Title of Work and its Form: “Charity,” short story

Author: Charles Baxter

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in Issue 43 of McSweeney’s. Heidi Pitlor and Jennifer Egan chose to include the work in Best American Short Stories 2014.

Bonuses: Karen Carlson always has some interesting thoughts to share, this time about Mr. Baxter’s story. Here is a Midwestern Gothic interview in which Mr. Baxter discusses his connection to the region. Want to see what Mr. Baxter said about his work at St. Francis College?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

When Matty and Harry met, they were Americans living in Africa, doing what they could to help sick people. Harry loved that Matty/Quinn was filled with kindness for the people around him and wasn’t helping out in hopes of making a profit. As the Bard might say, the course of true love never did run smooth. Though they remain boyfriend and boyfriend after returning to the States, Matty ends up living in a friend’s basement, addicted to the painkillers that are his only relief from the pain caused by a sickness even the Mayo Clinic can’t identify. The story is split into two sections; the first describes the dire straits in which Matty finds himself and the second is a first-person account of Harry’s trip to Minneapolis to find and help his boyfriend.

Mr. Baxter tricked me! Ever since grad school, I’ve been in the habit of jotting down the story’s point of view and the names of the important characters. Doing so helps me remember the story the next time it’s brought up and addresses one of my blind spots: I’m REALLY bad at remembering character names. So I started reading “Charity:”

I

He had fallen into bad trouble. He had worked in Ethiopia for a year…

So I uncapped my fountain pen and wrote: 3RD and eventually QUINN. All was well and good until I reached the next section:

II

That was as far as I got whenever I tried to compose an account of what happened to Matty Quinn-my boyfriend, my soulmate, my future life…

Uh oh. That’s first person. What’s going on? Well, Mr. Baxter has made a fantastic choice: that’s what’s going on. Even though Harry most certainly asked Matty about what happened in Minneapolis, he was not there for every moment. The story therefore benefits from casting the first section in third person. The narrator (Harry, in this case) is able to immerse the reader in the story much more deeply than if he had to tell the tale from a distance. Further, the first section really does belong to Matty; he’s the protagonist in the events, he’s the focal character…so the story SHOULD be told from his perspective. The second section, on the other hand, is very much Harry’s story. He’s the one who meets up with Black Bird and who does what he can to bring Matty back to life.

If you’re lucky enough to have the Best American volume, you can read the end notes that accompany each story. Mr. Baxter reveals the most fascinating piece of information regarding the genesis of “Charity:”

…I had just written a story called “Chastity,” in which my protagonist, Benny Takemitsu, gets mugged, and I thought, “I wonder who did that?” Whoever did it had to be desperate. Whoever it was, I thought, might be a good soul in the grip of something truly terrible. So I wrote it that way.

Isn’t that cool? Mr. Baxter’s choice offers a couple powerful advantages:

It’s really hard to come up with story ideas, isn’t it? Cherry-picking an event from another of your works can be the inspiration that gets you going on a new story. If you look at any of your stories, you’ll surely see all kinds of avenues ripe for exploration. Hmm…here’s what I’m thinking I could poach from my story, “Something Like a Sin:”

- Who are some of the other people who attend Transformation Baptist? What are they like?

- What else could happen in The Raven, the bar the protagonist frequents?

- What is Pastor Hocking’s family like? When has he failed to live up to his own standards?

- What happened with all of the other women the protagonist mentions?

- Who is in the house when Melody closes the door behind her?

See? If I’m dry for inspiration, looking to my past work can give me a jumpstart.

Mr. Baxter also gains something very important by reusing Benny Takemitsu’s mugging: he’s creating a discernible world. Isn’t it comforting to know that all of the Marvel characters know each other and can sometimes team up, for good or evil? Tying these two stories together makes Mr. Baxter’s Minneapolis seem more like a real place. Creating the mythology is also a good idea in light of the fact that Mr. Baxter is publishing a collection of stories about “virtues and vices:” Chastity, Charity, Refraining From Watching the Next Breaking Bad Episode on Netflix Before Your Spouse Does, and so on. A shared world only strengthens the conceit of the book.

What Should We Steal?

- Tell your story from the most appropriate and interesting point of view. Sure, you may have to break your story into sections and change POV, but that’s okay if it’s done in the service of the story.

- Borrow characters and situations from your other works. Even if it’s just a cameo from another character’s friend, people who read your work will find greater depth in the world you create.

Short Story

2013, Best American Short Stories 2014, Charles Baxter, McSweeney's, Point of View

Title of Work and its Form: “My Last Attempt to Explain to You What Happened with the Lion Tamer,” short story

Author: Brendan Mathews

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story made its debut in the Summer 2009 issue of The Cincinnati Review. The piece was subsequently selected for Best American Short Stories 2010 by Heidi Pitlor and Richard Russo.

