Why’d You Do That, Jim Ruland?

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Jim Ruland is a very interesting man. Not only does he write about music and books, but he’s one of those people who manage to do a little bit of everything and to do them all well. Of greatest note to me is his fun aesthetic, both in the work he produces and the forms in which he produces. If you take a look at his web site and his Tumblr page, you’ll see that he loves to experiment with visuals and narrative form, while still fulfilling his fundamental duty to tell a story and to entertain.

Sure, you might want to know about how Mr. Ruland articulates his overall philosophy regarding fiction. You may want to read a 10,000-word essay in which he writes in great detail what makes a story interesting to him. Well, look elsewhere for those things. (The gentleman has appeared on at least one podcast.) I’m really curious about some of the small choices Mr. Ruland made while writing Forest of Fortune.

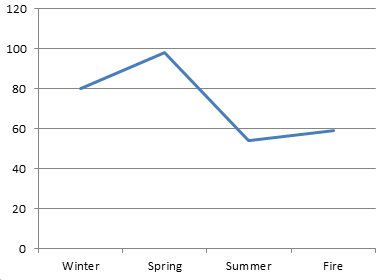

1) So the book is split up into four sections: Winter (79 pages), Spring (97 pages), Summer (53 pages), Fire (58 pages). I think I get why the last section isn’t named for a season. Here’s what I want to know: How come the second section is the longest? Why are the last sections shorter than the first two when there are so many conflicts to resolve?

JR: That’s weird! I didn’t notice that. I would have guessed the shape was more like a funnel: wide at the top and narrow at the bottom. I’m not sure what shape this is. Some kind of exotic bong? Forest of Fortune tells the story of Alice, Pemberton and Lupita and we get to know these characters through their own point of view. What I found is that with three principal characters there’s a lot of scenes to be set, personal histories to populate, worlds to be built, etc. But as the story approaches its climax, the storylines converge. Plus, I wanted the end to be the best part of the book (like The Hangover) (kidding/not kidding) so that it’s a rewarding experience for those who stick with the book to the last very page.

2) At the beginning of the book, Pemberton is running away and drowning in drink. Lupita has a bit of a gambling problem and is adrift in her life. Alice has a neurological setback influenced by her personal problems. How’d you deal with having three parallel protagonists who aren’t exactly as active and dynamic as James Bond or as shallow as a character on a TV sitcom?

JR: I don’t remember where I got it, but at some point I picked up the advice that one should construct characters as if they were going to be played by brilliant actors and actresses. In other words, there are no bullshit characters with throwaway lines. Give every character great scenes and memorable dialogue. In early versions, it was clearly Alice’s book (at least in my mind, anyway). Then for a while it was Pemberton’s. But I discovered that it didn’t really matter which character I intended to make “the main character” as each reader chooses his or her own.

3) Each section of the book is divided into brief chapters. I’m guessing that one reason you did this was to help the reader negotiate the transition between focal characters. But sometimes you have two sections in a row that focus upon the same focal character. Why’d you do that?

JR: Yes, I kept the chapters short because I didn’t want the reader to “forget” about a character. Sometimes I had to double up on a particular character for fairly mundane reasons: they keep different hours. Pemberton works at the casino during the day while Alice works the graveyard shift and Lupe comes and goes as she pleases.

4) Pemberton’s unpleasant boss, O’Nan, uses a beautiful gold Montblanc fountain pen filled with a cartridge of red ink. Why’d you choose to put that pen in his hand?

JR: One of the things I learned as a teaching assistant was to avoid using red pens when marking up student work. This advice even came with the slogan: “Don’t bleed on the page.” O’Nan is the kind of guy who not only enjoys bleeding on the page, he desires to do so with style, hence the Montblanc. I didn’t realize until very recently that fountain pens were objects of intense interest to their collectors. If I had known, I might have chosen a pen “worthy” of O’Nan’s low character.

5) Each section of the book begins with an italicized fraction of a first-person narrative unspooled by, shall we say, an important character. What do you want writers to think the first time they read the italicized section before going into dozens of pages of third-person prose?

