Title of Work and its Form: Speak, novel

Author: Laurie Halse Anderson (on Twitter @halseanderson)

Date of Work: 1999

Where the Work Can Be Found: Speak can be found in all local independent bookstores, including Oswego, New York’s the river’s end bookstore. (Ms. Anderson is a friend of that particular store, as well!) You can also purchase the book online from Powell’s.

Bonuses: Here is a cool interview in which Ms. Anderson discusses Speak and the effect it has had on readers for fifteen years.

Want to see Ms. Anderson speak about Speak?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Structure

Discussion:

Melinda is not having the best year of her life. That’s to be expected, of course; the young woman is just entering high school. Unfortunately, Melinda has more to worry about than Homecoming and classes. The summer before, she was at a party and found it necessary to call the police. Her old friends are not very happy with her now and she has learned what it feels like to eat lunch alone. Speak chronicles the events of Melinda’s first year of high school. She makes friends with Heather, who loves to make plans. She loves Mr. Freeman’s art class, even if she doesn’t always know how much it means to her. She loves her overworked parents, but Melinda’s secret is making it hard for her to, well, speak to them…or anyone else. By the end of the book, Ms. Anderson reveals the secret and describes how Melinda achieves agency and takes charge of her own life and emotions.

It’s time to do some statistical analysis on the book. I know…I know. We became writers so we wouldn’t have to do math. Too bad; the numbers will help us figure out what Speak can teach us about writing. Like I said, the book takes place over the course of a whole school year. There are four sections, each of which are devoted to one of the year’s marking periods:

| Marking Period |

Pages the Marking Period Occupies in the Book |

Number of Pages |

| 1 |

1-46 |

47 |

| 2 |

47-92 |

45 |

| 3 |

93-139 |

46 |

| 4 |

140-198 |

58 |

What do we notice? Why, the first three secti0ns are virtually the same length! Interesting! The final section is the longest, by far. This is a big deal because the last section SHOULD be the longest. Ms. Anderson spends 139 pages setting up a lot of conflicts and putting a lot of balls into the air:

- What happened to Melinda at the party?

- Why won’t she “speak”/stand up for herself?

- Why does Melinda refer to Andy Evans as “IT?”

- Will Melinda make peace with her old friends?

- Melinda seems to like art…will she stop being frustrated with her art and create a cool piece?

If Ms. Anderson doesn’t answer all of these important questions (and more), we will feel pretty cheated, won’t we? The last section of the book is a little bit longer than the others because the author must pay off all of these conflicts. Explanations take a little bit of time, and they’re often the most satisfying part of a story. Think about the film Titanic. The director, James Cameron, devoted a LOT of that movie’s run time to the couple hours the boat was sinking, right? He did so because he made the same kind of promises that Ms. Anderson made and he needed to fulfill those promises.

Have you ever gone on a vacation? You had to prepare for the vacation, right? You had to pack your bags and save money and maybe even book a flight. This preparation wasn’t the most exciting part of your week off, was it? But when you got to your destination, you wanted to savor every moment. (Just like Ms. Anderson took her time in the fourth section of the book to make sure she answered every question we might have.)

These young kids sat in a car for thirty hours, thinking they were going to “Rattlesnake Ranch.” Their parents did all the preparation and set up the big moment when…they revealed the big secret. They were really going to Walt Disney World!

All those hours in the car may have been fun, but not as fun as the last part of the “story.” The same principle applies to writing. If you were to ask those little girls to write the story of their trip, which section would probably be the longest and most detailed? The Walt Disney World section, of course! The fourth section of Speak is the longest because the author took her time to give you the scenes you were really hoping for.

If you’ve read the book, you’re not a big fan of the character of Andy Evans. For over a hundred pages, you’re not sure why you hate him…you just do. Ms. Anderson couldn’t just tell you why Melinda is scared of Andy from the beginning. Why? Because Melinda wasn’t ready to talk about what happened. (That’s why the book is called Speak!) Instead, Ms. Anderson had to let you know he’s a bad guy in other ways. What are those ways?

- Melinda calls him “IT.” Upper-case letters, so you know she means business. And think about what it means to call someone “it.” They’re not even a real human being when you call them an “it.” Later in the book, she calls him “Andy Beast.” Same thing. Doesn’t sound nice.

- Melinda points out that Andy has a “short stabby name.” Why, that sounds like the kind of thing you say about a bad guy. Say some of the names from the book aloud: Melinda, Heather, Rachel/Rachelle…these all sound pretty calm and “pretty,” right? “Andy Evans” emerges a little sharper on the tongue.

- On page 90 of my edition, Andy arrives at the lunch table. Melinda says, “It feels like the Prince of Darkness has swept his cloak over the table. The lights dim. I shiver.” Again, that’s not the kind of thing you say about a person you think is nice.

- After page 90, Melinda starts mentioning Andy more and more. Page 108: Melinda is scared by the possibility that Andy sent her a valentine. Andy is “definitely not romantic.”

By the end of the book, when Ms. Anderson spills all of the beans, you REALLY know why you hate Andy. But the author keeps your attention and keeps you wondering by making Melinda talk about him the way she does. (Not to mention the fact that Melinda goes from not talking about him at all, to talking about him quite a bit!)

What’s the principle to learn here? Characterization isn’t just about letting us know what to think about a person you create. Characterization also drives the story. Our increasing dislike of Andy lets us know that Andy is pretty important to Melinda’s tale. We don’t know how he relates at first, but we get lots of clues.

It’s a small note, but I love that the book takes place in the Syracuse area. And not just because I grew up in the Syracuse area. Ms. Anderson makes the world of Speak feel real by describing the change of seasons and by populating the story with real landmarks: the big mall in Syracuse, the…interesting downtown retail climate, the dozens of feet of snow the area receives. If you really wanted to do so, you could find a map of Syracuse and chart Melinda’s course throughout the story.

More importantly, Ms. Anderson is making sure that we know her protagonist (the main character, the one who does things) is just like us. We live in a city with popular landmarks. We struggle with a specific kind of weather at times. The world feels real, doesn’t it? This is a principle called “verisimilitude.” That means “the appearance of reality in fiction.” Even though Speak is a made-up story, the book affects us more because it seems real and the events in the book could really happen. (Unfortunately, the central secret of the book happens all the time.)

