The Commander stared at the ice forming on the pilot window. He walked over and twisted a row of complicated dials. “Switch on No. 8 auxiliary!” he shouted. “Switch on No. 8 auxiliary!” repeated Lieutenant Berg. “Full strength in No. 3 turret!” shouted the Commander. “Full strength in No. 3 turret!” The crew, bending to their various tasks in the huge, hurtling eight-engined Navy hydroplane, looked at each other and grinned. “The old man will get us through” they said to one another. “The Old Man ain’t afraid of Hell!” …

“Not so fast! You’re driving too fast!” said Mrs. Mitty. “What are you driving so fast for?”

“Hmm?” said Walter Mitty. He looked at his wife, in the seat beside him, with shocked astonishment. She seemed grossly unfamiliar, like a strange woman who had yelled at him in a crowd. “You were up to fifty-five,” she said. “You know I don’t like to go more than forty. You were up to fifty-five.” Walter Mitty drove on toward Waterbury in silence, the roaring of the SN202 through the worst storm in twenty years of Navy flying fading in the remote, intimate airways of his mind.

So the story begins with the climax of an adventure. Mitty is piloting the hydroplane into the gaping maw of danger—when his wife nags him for driving too fast. While there is a brief sense of disorientation, Thurber gently guides the reader into understanding. Look at that ellipsis. Immediately following that is a line of dialogue that does NOT fit into the hydroplane narrative. Then Thurber gives us that all-important exposition. Walter Mitty is in a car. With his wife. He’s going to Waterbury, driving through a storm. What does that ellipsis mean? (I turned it red in hopes of making it more obvious.) We know that the ellipses bookend a fantasy. The signal is simple and powerful and helps the reader enjoy the idiosyncrasies of the story instead of being stymied by them.

What Should We Steal?

- Play with your reader, but make sure you guide him or her along. It’s your solemn duty as a writer to give the reader what he or she needs to understand your story. Confusion and disorientation should only be used for effect and should only be temporary. They should not be an ultimate goal.

- Establish clear signals. An ellipsis can be the difference between reality and fantasy.

Short Story

1939, Classic, James Thurber, Ohio State, Reader Orientation

Title of Work and its Form: “Reunion,” short story

Author: John Cheever

Date of Work: 1962

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was originally published (where else?) in The New Yorker. You can find it in Cheever’s Collected Stories. Hey, check it out! Here’s a recording of Richard Ford reading the story that is hosted on The New Yorker’s web site.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Communication of Pathos (Emotion)

Discussion:

“Reunion” is as short as it is powerful. Charlie, the first-person narrator, describes the brief reunion he had with his father. Charlie was a kid at the time and all Dad wanted to do was drink and…well, that’s about it. Charlie gets on the train, never to see his father again.

The narrator is so calm in the story, even though you know that there’s a lot of emotion wrapped up in the experience. One way that you can tell is the frame into which Cheever has painted the story. Here’s the first sentence:

The last time I saw my father was in Grand Central Station.

And here’s the last one:

“Goodbye, Daddy,” I said, and I went down the stairs and got my train, and that was the last time I saw my father.

There’s a symmetry to the story, as though the narrator has closed a chapter of his life and has made it clear to the reader that he has no more to say on the subject. You don’t have to be told explicitly; you can feel the closing of a door.

There’s further repetition at the end of the story. Charlie calls his father “Daddy” three times. Three is a magic number, isn’t it? Can you hear the different tones in which young Charlie would use the word?

- Calmness.

- Sadness.

- Emotional detachment.

(You’re free to have differing opinions; you see the point.)

Cheever packs a lot of pathos into “Reunion” without really offering much explicit insight into the narrator’s thoughts. Instead, Future Charlie reports the events and we are invited to make our own conclusions as to what he is feeling. Doesn’t this mimic the process by which we do the same thing in our own relationships?

What Should We Steal?

