Show Notes:

Enjoy this interview with George Williams, author of The Valley of Happiness, a collection published by the fine people at Raw Dog Screaming Press.

Take a look at Mr. Williams’s Goodreads page:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/4875077.George_Williams

Order your copies of his Raw Dog Screaming books from the publisher:

http://rawdogscreaming.com/authors/george-williams/

Here is a text interview Mr. Williams granted to D. Harlan Williams:

http://www.dharlanwilson.com/dreampeople/issue35/interviewwilliams.html

Mr. Williams refers to a book about the Shakespeare Authorship question. He’s talking about James Shapiro’s excellent book, Contested Will:

http://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/mar/20/contested-will-who-wrote-shakespeare

Here’s “The Magpie on the Gallows,” the painting that Mr. Williams chose for the cover of his collection:

Like writing exercises? Here is one inspired by the conversation I had with Mr. Williams:

http://www.greatwriterssteal.com/2015/01/02/an-exercise-inspired-by-george-williams-author-of-the-valley-of-happiness/

Visit my website: http://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Like me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Follow me on Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Many thanks to the Library of Congress for their beautiful public domain images:

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2012649048/ (Savannah during the Civil War era!)

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/fsa1998006340/PP/ (Voters in 1940 North Carolina waiting to cast their ballots!)

Short Story Collection

2014, George Williams, Raw Dog Screaming

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Katherine Riegel is a friendly woman and a good teacher. She’s also a co-editor at Sweet: A Literary Confection. Most of all, however, Ms. Riegel is a writer who loves creating poetry and creative nonfiction.

In November of 2014, Ms. Riegel published a powerful piece of creative nonfiction at Brevity. Go ahead; check out “Run Towards Each Other.” Then come back here and see why the author did what she did.

1) You begin “Run Towards Each Other” with the following two sentences:

“It is Thanksgiving, again. My smile is a weapon cutting off access to my grief-treasure.”

So…”grief-treasure” isn’t a real word. I even copied it into Microsoft Word to make sure. Then I looked on dictionary.com. Then I realized you must have made it up for some reason.

How did you decide to combine those two specific words? Why did you include the hyphen?

KR: Such an interesting question! I deliberately wanted to link those words in order to make sure the metaphor was clear. I imagined the smile/weapon protecting treasure—something precious, something coveted, something collected over time. So a stranger might see only the weapon, the defense—the smile. But the treasure being protected is actually grief. So it was layers of metaphor: smile=weapon, grief=treasure. In asking the reader to engage with complex metaphor, I didn’t want language itself to make understanding any more difficult. So I…bent language to make it do what I wanted. And I think the comparison of grief to treasure in particular is so unexpected, so out of the norm in terms of the ways we usually talk about grief, that I didn’t want the reader to be able to interpret it any other way.

2) The third paragraph is all one sentence. And there are en-dashes that split the sentence into three sections in addition to commas and everything else that makes up a sentence.

Why did you decide to combine all of those clauses? How did you make sure that the reader would know what you meant to say? What was the effect you hoped to create?

KR: Microsoft Word wasn’t happy with that sentence. (Though actually the 3rd paragraph is 2 two sentences, which itself is problematic because the 2nd “sentence” is technically two fragments separated by a dash.) In the first sentence of that paragraph, the dashes did what dashes are generally supposed to do, in that, if you took out the material inside the dash, the grammatical structure of the sentence, and its essential meaning, would be unaffected. Oh, and incidentally those were em dashes in my document; I think the formatting of the site turned them into en dashes. I wanted to put some description of my own smile into the piece, but I knew if I didn’t limit it that I could go on and on in the most unflattering ways about my own smile. This made it essential to keep the image short, tucked within a sentence. I also deliberately left out the “and” before “my new loves” because I wanted the three items in the list to be equal. Somehow adding “and” would make it feel like the last one, the “new loves,” was either more or less important than the other two. I intended the order to be more chronological than by importance.

I think also that this particular paragraph, reflecting my (the narrator’s) self after my mother’s death, is particularly fragmented. All the clauses, as you say, are both linked and separate, connected only tenuously through punctuation. The speaker, too, is just barely held together, and still doesn’t quite believe how or why she is. As for the 2nd sentence, where I get to write “me—me,” I confess I gave myself permission to do that because of some lines/line breaks in a Sharon Olds poem. It’s called “His Stillness” and the sentence reads like this:

At the

end of his life his life began

to wake in me.

She deliberately ended a line with a throwaway word—“the”—in order to get a line which begins with “end,” ends with “began,” and has “his life” repeated in the middle. I wasn’t breaking my mini-essay into lines (though I did when I first wrote it—shhh, don’t tell) but there was something really important about repeating that word “me.” The narrator doesn’t feel worthy of the support she’s gotten, so she must repeated the word “me” to persuade herself she matters, even as that words is followed by “insignificant.”

3) So, “toward” and “towards” are interchangeable, but “towards” has that extra Zzzzzzzzzzzz sound at the end. “Toward” has a nice, crisp consonanty ending.

Why did you use “towards?”

KR: I have to confess this may be just dialect. I grew up in Illinois with parents from DC and Pennsylvania who went to school in Vermont. When I take “accent quizzes,” it nearly always gets my accent wrong because of that. (I say “ca-ra-mel,” for example, not “car-mel.”) I guess, when I think about it, “towards” sounds more together-y to me. People are running towards each other—everyone is doing the action. A person would run toward a house, because the house wouldn’t be doing the action. Or maybe I’m completely full of it, and I’m a teacher, so I can come up with an answer even if I have to make it up. 🙂

4) I’m pretty sure Grammar Girl would tell you that you didn’t need that comma in the sentence, “It is Thanksgiving, again.”

How come you put that comma there?

RM: Oh, yes. Very important, and very deliberate. I wanted to emphasize “again.” It is inevitable, it keeps coming around even when you don’t want it to. Putting the comma there was to try to show the dread, to make the reader feel just how much the narrator didn’t want it to be Thanksgiving—again. Oh boy. Here we go.

5) And here’s the penultimate sentence:

“In the barn I will pull carrots out of my pockets and hold them flat on my palms.”

“In the barn” is a dependent clause that begins a sentence. All of those nerds who complain about grammar stuff might say that you shoulda put a comma after “In the barn.”What made you leave the comma out?

KR: Really interesting punctuation questions! I think language has a music to it, a rhythm. Grammar and punctuation rules are in place to help with clarity, but we all know many of them are arbitrary and some are based on the rules of Latin, which early English grammarians decided was the only “proper” language and so must be imitated. In this case, it’s clear what’s happening, and I heard the sentence in a particular way in my head. It wasn’t interrupted by a pause after “barn.” I’m one of those people who hears a voice very clearly in my head when I read; I don’t read my work aloud much during revision because it’s redundant. I heard this sentence as a whole, the image words like fence posts, regularly spaced: barn, carrots, pockets, flat, palms.

It’s odd to see how often I bend/break grammar and punctuation rules, when I emphasize clarity in both those areas as a teacher. I suppose I’m more concerned with syntax and its possibilities than with absolute rules. I want writing to be precise, in order to get across nuance and subtlety. That kind of precision requires a writer to make considered choices that sometimes break rules.

