We all love Joyce Carol Oates for her beautiful and engaging work, for her steadfast advocacy of other writers, for her dedication to helping all of those who dare to turn thoughts into literature. Ms. Oates is also active on Twitter, yet another way in which she remains of prime relevance in our community.

Ms. Oates recently hit upon something that I think about a lot, even though it doesn’t apply to me in the least. As Shakespeare said through Cassio, our reputations are the immortal parts of ourselves and “what remains is bestial.” One reason that most of us bother to write at all is that we wish to ensure that some part of us may remain for many future generations. We hope that our stories and ideas may resonate hundreds of years from now, as Shakespeare’s do. Ms. Oates’s novels and stories will survive as long as humans crave stories (which is forever), but most of us will see our influence wane until it flickers and snuffs itself for lack of attention. (Out, out, brief candle!)

Ms. Oates reminded us of our temporary nature in a witty and Oatesian way, saying:

Ms. Oates name-checked some writers who have lost relevance in the canon over the past few decades:

Whatever the reasons, my heart went out to these writers, each of whom had the same dreams and goals and joys that are shared by every writer. They were also lucky enough to shape the community, for good and ill, through the generations of students who looked to them for wisdom and advice in the craft.

Other writers may be in the process of overwriting what they did during the twentieth century-such is the march of time-but let’s give a little attention to these writers, people who still have something to teach us.

To my shame, I had not previously read Howard Nemerov, but I am glad that Ms. Oates’s tweet did its job. Mr. Nemerov’s work, a nice sample of which can be found at the Poetry Foundation web site, is graceful and accessible in a way that demands a wider audience. A great deal of contemporary poetry, I am sad to say, seems contrived to confuse. Any time I have tried to introduce such work to young adults, they go away scratching their heads and checking their phones. When you show them a work such as Randall Jarrell’s “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” they go away thinking about the horrific nature of the ball turret gunner’s death and checking their phones.

Mr. Nemerov enjoyed working in forms and playing with meter and rhyme. (Another strike against him, it seems…) Judging from the sample I have enjoyed, Mr. Nemerov’s poems are relatable in the same way as those of Billy Collins: they often deal with parenting, aging and nature. These are subjects to which your non-writer (and perhaps non-reader) friends can relate, and Mr. Nemerov writes about them in a manner that these same friends can understand.

I suppose this is the first lesson we can take from Mr. Nemerov’s work. People love playing with language. They love contemplating where their life has gone and where it has been. Instead of cloaking our own profound thoughts in deliberately obtuse language, perhaps we should be more open to using meter and rhyme in a way that is accessible to those who have not yet earned their own MFA.

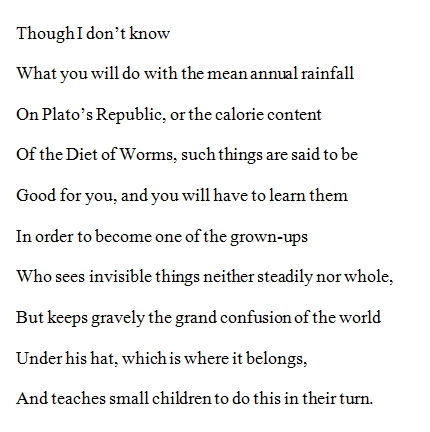

Let’s take a closer look at an extract from a poem called “To David, About His Education.”

What do we notice? Mr. Nemerov employs, in my view, a somewhat loose iambic pentameter in the poem. Unlike a more rigid example (“shall I comPARE thee TO a SUMmer’s DAY?”), the stressed and unstressed syllables are harder to identify. I wonder about the effect of this looser meter; are these lines more “accessible” to those who don’t yet realize they like poetry?

What do we notice? Mr. Nemerov employs, in my view, a somewhat loose iambic pentameter in the poem. Unlike a more rigid example (“shall I comPARE thee TO a SUMmer’s DAY?”), the stressed and unstressed syllables are harder to identify. I wonder about the effect of this looser meter; are these lines more “accessible” to those who don’t yet realize they like poetry?