Bonus: Here is a writing lesson Mr. Mathews published on the Ploughshares blog. Here is an interview Mr. Mathews gave to Port. Here is what Ann Graham thought of the story.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

Mr. Mathews employs an interesting point of view in this story. The tale is told by a first-person narrator to an interlocutor: a trapeze artist. He addresses her as “you,” and tries to give his side of the story, explaining why things didn’t end up so well for the man who acts as the lion tamer for the circus that also employs both of you. The narrator, a clown, is in love (or at least is infatuated) with the trapeze artist. He begins his explanation at the beginning. He was attracted to her because of her skill under the big top and, yes, her beautiful face and body. Alas, the lion tamer won her affections and the clown responds by turning his routine into a dumb show intended to mock the lion tamer. As is the case with all love stories, there are unanticipated twists and turns, and no one ends up happy. (Sorry…I’m a pessimist at heart.)

First, I’m going to point out that Mr. Mathews borrowed from Hamlet, whether he knew it or not. The narrator’s jealousy leads him to strike back in a manner unique to his situation. He plans to perform a parody of the lion tamer’s underwhelming act using Scottie terriers instead of giant cats. The narrator expects the audience to release great peals of laughter as they mock his romantic rival. Now, it doesn’t work out that way in the story, but Mr. Mathews gets a great deal of mileage out of describing the image. We’ve all resented those who stand in the way of the man or woman we love (or think we love), and wouldn’t it be great to enlist a couple thousand people in your campaign to make the rival feel terrible about themselves?

How did Mr. Mathews borrow from Hamlet? Well, Hamlet makes the same kind of plan. The traveling players follow the prince’s script, acting out the way in which Claudius killed Hamlet, Sr. This dumb show is the confirmation Hamlet needs; when Claudius reacts, Hamlet knows his father’s ghost was right and that he must get going with the whole revenge thing…in two more acts. So what should we steal from Mr. Mathews? (In addition to borrowing from the Bard?) I love that the author creates such a powerful image in the reader’s mind and then subverts it. The powerful visual in the short story drives the plot, just as the dumb show propels the narrative in Hamlet.

The point of view that Mr. Mathews chose makes a big difference in the story. I love that the clown is telling the story to the trapeze artist. Why? Because he loves her. People are (usually) more likely to be honest with someone they love. Further, these are some very raw emotions. He knows that she doesn’t love him back, but still has some hope that she will begin to see something special in him. He doesn’t want her to hate him because of what happened.

The point of view is possibly most powerful just before the climax of the story. If you’re a longtime reader of GWS, you may already know where I’m going with this. There’s a gut-punch moment when the clown makes the mistake of telling the object of his affection how he feels:

“Say something funny,” you said, your eyes like jewels in the lamplight.

“I love you” tumbled out of me, the words pushing their way into the open like clowns from a car.

“That’s not funny,” you said, and your eyes snapped shut like I had slapped you.

And you were right. It wasn’t funny-it was hilarious. Coming from me, it was absolutely ridiculous.

As time crawled from one second to the next, your head ticked from side to side and a slow-motion no, and I could feel the pressure of all the things I’d left unsaid mounting in my head. If I had been a cartoon, steam would have shot from my ears.

The clown is going to describe this moment differently depending on who is listening to him. How would things be different if he were talking to a group of men? Well, he might tell the story in such a manner that he comes off as less emotionally vulnerable. What if he’s telling his possible future children how he felt about the trapeze artist? He might take on a more didactic tone. Alas, the clown is talking to a woman he loves who will never love him back, a woman he unintentionally hurt. Is there any better way to attack this particular story?

What Should We Steal?

- Allow your powerful visuals to drive the narrative. Making your reader chuckle or sigh with a powerful visual concept is great. A far harder and more powerful trick is to make that concept drive the plot, as well.

- Enhance your first person narrator’s honesty (or dishonesty) by unspooling the story to the appropriate interlocutor. I don’t think I’m alone in saying that I’m going to be much more honest when telling the story to a friend than the waitress who asked why I was getting breakfast at three in the morning on Christmas Eve while wearing the Elton John Donald Duck suit.

Short Story

2009, Best American 2010, Brendan Mathews, My Last Attempt to Explain to You What Happened with the Lion Tamer, Point of View, The Cincinnati Review

Title of Work and its Form: “Going Down on Polypropylene,” creative nonfiction

Author: Alicia Catt

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece can be found in Volume 2, Issue 9 of Pithead Chapel, a fine online journal. Go check it out.