One last thing. I happen to be finishing up my own Young Adult book (with another in the mental hopper) and I’m really glad that Young Adult books can deal with REAL LIFE issues that teenagers experience. When I was a young adult, I read Judy Blume books-they taught me about all kinds of “mature” subject matter. Unfortunately, Ms. Blume’s books are banned by parents and school administrators all the time. Even an important book like Speak is challenged and banned all the time. I LOVE that Ms. Anderson fights back against grownups who don’t want young people to learn about what people really go through. (Check out this awesome editorial she wrote. Can you tell that she’s all fired up?) My book isn’t THAT “mature,” but I do worry about being hassled by closed-minded folks if it ever gets published.

You might think that we’re made up of molecules and atoms and water and bone and blood. In a deeper sense, we are creatures made up of stories. The stories that we read and hear make us who we are. They teach us empathy for other human beings and light our way when we’re deciding what we want to do with our lives and how we wish to treat people. The next time you hear that someone wants to ban a book, remember: that person is trying to stop you from learning about the world and all of the people in it. After all, a book must be pretty powerful if grown adults are spending time trying to keep you from reading it…

What Should We Steal?

- Set up conflicts and devote a lot of page space to paying off those conflicts. There’s no hard-and-fast percentage of page space you must give to a certain conflict, of course, but it’s important that your reader feels fulfilled by the end.

- Employ characterization in such a way that it pushes the plot along. You will often hear that plot is derived from character. That’s true, but characterization can also advance the plot by itself and make the story seem more real, more “true.”

- Plop your character into a setting that seems real. Remember VERISIMILITUDE (the appearance of reality in fiction). When your characters go to a pizza place, why can’t they go to the same pizza place that you do? (I did this in my own Young Adult book!)

- Strike back against those who wish to ban books. The American Library Association will tell you all about this sad constant in American culture.

Novel

1999, Laurie Halse Anderson, Narrative Structure, Scholastic, Speak, Young Adult

Title of Work and its Form: “Islanders,” short story

Author: Kate Folk (on Twitter @katefolk)

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story debuted in the Spring & Summer 2014 issue of PINBALL. You can read the piece here.

Bonuses: Here is a short short story Ms. Folk published in Neon. Whoa…Ms. Folk had the honor of interviewing Joyce Carol Oates by e-mail. Here‘s how she and her colleagues rose to the challenge of asking Ms. Oates interesting questions that she hadn’t heard a million times. Want to see Ms. Folk read her work?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Stakes

Discussion:

This epistolary story relates the sad tale of an unnamed man who is still in love with Bonnie, the wife who apparently left him to throw herself into the arms of a “jobless artist.” Through the course of nine e-mails, we learn that the narrator is in the middle of a tense diplomatic situation; an island off the coast of a “strategic coastal sardine town” is drifting into the sea. There are two narratives here: the story of the conflict between islanders and mainlanders and that of the narrator’s seemingly futile attempt to work things out with Bonnie.

I love the efficient way in which Ms. Folk establishes the parallel narratives. The very first sentence introduces the personal conflict:

Don’t know if you’ll even read this email, as you are probably busy fucking your artist lover who has all the time in the world to spend with you due to having no actual job and leading the artistic lifestyle you always wanted for yourself…

The second paragraph establishes the crucial external conflict:

Supervisor Ross has sent me to this strategic coastal sardine town Re: Island Drifting Irretrievably to Sea. Tiny man-made island has floated a half mile off the coast for decades. In recent months, it has appeared more distant.

While this story isn’t a pure short-short, it’s still fairly brief; the author wastes no time establishing the situation and the inherent stakes involved. The narrator is coping with the painful loss of his wife and wants her back and a coastal community has been torn apart. We are more likely to care about these problems because Ms. Folk makes them clear from the beginning.

As I read the story, I wasn’t expecting to learn the name of the protagonist’s ex-wife. After all, how often do we use our significant others’ names when we write them e-mails? I did, however, love the way that Ms. Folk slipped her name into the story. The penultimate e-mail, sadly, was written while the narrator was drunk and particularly lovesick. He lies about being under siege, trying to convince his ex-wife that his life is in danger in hopes that the prospect of losing him will change her mind about the jobless artist. Dissembling, he leaves his ex-wife with these words:

My one true love, my beautiful, sweet Bonnie!

What a graceful and natural way to slip Bonnie’s name into the narrative! We never learn his name; learning hers personalizes her and helps us understand how he really feels. Further, when we know someone’s name, we naturally feel closer to them. In this way, Ms. Folk simulates adding some of Bonnie’s voice to the story. Sure, the narrator probably did some crummy things, and we’re not happy that she seems to have taken up with the kind of slimy loser of whom we were jealous in high school (and college and after college). “Bonnie” humanizes the character very quickly.

You already understand the principle if you remember The Silence of the Lambs. (A must-see film.) Remember when Clarice and her Quantico friend, Ardelia Mapp, are watching the press conference in which the Senator asks the then-unknown kidnapper to return her daughter?

SEN. MARTIN

I’m speaking now to the person who is holding my daughter. Her name is

Catherine… You have the power to let Catherine go, unharmed. She’s

very gentle and kind - talk to her and you’ll see. Her name is

Catherine…

Clarice is moved by what she sees. Other trainees are all around her.

CLARICE

(whispers)

Boy, is that smart…

ARDELIA

Why does she keep repeating the name?

CLARICE

Somebody’s coaching her… They’re trying to make him see Catherine as a person - not just an object.

Ms. Folk’s story is certainly very different from that of Thomas Harris and Ted Tally, but all three writers make great gains by using the simple release of a name to create powerful characterization.

What Should We Steal?

- Establish conflicts clearly, particularly in shorter pieces. If you’re writing an epic novel, you have a little bit of time before you risk losing the reader’s attention. Front-loading the conflicts and the stakes they create can immerse us in your piece very clearly.

- Name an otherwise tangential character to humanize him or her. What sets us apart from others more completely than a name?

Short Story

2014, Epistolary, Kate Folk, PINBALL, Stakes

Title of Work and its Form: “Coming to the Table,” creative nonfiction

Author: Allegra Hyde

Date of Work: 2014

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece made its debut in Flyway: Journal of Writing & Environment. You can find the piece here.