You’ll also notice, for good and ill, that Mr. Nemerov’s use of meter forces him into making word choices. Look at that last line. Is “their” really necessary for us to understand what the poet means? I don’t believe so. Without that additional word, however, the meter breaks down. Where Mr. Nemerov is playful with the meter in much of the rest of the poem, he wisely ends it with a fairly solid line of blank verse:

and TEACHes small CHILdren to DO this IN their TURN.

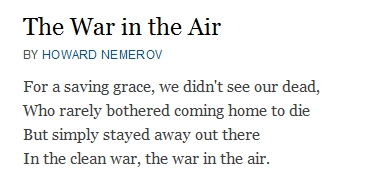

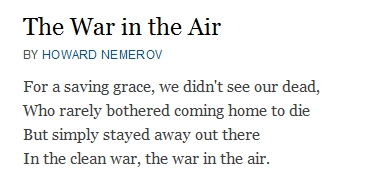

One of Mr. Nemerov’s more famous poems is “The War in the Air.” Here’s the first stanza:

It bears mentioning that Mr. Nemerov served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the U. S. Army Air Forces during World War II. Perhaps the first thing we notice is now Mr. Nemerov is playing with meter and rhyme. The first two lines of each stanza are cast in that “loose” iambic pentameter and the last two lines of each stanza rhyme.

It bears mentioning that Mr. Nemerov served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the U. S. Army Air Forces during World War II. Perhaps the first thing we notice is now Mr. Nemerov is playing with meter and rhyme. The first two lines of each stanza are cast in that “loose” iambic pentameter and the last two lines of each stanza rhyme.

Rhyme and meter are somewhat out of fashion today, but they will always be included in the poet’s toolbox. Why do I love that this poem follows some rules? The rhyme and meter contribute to the feeling of the poem. We can all agree that Mr. Nemerov saw some terrible sights during his time as a pilot and anyone who has spoken with a veteran knows that they took and still take what they did very seriously. The structure imposed by rhyme and meter, it seems to me, facilitate the kind of solemn reflection appropriate to the subject of the work.

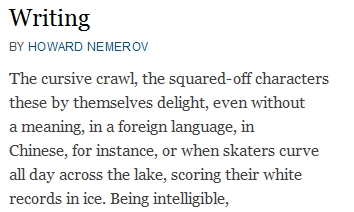

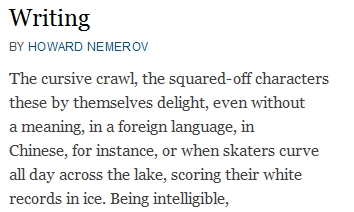

Like most writers, Mr. Nemerov reflected upon his avocation. Check out the beginning of his poem, “Writing”:

The first thing we notice is that the poet is adhering more strongly to the meter than was the case in the first two poems. Isn’t that image a beautiful one? Mr. Nemerov reminds us that everything about language is beautiful, including the very pen strokes we use to communicate our thoughts.

The first thing we notice is that the poet is adhering more strongly to the meter than was the case in the first two poems. Isn’t that image a beautiful one? Mr. Nemerov reminds us that everything about language is beautiful, including the very pen strokes we use to communicate our thoughts.

If nothing else, Mr. Nemerov deserves to be remembered for the decades of devotion that he gave to the writing community. Not only was he the Poet Laureate, empowered to spread the gospel of poetry far and wide, but he nurtured generations of poets as a teacher. So thank you, Ms. Oates, for reminding us of a writer whose name deserves to be on our tongues, if not for all time, at least a little longer.

Poem

Howard Nemerov, Joyce Carol Oates

Friends, David Chase’s HBO program The Sopranos is widely hailed as one of the shows that ushered in the latest “golden age” of television. James Gandolfini portrayed Tony Soprano, a New Jersey man who spent his time caring for his family and his waste management business. Oh yeah…he was also a big-time player in the Jersey mob.