Katherine Riegel is the author of two books of poetry, What the Mouth Was Made For and Castaway. Her poems and essays have appeared in journals including Brevity, Crazyhorse, and The Rumpus. She is co-founder and poetry editor of Sweet: A Literary Confection, and teaches at the University of South Florida. Visit her at www.katherineriegel.com.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Brevity, Katherine Riegel, Sweet: A Literary Confection, Why'd You Do That?

Show Notes:

Enjoy this interview with Christy Crutchfield, author of How to Catch a Coyote, a novel published by Publishing Genius Press.

Find out more about Christy Crutchfield at her web site.

http://www.christycrutchfield.com

Order your copy of her book from her publisher:

http://www.publishinggenius.com/?p=3347

Or you can order your copy from your local indie bookstore:

http://www.indiebound.org/book/9780988750388

Or you can order the book online the old-fashioned way:

http://www.powells.com/biblio/62-9780988750388-0

Visit my website: http://www.greatwriterssteal.com

Like me on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/GreatWritersSteal

Follow me on Twitter: @GreatWritersSte

Music: “BugaBlue,” Live At Blues Alley by U.S. Army Blues is licensed under a Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

http://freemusicarchive.org/music/US_Army_Blues/Live_At_Blues_Alley/

Many thanks to the Library of Congress for their beautiful public domain image:

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/nclc.00097/

Short Story Collection

2014, Christy Crutchfield, How to Catch a Coyote, Publishing Genius Press, The Great Writers Steal Podcast

Title of Work and its Form: “”In the style of Joan Mitchell”,” poem

Author: Janelle DolRayne

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem debuted in the October 2014 issue of inter | rupture. You can find it here.

Bonuses: Here is an apt poem that was subsequently chosen for Best of the Net 2013. Here is a reading list that Ms. DolRayne put together in her capacity as Assistant Art Director for Ohio State’s The Journal. Want to see the poet read her work?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Conceits

Discussion:

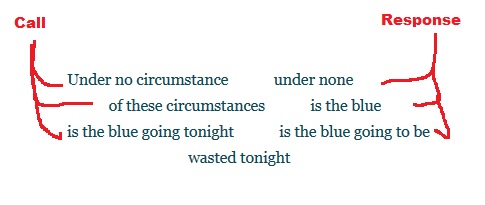

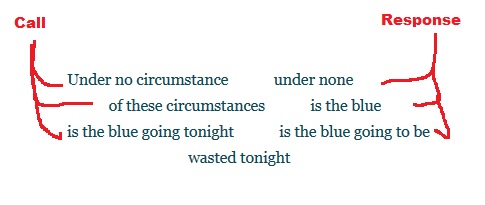

Ms. DolRayne offers us a poem with a fun and interesting conceit. (It bears mentioning that Ms. DolRayne may not have the same idea as I do about her poem…but that’s okay.) It seemed to me that the poem is a powerful attempt to use poetry to mimic the loose and quietly powerful feel of a folk song. If you’ll notice, the first few stanzas feature lines that employ the call-and-response technique popular in folk, blues and rock music:

You’ll also notice that the last stanza abandons the conceit, which is perfectly fitting. The narrator of the poem is now speaking in “unison” or “a cappella.”

You’ll also notice that the last stanza abandons the conceit, which is perfectly fitting. The narrator of the poem is now speaking in “unison” or “a cappella.”

First, I’ll give you some examples of the call and response I’m talking about. Phil Medley and Bert Berns wrote “Twist and Shout,” a song that was covered by a lot of groups, including The Beatles. You’ll notice that the background vocalists mirror and augment the lead singer.

Steven Page and Ed Robertson wrote “If I Had a Million Dollars.” As I understand it, Ed had written the bulk of the song, but only had his part of the vocal. Mr. Page heard the song in progress and added his part. Mr. Page sometimes simply repeats Mr. Robertson’s part; sometimes he adds to the narrative of the song and takes it in a new direction.

The response doesn’t even have to come from a vocalist. In George Thoroughgood’s “Bad to the Bone,” the response comes from guitar and saxophone.

I loved Ms. DolRayne’s use of this technique for a number of reasons:

- Poetry is just a kind of music, right? Why not make that connection explicit in this way? Some people think poetry is a fancy-pants thing you read because some teacher told you to. Those same people love music without realizing poetry does many of the same things.

- The “call and answer” adds another voice to the poem, even though it’s only being written by one author. In this way, we’re able to produce a kind of harmony.

- The images and ideas in the poem are reinforced through repetition and through being conceptualized in a different way.

- The phrases on each side of the large spaces can be considered poems unto themselves and these poems are in conversation with each other, aren’t they?

One of the inherent difficulties in writing is bridging the gap between thought and the written word…and trying to figure out how to combine words, space and punctuation in such a way that the reader will understand the thought you had. Ms. DolRayne literally adds in the pauses that led me to treat her poem like a kind of song. For the poet, those pauses are spaces between words. For a singer, those pauses are bits of silence between musical phrases. Why not take Ms. DolRayne’s idea and try to lay down some prose in the style of a musician?

I think one of the reasons that I identified the call-and-answer conceit in the poem is because the poem was challenging me, inviting me to make sense of it in a way that made me happy. If you’re near a window, look out at the clouds. What shapes you do see? A phenomenon called “pareidolia” forces us to make sense out of “vague or random” stimuli.

Now, that’s not to say that Ms. DolRayne has given us a poem filled with randomness, because she didn’t. That’s writing craft in a nutshell, folks. The poet had to work very hard to create a work that clearly communicated her own thoughts while ensuring the piece was open enough to allow the reader to draw his or her own conclusions.

Unfortunately, there’s no easy method by which writers can learn to be simultaneously specific and vague. That’s just not something you can learn with a step-by-step procedure. Instead, we just need to read a lot of poems and write a lot of poems and hope that our skills improve to the point where we have the power to turn any trick we like.

What Should We Steal?

- Think of yourself as a songwriter when you compose. The conventions of music are not exactly the same as the ones writers use, but we can use their prose equivalents to our advantage.

- Trigger your reader’s pareidolia. How can you get your reader to see the plan in what seems like randomness?

Poem

2014, Conceits, inter|rupture, Janelle DolRayne, Ohio State

Title of Work and its Form: “Buckle Up,” short story

Author: Matt Carmichael (on Twitter @mttcarmichael)

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the September issue of Bartleby Snopes. You can read the story here.

Bonuses: Here is a story Mr. Carmichael published in The Adirondack Review. The gentleman has also done great work as the managing editor of TriQuarterly, a great journal.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Settings

Discussion:

This is the story of the lengths to which a parent (a father, in this case) will go to ensure their kids have happy Holidays and believe in the magic the world can possess. The first person narrator of the story has an important and morbid job: he tallies the traffic deaths for the year so the number can be displayed on the Highway Department’s roadside signs. The gentleman seems to enjoy his work, as work goes, and he is looking forward to the office holiday party. Bren, the narrator’s coworker, dresses up like Santa Claus to impress his son Tony, for whom this may be the last believing-in-Santa Christmas. Saint Nick eats cookies, right? Well, Santa Bren is offered some treats that contains peanut butter. Bren is allergic, but eats a cookie anyway, so as not to disappoint Tony. The ensuing heart attack puts a damper on the party, but the narrator concludes the story by pointing out that he lost the office traffic death pool and that Bren should be fine soon, as “heart attacks heal quick.”