Bonuses: Here is another work of creative nonfiction that Ms. Catt placed in The Citron Review. Here is a piece from decomP Magazine about trichotillomania. And another piece from Mary: A Journal of New Writing.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

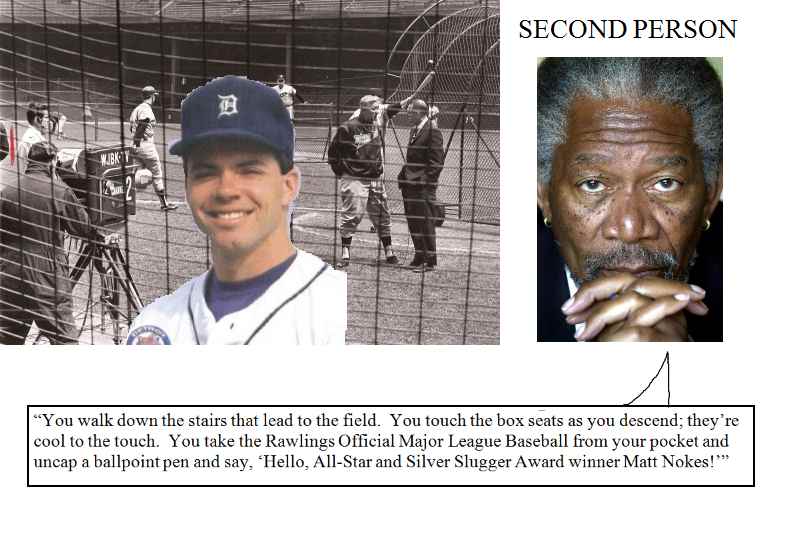

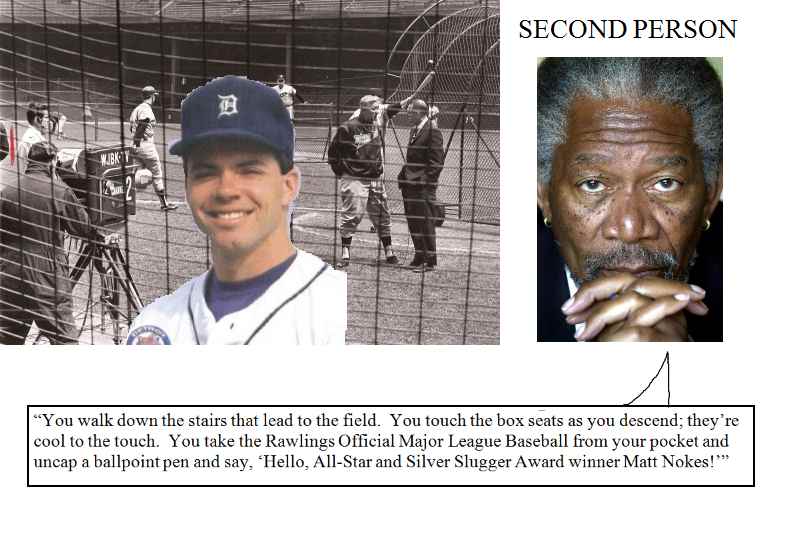

At the age of twelve, Ms. Catt was devoted to the environment and lived in perpetual fear of what the other people would say about her. Were any of us at our best at twelve? Ms. Catt was a little overweight and was uninformed and confused about sex. Based upon that last description, I might have thought this piece was about me. But there’s another reason: the piece is in second person. You meet a woman who doesn’t quite belong in small-town Wisconsin who knows a lot about sex. You blush when she simulates a sexual act with a pudding cup. You are sad that Carrie gets abused, but you are glad that her presence pushed you onto a higher rung of the social ladder. Carrie is gone before long and you suffer one more indignity; the soda cans you picked up during a field trip contained ants that crawl around on you during the bus ride back to school. Ah, adolescence.

So the first thing that I noticed about the story was the point of view. The piece has been classified as nonfiction, so I was a bit surprised to see that Ms. Catt employed the second person. After all, this is ostensibly HER story and the events described (pretty much) really happened. (Depending, of course, how much Ms. Catt agrees with Pam Houston’s thoughts regarding truth in nonfiction.) What does Ms. Catt gain by taking HER story and putting it onto YOU?

- Novelty. There are second-person memoirs out there, but you don’t see these kinds of works every day. Readers can be compelled by aberrations from the norm, so Ms. Catt earns attention from her first sentence. (It becomes her responsibility, of course, to keep that attention and does so with some beautiful sentences and turns of phrase.)

- The reader is aligned with the author. As I’ve pointed out, the second person reduces distance between the narrator and writer; Morgan Freeman is not only talking to you, but he’s telling your story! Here’s the graphic I made using my hype MS Paint skyllz:

- The reader has an easier time remembering his or her own adolescence. It’s been a long time since I was a teenager and I’ve blocked out a lot of the feelings and events I don’t want to remember. Ms. Catt cuts through that defense mechanism with sentences such as, “But you’re made of oddity.” Once Ms. Catt puts you in a mental state in which you can remember how you felt as a teenager, her own awkwardness and longing become more potent.