Bonuses: Try not to be jealous; here‘s a short piece Ms. Hyde placed in McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. Here is a brief interview Ms. Hyde gave to introduce herself as an editor for Hayden’s Ferry Review. Here is a short story she published in Superstition Review.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Beginnings

Discussion:

Ms. Hyde describes what must have been a fascinating time in her life. She was a first-year teacher in Eleuthera, “a skinny Bahamian out-island that dangles like a fishhook towards the Caribbean.” And she didn’t know how to cook. Her students at The Island School were very privileged, indded. Not only were they matriculating in what must be a breathtakingly beautiful place, but they were children of parents with means. One day, she and her students decide to cook a community meal sourced entirely from Eleutheran food. There were a couple hitches along the way-not the least of which was Ms. Hyde’s lack of confidence in her cooking ability-but students and staff alike enjoyed cassava-banana bread, fruit salad and pumpkin soup that contained just a hint of coconut.

I am sad to admit that I did not know about Eleuthera before reading the piece. I am well aware of where The Bahamas are located, but I hadn’t realized to which island Ms. Hyde was referring. Here’s the map extract from Wikipedia to orient us:

I think it’s pretty clear that Ms. Hyde’s first movement in the piece is an extremely important one. What’s her entry point into the story? A brief paragraph set apart from the rest of the narrative by

I think it’s pretty clear that Ms. Hyde’s first movement in the piece is an extremely important one. What’s her entry point into the story? A brief paragraph set apart from the rest of the narrative by

double spaces:

This is the situation: I am a first year teacher. I am a first year teacher at a remote environmental leadership school on the southern tip of Eleuthera, a skinny Bahamian out-island that dangles like a fishhook towards the Caribbean. I do not know how to cook.

What does Ms. Hyde gain by opening her story thus? She could easily have started off with a variation of her second paragraph:

Arriving at The Island School in 2010, I knew there would be challenges. Sunburns. The occasional jellyfish sting. Dormitory duty. But this all seemed like background noise given the opportunity I had to help students re-examine their relationship with the environment, to use the school’s own operations – which showcased methods of green living from solar hot water to biodiesel vans – as a model for inspiring a more sustainable future.

So why begin with that example of extreme narrative intrusion?

- It’s a great icebreaker and introduction. Ms. Hyde is not yet a big-time author whose accomplishments are known to the vast majority of readers. (This state could easily change, of course!) This first paragraph tells us all we need to know about Ms. Hyde to enjoy the story and does so very efficiently.

- The first paragraph is very inviting; the diction makes us feel as though Ms. Hyde is standing before us at a cocktail party, telling us an interesting and heartwarming tale.

- The complication is introduced immediately: the author claims she can’t cook…this is a story about how she took on the responsibility of coordinating and cooking a big meal.

- The setting is introduced very quickly and we’re transported to a place we’ve likely never been.

So why not begin in such a manner? Ms. Hyde seems to enjoy these “buttons,” these interjections that are given their own paragraphs. She employs the technique a few times through the course of the piece, including:

- “I never guessed that my culinary limitations would be a hurdle. I was a teacher, not a chef.”

- “It was against this backdrop that the campaign for One Local Meal began.”

While many of these interjections could simply be appended to the paragraphs that precede them, Ms. Hyde amps up the humor and reinforces the strength of her thought in these places. Most of all, it’s important to remember that we have a narrator for a reason. (Even when we’re writing about ourselves in the first person.) It’s the narrator’s job to keep the story humming and to contrive sentences in words in such a manner that we pay attention and understand.

I must say that I found one of Ms. Hyde’s choices very interesting. Her students themselves are not named or described outside of simple markers: “a glossy-haired girl.” When the author introduces local farmers and experts in Eleutheran flora, she gives them names and backstories. Now, Ms. Hyde could simply be protecting the identities of her students. That would be just fine by me. But I like to think that these choices help the reader understand what and who are most important; sure, the students are learning and enjoying a great meal. The “lower-class” characters, however, are much more interesting in the context of this piece. I loved meeting Monica Miller, a local farmer and Elidieu Joseph, an immigrant stonemason who knows best how to put wild Eleutheran plants on the plate.

The point is that we need to understand that we can’t inject every bit of knowledge we would like about the world we’re creating. Instead, we must tell the reader what they need to know in order to enjoy the greatest emotional impact.

What Should We Steal?

- Empower your narrator to do its job. It can be hard to decide where to begin a piece and where to put our sentences so that they have maximum effect…but that’s why you have a narrator.

- Offer more and deeper descriptions of the characters who are most important to the narrative. I’m finishing up a Young Adult novel (hopefully). I can’t devote pages of backstory to EVERY character…I need to tell the reader what they need to know about each of my creations.

Creative Nonfiction

2014, Allegra Hyde, Beginnings, Eleuthera, Flyway: Journal of Writing & Environment

Short Story, Video

Laurel Gilbert, Michael Kardos, Ohio State, Star Wars, T.C. Boyle

Title of Work and its Form: “I Heart Your Dog’s Head,” poem

Author: Erin Belieu (on Twitter @erinbelieu)

Date of Work: 2006

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem appears in Black Box, Ms. Belieu’s 2006 Copper Canyon Press book. The Poetry Foundation has made the poem available on its web site.

Bonuses: Check out this great interview the poet gave to Willow Springs. Ms. Belieu also conducts interviews with poets. Want to hear Ms. Belieu read her work? (Sure, you do.)

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Subject Matter

Discussion:

Poems have to be all dark and depressing, right? Don’t poems have to illuminate the author’s saddest thoughts? Appropriate subject matter for poems: romantic break-ups, deceased pets and the worst day you ever had…right?

Of course not! Poems can also be fun and can deal with any subject under the sun-or beyond. Ms. Belieu’s free verse poem is about her reaction to watching Bill Parcells coach a game on television. Now, the poet makes it clear she doesn’t care about football, but she understands that football, like everything else, is a chapter in the vast narrative of our society. After discussing her antipathy for Mr. Parcells, Ms. Belieu reveals her history of not caring about football despite having been born in Nebraska, one of the places where football is a particularly prominent part of the social fabric. The thought leads her to recall the barking Chihuahuas on her street. Finally, Ms. Belieu “puts her faith” in reincarnation, hoping that Mr. Parcells is someday “trapped in the body of a teacup poodle” so she can hear his yapping.