The Sopranos ran from 1999 to 2007 and has influenced countless dramas that followed. (Breaking Bad, in particular.) The final episode was highly anticipated and Mr. Chase did his duty, giving the story an ending that viewers wouldn’t soon forget:

Many were confused by the abrupt cut to black. Others figured there was a problem with their cable connection. The reaction bummed me out a little; I loved that Mr. Chase ended the show on his own terms and that he made an artistic choice.

Didn’t Mr. Chase experience every writer’s dream? Millions of people were hanging on his every word and have since spent the better part of a decade deciding what the piece means to them. “Masterofsopranos” offered my favorite analysis. Jamie Andrew produced a thoughtful explanation for Den of Geek!

Well, Mr. Chase offered some after-the-fact clarification with regard to Tony’s true fate. I’ve linked an article, but you know what? It doesn’t matter what Mr. Chase thinks. He was kind enough to give us the work and it now belongs to each viewer.

Now, I know that Twitter isn’t really good for much. It is, however, a means of communication and must have some intrinsic value. For instance, the great Joyce Carol Oates offered some ideas regarding the Sopranos finale that we should bear in mind:

Ms. Oates retweeted this nugget of timeless wisdom:

Writing is a double-edged sword. Writers get the pleasure of sharing creations with readers…then the writer must accept that each reader invariably makes that creation their own. We thank Mr. Chase for giving us Tony and Paulie and Christopher and Carmela and Adriana (RIP), but his act of giving also means that they now belong to us.

Did Tony get shot? Your theory is worth just as much as the impulse that guided Mr. Chase during his long hours at the keyboard.

Television Program

2007, GWS Twisdom, Joyce Carol Oates, The Sopranos

Title of Work and its Form: “ID,” short story

Author: Joyce Carol Oates (on Twitter @JoyceCarolOates)

Date of Work: 2010

Where the Work Can Be Found: The story made its debut in the March 29, 2010 issue of The New Yorker. The kind folks at that publication have been kind enough to offer the story online for your enjoyment. “ID” was subsequently chosen for Best American 2011 and can be found in that anthology.

Bonuses: Here is what blogger Karen Carlson thought of the story. Here is a cool review and discussion of the story over at Perpetual Folly. Here is a Wall Street Journal article about Ms. Oates and the touching way in which she dealt with losing her husband, one of the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Perspective

Discussion:

You, kind reader, are witness to one of the worst days of Lisette Mulvey’s life. Thirteen-year-old Lisette had half of a beer before school; these things are easier when you have an absentee father and your mother often takes off for long stretches. The story chronicles a few hours in Lisette’s bad day, but Ms. Oates intertwines flashbacks and exposition with the dramatic present. We learn about Lisette’s crush on a boy and her mother’s poor behavior. Lysette’s mother works in the casinos of Atlantic City and seems to fit in with the seedier part of the AC culture. The officers (one male and one female) show Lisette a body in the morgue; the young woman doesn’t ID the body as her mother. The female officer tells her it’s all right; there are other ways to identify the woman who was found in a drainage ditch. The officers bring her to school, where Lisette tries to fall back into the comfort of her friends.

Ms. Oates is indisputably one of our American literary lionesses and has been at the top of her game for quite some time, with no end in sight. What is one of the million things that I love about her writing, and this story in particular? Ms. Oates produces work that is both of its time and timeless at the same time. In a way, she is like Alfred Hitchcock. No matter that Hitch was working with people from a different generation; he always produced films that felt immediate and spoke to anyone who saw them. Ms. Oates is the same way. You can tell that Ms. Oates has boundless curiosity because she knows how it feels to go to high school in 2010. She understands how a thirteen-year-old girl in 2010 feels about herself and her friends. As I get older and slightly wiser, I realize that I’m losing a little bit of this kind of knowledge. I haven’t gone trick-or-treating in more than twenty years. Could I really remember what it feels like? How to say this…romance has been a stranger for a while. Could I really depict young love with any fidelity? Ms. Oates would have no problem with these situations and emotions because of her deep understanding of humanity.