One of the facets of prose that has been a challenge in my own writing is figuring out how best to cast my scenes. When I was younger, I was often tempted to have my third person narrators go overboard with their DIALOGUE AND DESCRIPTION OF SMALL EVENTS. In that way, I was failing to make use of the fiction writer’s toolbox. In a play or screenplay, a writer has no narrator (you know what I mean) and can really only make use of dialogue and action. Fiction writers can make use of a narrator who simply tells the reader what they need to know and fast-forwards when they need to.

There are no SCENES in “Going Down on Polypropylene,” though there is plenty of scene work. Consider this scene from Ms. Catt’s piece:

You beg your mother for rides to Econofoods, and burrow through the grocer’s dumpster to recycle every scrap of corrugated cardboard they’ve mistaken for waste. Even when you cut your fingers on sticky, dark things, you keep digging and sorting. You dig and you sort until your mother’s had enough and drags you home.

See how boring that scene would be if it were written as a real scene?

Alicia stood before the grocer’s dumpster, plastic bags on her hands in a futile attempt to prevent her from touching the slimy garbage. She loved the environment, but the aroma of hot, wet garbage made her sick.

Alicia’s mother was inside and would be done shopping soon. Alicia had to be quick. She opened up the clear recycling bag and started grabbing for cardboard. Sharp edges nipped at her fingers…

See? Boring. And not just because I wrote it. Ms. Catt makes the felicitous choice to tell us enough to imagine the scene without getting bogged down in the boring and unnecessary.

What Should We Steal?

- Select an unexpected point of view. Why not a second person memoir? Why not tell the story of a historical event from a first person point of view?

- Allow your narrator to describe scenes instead of writing them as scenes. In prose, the narrator can zip through time, reach into the minds of others and work all kinds of other magic. Take advantage of these superpowers!

Poem

2013, Alicia Catt, Pithead Chapel, Point of View, Second Person, trichotillomania

Title of Work and its Form: “A Bridge Under Water,” short story

Author: Tom Bissell

Date of Work: 2010

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in Issue 71 of Agni, an excellent lit journal. Feel free to order a back issue from those fine folks. You may also access the story through EBSCO; feel free to ask your local librarian how to do so. They love helping people with this kind of stuff.

Bonuses: Here is a New Yorker article about Mr. Bissell’s involvement with video game writing. Here is Karen Carlson’s interesting analysis. (There is indeed a big difference between “liking” a piece and “admiring” it. Here are Ann Graham’s thoughts. Here is the Carol’s Notebook review of the story.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

“He” and “She” are celebrating their recent marriage in Rome. A hearty congratulations to them. He is slightly older than his wife of three days, but may be a little more immature than she. The narrator makes it VERY clear that there is conflict in this union, not the least of which is their religious difference. She wants the child in her belly to be raised Jewish (even though she’s not very faithful) and he is not at all religious. He and she make the Roman rounds, ending up in the city’s biggest synagogue. He isn’t very pleased that the synagogue segregates men and women during services, so he causes a mild scene in protest. She just wants to go with the flow, but he doesn’t allow it; they are escorted out. Hand in hand, this “one story” ends and the characters proceed into the rest of their lives.

This story is particularly notable for its third person narrator. It seemed to me that he or she or it is clearly on the side of the woman. What makes me think so?

- In the first paragraph, He is described as a bit of a glutton, “vacuuming up” a plate of pasta, gulping a glass of wine in three swallows and “single-handedly” consuming half a basket of breadsticks. (That last one doesn’t seem so bad. If two people are eating, isn’t it polite for one person to limit himself to half of the table’s supply of breadsticks?)

- In the second paragraph, She is described as eating in a very civilized manner and He “put away everything from foie gras to a Wendy’s single with the joyless efficiency of a twelve-year-old.”

- In the fourth paragraph, He accidentally clears crumbs from his lips and has shaggy “tinder-dry” brown hair.

So He is immature and has difficulty avoiding gluttony (my favorite of the Seven Deadly Sins). Why does it matter that the narrator seems to be against Him? It’s not a problem, really. I think that the narrator is “sticking up” for Her. There’s a bit of an imbalance of power between the two. He is thirty-four and she twenty-six: two very different ages. She is pregnant and must deal with the impending change in a physical manner that simply escapes Him because of human biology. He’s a lot more outspoken with his disdain for religion; she seems to be working through her own conflicts in a much quieter manner.

When you write in the third person, you must decide how close this voice will be to the characters. Will the narrator have access to everyone’s thoughts or only those of one character? Will the narrator be impartial or take an extremely active role in shaping the reader’s understanding of events? It seemed to me that Bissell (whether consciously or subconsciously) put the narrator in Her corner.