I loved that Ms. Belieu wrote a poem about a popular subject. Too many folks think that poems must be inaccessible and must deal with “fancy-pants” topics…not so! Football is the same as any other human endeavor; poets have the right to take a look at the sport with the full power of their critical acumen. I have done the same on occasi0n, writing poems for my blog on my favorite Ohio State sports site. (Why do I write poems for a community that is sport-centric? Well, poetry belongs everywhere and we shouldn’t assume that a “sports fan” doesn’t like what we do.)

The overall point is that we have permission to take on any subject we like. Football, computers, cars, Kardashians, the latest episode of Hell’s Kitchen…they’re all within our purview as artists. More importantly, we SHOULD interact with the rest of what is happening in our culture. Writers are the people who make sense of the world; we chronicle the evolution of the human soul.

Even better, Ms. Belieu doesn’t make the poem solely about football. Everything that we do means something more than is apparent on the surface, right? Just before the final stanza, she builds upon her football- and Chihuahua-related discussion. Why were those lines important? Well, they led her to think about “what’s wrong with this version of America.” She engages in cultural criticism, seeming to raise issues regarding the tribalism inherent in sport (Go Bucks!) and perhaps the obligation people feel to like a team just because their parents did. People like Bill Parcells, who she feels is happy and successful for the wrong reasons, will win the game, in spite of his sins. (Are you curious as to whether Mr. Parcells won in the game to which Ms. Belieu refers? Me too. Well, Mr. Parcells left the Jets in 1999 and returned to coaching with the Cowboys in 2003. At the time, the Giants and Jets shared Giants Stadium, part of the Meadowlands Sports Complex. The Cowboys played the Giants in Week 2 of the 2003 season. The score? Well, Mr. Parcells and the Cowboys won the game in an overtime thriller, 35-32.)

A writer can’t simply tell a story or provide his or her reader with a bare description of something; it’s our job to explain what that thing means. That single game is now pretty irrelevant, relegated to the memories of those who attended and to box score statistics. Thanks to Ms. Belieu’s insight, however, that 2003 game can still have a big effect on us. After all, we read the poem and it had some impact upon us!

I’ve been wracking my brain as to why Ms. Belieu made a specific choice in the poem. Approximately halfway through, she writes:

…of breaking a soul. Yes,

there’s the glorification of violence, the weird nexus

knitting the homo, both phobic and erotic,

but also, and worse, my parents in 1971, drunk as

Australian parrots in a bottlebush, screeching…

Look at that middle line. I love the way she condenses two words that are somewhat long and unwieldy. Instead of burdening the line with both “homophobic” and “homoerotic,” she is using language in a somewhat playful way and is inviting us to do the same. As I said, I do wonder why she cast the line that way. Why not:

knitting the homophobic and homoerotic

Well, as I said, I like the fun use of language. But why did she use commas when she could have used em-dashes?

knitting the homo—both phobic and erotic—

Or parentheses? After all, that second clause is a parenthetical statement.

knitting the homo (both phobic and erotic)

I’m certainly not criticizing Ms. Belieu’s choice; I’m just trying to understand the effect the choice has so I can use it in my work in the future. I think that the commas keep the poem flowing more fluidly than parentheses would. (A parenthetical thought might stop the reader for a moment. Didn’t this parenthetical thought stop you just a little?)

The lines that contain that fun sentence benefit from the slipperiness of the comma instead of the businesslike interjection of parentheses.

What Should We Steal?

- Empower yourself to confront any element of the human experience. There can and should be poems (and stories) about everything that has an effect on human beings.

- Add relevance to something that may seem irrelevant. I’m a big baseball fan and I love my Detroit Tigers. The Tigers play 162 games a year (not including the playoffs). It’s hard for me to remember a game a week after it’s played; the ones that endure in my memory are the ones to which I applied a special significance.

- Contrive your lines with the sounds of the words and phrases in mind. Even if you’re breaking a grammar rule or two, your higher duty is to communicate your thought to the reader in the most efficient way.

Poem

2006, Copper Canyon Press, Erin Belieu, Ohio State, Subject Matter

Title of Work and its Form: “Falling,” poem

Author: James L. Dickey

Where the Work Can Be Found: “Falling” has been anthologized about ten trillion times. You can also find the poem on the Poetry Foundation web site.

Bonuses: Here is Mr. Dickey’s New York Times obituary. Here is an interview Mr. Dickey gave to The Paris Review. What did the poet hope would happen when people read his work? Check out his answer:

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Punctuation

Discussion:

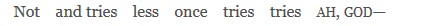

This “long” and fun poem tells a real-life story: that of a stewardess who fell out of a commercial airplane, meeting an unfortunate end at the hands of physics and fate. The poem begins as the woman is rummaging for blankets and completing her commonplace duties. Without warning, she is sucked out of the plane and falls to the earth. The plot of the poem may be simple, but it packs a big wallop because of the way Mr. Dickey uses language to describe her actions and thoughts as she endures what she learns will be the last couple moments of her life. The free verse work is split into seven stanzas that increase in intensity, culminating in a chilling final line:

There’s SO MUCH to learn from this poem that I should just jump right in, but I can’t help but point out one reason I’m writing about “Falling.” We all love Stephen King, right? Well, he gave an interview to The Atlantic‘s Jessica Lahey in which he discusses his views on craft and teaching. During a discussion regarding which kind of work has the biggest impact on young readers, Mr. King says:

When it comes to literature, the best luck I ever had with high school students was teaching James Dickey’s long poem “Falling.” It’s about a stewardess who’s sucked out of a plane. They see at once that it’s an extended metaphor for life itself, from the cradle to the grave, and they like the rich language.

Mr. King, of course, is correct in his assertions and “Falling” is the kind of poem we should all have under our belts.