What a morbidly funny story! Mr. Carmichael ensures that the piece’s structure is quite solid. The first aspect of the story on which I’d like to focus is that “Buckle Up” takes place in a workplace. The great Lee K. Abbott once pointed out to those of us who were in his class that there aren’t as many “work” stories as you might think there would be. After all, people spend more than a third of their lives at or on their way to work. Why wouldn’t we have a higher proportion of stories in those settings? Well, Mr. Carmichael makes the setting of the story seem as simultaneously dreary and pregnant with drama as you might expect from your own work experiences.

Let’s play advocatus diaboli for a moment. What if Mr. Carmichael made the wrong choice; what if he should have told another of the narrator’s stories? One that was more his own? The narrator certainly has his own life going on; a decent job, he likes Mountain Dew, he can string together fun sentences…why not send him on his own adventure instead of forcing him to describe what is probably Bren’s story? Well, Mr. Carmichael can always write more stories about the guy if he wants to do so. Further, the narrator seemed to be to be fairly passive and maybe even adrift in his own life, anyway. Why not let that kind of person tell the kind of story with which he’s more comfortable?

Because the author adheres strongly to “traditional” story structure, there’s a defined climax of the story: Poor Santa Bren has eaten a whole peanut butter cookie and is having a bad reaction and a heart attack. Then:

“Ho, ho, ho,” says Bren. He’s gasping for air. “This Christmas, Santa wants an epinephrine pen.”

He stands up and then keels over onto the floor. Francis yells, “buckle up, people, this is the real deal” and calls 9-1-1. Bren’s wife runs to his desk and ravages through his drawers. She says she thinks he keeps one of those pens at work.

What is Mr. Carmichael doing with the climax of his story? Why, he has set up a comic setpiece! Shakespeare did it, giving Will Kempe the fun and funny role of Dogberry in Much Ado About Nothing. You’ll find the same principle in a ton of comedy films.

John Belushi has less screen time in Animal House than you would have thought. Ramis, Kenney, Miller and Landis, however, are smart enough to let Belushi dominate the moments of BIG comedy in the film. For example:

The 40-Year-Old Virgin is a comparatively quiet comedy film…until Steve Carell’s character is given a big comic setpiece:

Mel Brooks allows the whole narrative of Spaceballs to percolate until the big climax of the film, as all of the characters are trying to escape from the Mega Maid. With all of that storytelling pipe laid, the fantastic Mr. Brooks can let the physical comedy fly:

I guess what I’m saying is that I admire that Mr. Carmichael put a physical comedy setpiece into his short story; that’s not something you see every day. (But maybe it should be!) We chuckle as we finish “Buckle Up,” imagining Santa Bren gripping his itchy neck and flailing about as his wife tries to pull back his red pants to expose enough skin for the injection he needs.

What Should We Steal?

- Set a story or poem at work. Work may not be your favorite place, but the situations you experience there are pretty universal and audience-friendly.

- Cast a comic setpiece in prose. Why can’t a short story be as funny as a Saturday Night Live sketch?

Short Story

2014, Bartleby Snopes, Lee K. Abbott, Matt Carmichael, Santa Claus, Settings, TriQuarterly

Title of Work and its Form: “Islanders,” short story

Author: Kate Folk (on Twitter @katefolk)

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the Spring & Summer 2014 issue of PINBALL. You can read the piece here.

Bonuses: Here is a short short story Ms. Folk published in Neon. Whoa…Ms. Folk had the honor of interviewing Joyce Carol Oates by e-mail. Here‘s how she and her colleagues rose to the challenge of asking Ms. Oates interesting questions that she hadn’t heard a million times. Want to see Ms. Folk read her work?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Stakes

Discussion:

This epistolary story relates the sad tale of an unnamed man who is still in love with Bonnie, the wife who apparently left him to throw herself into the arms of a “jobless artist.” Through the course of nine e-mails, we learn that the narrator is in the middle of a tense diplomatic situation; an island off the coast of a “strategic coastal sardine town” is drifting into the sea. There are two narratives here: the story of the conflict between islanders and mainlanders and that of the narrator’s seemingly futile attempt to work things out with Bonnie.

I love the efficient way in which Ms. Folk establishes the parallel narratives. The very first sentence introduces the personal conflict:

Don’t know if you’ll even read this email, as you are probably busy fucking your artist lover who has all the time in the world to spend with you due to having no actual job and leading the artistic lifestyle you always wanted for yourself…

The second paragraph establishes the crucial external conflict:

Supervisor Ross has sent me to this strategic coastal sardine town Re: Island Drifting Irretrievably to Sea. Tiny man-made island has floated a half mile off the coast for decades. In recent months, it has appeared more distant.

While this story isn’t a pure short-short, it’s still fairly brief; the author wastes no time establishing the situation and the inherent stakes involved. The narrator is coping with the painful loss of his wife and wants her back and a coastal community has been torn apart. We are more likely to care about these problems because Ms. Folk makes them clear from the beginning.

As I read the story, I wasn’t expecting to learn the name of the protagonist’s ex-wife. After all, how often do we use our significant others’ names when we write them e-mails? I did, however, love the way that Ms. Folk slipped her name into the story. The penultimate e-mail, sadly, was written while the narrator was drunk and particularly lovesick. He lies about being under siege, trying to convince his ex-wife that his life is in danger in hopes that the prospect of losing him will change her mind about the jobless artist. Dissembling, he leaves his ex-wife with these words:

My one true love, my beautiful, sweet Bonnie!

What a graceful and natural way to slip Bonnie’s name into the narrative! We never learn his name; learning hers personalizes her and helps us understand how he really feels. Further, when we know someone’s name, we naturally feel closer to them. In this way, Ms. Folk simulates adding some of Bonnie’s voice to the story. Sure, the narrator probably did some crummy things, and we’re not happy that she seems to have taken up with the kind of slimy loser of whom we were jealous in high school (and college and after college). “Bonnie” humanizes the character very quickly.

You already understand the principle if you remember The Silence of the Lambs. (A must-see film.) Remember when Clarice and her Quantico friend, Ardelia Mapp, are watching the press conference in which the Senator asks the then-unknown kidnapper to return her daughter?

SEN. MARTIN

I’m speaking now to the person who is holding my daughter. Her name is

Catherine… You have the power to let Catherine go, unharmed. She’s

very gentle and kind - talk to her and you’ll see. Her name is

Catherine…

Clarice is moved by what she sees. Other trainees are all around her.

CLARICE

(whispers)

Boy, is that smart…

ARDELIA

Why does she keep repeating the name?

CLARICE

Somebody’s coaching her… They’re trying to make him see Catherine as a person - not just an object.

Ms. Folk’s story is certainly very different from that of Thomas Harris and Ted Tally, but all three writers make great gains by using the simple release of a name to create powerful characterization.

What Should We Steal?