- Employ repetition to communicate emotion. It is often far more fulfilling to understand something by figuring out the subtext instead of simply being told. This is also the way that so many emotions are communicated in real life. A dissatisfied significant other may not sit you down and tell you how they feel. They will, however, repeatedly treat you in a manner that should clue you in.

- Make use of three, the magic number. Three just feels natural for some reason. Beginning, middle, end. Father, Son, Holy Spirit. Larry, Moe, Curly. Tinker to Evers to Chance.

Short Story

1962, Classic, Communication of Pathos (Emotion), John Cheever, The New Yorker

Title of Work and its Form: The Godfather, film

Author: Directed by Francis Ford Coppola, Written by Mario Puzo and Coppola from Puzo’s novel.

Date of Work: 1972

Where the Work Can Be Found: The film has been released on DVD.

Element of Craft We’re Going to Steal: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

The Godfather is one of the many films you REALLY MUST SEE if you want to be a writer. The structure is solid, the characters are lush and fully rendered and there’s violence with actual consequences. If you watch the film, you’ll even get a great recipe for tomato sauce! The film tells the story of the Corleone Family and how the initially reluctant son Michael (Al Pacino) becomes the don. Vito Corleone (Marlon Brando) does his best to conduct business in an “honorable” fashion, resisting the push deal drugs. (After all, the numbers racket and prostitution don’t hurt anyone in the way drugs do.) If you haven’t seen the film, just go see it.

Right now, I’m only talking about the very beginning of the film, so there shouldn’t be any spoilers. Puzo and Coppola’s screenplay accomplishes a LOT in the first five minutes. Best of all, the scene is as simple as it is powerful; it’s just Don Corleone talking with Bonasera, the owner of a funeral parlor.

What are the first words? “I believe in America.” In reality, “America” is an idea as well as a tangible entity. “America” means something different to everyone in the film. Bonasera describes how his daughter has been raped by two men who get a slap on the wrist. Bonasera begs Don Corleone for justice, hoping he will use his resources to have the rapists killed. “America” failed him. He tried to live by the rules and trust our nation of laws, but his daughter didn’t receive justice.

Don Corleone is offended by Bonasera. He laments that Bonasera has never treated him like a true friend. Bonasera has never asked him over for a simple cup of coffee and has foresaken the fact that Vito’s wife is his child’s godmother. Only after he discusses personal matters does Don Corleone discuss business. We learn in the first few minutes of the film that, to Don Corleone, personal relationships are more meaningful that official legal ones. America seems to be a place where a pure sense of justice can be more easily forged than in the Old Country. The Don isn’t bloodthirsty; he calmly refuses to have the men killed. After all, “[Murder] is not justice; your daughter is still alive.” Only when Bonasera submits to Don Corleone, by kissing his hand and calling him “Godfather,” does Vito agree to do the requested favor.

The scene is so powerful because the big themes of the film emerge from a relatively small discussion between two people. The viewer is immediately immersed in the BIG THEMES of The Godfather without being beaten over the head with them. The intimate scene is also immediately contrasted with a much larger, more public one: the wedding of the Don’s daughter. The juxtaposition allows us to understand the Don’s morality in the larger context of the world he inhabits.

What Should We Steal?:

- Start a story with a calm but meaningful scene that introduces your central themes. It can often be tempting to start our stories with BIG acts and EXPLOSIONS and FIREWORKS. Sure, the Don ends up ordering an assault, but the calmer introduction here allows the audience to become comfortable with the Godfather’s unique world before the fireworks happen. (I’m thinking the scene between Sonny and his brother-in-law.)

- Allow your characters to have complicated ideas about the world and unexpected concepts of morality. In a boring story, everything is black and white. Mobsters are monsters who only care about money. The bad guy is bad just because he is bad. In The Godfather, the characters have motivations that are sometimes unexpected.