What do we notice first of all? Well, Mr. Dickey stole the idea of the poem from a real news article. This one, in fact. Unfortunately, Mr. Dickey is no longer with us, so we can’t ask him about his exact motivation. It’s safe to say, however, that Mr. Dickey was probably struck by the terror and freedom the young woman experienced during her descent. Why shouldn’t you do the same thing? The next time you read a news story that strikes you, why not jot down a few lines. After all, most of us are moved by news stories and anecdotes we hear and the like. We’re never at a loss for inspiration if we make use of the infinite number of stories that surround us. There are also infinite angles you can take when borrowing from the news. You can simply retell the story. Or you can set the events 500 years in the future. Or you can devote the narrative to an observer. Or you can do as Mr. Dickey did, delving deep into what he imagined the stewardess was thinking and doing as the surly bonds of Earth reclaimed her.

And now, it’s time to do a little counting. I know…I know…so many of us become writers because we don’t want to deal with a ton of numbers. Unfortunately, statistical analysis can help us understand what makes “Falling” so effective. You’ll notice that Mr. Dicket doesn’t cast his lines in a traditional manner. That’s just fine, of course; the fragmented run-on lines mimic the stewardess’s mental state. I’m betting that it’s pretty hard to form coherent sentences when you’re at terminal velocity without a parachute.

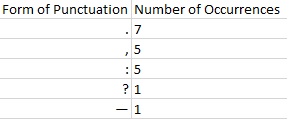

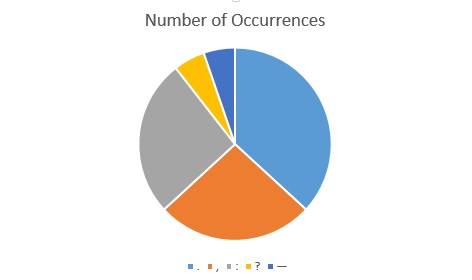

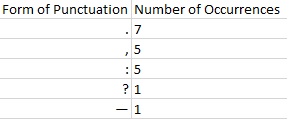

Mr. Dickey still had an obligation to help us figure out how we should split up the lines. And he also has the responsibility to let the reader take a breath. (We don’t want people to pass out at poetry readings, do we?) So how does he manipulate the prose to allow respiration and to communicate the feeling of disjointed thought? Well, you see all of those spaces in the fairly long lines. But you’ll notice that he also uses punctuation, albeit sparingly. Here’s a table that breaks down his use of punctuation in the poem:

Want to see the data in chart form?

Want to see the data in chart form?

Only 19 punctuation marks? In such a long poem? Crazy!

Well, not really. Mr. Dickey used the punctuation like spice, placing the marks only where they were utterly necessary. You’ll also notice that the end of the poem-the time when the character is most despondent, we might assume-only includes two marks, including the one at the very end. By that time, Mr. Dickey has taught us how to read the poem; he doesn’t need to provide the kind of guideposts that were much more of a necessity earlier in the poem. What’s the overall point? We must string together words in the manner appropriate to the work and mortar them together with the proper punctuation…even if that means omitting the marks altogether.

Another great thing about the poem is that Mr. Dickey actually gives the fictionalized protagonist things to do. Now, the unfortunate real-life stewardess may not have imagined she could save herself by diving into water. She may not have removed her jacket and shoes on purpose (or at all). It’s sad, but we have no way of knowing what she was thinking because she wasn’t around to tell us the next day. One of the big problems that a lot of people have when they fictionalize a real event is a lack of imagination. (At least, this failure is certainly a problem for me!)

When we are molding creative works, we shouldn’t forget that we can change anything we like about the characters and the plot. What a freeing notion, right? Like me, you may think of the perfect thing to say to someone…an hour after you should have said it. These restrictions are loosened in creative writing. By all means, if you are writing about your childhood, your best friend doesn’t have to live next door. Your first boyfriend or girlfriend doesn’t have to break your heart and show up to school looking blissful the next day. It’s not entirely necessary that your parents got divorced. Why? The characters aren’t really your best friend, significant other or parents. It’s your world, friend. You get to decide what joys and pains your characters endure.

What Should We Steal?

- Write your own version of a true story. What was going through the minds of American sailors during the attack on Pearl Harbor? What were the Japanese kamikaze pilots thinking?

- Shape your lines and use punctuations according to your needs. If you are trying to craft breathless lines for a breathless character, you might not want to use a lot of periods. (Periods are also called “full stops.” Stopping certainly wouldn’t be a good idea for this kind of character.)

- Feel empowered to fictionalize real-life situations. You are your characters’ puppet master. Pull the strings. But don’t take my word for it. Take the advice from Bela Lugosi:

Poem

Classic, James Dickey, Punctuation, Stephen King

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

Ravi Mangla is a very successful gent. In addition to his Outpost19 book, Understudies, Mr. Mangla has placed his work in some very cool journals, including Mid-American Review, American Short Fiction and Wigleaf. He’s also written for BULL Men’s Fiction, a personal favorite of mine.

Now, we could be overwhelmingly jealous of Mr. Mangla, but jealousy is an emotion suitable only for country songs. It would be far more profitable for us to enjoy his work and to try and learn from what he does well. You may wish to share a nine-hour phone call with him in which you ask only one question and expect him to answer. But if Mr. Mangla offered such a service, he would have no time to write! Instead, Mr. Mangla has been gracious enough to offer his insight into some of the small decisions he made in “Feats of Strength,” a short short he published in Tin House‘s Open Bar blog.

1) “Feats of Strength” features two lines of dialogue. One happens in present tense-the strongman commits to buying the car-and one happens in the past: Natalie wonders how she and her husband could have been so negligent as to purchase a defective baby crib.

Why did you put the spoken lines into italics instead of using the good, old-fashioned quotation marks? How come you did the same thing for both lines of dialogue, seeing as how one took place in the past and the other took place in the present?

RM: Dialogue is a bit of a spoiled brat, demanding not only distinctive markings but an entirely new paragraph (soon it will be asking to be underlined). Aesthetically, I don’t find the appearance of quotation marks particularly pleasing. Whenever possible I use plain text or italics. Only if the clarity is compromised will I roll out the quotes.

2) About 55% into the story, you have the first person narrator tell us the name of his child:

“-his name is Dev, by the way-“

Why didn’t you just write, “my son, Dev” instead? The clause that names Dev breaks up a sentence and also seems like more obvious and brash narration than the rest of the piece. Why’d you do it that way?