- Establish conflicts clearly, particularly in shorter pieces. If you’re writing an epic novel, you have a little bit of time before you risk losing the reader’s attention. Front-loading the conflicts and the stakes they create can immerse us in your piece very clearly.

- Name an otherwise tangential character to humanize him or her. What sets us apart from others more completely than a name?

Short Story

2014, Epistolary, Kate Folk, PINBALL, Stakes

Title of Work and its Form: “Coming to the Table,” creative nonfiction

Author: Allegra Hyde

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece made its debut in Flyway: Journal of Writing & Environment. You can find the piece here.

Bonuses: Try not to be jealous; here‘s a short piece Ms. Hyde placed in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. Here is a brief interview Ms. Hyde gave to introduce herself as an editor for Hayden’s Ferry Review. Here is a short story she published in Superstition Review.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Beginnings

Discussion:

Ms. Hyde describes what must have been a fascinating time in her life. She was a first-year teacher in Eleuthera, “a skinny Bahamian out-island that dangles like a fishhook towards the Caribbean.” And she didn’t know how to cook. Her students at The Island School were very privileged, indded. Not only were they matriculating in what must be a breathtakingly beautiful place, but they were children of parents with means. One day, she and her students decide to cook a community meal sourced entirely from Eleutheran food. There were a couple hitches along the way-not the least of which was Ms. Hyde’s lack of confidence in her cooking ability-but students and staff alike enjoyed cassava-banana bread, fruit salad and pumpkin soup that contained just a hint of coconut.

I am sad to admit that I did not know about Eleuthera before reading the piece. I am well aware of where The Bahamas are located, but I hadn’t realized to which island Ms. Hyde was referring. Here’s the map extract from Wikipedia to orient us:

I think it’s pretty clear that Ms. Hyde’s first movement in the piece is an extremely important one. What’s her entry point into the story? A brief paragraph set apart from the rest of the narrative by

I think it’s pretty clear that Ms. Hyde’s first movement in the piece is an extremely important one. What’s her entry point into the story? A brief paragraph set apart from the rest of the narrative by

double spaces:

This is the situation: I am a first year teacher. I am a first year teacher at a remote environmental leadership school on the southern tip of Eleuthera, a skinny Bahamian out-island that dangles like a fishhook towards the Caribbean. I do not know how to cook.

What does Ms. Hyde gain by opening her story thus? She could easily have started off with a variation of her second paragraph:

Arriving at The Island School in 2010, I knew there would be challenges. Sunburns. The occasional jellyfish sting. Dormitory duty. But this all seemed like background noise given the opportunity I had to help students re-examine their relationship with the environment, to use the school’s own operations – which showcased methods of green living from solar hot water to biodiesel vans – as a model for inspiring a more sustainable future.

So why begin with that example of extreme narrative intrusion?

- It’s a great icebreaker and introduction. Ms. Hyde is not yet a big-time author whose accomplishments are known to the vast majority of readers. (This state could easily change, of course!) This first paragraph tells us all we need to know about Ms. Hyde to enjoy the story and does so very efficiently.

- The first paragraph is very inviting; the diction makes us feel as though Ms. Hyde is standing before us at a cocktail party, telling us an interesting and heartwarming tale.

- The complication is introduced immediately: the author claims she can’t cook…this is a story about how she took on the responsibility of coordinating and cooking a big meal.

- The setting is introduced very quickly and we’re transported to a place we’ve likely never been.

So why not begin in such a manner? Ms. Hyde seems to enjoy these “buttons,” these interjections that are given their own paragraphs. She employs the technique a few times through the course of the piece, including:

- “I never guessed that my culinary limitations would be a hurdle. I was a teacher, not a chef.”

- “It was against this backdrop that the campaign for One Local Meal began.”

While many of these interjections could simply be appended to the paragraphs that precede them, Ms. Hyde amps up the humor and reinforces the strength of her thought in these places. Most of all, it’s important to remember that we have a narrator for a reason. (Even when we’re writing about ourselves in the first person.) It’s the narrator’s job to keep the story humming and to contrive sentences in words in such a manner that we pay attention and understand.

I must say that I found one of Ms. Hyde’s choices very interesting. Her students themselves are not named or described outside of simple markers: “a glossy-haired girl.” When the author introduces local farmers and experts in Eleutheran flora, she gives them names and backstories. Now, Ms. Hyde could simply be protecting the identities of her students. That would be just fine by me. But I like to think that these choices help the reader understand what and who are most important; sure, the students are learning and enjoying a great meal. The “lower-class” characters, however, are much more interesting in the context of this piece. I loved meeting Monica Miller, a local farmer and Elidieu Joseph, an immigrant stonemason who knows best how to put wild Eleutheran plants on the plate.

The point is that we need to understand that we can’t inject every bit of knowledge we would like about the world we’re creating. Instead, we must tell the reader what they need to know in order to enjoy the greatest emotional impact.

What Should We Steal?

- Empower your narrator to do its job. It can be hard to decide where to begin a piece and where to put our sentences so that they have maximum effect…but that’s why you have a narrator.

- Offer more and deeper descriptions of the characters who are most important to the narrative. I’m finishing up a Young Adult novel (hopefully). I can’t devote pages of backstory to EVERY character…I need to tell the reader what they need to know about each of my creations.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Allegra Hyde, Beginnings, Eleuthera, Flyway: Journal of Writing & Environment

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Ravi Mangla is a very successful gent. In addition to his Outpost19 book, Understudies, Mr. Mangla has placed his work in some very cool journals, including Mid-American Review, American Short Fiction and Wigleaf. He’s also written for BULL Men’s Fiction, a personal favorite of mine.

Now, we could be overwhelmingly jealous of Mr. Mangla, but jealousy is an emotion suitable only for country songs. It would be far more profitable for us to enjoy his work and to try and learn from what he does well. You may wish to share a nine-hour phone call with him in which you ask only one question and expect him to answer. But if Mr. Mangla offered such a service, he would have no time to write! Instead, Mr. Mangla has been gracious enough to offer his insight into some of the small decisions he made in “Feats of Strength,” a short short he published in Tin House‘s Open Bar blog.

1) “Feats of Strength” features two lines of dialogue. One happens in present tense-the strongman commits to buying the car-and one happens in the past: Natalie wonders how she and her husband could have been so negligent as to purchase a defective baby crib.

Why did you put the spoken lines into italics instead of using the good, old-fashioned quotation marks? How come you did the same thing for both lines of dialogue, seeing as how one took place in the past and the other took place in the present?

RM: Dialogue is a bit of a spoiled brat, demanding not only distinctive markings but an entirely new paragraph (soon it will be asking to be underlined). Aesthetically, I don’t find the appearance of quotation marks particularly pleasing. Whenever possible I use plain text or italics. Only if the clarity is compromised will I roll out the quotes.

2) About 55% into the story, you have the first person narrator tell us the name of his child:

“-his name is Dev, by the way-“

Why didn’t you just write, “my son, Dev” instead? The clause that names Dev breaks up a sentence and also seems like more obvious and brash narration than the rest of the piece. Why’d you do it that way?