JR: I don’t want to say too much about these sections because they are very important to the framing of the story and impact the way the reader perceives it. Suffice to say I want readers to be aware that there is a historical context that may or may not antagonize preconceived notions about the inhabitants of early California. Hopefully, the reader’s understanding evolves as he or she move through the novel’s four seasons. I had neither an agent nor a publisher when I finished Forest of Fortune and I worried that these sections would come under fire at some point, but I’m happy to say that never happened.

6) So the reader doesn’t have to be Sylvia Browne to guess that the lives of the three focal characters will intersect and that intersection will be centered around the Forest of Fortune in some way. But check it out: Pemberton’s story literally ends in close proximity to the Forest of Fortune. Alice’s story literally ends in close proximity to the Forest of Fortune. Lupita’s story ends figuratively in close proximity to the Forest of Fortune. How come?

JR: Forest of Fortune is both a place within the casino and a fantasy. When I worked at an Indian casino, the names of the various establishments were a source of great amusement. For instance, we actually had a Dreamcatcher Lounge, as hokey as that sounds. My employment coincided with the recession, so I felt bound to the place. I wanted to leave, but felt like I couldn’t afford to quit. This feeling intensified when I went into recovery for alcoholism. I wanted to find a healthier place to build a new life for myself, but I was stuck at the casino. I felt trapped there. It was a feeling that was shared by many of my coworkers and this feeling is a big part of the book. Of course, it was only a feeling. I could have left anytime, but I didn’t. I stayed way too long.

7) The word “lonely” appears a number of times in the book. The three protagonists all seem pretty separated from themselves and from those around them. What are you trying to tell us about your characters? But each of these somewhat passive characters has a confidante. Were you consciously trying to put a mirror up to each of them so you could release characterization and exposition? Were you thinking something else?

JR: To be caught in the grip of an unhealthy experience – whether it’s drug abuse, medical issues, the inability to move on from a relationship, etc. – is extremely isolating. Indian casinos are almost always located in out-of-the-way places, so these places are geographically remote as well. These factors contribute to a species of loneliness that just feels lonelier than other kinds of isolation. It’s not that the characters are passive: they’ve succumbed to forces greater than they are, i.e. addiction, epilepsy, etc. The confidantes are necessary to shake the protagonists out of their way of seeing the world and coerce them into action. In other words, make things happen. Also, and we haven’t touched on this, but the book isn’t all darkness and squalor. There’s a good bit of humor, and that’s a lot easier to pull off when you have two or more characters who are with intimate with one another’s shortcomings.

[Editor’s Note: Aw, I certainly didn’t intend to imply, dear reader, that Forest of Fortune is all “darkness and squalor.” There are many laughs in the book and some scenes that are indeed quite light-hearted. I love Pemberton’s encounter with a conceited former colleague and his scenes with a friend who is also his dealer. There’s a lot of dark humor in Alice’s plight, both in terms of her health problems and her living situation.]

8) Okay, so the principle of Chekhov’s Gun mandated that one of the characters wins the Forest of Fortune jackpot. That’s a given. Here’s the thing: the actual winning of the jackpot occupies about a third of a page. And you seem to zoom through the jackpot to get to what happens after. Why’d your third person narrator go the speed that it did?

JR: One thing that recovery has taught me is that the key to a healthy, happy life is to live in the moment. Don’t dwell on the past or obsess over the future. Be where you are. Casinos antagonize this idea. They are all about suspending the present for the promise of a more rewarding future. Vegas takes this a step further: You can be someone else. Go ahead. We won’t tell. What happens here stays here. When you’re trying to separate someone from their money, you don’t want them to dwell on the consequences of their actions.

9) There are some REALLY pretty and powerful images in the book:

“As Lupita labored up the grade, she wondered why some mountains out here on the outskirts of the desert were jacketed in soil while others resembled piles of boulders stacked by a gigantic hand. Not for the first time she wondered how two mountains could be the same height and shape, but so different. One covered in verdant scrub, the other rocky and barren. They sat side-by-side, inviting comparison. Similar but different, like Lupita and Mariana.”

“Maybe O’Nan was taunting him because being here was like pressing up against the window of his former life: Pemberton could look all he wanted but he couldn’t quit grasp what he once had.”