RM: I hoped it would lend some naturalism to the piece. The omission of the child’s name until late in the story suggests a fallibility on the part of the narrator. In a piece like this, with a contrivance like a strongman at its center, I have to work twice as hard to keep the reader from seeing the strings. Sometimes a small disruption, a note of dissonance, can disarm the reader and help them to buy into the narrative.

3) The strongman decides to bring his new car home in an unorthodox manner. Instead of just driving it home, he gets some exercise by pulling it there instead. You tell the reader:

“With a tow hook, he attaches a thick rope to the underside of the front bumper.”

The sentence seems to be pretty simple and declarative. Why did you put the clause with the tow hook at the beginning of the sentence? Why not just write,

“He attaches a thick rope to the underside of the front bumper with a tow hook.”

RM: I chose that phrasing solely for the sake of sentence variation. The previous sentence started with he, and I was hesitant to replicate it. I don’t want the sentences to become too predictable or monotonous.

4) In the final paragraph, the family waves goodbye to the now-inconvenient automobile. You write:

“The strongman reaches a bend in the road, disappears behind a cluster of trees.”

Why’d you remove the conjunction (I’m guessing you would choose “and”) and plop in that comma?

RM: Often I’ll exclude a conjunction between clauses for rhythm. It sounds jazzier to me (but perhaps not to every reader). It’s a habit I picked up from reading Sam Lipsyte. I’m a huge admirer of his language craft. His sentences have such a unique cadence.

[Editor’s Note: Mr. Mangla makes a good point. If you’re not familiar with Sam Lipsyte’s work, why not check out this New Yorker story he wrote. Or one of his books? You get the drift.]

5) The story is bookended with appearances from “several women in the neighborhood” who sit in their yards and watch the scene. You don’t mention them elsewhere in the story and they don’t affect the narrative directly.

Space is at a premium in a short short. This story is 671 words long. Why did you devote 27 words-slightly more than 4% of the text!-to the women? What, in your mind, is their function?

RM: They exist to underscore the strangeness of the scene. If there was a strongman lifting a car in my neighborhood, I know I’d be standing around watching. I think they also help to open up the world of the story, so the scene isn’t happening in a vacuum.

Ravi Mangla is the author of the novel Understudies (Outpost19, 2013). His work has appeared in Mid-American Review, American Short Fiction, The Collagist, Gigantic, The Rumpus, Wigleaf, and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. Follow him on Twitter: @ravi_mangla.

Short Story

2014, Outpost19, Ravi Mangla, Tin House, Why'd You Do That?

Title of Work and its Form: “Perspective,” poem

Author: Laura Kasischke

Date of Work: 2012

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem debuted in Volume 32, Number 4 of New England Review. Denise Duhamel and David Lehman subsequently selected “Perspective” for The Best American Poetry 2013 and you can find the poem in that anthology.

Bonuses: This New York Times review of The Raising will make you want to pick up the book. Here is a poem Ms. Kasischke published in Poetry.

Want to see Ms. Kasischke’s appearance at the 2012 National Book Festival?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Similes and Metaphors

Discussion:

Ms. Kasischke’s poem is a fantastic example of the way in which a work of literature can be intensely personal to the author and audience alike. The first three stanzas of the poem consists of comparisons related to massive upheaval and emotional epiphany. After polishing up his or her lens, the narrator of the poem now understands the reality of the situation with respect to an unnamed “you.” Simple and graceful and beautiful.

So what can we steal? Well, look at the technique Ms. Kasischke uses in those first three stanzas. They’re a collection of similes, aren’t they?

- “Like the lake…”

- “Like the Flood…”

- “Like the sheet…”

- “Like the sheet…” (it’s a different sheet in a different situation.)

Ms. Kasischke is also a little coy with the other half of the comparison, allowing you to fill in the blanks with something related to your own life or experience. So why can’t we write a poem in which we make repeated comparisons in order to describe a situation or character. For example, who is…

“Faster than a speeding bullet. More powerful than a locomotive. Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound…”?

Why, it’s Superman, of course. If you didn’t know about him before, you have a great idea of his powers after absorbing all of those metaphors.

If we want to stay with similes, we can toggle over to “as.” How long will you love someone who is special to you? For example:

As around the sun the earth knows she’s revolving

And the rosebuds know to bloom in early May

Just as hate knows love’s the cure

You can rest your mind assure

That I’ll be loving you always

Oh…Stevie Wonder beat us to that idea.

But that’s okay. (Especially because Stevie Wonder is so incredibly talented and awesome.) You can create your own list of similes or metaphors that will, through repetition, create a powerful rhetorical response in your reader.

Ms. Kasischke splits the poem (in my view) into two explicit sections. The first three stanzas establish that something has changed in the narrator’s mind; he or she has reached some epiphany. The second half describes the method by which this result was achieved: “The polished lens.” Then the narrator informs the other person involved that he or she now knows the truth and that their relationship has changed. First section: expression of understanding. Second section: establishing consequences.

How did Ms. Kasischke make the transition so clear? She could have easily split the poem into explicit sections:

I

Like the lake…

…

II

And the sudden…

What did Ms. Kasischke gain by structuring the poem the way she did? Well, I love the way the poem flows. In this case, the “I” and “II” stop our eye and would be a bit of a roadblock to our progressive understanding of the poem. (You are free to disagree, of course!) Still, Ms. Kasischke did not leave us adrift; she made it very easy for us to understand what she was doing. How?

In the first three stanzas, Ms. Kasischke begins with four similes that employ “like” and then breaks the pattern with two more that omit “like.” The pattern has broken down…there must be something new coming. Further, the poet directly references a narrative and its “end” (in addition to its non-linear nature).

The next stanza pays off the hint of something new: “the sudden sense./ The polished lens.” The lines are different and there are no more uses of “like.” In fact, Ms. Kasischke even switches to “as if.” And then there’s that “you,” a HUGE move considering that we learn the poem is now directed at a specific person. We imagine this must be a separate section with a different intent.

See how we figure all of this out without being told in an explicit manner?

One last note…not a big one. Ms. Kasischke capitalizes “Flood” in the fourth line of the poem. I spent a couple of seconds wondering why. Now, the author may have a completely different idea-which is perfectly fine-but I think that the capital F is a reference to one of the creation story floods that you find in so many mythologies around the world. (I don’t want to assume which specific religion Ms. Kasischke might mean. You know what happens when you assume. You make an assu out of me.)