Whether or not you realize it, the white space at the end of your story has meaning. That, after all, is the place where your characters will continue to live their lives. Mr. Bissell has given us a newly wed couple suffering from friction and possible incompatibility as well as a gestating baby. The final sentence of the story is not the end for He and She. So what happens in the future?

Mr. Bissell lays in some clues. Early on, we’re told that She plays Rock, Paper, Scissors a little differently than the rest of us. You can throw Fire, capable of destroying the other three, but you can only throw it once in a lifetime. A page later, He uses his Fire and reminds her, “you’ve still got yours.” Indeed. This is a little bit like Chekhov’s Gun. Her Fire. She’s going to throw it at SOME point in the white space at the end of the story.

With a page to go in the story, Mr. Bissell’s narrator says the following as He and She are being escorted from the synagogue:

At this her husband turned to her in something close to lip-licking panic. Not that he was being forcefully removed from a place of worship-she knew he would tell this story, with certain redactions, for years-but rather at the thought of everything else that had been set in motion here.

So Mr. Bissell isn’t writing a novel here. We don’t know EXACTLY what will happen. But we do know that He will tell this story for a long time and that something has been “set in motion.” What’s the effect of these hints? There’s a lot more weight to the events of “A Bridge Under Water” and the reader brings a lot more to the last sentence of the story.

What Should We Steal?

- Empower your narrator to be a character in the story. When you’re gathered around a campfire, the storyteller can’t help but become part of the tale. Why shouldn’t it be the same for the narrator of a short story?

- Sprinkle in hints as to what will happen after the story is over. There may be no more typing after the final sentence, but your characters are still walking around and living their lives.

Poem

2010, Agni, Best American 2010, Point of View, Tom Bissell

Title of Work and its Form: “Tenth of December,” short story

Author: George Saunders

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story premiered in the October 31, 2011 issue of The New Yorker. You can read the story here. You can also find the story in the 2012 anthology of Best American Short Stories. The story headlines Mr. Saunders’s book Tenth of December. Why not pick it up from an independent bookseller such as Reno, Nevada’s Grassroots Books? (They seem very cool!)

Bonuses: Here is an interview in which Mr. Saunders discusses “Tenth of December.” Here is what blogger Karen Carlson thought about the story. (She makes interesting points about the POV and describes her understandable “struggle” with the story.) Here is Mr. Saunders’s page at This American Life. (You know you love This American Life.) Yes, Mr. Saunders is a very influential man.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

Robin is a slightly chubby schoolboy. Don is a middle-aged father who is suffering from cancer and is determined to commit suicide. How are these two unrelated characters related? One of those good, old-fashioned twists of fate. Don leaves his coat on a chair to help the authorities locate his body. Unfortunately, Robin decides to try and do a good deed and bring it to him. Robin takes a shortcut across a frozen pond. What happens when Robin falls into the freezing water?

Mr. Saunders’s story is a very interesting study. The narrator is a very close third person alternating between Robin and Don. The narrator absorbs each character’s idiosyncracies; Robin is pretending he is talking to a girl he likes and that he is surrounded by supernatural woodland creatures and Don’s brain is failing because of illness. I noticed that the story “threw” Ms. Carlson at first; the same thing happened to me, but in a different way. For a few pages, I was under the impression that the “Nethers” were real. (You know, short story real.) Mr. Saunders describes the world of the Nethers and what they look like and how they act and so on, going into a great deal of depth. Very quickly, however, I was right on track. Mr. Saunders had to do what he did in order to immerse the reader in Robin’s brain and to establish the close POV that works so well in the story. What lesson can we take away from this? A reminder that the first couple pages of your piece establish the unique world in which your characters live. Readers are willing to follow you ANYWHERE, so long as you make the ride smooth.

Think about Kafka’s Metamorphosis. Remember the first sentence?

One morning, as Gregor Samsa was waking up from anxious dreams, he discovered that in his bed he had been changed into a monstrous verminous bug.

Kafka (like Saunders) doesn’t mess around when establishing his conceit. Guess what, Kafka seems to say. This is a world in which Gregor Samsa turned into a giant bug. Deal with it. Saunders has the same strong kind of declaration: Hey, reader. You’re in the head of a young boy who likes a girl named Suzanne and has a great imagination.

The choice to craft the story from the separated points of view of two different characters gives Mr. Saunders at least two big bonuses:

- Mr. Saunders can offer, very gracefully, two different accounts of the same event. And why not? Each POV character is experiencing them on their own terms.

- Mr. Saunders can allow the characters the same kind of first-person confessional without allowing the other character to get in the way. We don’t need Don’s commentary on Robin’s crush on Suzanne and Robin shouldn’t be allowed to give us his commentary as Don does what he can to keep the kid warm.

