Title of Work and its Form: “The Status of Myth,” short story

Author: Owen King and Kelly Braffet (You can follow Mr. King on Twitter @OwenKingwriter and Ms. Braffet at @KellyBraffet.)

Date of Work: 2013

Where the Work Can Be Found: The short story was originally published in five daily chapters by the top-notch online journal Five Chapters. You can read the story for free right here.

Bonuses: Here is Ms. Braffet’s Amazon page and here is Mr. King’s. The two writers happen to be married; here is a Lit Park interview in which they discuss what that is like. (I don’t want to say the interview is adorable…but it’s pretty adorable.) Here is an interesting Salon piece in which Ms. Braffet glorifies the flawed literary character. I’m sure you love NPR as much as I do; here‘s an interview in which Mr. King discusses what it is like to grow up in a literary family.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Serialization

Discussion:

“The Status of Myth” is a collection of five stories that reflect upon the nature of childhood and adolescence. Each section focuses upon a different young person and situation:

- An unnamed young man who was born on the day “the Steelers won the Super Bowl.” He experiences love and loss and creates a life for himself.

- The first-person narrator is a teenager who burns a statue of a monk with his twenty-six-year-old brother.

- A second-person narrator who engages in a discussion with “you” about “the hunters:” young people who seem perfectly ordinary by day, but turn into pleasure seekers at night. (I am reminded of what weekends are like in a college town…)

- A group of schoolchildren reflect upon the disappearance of a peer and Ganymede, a gay pop star visits a Make-A-Wish child

- A young girl is taught a devastating lesson by her father: if you help others, you infantilize them and take away their ability to fend for themselves.

I don’t know if the story was written for Five Chapters, but the story seems perfectly designed to make use of the journal’s conceit. The stories are serialized over five days; readers have the option to consume approximately 2,000 words at a time before waiting for the next installment to go live. If you go this route, you have a whole day and night to think about each bit of the story. What does the Five Chapters serialization do for this particular story? On Day 2, you may wonder about the connection between parts one and two. On Day 3, you probably realize that the sections feature different characters and begin to think about the thematic relationship between each vignette. By Day 5, you are prepared to offer some kind of conclusion as to the meaning of the work as a whole.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of serialization? I’ve addressed this issue before in a paper in my 19th-century English Lit class. (You’d be surprised by the number of similarities between Arrested Development and Bleak House.) In case you’re not my awesome professor-the only person to have read the paper-here are some of my thoughts.

Serialization can really boost the suspense inherent in a work and draw your reader closer. Think about how you feel during the last few weeks of a TV show that you love? A lot of people spent a lot of time talking and thinking about everything that happened toward the ends of Breaking Bad and LOST. When you blow through the episodes in a Netflix marathon, you don’t give yourself a chance to stop and to reflect and to absorb the subtext and to find connections between later plot developments and symbols and earlier ones. My experience with “The Status of Myth” is certainly representative of this phenomenon. After I selected the story, I read the piece straight through. Did I enjoy it? Sure. But I may have enjoyed it more if I read the story in a more leisurely fashion. (And in the fashion specific to Five Chapters.)

Mr. King and Ms. Braffet do something cool in Part Four. After introducing Ganymede and establishing that he is meeting a Make-A-Wish child, the authors describe some of the visit. Hannah, “the cancer girl,” is clearly ill. She has “a few wisps of orange hair on her freckled scalp, tubes in her nose, and an IV stuck in the back of one hand.” Hannah’s bare skin feels like construction paper.

What’s the usual ethos, the usual feeling that people have for sick people…and sick children in particular? We’re InstaSad™. We often turn these kinds of people into “heroes” and “brave victims.” In doing so, we remove some of their humanity, right? Sure, Hannah is ill and that’s VERY sad. However, Hannah is still alive and is a real live young lady with the same characteristics we all share. I love that Mr. King and Ms. Braffet make Hannah into a human being instead of using her as a kind of prop.

What a sweet little scene:

“This must really suck for you,” said Hannah. “You must have to meet so many dying kids. You must have to meet so many that you probably barely have a minute for yourself. I bet you’ve met, like, a cemetery worth of dead kids by now.”

G laughed. He hadn’t expected that. “I like you, Hannah Dewhurst. You’re funny.”

“Let me have some of your coffee,” she said.

“Should you?” he asked.

“No.”

“Okay.”

He slid the mug over, peeked around the edge of the frosted glass partition to make sure the coast was clear, and told her, “You’re good.” Hannah took a sip and slid the mug back.

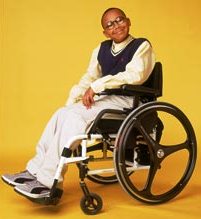

Hannah’s not allowed to have coffee because she’s very, very ill. As a child, she wants what she can’t have and is attracted to “coffee,” that adult drink. Totally normal. Ganymede weighs the pros and cons of sneaking her some caffeine and lets her break the rules. Totally normal. Even better is Hannah’s self-understanding. She’s a dying kid and knows it. She knows that Make-A-Wish trips are not exactly Ganymede’s favorite pastime. What’s the big lesson? Characters shouldn’t be used as props, particularly when their only purpose is the exploitation of a disability. Hannah is a young lady who just happens to have cancer. Walter “Flynn” White Jr. has cerebral palsy, but the condition doesn’t define him. Remember Stevie? Malcolm’s disabled friend from Malcolm in the Middle?

Sure, practicality and logic forced the plots on the show to sometimes account for Stevie’s disability, but the children treated him just like everyone else. Your characters may have big problems to overcome, but your work will mean more when you avoid casting them as untouchable angels, but as real humans.

What Should We Steal?

- Construct your work in a manner appropriate to the form in which it will appear. If you know your piece is going to appear in serial form, you should probably take another look at the work to ensure the sections will flow and will work as a whole. If you’re appearing on Good Morning America, you should probably understand that Robin Roberts will ask you about your recent assault charge and get in front of the situation as best you can instead of blaming the situation on “h8rs” and throwing a chair out a window when you get back to your dressing room.

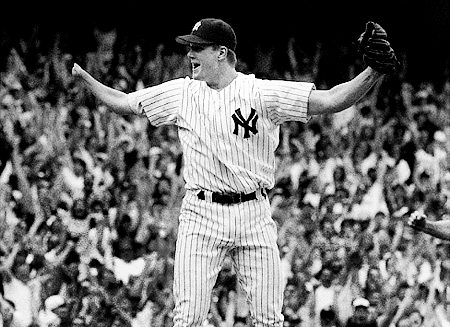

- Avoid turning your super sympathetic characters into statues perched on towering pedestals. Jim Abbott doesn’t want your sympathy, nor does he deserve it. Mr. Abbott is interesting because was a top-notch major league pitcher for quite some time, pitched a no-hitter for the Yankees and seems to have a great life. (Oh, and he was born without a right hand. No biggie.)