No matter which mythology she might be referencing, Ms. Kasischke, with the simple capitalization of a letter, ties the work into big-time stories that many people hold very close to their hearts. I guess I’m not the only one who feels bad for an insect in the sink, a creature who just can’t understand why a tidal wave is overtaking their safe haven. The fly is confused and hurt and scared. The same way that everyone but Noah and his family members must have felt during the Flood in the Old Testament. See? Choosing “F” instead of “f” has made me think about huge ideas.

What Should We Steal?

- List similes and metaphors to establish situation, emotion or character. Like a pound puppy who is brought home by a loving family, I’m grateful for all of my Great Writers Steal fans.

- Create sections in your work without section breaks. What are some other ways that you can create the effects we earn from big transitions without flat-out telling the reader you’re making a big change?

- Small changes in text can have big and meaningful ramifications. A capitalized letter or switch from a period to a semi-colon can give your work a whole new depth.

Poem

2012, Best American Poetry 2013, Laura Kasischke, New England Review, Similes and Metaphors

Title of Work and its Form: “I take your T-shirt to bed again…,” poem

Author: Amy Lemmon (on Twitter @aSaintNobody)

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem debuted in Vitrine: a printed museum and was subsequently chosen for The Best American Poetry 2013 by the great Denise Duhamel and David Lehman. You can find the poem in the anthology-a book we should all have-but Ms. Lemmon was kind enough to post the poem on her blog.

Bonuses: It’s no secret that Ms. Duhamel is one of my favorite contemporary poets; check out the poems Ms. Duhamel and Ms. Lemmon wrote together for Superstition Review. Why not check out Saint Nobody, Ms. Lemmon’s Red Hen Press book? Want to see the author read her work?

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Efficiency

Discussion:

This thirteen-line poem is cast in the first person and the narrator is addressing a lover who won’t return for three days. (Although I suppose it would be funny if the poem, drenched in beautiful romantic imagery, were about a postal carrier or a clerk at the supermarket. We never like to say that there’s any one right answer in literature, but it’s safe to say that the narrator is thinking about his or her lover.) In an attempt to feel closer to the absent lover, the narrator has tried to mimic their scent and fantasizes about the imminent homecoming.

This may be a GWS first: I stole a technique from “I take your T-shirt…” for one of my own poems and the piece was just published in the East Jasmine Review. I admired the way in which Ms. Lemmon opened her poem:

I take your T-Shirt to bed again…

and by now it has almost lost its scent-

Why did I like the way that Ms. Lemmon ended the title with an ellipsis, how she treated the title like any other sentence?

- The move bridges the gap between the title and the body of the poem. I don’t know about you, but these two elements sometimes seem separated. Not so in this work.

- It can be hard to come up with a title…not so if you kick off a poem with its first line.

- The reader is placed into a familiar mindset: he or she is reading a first person story. When we read that “I,” we are automatically relating in a deeper place as human beings.

- The title establishes what kind of poem this will be. This is not blank verse. It’s not a sonnet or a villanelle. Ms. Lemmon lets us know that this is a free verse poem very quickly, answering one of the questions that may be on our minds before we can ease into the enjoyment phase of reading.

In case you are curious, I began my poem, “When you called,” and eased into a sad narrative about a bad parent who calls their child…once in a while. Feel free to decide for yourself what my work means, but the point is that I think I gained some of the same advantages Ms. Lemmon enjoyed in her poem.

What do you notice about the shape of the poem itself? Well, the lines get a little bit longer. What do you notice about the language? It’s a little less focused than at the beginning of the stanza. Why? Well, here’s my interpretation. After thinking about and pining for his or her lover, the narrator is feeling a great deal of sexual arousal. If we can keep it real, this state renders most people a little more instinctive and emotional than they are intellectual. Our communication is not necessarily less effective than when we’re not thinking about sex, but we’re more likely to speak in different tones and in different nonverbal ways. The poem changes to reflect the altered mental state of its narrator. What are some of the changes?

- The last line is the longest in the poem

- The narrator employs a delightful homonym pair, “pores/pour,” that pleases us in a base instead of intellectual manner

- The clauses are very short, just like the thoughts most of us have when aroused

- We see the first use of italics in the poem; typographical tricks are to prose what nonverbal communication is to speaking

The first person narrator’s mindset is very clear because Ms. Lemmon informs our conscious and subconscious about the changes. The same principle is used in the end of the poem. An em-dash sends us off into the world, inviting us to come up with our own idea of what happens next for the narrator and the lover in question. Ms. Lemmon, like Ms. Duhamel, uses language beautifully and fulfills all of the requirements of “literary/smarty-pants” poetry, but keeps her work accessible to folks who may not read poetry very often. (I happen to teach a lot of these folks; they love poetry but just don’t know it.) This poem accesses feelings that are deeply held inside us all and uses language in a way we can all understand to depict sexual and romantic longing.

What Should We Steal?

- Make your title part of the body of the work. A title can be a summation and a beginning at the same time: an economical and powerful way to start.

- Alter your lines and sentences to reflect the mental state of the narrator. If you just went for a two-mile run, you’re not going to be able to rattle off long, complicated sentences very easily. Nor should your characters.

- End a work in guided ambiguity. I have an idea as to what the narrator will do next because Ms. Lemmon gave me so many clues; your idea is equally valid.

Poem

Amy Lemmon, Best American Poetry 2013, Efficiency, Vitrine: a printed museum

Can we be honest? Most writers like attention and enjoy being part of a dedicated literary community. I am certainly one of these writers. The GWS Click Bait Controversy is designed to bring attention to an important issue that impacts us all. (And to GWS.) The provocative title is designed to make you click. (I thought about photoshopping a picture of Thomas Hardy on a date with Kim Kardashian to get your attention.)

You have likely read Nicholas Carr’s excellent 2008 Atlantic article, “Is Google Making us Stupid?” If you haven’t, go check it out right now. Mr. Carr describes one of the biggest problems of our increasingly digital lives: we’re losing the ability to read long works of fiction and nonfiction. We’re skimming and scrolling to find the important parts so we can-oops, I got a text. What was I saying?