RM: I hoped it would lend some naturalism to the piece. The omission of the child’s name until late in the story suggests a fallibility on the part of the narrator. In a piece like this, with a contrivance like a strongman at its center, I have to work twice as hard to keep the reader from seeing the strings. Sometimes a small disruption, a note of dissonance, can disarm the reader and help them to buy into the narrative.

3) The strongman decides to bring his new car home in an unorthodox manner. Instead of just driving it home, he gets some exercise by pulling it there instead. You tell the reader:

“With a tow hook, he attaches a thick rope to the underside of the front bumper.”

The sentence seems to be pretty simple and declarative. Why did you put the clause with the tow hook at the beginning of the sentence? Why not just write,

“He attaches a thick rope to the underside of the front bumper with a tow hook.”

RM: I chose that phrasing solely for the sake of sentence variation. The previous sentence started with he, and I was hesitant to replicate it. I don’t want the sentences to become too predictable or monotonous.

4) In the final paragraph, the family waves goodbye to the now-inconvenient automobile. You write:

“The strongman reaches a bend in the road, disappears behind a cluster of trees.”

Why’d you remove the conjunction (I’m guessing you would choose “and”) and plop in that comma?

RM: Often I’ll exclude a conjunction between clauses for rhythm. It sounds jazzier to me (but perhaps not to every reader). It’s a habit I picked up from reading Sam Lipsyte. I’m a huge admirer of his language craft. His sentences have such a unique cadence.

[Editor’s Note: Mr. Mangla makes a good point. If you’re not familiar with Sam Lipsyte’s work, why not check out this New Yorker story he wrote. Or one of his books? You get the drift.]

5) The story is bookended with appearances from “several women in the neighborhood” who sit in their yards and watch the scene. You don’t mention them elsewhere in the story and they don’t affect the narrative directly.

Space is at a premium in a short short. This story is 671 words long. Why did you devote 27 words-slightly more than 4% of the text!-to the women? What, in your mind, is their function?

RM: They exist to underscore the strangeness of the scene. If there was a strongman lifting a car in my neighborhood, I know I’d be standing around watching. I think they also help to open up the world of the story, so the scene isn’t happening in a vacuum.

Ravi Mangla is the author of the novel Understudies (Outpost19, 2013). His work has appeared in Mid-American Review, American Short Fiction, The Collagist, Gigantic, The Rumpus, Wigleaf, and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. Follow him on Twitter: @ravi_mangla.

Short Story

2014, Outpost19, Ravi Mangla, Tin House, Why'd You Do That?

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

David James Keaton is a very interesting fellow. The gentleman is very prolific and seems very cool. He loves music and crime fiction…but I’m not sure he’s such a big fan of authority figures. His aversion to them is fine by me, as it resulted in the stories presented in Fish Bites Cop! Stories to Bash Authories, a book you should certainly get into your hands and heart. Here is the entertaining manner in which Mr. Keaton explains how you can order the collection:

If you’re looking to buy it (did I already post these retailers somewhere? oh, well), here’s a link to the Comet Press website, as well as links to Barnes & Noble (for locals), Carmichael’s Bookstore (for locals), Powell’s, Indiebound, and Amazon. I listed those in order of preference. Buy it from the publisher or the real stores first, unless you need it on Kindle. Who knows where that Amazon money goes.

Ordering Mr. Keaton’s first novel is a little easier; Broken River Books has made signed hardcover copies of The Last Projector available through their web site. The book will be worth a look; one of the things I wondered while reading Fish Bites Cop! was what Mr. Keaton would do when he had a vast canvas at his disposal instead of many small ones.

Sure, you might want to know about how Mr. Keaton articulates his overall philosophy regarding fiction. You may want to read a 10,000-word essay in which he writes in great detail what makes a story interesting to him. Well, look elsewhere for those things. I’m really curious about some of the small choices that shaped the stories of Fish Bites Cop!

1) Okay, so I made a chart of Fish Bites Cop!’s table of contents as a public service. (You can never find a simple table of contents for story collections!) I also did it so I could look at stuff a little analytically.

| Title |

POV |

Number of Pages |

| Trophies |

3rd |

2 |

| Bad Hand Acting |

3rd |

8 |

| Killing Coaches |

1st |

8 |

| Schrödinger’s Rat |

1st (we) |

13 |

| Life Expectancy In A Trunk (Depends on Traffic) |

1st |

8 |

| Greenhorns |

3rd |

12 |

| Shock Collar |

3rd |

4 |

| Third Bridesmaid From The Right (or Don’t Feed The Shadow Animals) |

1st |

11 |

| Burning Down DJs |

1st |

6 |

| Shades |

3rd |

6 |

| Three Ways Without Water (or The Day Roadkill, Drunk Driving, And The Electric Chair Were Invented) |

3rd |

11 |

| Heck |

3rd |

4 |

| Do The Münster Mash |

3rd |

4 |

| Either Way It Ends With A Shovel |

3rd |

14 |

| Castrating Firemen |

1st (directed at silent interlocutor) |

5 |

| Friction Ridge (or Beguiling The Bard In Three Acts) |

Play |

14 |

| Doppelgänger Radar |

3rd |

4 |

| Queen Excluder |

3rd |

12 |

| Don’t Waste It Whistling (or Could Shoulda Woulda) |

1st (directed at silent interlocutor) |

3 |

| Three Minutes |

3rd |

3 |

| Bait Car Bruise |

1st |

3 |

| Clam Digger |

1st |

8 |

| Swatter |

1st |

8 |

| Three Abortions And A Miscarriage (A Fun “What If?”) |

3rd |

14 |

| Catching Bubble |

3rd |

3 |

| Doing Everything But Actually Doing It |

3rd |

9 |

| The Living Shit (or Mosquito Bites) |

1st |

6 |

| Warning Signs |

3rd |

3 |

| The Ball Pit (or Children Under 5 Eat Free!) |

3rd |

6 |

| Nine Cops Killed For A Goldfish Cracker |

3rd |

22 |

There are 30 stories in the book.

The longest story is 22 pages.

9 of 30 are longer than ten pages.

10 of 30 are between six and ten pages.

11 are under five pages.

How come the stories are so short? Are you influenced by the Internet-inspired growth of the popularity of short-shorts? The stories are very “idea-oriented”…are you consciously trying to get the idea out of there as quickly as possible? Your prose is fun and punchy; do you feel you need to accentuate that part of your writer’s toolbox?

DJK: Interesting! These statistics are new to me. Did you like the scary fish picture on the contents page? I like that fish. That’s what I imagine goldfish crackers look like in our bellies. Well, as far as length, a couple venues that I was submitting to did dictate length. For example, “Warning Signs” went to Shotgun Honey, which had a 700-word limit, an odd but challenging (and kinda arbitrary) number. Also, many of these shorter pieces were written when I had zero publications to my name and I thought I could somehow crack that elusive code by writing tiny flash pieces and “get my name out there.” Translation: Give fiction away for free! Instead, this mostly meant getting Word Riot rejections five or six times a day (fastest rejections ever!). And this might be kind of a boring answer, but most of the stories are as long as they wanted to be. Well, a more boring answer would actually be “as long as they need to be.” But, truthfully, some of them probably needed to be shorter. But it’s not about what they need. It’s what we need, right?