Feature Film

1972, Classic, Francis Ford Coppola, Mario Puzo, Marlon Brando, Narrative Structure

Title of Work and its Form: The Importance of Being Earnest, play

Author: Ernest Hemingway

Date of Work: 1895

Where the Work Can Be Found: The play appears in all kinds of anthologies. Thanks to the wonders of public domain, the play can be found on the Internet. (In your face, Sonny Bono and Mickey Mouse!)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Characterization

Discussion:

The Importance of Being Earnest is, quite simply, one of the best comedies around. Not only is there a laugh every fifteen seconds, but the characters are compelling and charming. Best of all, it’s a love story! Don’t we all enjoy a good love story? John Worthing and Algernon Moncrieff are…committed bachelors…wink wink…right? Get it? All they want is to find women with whom they can settle down. The course of their true love doesn’t run smoothly at all. Each of them assume the name Ernest as a way to remain anonymous while having fun. Algernon also pretends to have a friend named Bunbury who serves as a convenient excuse when he wants to take off. Enter Gwendolyn and Lady Bracknell. Gwendolyn is a sweet and beautiful young woman; John/Earnest proposes marriage. (She loves guys named Ernest.) Unfortunately, John is not satisfactory marriage material; his mother stuffed him in a handbag as a baby and left him in a train station. Long story short: a ton of coincidences are discovered and everyone ends up happy and married at the end.

Lady Bracknell is my favorite character from the play. She’s an older woman who epitomizes the Victorian ideals of propriety. The most important thing, of course, is not actual propriety, but the appearance of propriety. (Do we have anyone like that?) Lady Bracknell doesn’t worry too much about money, which gives her the luxury of living life “properly.” Her clothing is always perfect and a judgmental quip is always on her tongue. Freed from the struggles of “normal” life, she is free to tell others what to do. And the dialogue Wilde gives to her couldn’t sparkle any more brightly.

Let’s look at Lady Bracknell’s entrance and first lines. (Always a good idea.)

[Algernon goes forward to meet them. Enter Lady Bracknell and Gwendolen.]

Lady Bracknell. Good afternoon, dear Algernon, I hope you are behaving very well.

Algernon. I’m feeling very well, Aunt Augusta.

Lady Bracknell. That’s not quite the same thing. In fact the two things rarely go together. [Sees Jack and bows to him with icy coldness.]

Wilde wastes no time! Lady Bracknell follows the social script by asking how-do-you-do and then reprimands Algernon, doling out one of her legendary pronouncements. We don’t often think deeply about these kinds of perfunctory situations, but Lady Bracknell is right; behaving well and feeling well are two very different things.

We love Lady Bracknell because she is relentless and devoutly committed to her beliefs. Unlike wishy-washy people, she creates drama by being inflexible and unforgiving. Here are some more of her lines:

I’m sorry if we are a little late, Algernon, but I was obliged to call on dear Lady Harbury. I hadn’t been there since her poor husband’s death. I never saw a woman so altered; she looks quite twenty years younger.

Well, I must say, Algernon, that I think it is high time that Mr. Bunbury made up his mind whether he was going to live or to die. This shilly-shallying with the question is absurd. Nor do I in any way approve of the modern sympathy with invalids. I consider it morbid. Illness of any kind is hardly a thing to be encouraged in others. Health is the primary duty of life.

An engagement should come on a young girl as a surprise, pleasant or unpleasant, as the case may be. It is hardly a matter that she could be allowed to arrange for herself . . .

I have always been of opinion that a man who desires to get married should know either everything or nothing. Which do you know?

It’s true that Oscar Wilde stole a little bit of Lady Bracknell’s character from similar characters in farces that preceded Earnest. In the years since I read the play, I have noticed some examples of television writers doing what Wilde did: taking a character “type” and putting a unique spin on it.

Arrested Development’s Lucille Bluth (Jessica Walter) is a wealthy woman who cares only about appearances. She’s forever telling her children and her husband and her adopted child Annyong and her grandchildren and the painters and the household help how they should live their lives and what is “right” and “proper.” Fun example: Lucille constantly criticizes her daughter Lindsay’s weight. They share this exchange in a restaurant:

Lindsay: Did you enjoy your meal, Mom? You drank it fast enough.

Lucille: Not as much as you enjoyed yours. You want your belt to buckle, not your chair.