Carr illustrates, in a calm and convincing manner, how our brains are being shaped by the media we consume. Has this always happened? Yes. Is it necessarily a bad thing? Yes and no. We live in a fantastic time; virtually the whole of human knowledge is available at our fingertips, but we’re increasingly ignoring depth and breath, content to wade in the shallow waters of the shiny and superficial.

How does this relate to fiction? I’m not THAT old, but I’m also no spring chicken. I remember the days before literary journals accepted electronic submissions; I did my time at the post office, explaining what an SASE is and why I didn’t seal the manila envelope before I brought it to the counter. This may only be my perception, but I do believe that flash fiction has seen an amazing increase in popularity in the twenty (geez, twenty!) years since the Internet entered our daily lives. There are countless online literary journals, most of them excellent, of course. These journals often feature stories whose word counts are far lower than those seen in the grand paper journals we know and love: The Kenyon Review, Ploughshares, Tin House…you know, all of those awesome journals that seed Best American each year.

Why are short short stories so popular now? There are lots of reasons:

- The best of them demonstrate powerful narrative economy. They feature a beginning, middle and end…all in 400 words. The characters manage to be far more realistic and human than really should be possible in so little page space.

- The form appeals to our “busy” lives. As the wonderful SmokeLong Quarterly points out, their stories can be read in the time it takes to have a smoke.

- Reading on a screen (computer or smartphone) is just not as appealing as reading an old-fashioned paper page. No matter what some undergrads claim, it’s just not realistic to read Les Miserables on a phone. Short shorts don’t tax our attention span or eyeballs.

- Short shorts take less time to write than “conventional” short stories. (That’s usually the case, anyway.) A writer who is struggling with a fifteen-page manuscript might find it easier to pump out one that is two pages instead.

- Short shorts require lower levels of the stuff that makes up a narrative. Die Hard just wouldn’t work as a short short. (Unless you’re making a parody.) Justifiably, audiences don’t expect a long, sweeping narrative when they click on a five-inch-long story.

- Online literary journals, by virtue of the medium, make it easier to transform a short story into a work of art through typography, layout and all of those other graphic design skills demonstrated so ably by Paper Darts.

What’s the problem, you might ask. Who cares whether short shorts are becoming increasingly prominent? Well, this little essay is click bait, right? I’m trying to get people involved in a discussion, so I need to propose an argument that might be slightly controversial. (Or I need to change the title to “Justin Bieber dating Jane Austen? OMGLOL!?”)

So while I love (and write) short shorts as much as I care for any medium of human expression, we may need to confront some of the problems with the form of the short short.

Crummy clickbait sites are only in it for the clicks. If you look at the US Magazine web site, you’ll find each article is 100 words of boring with several pictures. And eight million links surround the boring. Sadly, this format is taking over “news.” It’s now possible to feel as though you “read the paper” if you clicked through the AP articles Huffpo borrowed. (The Onion‘s Click Hole offshoot does a wonderful job of lampooning these non-news news sources.)

Short shorts, like the vast majority of 100-word clickbait “articles,” simply can’t offer the same powerful and immersive reading experience as that of a longer work.

As I made clear in my (extremely long) essay on the work of T.C. Boyle, his “The Love of My Life” is one of my favorite short stories ever. This story is 7500 words long. Sure, you could write a 500-word story that serves the same themes and evokes a similar feeling, but it’s inescapably true that Mr. Boyle’s story is so powerful, at least in part, because of the length and detail of the story.

Now, you might follow the advice of Polonius and point out that “brevity is the soul of wit.” I’ll point out that performances of Hamlet can last up to five hours. The Dane’s great tragedy simply can’t be expressed in five minutes.

The increasing popularity of short shorts conditions writers to create miniature narratives that offer reduced opportunities for detailed plot and characterization.

As Carr affirms, the media that we consume shapes our cognitive function. He (and we) are more likely to skim when we read online because we’ve been reading and skimming online articles for so long. The proliferation of short shorts, it seems, could condition writers to turn from the “traditional” story in favor of what they spend more of their time reading.

Carr also points out that reading novels and longer pieces enhances our ability to understand and confront complicated situations. Could reading short shorts hinder our ability to create complicated characters and narratives? I love (most of) my short shorts, but I would be lying if I said that my short shorts are as powerful and meaningful as my longer work. (Your mileage may vary, of course.)

These are certainly not new concerns, of course. The transition from cuneiform to papyrus must have inspired thinkers to lament that the old ways were disappearing. Does TV rot your brain? Nah, I’m not that much of an extremist; I am primarily urging a balanced media diet and an acknowledgement that we can’t turn further away from the kind of stories that meant so much to us before the Internet became ubiquitous. The important thing is that we remain conscious with respect to how the media we consume shapes our tastes and the work we produce.

Writing short shorts often (not always) requires less skill and attention on the part of the writer, preventing the writer from acquiring the skills necessary to maintain a vast narrative over a much larger number of pages.

This point definitely comes with a big ol’ caveat: I agree that it often takes an awful lot of skill to cram a whole narrative into a small number of words. We have the famous example from Hemingway (possibly):

For sale: Baby shoes, never worn.

Those six words pack a big wallop, don’t they?

Still, the law of diminishing returns catches up with short narratives. Think of the piece of my own that I linked a couple paragraphs ago. So many questions are left unanswered! What are the reasons? I’m not the world’s best writer and I was working with a very small canvas.

If artists spend too much time working on a small canvas, how can they hope to give the world a Sistine Chapel ceiling or even a “Guernica?”

So…what is the solution? What am I urging people to do?

Well, the same inherent lack of self-esteem that prevented me from being too provocative with this essay also ensures that my dictates are wishy-washy.

Let’s discuss these issues! Whether you do so in the comments of this piece or elsewhere, share ideas that will help us restore the short story to the place of societal prominence it once held.

Let’s put more emphasis on longer short stories! Editors should be more willing to accept longer pieces and readers should justify this leap of faith by scrolling all the way through those stories!

Most of all, we need to exercise our brains and ensure that we don’t fall prey to the phenomenon that Carr discussed in his Atlantic article. I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to live in a future in which literary works become shorter and less complex in some ways.

But what do you think?

Short Story

GWS Click Bait Controversy