We’ve all heard that we should “write what we know.” Yes, that is good advice, but if we followed that advice with too much dedication, we would have no science fiction or horror or stories in which the nerdy guy gets the cheerleader. Ms. Oates points out in her author’s note that “ID” was inspired by the untimely death of her husband. A funeral director asked Ms. Oates to identify her husband’s body—she didn’t want to see it again. To my knowledge, Ms. Oates does not have first-hand experience of being a thirteen-year-old young woman tasked with identifying her dead mother. She does, however, KNOW what it is like to face the stark reality that the person you love is dead and to see their body in the morgue. We’re all human, right? It is more important to understand the emotional experiences that you are chronicling than to have first-hand experience on the topic. (Especially if you’re writing fiction, of course.)

When I was in high school, I wrote a lot of “high school” stories; I believe that’s perfectly natural. I certainly see a lot of “dorm stories” when my students turn in their work. (This tendency is perfectly natural, too.) We must remember that we have the license to write about anything we like. What fun would it be if we only write about people who are just like us who live lives just like ours? Boring!

Ms. Oates had a bit of a challenge in the story because she needed to get a lot of exposition into a story that is pretty much in real-time. As I pointed out, the exposition is woven in with the material that is in the dramatic present. Why aren’t these sections a bit of a roadblock? Why don’t they cause the reader’s attention to flag? Ms. Oates builds a ton of suspense into the story.

- Why do “they” want to see Lisette’s ID?

- “Some older guys had got her high on beer, for a joke.” Will Lisette’s drunkenness get her in trouble or complicate things?

- How will J.C. respond to the note that Lisette sent him? Will he break her heart?

- Mom doesn’t seem to be a very upstanding citizen. Complications?

- Uh oh. Two police officers want to see Lisette.

- Will the body turn out to be that of Lisette’s mother?

One reason the story is so very compelling is that the emotional and narrative foundation of the story is sprinkled in with grace and in such a way that Ms. Oates creates mysteries to which we want the answers! These “roadblocks” speed the reader along instead of holding them back.

What Should We Steal?

- Devote yourself to observing and trying to understand humanity. One of a writer’s primary duties is to reproduce the human experience on the page with as much fidelity as possible.

- Write what you know…within limits. If we followed this advice to the letter, we wouldn’t have any science fiction.

- Introduce “mysteries” into your work to make exposition all the more compelling. Your stories should introduce meaningful dilemmas anyway; use them to make your exposition even more of a treat to the reader.

Short Story

2010, ID, Joyce Carol Oates, Perspective, The New Yorker

What do we notice? Mr. Nemerov employs, in my view, a somewhat loose iambic pentameter in the poem. Unlike a more rigid example (“shall I comPARE thee TO a SUMmer’s DAY?”), the stressed and unstressed syllables are harder to identify. I wonder about the effect of this looser meter; are these lines more “accessible” to those who don’t yet realize they like poetry?

What do we notice? Mr. Nemerov employs, in my view, a somewhat loose iambic pentameter in the poem. Unlike a more rigid example (“shall I comPARE thee TO a SUMmer’s DAY?”), the stressed and unstressed syllables are harder to identify. I wonder about the effect of this looser meter; are these lines more “accessible” to those who don’t yet realize they like poetry?  It bears mentioning that Mr. Nemerov served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the U. S. Army Air Forces during World War II. Perhaps the first thing we notice is now Mr. Nemerov is playing with meter and rhyme. The first two lines of each stanza are cast in that “loose” iambic pentameter and the last two lines of each stanza rhyme.

It bears mentioning that Mr. Nemerov served in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the U. S. Army Air Forces during World War II. Perhaps the first thing we notice is now Mr. Nemerov is playing with meter and rhyme. The first two lines of each stanza are cast in that “loose” iambic pentameter and the last two lines of each stanza rhyme. The first thing we notice is that the poet is adhering more strongly to the meter than was the case in the first two poems. Isn’t that image a beautiful one? Mr. Nemerov reminds us that everything about language is beautiful, including the very pen strokes we use to communicate our thoughts.

The first thing we notice is that the poet is adhering more strongly to the meter than was the case in the first two poems. Isn’t that image a beautiful one? Mr. Nemerov reminds us that everything about language is beautiful, including the very pen strokes we use to communicate our thoughts.