Two and a Half Men’s Evelyn Harper (Holland Taylor) is a wealthy woman who cares only about appearances. She’s forever telling her children and grandchildren how they should live their lives and what is “right” and “proper.” Fun example: in one episode, Evelyn is excited to attend a party in her honor and to soak up attention. Unfortunately, she is upstaged by the singing of the housekeeper’s sister. In a moment of reflection, she lets loose this very Bracknell line:

Evelyn Harper: Why does anyone want a party? To feel superior while feigning humility!

What Should We Steal?

- Take a stock character and make him or her your own. These words can be very confusing. They can also characterize the attitude of a character or narrator.

- Make the most of the entrances your characters make. Your audience or reader should understand your characters within seconds of meeting them. Sure, you may change the perception you create later in the piece, but your characters are actors at heart. They want to make big waves and burn themselves into the audience’s memory instantly.

Play

1895, characterization, Classic, Oscar Wilde

Title of Work and its Form: “Everyday Use,” short story

Author: Alice Walker

Date of Work: 1973

Where the Work Can Be Found: The short story has been anthologized in about a million collections. (And with good reason!)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Voice

Discussion:

“Everyday Use” is one of my favorite short stories for a lot of reasons. I love the simplicity of the story and the narrator, a woman who is equally proud and vulnerable, simultaneously tough and loving. Mrs. Johnson, along with her younger daughter Maggie, awaits the return of Dee, the daughter who got out of the small town and went to college. Dee returns with a different style of dress and a different name: Wangero. There’s also a boyfriend named Hakim-a-barber. (Mrs. Johnson has misheard the Arabic; I believe his name is “Hakim Akbar.”) Having seen a different way of life, Wangero is no longer pleased with the way she grew up. There is a fight over some quilts; Wangero wants to hang them and cherish them as an artifact of African-American culture and Mrs. Johnson expects Maggie will get them and will use them as, well, quilts. You know, for warmth when it is cold. Wangero and Hakim-a-barber leave after a short argument over what “heritage” really means.

Whenever you write a first-person narrator, it’s vital that you understand the way their voice should sound. Mrs. Johnson is not “book smart,” as her education was ended for her after second grade. (The school was closed. As she points out, “in 1927 colored asked fewer questions.”) It’s therefore unrealistic that Mrs. Johnson would, for example, start quoting Shakespeare or use a lot of “big” words. Walker instead restricts herself to employing fairly short sentences. The poeticism comes through in the more “rural”/”down-home” expressions that Mrs. Johnson uses. Mrs. Johnson is not at all simple-minded; she just expresses herself in a less complicated manner than might be the case if she had more formal education.

Mrs. Johnson describes a dream in which she is erudite and classically beautiful and famous. This dream is immediately followed by the truth: “In real life I am a large, big-boned woman with rough, man-working hands.” Walker introduces the central conflict of the piece while setting the tone. There is rich fantasy in the lives of Mrs. Johnson and Maggie, but that fantasy is as strong as reality. We trust the narrator because she is telling us the story straight.

“Everyday Use” could be considered a kind of attack against Wangero and the fantasy she has chosen. Instead, Mrs. Johnson primarily restricts herself to observing and reporting. There’s subtext in the climactic fight—

Dee (Wangero) looked at me with hatred. “You just will not understand. The point is these quilts, these quilts!”

“Well,” I said, stumped. “What would you do with them?”

—Mrs. Johnson reinforces a tone of loving indignance. Instead of flying off the handle and being vicious to her daughter, she calmly allows the reader to draw his or her own conclusions.

What Should We Steal?

- Match your character’s diction to his or her level of education and mindset. Now, Mrs. Johnson COULD have caught up with formal education on her own, but she didn’t. (She certainly seems very smart to me!) Therefore, Ms. Walker writes Mrs. Johnson’s thoughts in a conversational, relatively unadorned manner.