As we can all attest, coming up with titles is a pain. How did Mr. Saunders do it? “Tenth of December” is great because even if it’s not the date on which the story takes place, it evokes a time in which the weather (in the Northeast) is cold, but not cold enough for there to be ten feet of ice on the local lake. I also get a Tropic of Cancer vibe from the title. (Ooh, and that’s one of Don’s problems. Cool.) So here’s another title formula:

TITLE FORMULA #8675309: The date on which the story takes place, or a date on which the story COULD take place.

What Should We Steal?

- Think of your first few pages as orientation for your reader. Before you get in a ride in an amusement park, you spend 45 minutes in the queue, learning about the “world” of the attraction. (Your stories are attractions too, right?)

- Employ parallel and severely limited third-person points of view. You gain contrast and a kind of intimacy.

- TITLE FORMULA #8675309: The date on which the story takes place, or a date on which the story COULD take place.

Short Story

2011, Best American 2012, George Saunders, Point of View, The New Yorker

Title of Work and its Form: “Alive,” short story

Author: Sharon Solwitz

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story appears in the Spring 2011 issue of the Fifth Wednesday Journal. Heidi Pitlor and Tom Perrotta subsequently chose to include the story in Best American Short Stories 2012.

Bonuses: Here is a 1997 Chicago Reader article about Ms. Solwitz. Writer Karen Carlson offers some sad and appropriate thoughts about the story. Much happier news: here‘s a Sharon Solwitz story that was published by the Superstition Review.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

This is not a good time for Dylan. His older brother Nate is being treated for cancer and his mother is naturally preoccupied with Nate’s condition. In Dylan’s mind, Nate gets all the attention…everything is determined by what Nate is up for…Nate, Nate, Nate. Dylan finally gets to have some fun: Mom takes the boys on a ski trip. There’s even a cute girl in the ski rental hut! Dylan’s fun seems over when Nate suddenly doesn’t feel well and countless people, including his mother, are tending to the eyebrowless young man who clearly is having some health problems. What does an adolescent boy do in such a situation? He takes off and ends up skiing alongside the cute girl. Dylan, of course, ends up taking a terrible spill. A group of bystanders surround him and his poor, stressed-out mother gives him some attention. I can’t advocate Dylan’s methods—the woman doesn’t need more stress—but his plan worked.

One of my tendencies when writing fiction (we should all know our tendencies) is to want to put dialogue into every scene. The problem with this inclination is that it leads me to neglect all of the other ways in which exposition and dialogue are communicated. The situation in Ms. Solwitz’s story requires a lot of silent scenes. Dylan is a teenage boy who often feels alone and is alone. One of the boy’s problems is that he feels neglected. He’s going skiing alone…there simply must be lots of non-dialogue scenes. Ms. Solwitz makes a wise choice in the story’s point of view. The third-person narrator is very close to Dylan, who isn’t very good at expressing himself or even understanding his own emotions. Because Ms. Solwitz has deep access to Dylan, she can point out the traditional teenage way of thinking: even the ski poles have it in for him! It’s “Dylan against Things.”

One of the many things I love about the story is the way the narrator offers the reader an understanding of the complicated family dynamic. Nate, the sick brother, has a lot on his plate. Ms. Solwitz does not put Nate on a pedestal simply because he is ill. Instead, she does something much kinder: she makes the boy seem human. The kid has flaws and strengths and is not simply a cardboard cutout of a character. For instance, Nate tries to ease his mother’s fears about skiing because he knows what it means to Dylan. Nate complains about math and may or may not have lost a race with Dylan on purpose.

Some folks have a tendency to make saints out of humans in their fiction. Personally, I’d rather be a human than a saint. (Saints, after all, are dead.) Super-sympathetic characters are often depicted as flawless and all-knowing and magical. Think of the wheelchair-bound guest star on a TV drama…they’re there to offer the moral of the story. Those flat stock characters are also boring. Think instead of Dave Dravecky. Mr. Dravecky was a very good major league ballplayer. In 1988, doctors discovered a tumor in one of the muscles in his pitching arm. Doctors treated him and removed half of his deltoid muscle. The gentleman made his way back to the major leagues and won his first start. Then…in his next start…in what is one of the most painful-to-watch baseball highlights of all time…Mr. Dravecky broke his arm while pitching. Sadly, the cancer had returned and Mr. Dravecky, a man who was a MAJOR LEAGUE PITCHER suddenly lost his pitching arm. Mr. Dravecky seems like a very good man and seems to be very happy. If you met him, do you think he wants you to assume he’s a perfect and flawless and mythological creature? Nope. I’m betting he’d admit that he’s just a human being. Just like your characters, there are times when Mr. Dravecky is short-tempered, there are times when he’s angry for no good reason and there are comments he wishes he could take back.