2) A lot of us have real trouble figuring out character names. Many of your protagonists are named “Jack” or “Rick.” Why do you do that for? Are you making a point about how everyone is kinda the same, regardless of names? Or do you just like that the names are short and easy to type?

DJK: You mentioned to me in an earlier conversation how Woody Allen claimed he used names like “Jack” because they are so much more efficient, and I’m totally on board with this reasoning. It’s like Jeff Goldblum in The Fly and his closet is full of the same shirts and pants and jackets – because this means he doesn’t have to expend any brainpower on unimportant things. Although, to be fair, Goldblum’s character does all his best thinking once his girlfriend buys him his first very ‘80s bomber jacket. But for me, naming a character “Jack” is also like a shortcut to not having to name someone at all. “Jack” feels like a not-name to me, not as obviously anonymous as “John,” and it sort of sounds like a verb, too, so that’s a bonus. I’m just not that interested in names. I also don’t enjoy describing characters. Not sure where the aversion comes from, but I’d number little stick figures if I could!

Also, whenever there’s a “Jack” who is a paramedic, that’s actually a tiny snippet of my upcoming novel The Last Projector. In that book, there’s just the one Jack. Well, he’s kind of a couple people, too, but that’s another story. But in Fish Bites Cop!, the Jacks are different people, unless they’re paramedics. If that makes any sense. This answer has gotten so long and thought-consuming that I’ve now reconsidered and may start using normal names again.

3) “Nine Cops Killed For A Goldfish Cracker” is a really cool story. And you do a cool thing in it. There are three big countdowns that control the progression of the story.

- Jack starts killing law enforcement officers…the title lets us know he’s going to reach nine by the end of the story.

- One of the goldfish in Jack’s bowl ate a thousand dollar bill. The fish are executed one by one in search of the prize.

- The narrator compares Jack’s journey to that of a football player making his way down the field to the end zone.

How did you make use of these countdowns in your story? How did you make sure that the “mileposts” passed quickly, but not too quickly? How did you make the countdowns seem organic instead of all contrived and stuff?

DJK: Thanks! The countdown that shaped the story the most was the deaths of the titular “nine” cops (ten, actually). By thinking of creative ways to murder them, it gave me a very convenient way to map it all out. The countdown of the dying fish was a heavy-handed parallel to the dying cops, so that countdown was supposed to be like a Star Trek mirror-universe version of what the drying fish and dying cops were going through. The yard-line countdown was added in the 11th-hour of writing, to smooth it out and to accelerate things a bit more. Once I added yard lines, the rest of the football imagery started popping up organically and things really got fun. But the deaths of the police officers were definitely the story’s engine, and not just because I knew that a reader would expect exactly nine police officer deaths as promised, and I knew I had to deliver. But it drove the story because, when I wrote it, I’d been working late hours at my former closed-captioning job, and we had short, unhealthy lunches built into our demanding captioning duties, so that countdown was also a way to get a little bit of the story done each night on my 15-minute lunch break. One little murder a day, I’d tell myself, and I’d be home free in a week! How many times have we said that to ourselves?

4) Several of the stories have alternate titles. (For example, “The Living Shit (or Mosquito Bites)”). Coming up with titles is hard for a lot of us. Why did you include some alternate titles?

Some of the titles are really descriptive and reflect what happens in the story (“Killing Coaches”) and some are a little more “fun.” What do you think is the relationship between the title and the story?

DJK: Most of the alternate titles in the collection are their original titles. “The Living Shit,” for example, was renamed “Mosquito Bites” to make it more palatable and get it published. But I always preferred the uglier title, so I switched it back. In fact, the original title of “Nine Cops Killed for a Goldfish Cracker” was “Fish Bites Cop.” But instead of adding an alternate to that already very long title, I just called the collection Fish Bites Cop instead. Problem solved! That meant the newspaper headline at the end of the story is also swapped around. Now the newspaper reads, “Fish Bites Cop!” too. Which I kind of prefer, actually. And hijacking that story title to make it the title of the book suited the collection in many unexpected ways.

But, yeah, some of the “fun” titles were titles I had kicking around that I really wanted to write a story around. Like “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel” was actually an email subject line that my friend Amanda and I passed back and forth at that captioning job whenever we were disgruntled. So that title was her idea actually. To write a story around it, I just had to think of the two “ways” that would go with it. And the question of burying someone or digging them up seemed to be the only option.

5) “Greenhorns” and “Clam Digger” are two of my favorite stories in the book. They’re also a little different from the other stories, as they feature fantasy/supernatural elements.

How come there are only a few horror-y stories in the book? The rest seem extremely hard-boiled and realistic. (Even though the stories feature “extreme” events, of course.)

DJK: When I wrote most of these stories, I was in grad school at the University of Pittsburgh, and many were sort of an affectionate raspberry to the typical MFA-style “lit” story. So I was purposefully playing with every genre I could. The fact that the vast majority also incorporated authority bashing of some kind is a mystery for a psychologist to unravel. Hopefully, a psychologist who is just starting out so that he or she is real hungry and really, really wants to get to the bottom of these things. Or maybe a recently martyred movie psychologist who will absolve me with four magic words, “It’s not your fault.”

6) You’re real good at using unexpected verbs.

In “Bad Hand Acting,” the janitor doesn’t “walk around” the mob of police. He “orbits” them.

In “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel,” the character doesn’t just “look at” or “see” a bunch of bodies in his car trunk. He “studies” the bodies and “counts” the “elbows and knees as tangled as his guts.”

In “Shades,” the narrator “drops” a dollar in a peddler’s hand, which is a lot less secure than “handing” a bill to a person.

How do you know when to use a regular old boring verb and when to use a cool, unexpected one?

DJK: Back in school, I was told verbs are very important to bringing a scene to life and their power shouldn’t be squandered through use of lazy words like, “are” and “to be,” like I just did in this sentence.

7) One of the things I really like about the stories is that you include a lot of fun “extra” stuff in your work. “Clam Diggers” is very much a story about a man relating how his brother disappeared. Still, you manage to sprinkle in a cool image/story about how the father taught the sons to turn bathroom graffiti swastikas into “neutered” sets of boxes. Unfortunately, writers like me have led sheltered, boring lives, depriving us of the opportunity to come across these kinds of interesting anecdotes and ideas. How many of these cool things in the stories come from your real life? Should sheltered writers like me just allow myself to make up stuff? I’ve obviously never planned an inside job scam on a casino…should I just stop restricting myself and assuming I couldn’t write such a story?

DJK: Neutering swastikas into tiny four-paned windows is a favorite pastime of mine, as I found that moving to Kentucky means more than the usual quota of bathroom-stall neo-Nazi graffiti. See this is where the revolution will begin… on the toilet! And many of the digressions, er, details do come from my day-to-day or past adventures. I did win and lose and win back about three grand at roulette, and I committed all those ridiculous infractions at the roulette wheel at the MGM Grand Casino in Las Vegas. I’d like to say that was research, but it was my friend’s crazy wedding. I didn’t try to scam them, of course. All the flavor that my personal experience can bring to the stories stops just short of the actual crimes. Except for one. Maybe. Sort of. Next question!