- Allow your subtext to emerge from the scene instead of making it excessively explicit. I guess this is one of the main reasons I’ve always loved the story so much. There is a HUGE debate going on in the story. What is identity? Who decides what we are and what we will be? How beholden are we to the past? How much should we respect the way we grew up? What does it mean to honor one’s parent(s)? Ms. Walker takes a step back narratively and allows Mrs. Johnson to simply report the story and allow us to confront the debate on our own terms, just as we would if we happened to walk by Mrs. Johnson’s house mid-argument.

Short Story

1973, Alice Walker, Classic, Voice

Title of Work and its Form: The “To be, or not to be” soliloquy, poem

Author: William Shakespeare

Date of Work: 1600-ish

Where the Work Can Be Found: Act 3, Scene 1 of Hamlet. Remember, kids: we love public domain. You can find a full text of one of the versions of the play at Project Gutenberg. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/1524/pg1524.html You may find the soliloquy itself and some variations between quarto and folio versions at Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/To_be,_or_not_to_be. Go ahead, watch Kenneth Branagh deliver the soliloquy in his excellent film version: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-JD6gOrARk4

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Tone

Discussion:

At this point in the play, Hamlet is not doing very well. He knows that his father was killed by his uncle, the same man who married his mom. He’s having problems with his girlfriend (granted, he’s the cause of a lot of the problems). That darn Fortinbras is always out there, ready to attack at any time. But Hamlet has a plan. An acting company is coming to give a performance at court and Hamlet decides that the play is the thing wherein he’ll catch the conscience of the king. And once Claudius feels guilty…he’ll apologize? I don’t know. I don’t think Hamlet knew, either.

During this soliloquy, Hamlet is indeed weighing the value of his life and whether or not his struggles are worthwhile. One of the eight zillion things we can steal from the Bard is the way he really uses the iambic pentameter. In a lot of poetry (especially mine), the meter can be an obstacle. The effort to maintain meter and rhyme can lead a writer to make choices that are not motivated by artistic intention. Instead, we’re trying to figure out how to find a rhyme for “equanimity.” Adhering to meter often leads poets like me to rearrange lines to get a word into the line that is otherwise unnecessary.

Shakespeare, of course, wields the iambic pentameter with more skill than Laertes handles his sword. One way that you can tell is the length of his sentences. While there’s lots of great blank verse that consists of one-sentence lines, it can be difficult to express complicated thoughts in abbreviated sentences. I suppose you could argue with the punctuation chosen by Shakespeare and his numerous editors (such mechanics are far different now than they were then), but the longer sentences lend themselves well to an instance in which a complicated character is having complicated thoughts.

When we talk about Shakespeare, we can’t escape the awesome phrases he comes up with. We can literally steal these for use as titles. Look at just a few of the works that have gotten their titles just from this soliloquy:

- To Be or Not To Be – lots of movies, including the Mel Brooks film

- Slings and Arrows – A British sitcom about a theater company

- Outrageous Fortune – The Bette Midler movie from the 1980s

- Perchance to Dream – A Twilight Zone episode

- There’s the Rub – A Gilmore Girls episode

- What Dreams May Come – The Robin Williams movie

- The Insolence of Office - A Star Trek novel (actually, lots of Star Trek novels are named for Hamlet)

- Quietus – The name for the suicide drug in the film Children of Men (it’s not the title of the film, but I think it still counts)

- The Undiscovered Country – The subtitle of the sixth Star Trek film

- All My Sins Remembered – An episode of Andromeda

You get the idea. There are advantages when we steal a title from a great work. People who recognize the reference will take some of their understanding of the original work and apply it to yours. Unfortunately, this can also work against you. What would have happened if Tom Wolfe had written The Right Stuff in 1989? Thousands of teenage girls would have bought it and been disappointed because the book has nothing to do with New Kids on the Block or their hit song “(You Got It) The Right Stuff.”

What Should We Steal?:

- Ensure that the restrictions of a genre don’t force us into too many bad choices. Just because you’re writing in iambic pentameter doesn’t mean that you should be restricted to short sentences that happen to fit the formula.