What Should We Steal?

- Silence your characters when appropriate and choose a felicitous POV. Writing a confused teenager may be hard if you describe him or her in a very limited third person point of view.

- Imbue your sympathetic characters with less than sympathetic traits. A child with leukemia should be depicted in an honest manner, even if it’s not always flattering. A single father with several small children is a real human being with real desires. We may not want to think about it, but he needs the company of a woman on occasion!

Short Story

Best American 2012, Fifth Wednesday Journal, Point of View, Sharon Solwitz

Title of Work and its Form: “Honeydew,” short story

Author: Edith Pearlman

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was published in the September/October 2011 issue of Orion Magazine.

Bonuses: Here‘s a nice profile of Ms. Pearlman from Hadassah Magazine. Ooh, and here‘s an interview Ms. Pearlman did with The Millions. (She offers some wonderful thoughts about the importance of short fiction.)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

Even though Caldicott Academy is a prestigious day school for girls, there’s a lot of complicated adult passion lurking beneath the surface. Alice Toomey is the headmistress; she’s having an affair with Dr. Knapp, the professor of anatomy. Dr. Knapp’s daughter, Emily, has an eating disorder and is infatuated with insects. The Caldicott campus is also home to a ravine that is forbidden to students because of “the suicide [that] had occurred a century earlier.” Ms. Pearlman’s story meditates on the characters’ infatuations (sex and the female body and insects) before the threads of the story are united in the climactic scene. Dr. Knapp is sneaking back home after a special moment with Alice. Emily has climbed down the ravine and is watching her father behave “like a boy.” A brief epilogue sums up what happens to the characters and restates what may be the story’s primary theme: “Caldicott’s most important rules, even if they weren’t written down, were tolerance and discretion.”

Ms. Pearlman’s story makes particularly interesting use of the third person omniscient point of view. The narrator has access to the consciousnesses of each of the characters; there are positives and negatives inherent in the choice. Ms. Pearlman, of course, uses the third person omniscient to get all of the story’s issues and conflicts into play very quickly. Because the narrator has full access to everyone, it can simply plant all the seeds it desires. Once the field has been seeded, of course, the writer is able to nurture the plants that have taken root.

The point of view that Ms. Pearlman chose allowed her to make the most impressive move in the story. The penultimate section of the story details Dr. Knapp’s “walk of shame.” The three primary characters are involved, either as spectators or as participants. The third person omniscient acts like a hovering camera. First, Emily sees her father and thinks about what the man’s actions mean. She compares him, of course, to an insect. Then the narrator magically slides to Alice’s point of view; we understand why she begins crawling toward Emily and how her attitude toward the girl has changed. Finally, the camera slides to Richard’s perspective. Two of the women in his life are in danger and resemble insects in different ways. The climax of “Honeydew” means more because Ms. Pearlman offers us a great deal of access to the characters during the climax and does so at a crucial time.

What Should We Steal?

- Plant the seeds of your conflict early and close together. The third-person omniscient makes it easy for you to get your drama started and to establish your primary thematic imagery.

- Imagine the narrator is a kind of camera that must follow rules dictated by the point of view. The third person omniscient narrator can go anywhere and do anything…take advantage of this quality.

Short Story

2011, Best American 2012, Edith Pearlman, Orion Magazine, Point of View

Title of Work and its Form: “Alma,” short story

Author: Junot Diaz

Date of Work: 2007

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story was originally published in The New Yorker. As of this writing, the story is available on the magazine’s web site. “Alma” is part of Mr. Diaz’s short story collection, This Is How You Lose Her. Hey, the Internet isn’t all bad; here’s a video of Mr. Diaz reading his story.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

Junot Diaz is one of this generation’s vast pride of literary lions. The Dominican-American broke through big time with The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao and is now collecting awards when he’s not teaching at MIT. “Alma” features many of Mr. Diaz’s common themes and literary techniques. The second-person story stars Yunior, a young man challenged by fidelity. The story employs a hyperkinetic, hyper-heterosexual diction that reads like a conversation with a lively and worldly friend. Yunior is proud of his Dominican heritage and sees the world through a lens influenced by the language and culture.

The story establishes point of view very quickly and introduces the titular character and how Yunior feels about her:

You, Yunior, have a girlfriend named Alma, who has a long tender horse neck and a big Dominican ass that seems to exist in a fourth dimension beyond jeans.

That’s right, we’re in second-person. YOU are Yunior and you spend a lot of time thinking about Alma’s behind and dreaming up alternate ways of describing it. For three pages, YOU experience the life that Yunior and Alma share. She’s a good woman, learning Spanish for YOU with opposite interests and a free attitude in bed.