8) You REALLY like to start stories with the inciting incident or with a sentence that represents the overarching feeling of the piece or its narrative thrust. See?

Shades: “She was sure one of them was watching her.”

Burning Down DJs: “Before the night ends with me crashing through the woods in a stolen police car, I’ll drive around stuck on one thought.”

Queen Excluder: “There were sitting down to dinner when the phone rang.”

Castrating Firemen: “I will leave work to get you a cigarette because you’re crying.”

Either Way It Ends With A Shovel: (in italics) “Are you going to bury someone? Or dig someone up?”

How much of this is planning and how much comes in the second draft? Are you only doing it because most of these are crime-related stories and plot is really important?

DJK: Those examples were part of the original drafts. I’ve always been a fan of getting things going in the first sentence, to engage both the reader and the writer. And because I can’t wait to get the main idea out, front and center (like the “Are you going to bury someone or dig them up?” question in “Either Way It Ends With A Shovel”) and because I trust myself a little more with the plot rather than the prose. At least until the story gets cooking.

9) So I think I understand why you have thirty stories about authority figures (police officers, firemen, paramedics). It’s probably the same reason I have 150 stories about ugly dudes whose flawed natures has resulted in the fact that none of them have ever had a healthy relationship with a woman. These are topics of particular and personal interest to us, so we’re going to write about them.

What I wanna know is how you figured out the order for all of the stories. (We’re all hoping to have the same assignment someday!) How come the super-long award-winning story was last instead of first? How come the shortest story was first? What kind of experience were you trying to shape for the reader?

DJK: When it turned out I’d accumulated thirty stories that punished police officers, firemen, paramedics, high school coaches, etc., I was kind of surprised. It really wasn’t a conscious effort. Well, there were probably about twenty stories stockpiled with this similar theme before I realized the connection, and then I wrote ten more because I felt like I was on a roll and wanted to get it all out.

It’s still not all out though. A beta reader is going through my novel, The Last Projector, right now, and for kicks he counted up the total uses of the word “cop,” “officer,” and “police.” You might enjoy this with your statistics fetish earlier!

In 500 pages, there are around 700 uses of these terms. Second most used is the word “fuck” with 600. And most of those “fucks” and “cops” are probably pretty closely intertwined. And this is not a novel about police officers. So I guess it’s out of my hands.

As far as the order of the stories, that was sort of complicated:

“Nine Cops Killed…” wraps up the book because it’s the title story, and I feel like it’s a big party, a fun bash where the reader can be rewarded for making it through the whole thing. And the shortest story starts things because “Trophies” felt like a mission statement to me. It had a lot of the elements that are consistent throughout, regardless of the genre hopping.

But as far as the order of the stories, I spend a loooooooong time on that. I definitely “mix-taped” it High Fidelity style. The first “song” starts off fast, then the next song kicks it up a notch. Then the next song slows things down a notch, etc. etc. And I also wanted stories that were first-person to avoid following each other, lest people think those “Jacks” were the same Jack, of course. And I wanted the genres to be spread out, so that people didn’t expect a third monster movie after a monster double feature. And after all that work of mix-taping, I read an article on HTML Giant that declared very definitively that, “Short Story Collections Are Not A Mix Tape!” and then I was satisfied that I had done the right thing.

10) Look at the last few pages of “Clam Digger.” This cool story is told by a first-person narrator who is relating events that happened a long time ago. He therefore has access to a lot more information than the younger version of himself.

So the narrator lets us know this is THE STORY OF HOW HIS BROTHER DISAPPEARED AND YOU CAN BELIEVE HIM OR NOT; HE KNOWS WHAT HE SAW. (We’re also informed he’s participating in some kind of interview.)

So the bulk of the story finds the narrator telling the story in the past tense, chronologically jumping from one significant event to the next.

But check out the end of the story. We’re getting the “money shot,” so to speak. The mystery of the brother’s disappearance is being revealed…

Then you cut to a new section, leaping from the past to the present to the past again. Why did you break the pattern established by the rest of the sections? What was the effect you were trying to create? Are you willing to apologize for my newfound fear of clams and other mollusks?

DJK: I guess that was an attempt to build suspense, sort of use those Sam Peckinpah directorial editing tips where you cut away right when the shot has peaked. I also maybe stutter-stepped there at the end because I wasn’t sure how I was going to wrap it up. The natural ending of that story felt like it should be in the past, since that’s where the mystery was, but there had to be resolution in the present, too. So I tried to do both, at the risk of the dog in Aesop’s fable who growls at his reflection in the water and loses both bones.

“Clam Digger” was also my first run at a “Lovecraftian” story. So I had some tortured soul spinning some yarn about the horribleness he’d witnessed, some large ocean-dwelling critter that may have driven him insane. But other genres started to cross-fertilize while I was writing it, and the story that resulted is really more psychological horror than anything.

I do apologize for your new clam and mollusk aversion, though. But it’s better than an aversion to naming characters, so you should be thankful! And it’s only fair this happened to you because those things freak me out, too. I mean, look at clams for a second, if you have one handy. You think it’s sticking its tongue out at you, but it’s a foot? You think it’s sticking its eyes out at you, but that’s its nose? That’s insanity on the half shell right there.

David James Keaton’s award-winning fiction has appeared in over 50 publications. His first collection, Fish Bites Cop: Stories to Bash Authorities, was named This Is Horror’s Short Story Collection of the Year and was a finalist for Killer Nashville’s Silver Falchion Award. His debut novel, The Last Projector, is due out this Halloween through Broken River Books.

Short Story Collection

2014, Comet Press, David James Keaton, FISH BITES COP!, Why'd You Do That?

Title of Work and its Form: “Never Write From a Place of Despair,” creative nonfiction

Author: Erika Anderson (on Twitter @ErikaOnFire)

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece debuted in Issue 1 of Midnight Breakfast. You can find the work here.

Bonuses: Ms. Anderson is very kind; she offers a collection of her publications at her web site. I particularly enjoy her brief “workshop” of the author photo.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Momentum

Discussion:

This work of creative nonfiction describes Ms. Anderson’s reaction to the aftermath of her divorce. It seems clear that Ms. Anderson was figuring things out at the time and that the piece is an instance in which the author is giving the reader advice that she is also trying to internalize. There are many “rules” in the piece, several “do not”s and “never”s and the final paragraph leaves us with a sense that catharsis is on its way, albeit slowly.

I was first struck by the momentum in the piece. Ms. Anderson grabs you by the lapel and won’t let you go. How does she make this happen? Well, repetition for one thing. A composer uses motifs, short melodic passages, to bring unity and momentum to a piece. Plenty of examples can be found in the best music ever composed:

Ms. Anderson establishes the “never write” motif in her title and employs it in the piece. She eventually brings in “do not,” just as Beethoven cleverly introduces the famous “Ode to Joy” melody to the symphony before he allows it to take over the work and reach full flower.

Ms. Anderson does another thing to build and maintain momentum: she varies the lengths of her paragraphs, just as Beethoven varied the tempi in the movements of the Ninth.