- Titles are fair game and can lend additional weight to whatever you’re writing. Titles are often hard to come up with and pinching one from writing you admire can be a good solution, even if it’s a temporary one.

Play, Poem

1600, Blank Verse, Classic, Hamlet, Soliloquy, tone, William Shakespeare

Title of Work and its Form: Passing, novel

Author: Nella Larsen

Date of Work: 1929

Where the Work Can Be Found: The book is a classic and can be found at secondhand bookstores everywhere, including Half Price Books, a very cool chain that boasts a ton of retail locations.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Epigraphs

Discussion:

Here’s another of my literary confessions: I didn’t read epigraphs until I was well into my twenties. I’m not really sure why; I just skipped ahead to the beginning of the story. After all, that’s what I wanted to read in the first place, right? As with so many other things from my early- to mid-twenties, I was wrong wrong wrong.

Epigraphs are the literary equivalent of the amuse-bouche: a small taste of the greatness that you are about to experience. Sometimes the epigraph will reflect the themes of the larger work, sometimes the epigraph will simply start you on the journey of entering the world the writer has created for you. Each chapter of Stephen King’s The Long Walk, for example, begins with a quote from a different game show; it’s chilling when you think about it. An epigraph can also link you work to one of its spiritual brethren. Quoting Jack Kerouac at the beginning of your book indicates that your work might be a little “Beat” and suggests to the reader that your book probably doesn’t take place in an Edwardian manor house. (Although you never know for sure.)

Passing is one of my favorite books from undergrad. The book is about the relationship between Clare and Irene, two relatively light-skinned African-American women. Although they were very close as children, they drifted apart. Clare ended up living in the “white” world, even marrying a racist white man. Irene, though she could have “passed,” instead married a black man. Irene and Clare have very complicated feelings about each other and their lives. The book is really short and I don’t want to ruin the awesome ending, so just read the book.

The epigraph is taken from “Heritage,” a poem by Countee Cullen:

One three centuries removed

From the scenes his fathers loved,

Spicy grove, cinnamon tree,

What is Africa to me?

What does this mean? It seems to me that the poem is from the African-American perspective. Africans were first brought to the West in the early seventeenth century, three hundred years (give or take) before the poem was written. In the very sad centuries in which slavery was legal in the United States, African-American culture evolved in the face of terrible oppression. At what point did “Africans” become “African-Americans?”

The point is one of identity formation. People inherently decide for themselves how they wish to be seen and to be treated. Some folks care very deeply about the heritage of their ancestors and see themselves as an extended part of that lineage; others do not. To a large extent, it’s all up to the individual. If a person with dark skin has an Irish heritage and wants to be considered Irish, most of us would simply shrug our shoulders and say, “Whatever you like, friend. Top of the morning to you.” Still, others would object. This is the dilemma that Clare and Irene are facing in the novel. Clare has said, “What is Africa to me?” She has disavowed her African side and claimed all of the privileges that being white offered at the time. Irene has done the exact opposite. The situation and the epigraph lead to a million questions: Did Clare do the wrong thing? Does Irene resent Clare for the way their lives have diverged? Is Clare any different in the “white” world than in the “black” world? Was Clare’s husband deceived in any way? What does race really mean about us? To what extent can we shape our own lives? What pull does our ancestry have on us? How big a pull should it have?

I could go on. In four short lines, Larsen prepares the reader for the complicated dilemma that follows.

What Should We Steal?

- Manipulate the reader’s expectations with a meaningful epigraph. You prime a lawn mower by shooting a little gasoline into the carburetor (or something). After that, your engine is ready to run. It’s the same thing with an epigraph. You jump-start the reader’s brain and prepare them for what follows.

- Establish tone with your epigraph. The four lines from Countee Cullen’s poem are poetic and playful at the same time, just like Larsen’s book. If you have trouble figuring out the first few lines, the last one is very clear; the same is true with Passing. You may not GET everything the first time, but there will be something that does tickle your intellect.

Novel

1929, Classic, Epigraphs, Nella Larsen