Title of Work and its Form: “” ‘There’s just one little thing: a ring. I don’t mean on the phone.’ “—Eartha Kitt,” poem

Author: Kathy Fagan

Date of Work: 2006

Where the Work Can Be Found: The poem was originally published by the prestigious online magazine Slate. By all means, go check it out right now.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Structure

Discussion:

Kathy Fagan’s “’There’s just one little thing…’” is a poem whose title connects its narrator with that of the song “Santa Baby.” (Ms. Fagan certainly announces that she has taste in her choice of referencing the Eartha Kitt version.) The poem’s narrator clearly announces her (or his…who knows?) desire to receive a diamond ring and to take her rightful place on a pedestal in the relationship. The narrative is complicated in the last two lines:

So snare it,

Santa, from that other

sorry cow.

The Baby Jesus phoned,

says I should wear it now.

It seems as though the narrator has a romantic rival, the “sorry cow.” The reader is left wondering how the conflict will eventually be resolved.

The first thing that jumped out at me was the interesting structure of the poem. Ms. Fagan prepared me to think about popular song, so I couldn’t help but think of the work in that way. The poem begins with a kind of recitative, preparing the reader for the primary “melody” in the verse. The “bridge” arrives as the meter changes completely with the lines “Been bottom./ Done shouldered.” Verse 2 arrives with the 1-2-3 repetition of the lines beginning with “O” and those last two lines serve as a kind of button on the “song.”

It may seem crazy to split up a serious poem in this manner, but Ms. Fagan clearly had some kind of structure in mind. Look at the changes in meter that Ms. Fagan employs:

| Section | Beginning/Ending Lines | Dominant poetic feet |

| “Recitative” | “In lieu…list forthwith” | Anapests – Iambs – Anapests |

| “Verse 1” | “Do not buy…buckle under” | Dactyls |

| “Bridge” | “Been bottom…my skin” | Dactyls/Trochees |

| “Verse 2” | “O halogen…all this time” | Iambs – Primus Paeon/Trochee - Iambs |

| “Button” | “So snare…wear it now” | Iambs |

By mixing it up, Ms. Fagan keeps her audience engaged and prevents readers from being lulled into complacent scanning of the lines. It’s also a lot of fun to transfer between meters, isn’t it? Playing with words and how they fit together isn’t just for kids, right? Adults also enjoy the twists and turns they can find in sentences. Switching between meters also allows Ms. Fagan to place emphasis on certain ideas. There are points in the poem in which the changes stop the reader momentarily. It seems particularly apparent that Ms. Fagan intends “Been bottom./ Done shouldered.” to represent something significant about the character of her narrator.

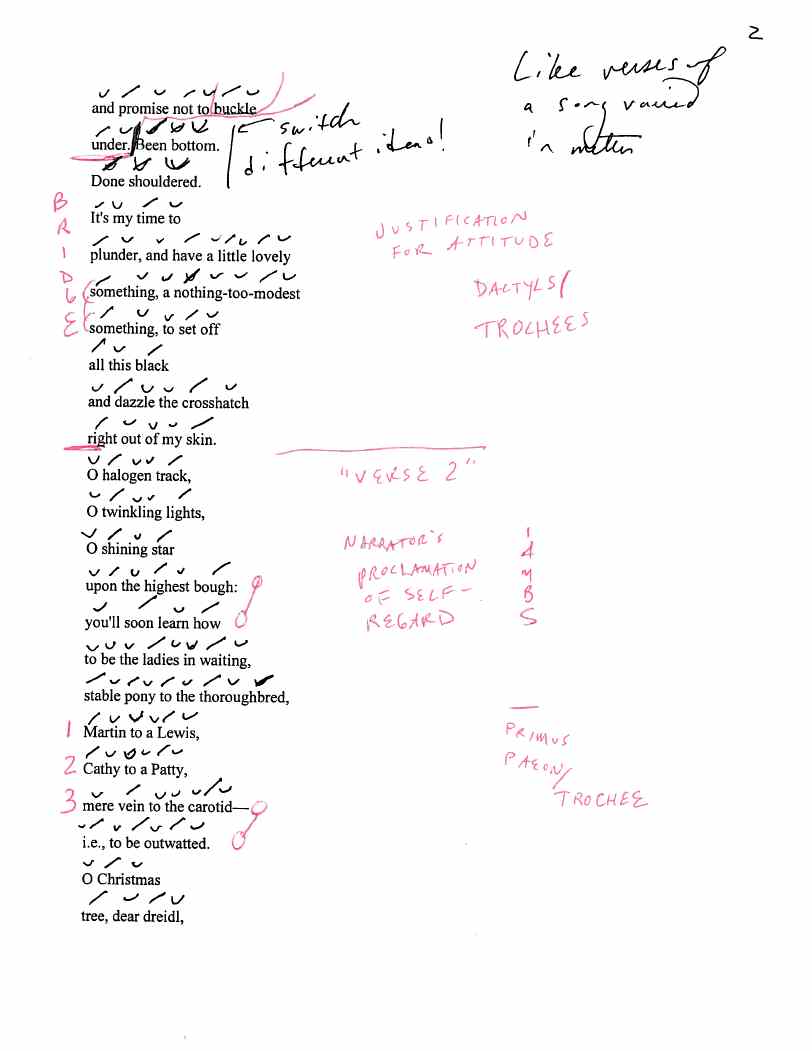

Poetry, of course, is best communicated by the human voice. (If you’ll notice, the link to Ms. Fagan’s poem allows you to hear her reading her work!) When you’re considering the written word on the page, it’s up to you to try and decode the unique kind of music the poet intends to make. Break out your favorite kind of pen and annotate the poem. Jot down the ideas that come to mind! Circle the rhymes you may find! Count the repetitions hidden in the lines! One of the reasons that workshops help so many writers is that everyone in the room is sharing ideas about the work. Some are great, some are just okay, but this analytical process allows everyone to understand the work on a deeper level. When you mark up a page, you’re entering into a discussion with the poet. I hadn’t come up with my overall idea about this poem’s structure until I made my chickenscratches. What might it look like if you mark up a piece of writing? Here’s what I did to a section of Ms. Fagan’s poem:

There’s no right or wrong; I simply wrote what I thought about the piece, which led to even bigger concepts. You’ll also notice that I tried to scan each syllable in the poem, deciding which should be stressed or unstressed. When I compared my thoughts to the way Ms. Fagan made them sound in her reading, I noticed a few differences that illuminated my understanding of the poem. (Her metrical ideas were better, of course.)

There’s no right or wrong; I simply wrote what I thought about the piece, which led to even bigger concepts. You’ll also notice that I tried to scan each syllable in the poem, deciding which should be stressed or unstressed. When I compared my thoughts to the way Ms. Fagan made them sound in her reading, I noticed a few differences that illuminated my understanding of the poem. (Her metrical ideas were better, of course.)

What Should We Steal?

- Place emphasis on important ideas by changing the meter and flow of your sentences. It’s very easy for your reader to be carried away in the wave of words and ideas that you are communicating through your use of beautiful and florid language that tickles their frontal lobe and creates fireworks in their medulla and reinforces why they enjoy reading in the first place. So switch it up sometimes! Use different kinds of sentences for different effects!

- Deface everything that you read to gain a greater understanding of the author’s thoughts and intentions. It’s not always possible to discuss everything you read with other smart people. When you read with a pen in hand, you become your own reading group. (If you’re reading a library book, you should write in pencil.)