I also admire the manner in which Ms. Anderson confronts one of the big problems inherent in the composition of creative nonfiction: YOU HAVE TO BE HONEST AND SOMETIMES REVEAL SOME OF THE FAILURES OF YOUR LIFE OR THINGS THAT ARE A BIT EMBARRASSING.

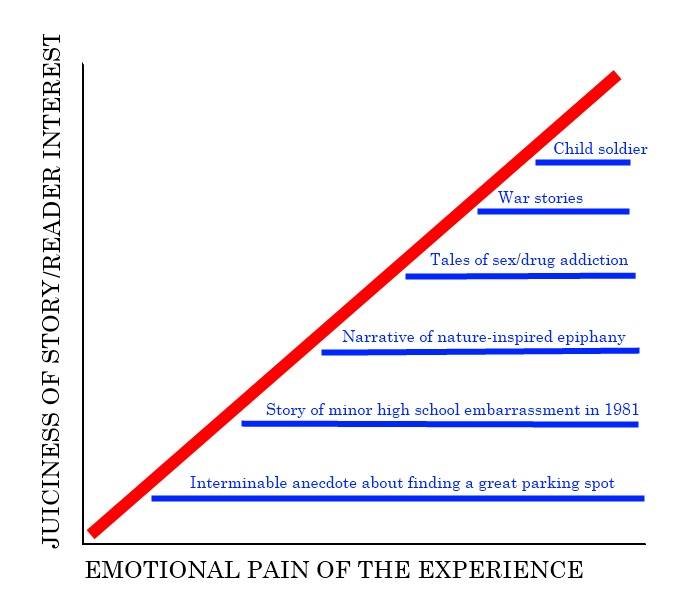

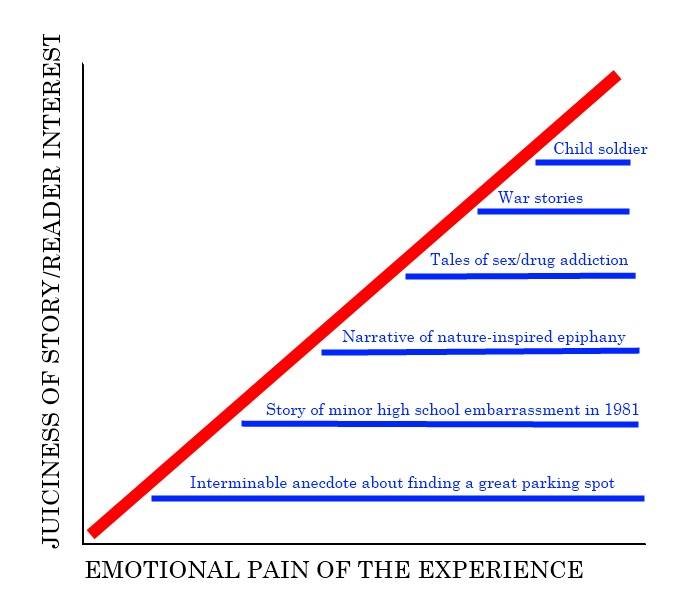

Sad but true: our lives don’t always unfurl according to our plans. We will sometimes fail in our efforts and our relationships. Unfortunately, these are the kinds of truths that we must confess in creative nonfiction. Happy stories are often meaningless or boring. Divorces? They’re usually as painful as they are “juicy.” Think about it this way. Let’s say you’re on a bus and I plop down in the seat beside you and say, “Boy, do I have a story for you. This one time, I stubbed my toe so bad that it swelled up and looked like a grape for a MONTH.” And then I keep talking about it for an hour. You’d go crazy, right?

Now let’s say that Valentino Achak Deng sits beside you and somehow organically mentions that he’s one of the Lost Boys of Sudan. I’m going to bet that you would be interested in hearing his story, even though that story is ridiculously sad and should never, ever happen in reality.

I think my ultimate point is that we NEED to confess and to bare ourselves in order to create powerful works of creative nonfiction. There may certainly be exceptions, but we spend our lives surrounded by people who hide behind projections of how they want to be seen by others. Writers such as Mary Karr are brave enough to expose their flaws. Not only are her stories more interesting than most, but they’re also more powerful.

Here are my thoughts in chart form:

Ms. Anderson’s story definitely doesn’t fall on the bottom of the red line. You don’t have to be Harold Bloom to pick up on the fact that Ms. Anderson is telling us that she was in that “place of despair.” She reveals that she may not have known her ex-husband as well as she thought. She’s brave enough to confess that she was adrift in her thirties…not the best situation, for sure.

Ms. Anderson’s story definitely doesn’t fall on the bottom of the red line. You don’t have to be Harold Bloom to pick up on the fact that Ms. Anderson is telling us that she was in that “place of despair.” She reveals that she may not have known her ex-husband as well as she thought. She’s brave enough to confess that she was adrift in her thirties…not the best situation, for sure.

It seemed to me that Ms. Anderson was being very honest with the reader, but was also employing a technique that allowed her to be frank with us. She gains distance from us through her use of point of view and choices of words. For example, here’s a passage from the piece:

You thought your husband never loved you because he could never touch you the right way. He hated that there was a right way — he wanted to pet you like a puppy, to paw at your blonde-haired forearm, to stroke the heft of your thigh, for that to be good enough. But it wasn’t, and that broke him and it broke you.

We have been told the story is nonfiction, so we assume it to be true. Ms. Anderson, however, employs the second person point of view. Why not use first person? She’s writing her own story, after all! Well, the second person allows the writer to push the reader away a little bit. We can “trick” ourselves into believing that we’re not really confessing our own problems…we’re writing about the reader’s life, right? See? It says, “You!” That means the reader! Compare the above passage after a transformation into first person:

I thought my husband never loved me because he could never touch me the right way. He hated that there was a right way — he wanted to pet me like a puppy, to paw at my blonde-haired forearm, to stroke the heft of my thigh, for that to be good enough. But it wasn’t, and that broke him and it broke me.

The sentences read differently, don’t they? The second person offers a layer of psychological protection and it also subtly turns the reader away from thinking that you might simply be complaining or laying down a list of grievances. (Not that I think Ms. Anderson is doing those things, of course.) Instead, Ms. Anderson subconsciously forces the reader to immerse him or herself in her experience. There’s no PROPER point of view for creative nonfiction (or any piece), but the point is to create the conditions under which you can tell the most faithful version of your story. If you need to switch POV, so be it.

What Should We Steal?

- Employ motifs and changes of pace to maintain narrative momentum. A speaker uses the inflection of his or her voice to keep people interested. The same principles apply to writing…just in different ways.

- Accept the fact that writing great creative nonfiction may require you to tell people your dark secrets. Everyone has a walked-out-of-the-bathroom-with-toilet-paper-stuck-on-shoe-on-a-first-date story. You may have to plumb a little deeper if you want to tell a story that will capture your reader.

- Make any changes you need to ensure you put down an honest and powerful version of your true story. I wrote a brief CNF story about something sad that happened to me when I was a kid. I simply told the true story in the form of a pulp detective short story. On the off chance it ever gets published, perhaps I’ll explain my reasoning.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Beethoven, Erika Anderson, Midnight Breakfast, Narrative Momentum