“…a hawk alighted on the picnic table in her backyard, a jackrabbit twitching in its talons. Lupita watched in horror as the hawk tore the thing to pieces. To be in love is to be tormented: you’re either the rabbit or the hawk.”

I have my own book that I’m trying to make good, so I gotta know: How’d you come up with such potent images that are so closely connected to character?

JR: Thank you. For this project, I really focused on the characters. I love story stories. A desire to know what’s going to happen next is what drives me as a reader or filmgoer or TV watcher. Once I’ve got the story down, I can think about other things that are going on, the creative choices being made. My first attempts at novels were marred by a fixation on scenarios in which characters were neatly slotted into their roles. For Forest of Fortune I spent a lot of time thinking about how the individual characters see the world. I think it helped that all of the characters spend most of their time in the same place. Of course, they’re going to see it differently!

10) I love the cover art for Forest of Fortune. Slot machine? Check. Your name and the book’s title in casino-ey neon? Check. The image of the slot machine is askew and slightly scrambled? Makes sense. Three visible reels instead of the five described in the book? Stop being stupid, Great Writers Steal guy. If there were five reels in the image, each would be too tiny. Who are you to criticize? What have you ever done? Okay, geez, me. Hit myself in the Vital Lie, why don’t you?

Here’s my question: Like I said, I love the cover art. I am interested in the way the art and book are related. I read Forest of Fortune as a fairly straight “literary” novel, whatever that means. The cover art seems like it wouldn’t be out of place on a book with even more supernatural/mystery elements. (The book seems especially mystery-y around page 118, when your narrator seems to suggest that the Forest of Fortune may be cursed.) If you had a magic bookstore wand and could put the novel in any department you like, real or imagined, what would it be?

JR: Thanks, I’m a big fan of the cover, too. The designer, Sylvia McArdle, did an excellent job. It’s a concept I presented to my publisher and I couldn’t be happier with the result, but if you like the cover then you’ll really like this:

I’ve always been drawn to genre fiction, weird stories, work that hybridizes established modes of writing. On one hand, Forest of Fortune is a work of fiction that cozies up to the supernatural, collides with crime and is shrouded in a bona fide mystery. One the other hand, it’s a deeply personal novel that draws on my experience of hitting bottom while working at an Indian casino. I like to call it my autobiographical ghost story. I worried about this up until last summer when I read Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 and saw that it was possible to make high art out of low culture. I’m not comparing myself to Bolaño, but it eased my anxiety over whether or not there is a name for what I’m doing.

As for where I’d like Forest of Fortune to be shelved, that’s easy: I’d want it to hang out with the bestsellers.

Jim Ruland is a Navy veteran, former Indian casino employee, and author of the short story collection Big Lonesome. He is the host of Vermin on the Mount, an irreverent reading series based in Southern California. He is a columnist for the indie music zine Razorcake and writes The Floating Library, a books column, for San Diego CityBeat. His work has been published in The Believer, Esquire, Hobart, Granta, Los Angeles Times, McSweeney’s, Oxford American and elsewhere. Ruland’s awards include a fellowship from the NEA and he was the winner of the 2012 Reader’s Digest Life Story Contest. In April 2014, Lyons Press will publish Giving the Finger, co-written with Scott Campbell, Jr. of Discovery Channel’s Deadliest Catch. He lives in San Diego with his wife, visual artist Nuvia Crisol Guerra.

Forest of Fortune, Jim Ruland, Tyrus Books, Why'd You Do That?

What do we notice? “Spring” is the longest section and the final two are much shorter than the others. Why does this make sense? In “Winter” and “Spring,” Mr. Ruland has a lot of pipe to lay so the end of the narrative will flow. Further, once we get to the climax, we (as readers) just want to go go go and Mr. Ruland shrewdly gives us what we want.

What do we notice? “Spring” is the longest section and the final two are much shorter than the others. Why does this make sense? In “Winter” and “Spring,” Mr. Ruland has a lot of pipe to lay so the end of the narrative will flow. Further, once we get to the climax, we (as readers) just want to go go go and Mr. Ruland shrewdly gives us what we want.