Then you find out that YOU are “also fucking this beautiful freshman girl named Laxmi.” YOU discover that Alma is not very happy about that and YOU try one great lie, but “this is how you lose her.” (I love when a book’s title appears in the story!)

Diaz makes the story immediate and personal and summarizes the relationship at such a breakneck pace that the reader has no choice but to follow along. The second-person point of view explicitly puts the reader in the position of your protagonist, so the narrative distance is already substantially decreased. Diaz keeps you even more involved in the story with his long, intense sentences. For example:

Alma is slender as a reed, you a steroid-addicted block; Alma loves driving, you books; Alma owns a Saturn, you have no points on your license; Alma’s nails are too dirty for cooking, your spaghetti con pollo is the best in the land.

The story is only a few pages long; these kinds of sentences accomplish multiple aims. They add characterization while releasing exposition and establishing tone all at once while adding momentum to the story. Mr. Diaz knows he doesn’t have a lot of page space, so he makes the most of every line.

What Should We Steal?

- Lock the reader in with second person and pull them along for a ride. We spend so much time in first person; it can be refreshing to relax into a different consciousness.

- Employ longer sentences to decrease narrative distance and increase intensity, particularly in a very short story. There are times when short and simple is fitting. (For example, saying “I love you.”) On the other hand, long, energetic sentences can also do a lot for you when employed properly.

Short Story

2007, Junot Diaz, Point of View

Title of Work and its Form: “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” short story

Author: Flannery O’Connor

Date of Work: 1953

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story first appeared in an anthology of new works in 1953, but can easily be found in countless collections. Why not pick up Flannery O’Connor’s Complete Stories?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Point of View

Discussion:

“The grandmother didn’t want to go to Florida. She wanted to go visit some of her connections in east Tennessee and she was seizing at every chance to change Bailey’s mind.” If only Bailey had listened to Grandma. The family goes on their trip, with Grandma’s running commentary serving as a backdrop. During a stop at The Tower for some “barbecued sandwiches,” the Grandmother starts a brief discussion about The Misfit, an escaped convict whose specter has been scaring people. The family gets back on the road and later have an accident. Who should stop by but The Misfit? In short order, the young people are killed by The Misfit’s gang and the grandmother is begging for her life. When she actually touches The Misfit, he shoots her dead. The gang briefly discusses the incident as the story comes to a close.

When I first read the story, I wasn’t struck most by the violence. I wondered how the heck Flannery O’Connor was going to end the story. The grandmother is such a fun character and Ms. O’Connor allowed us to live with her for sixteen pages. The story is in the third-person and most of the internal details are about her or from her perspective. What do you do after your focal character, your font of insight, is dead?

What did Flannery O’Connor do? First of all, she kept things short and sweet. There’s about half a page of text after the grandmother is shot. (The climax.) O’Connor restricts herself to only dialogue and factual reporting; there’s no more insight into characters’ thoughts. (“Then he put his gun down…” “Hiram and Bobby Lee returned from the ditch…” “The Misfit’s eyes were red-rimmed and pale…”)

What could these choices mean?

- From what I understand, many victims of gunshot wounds don’t die immediately. Depending on where in the chest she was hit, the grandmother could have lived until there was no longer any blood in her brain. (Or whatever…feel free to ask a doctor.) The point is that the very brief post-grandmother period of the story could represent the last things that she hears before she finally breathes her last.

- O’Connor could be suggesting that the time for philosophy in the story is over and her intent is to allow the reader to focus on the actual action and dialogue in the piece. Without her guidance, O’Connor empowers you to figure things out for yourself. The Misfit’s last two lines are extremely meaningful with respect to the story’s theme.

- O’Connor could have wanted to reinforce the way the narrator has changed. In the beginning of the story, the narrator seems very conversational. By the end, the narrator is merely a reporter.

The religious imagery and parallels in the story are inescapable. In a strange way, “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” reads like a parable or is reminiscent of a sermon or homily. The narrator strips everything else away, allowing the lesson to shine through on its own.

What Should We Steal?

- Change your narrator and point of view when necessary. Sure, you have to change the focal character if you are switching, for example, from a chapter about James Bond to one about the bad guy. (Unless they’re in the same room.) But don’t overlook the effect you can have on a reader if your narrator changes in a less obvious manner.

- Think of some of your stories in terms of classic forms. Are you really writing a myth? A Biblical parable? An epic poem? If you are, you may want to consciously draw inspiration from the originals.

- Allow your reader to decipher the subtext of your piece. Yeah, so this story is chock-full of Catholic/Christian imagery. O’Connor doesn’t beat you over the head with it, though, making the connections to the New Testament more organic.

Short Story

1953, Flannery O'Connor, Point of View