Hey, Why’d You Do That, Christopher Citro?

Writers are asked many general questions about their craft.

…”What is your overarching philosophy regarding the inherent power of fiction?”…”What IS-character-to you?”…”What is the position of place in your work?”…

These are great and important questions, but I’m really curious about the little things. In the “Hey, Why’d You Do That” series, I ask accomplished writers about some of the very small choices they made during the process of composition.

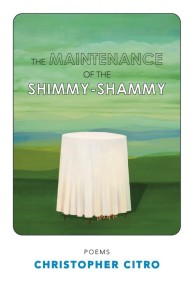

Christopher Citro is one of those writers whose names seem so familiar because you keep seeing it in all of your favorite lit mags. His work has appeared in a ton of places, including The Journal, Ploughshares, Redivider and a number of other journals you wish would accept your own work. His first book of poetry, The Maintenance of the Shimmy-Shammy, was published by Steel Toe Books. Why not order a copy directly from the publisher? You can also find the book at Barnes & Noble and Amazon.

Yes, you may wish to read 10,000 words in which Mr. Citro elucidates his overall philosophy of poetry. Instead, I am curious about the tiny choices that Mr. Citro wrestles with every time he sits down to put pen to paper. I read and enjoyed “Nerve Endings Like Strawberry Runners,” a poem that Mr. Citro placed in Witness. Why not follow along with the poem and reflect upon the nitty-gritty of his writing process in order to improve your own work?

1) I like poems that have meter because you can read them like songs. The meter also helps you know which words are important. “Nerve Endings…” doesn’t seem to have a consistent meter like in a sonnet, but the first line makes it sound a little like music.

Here it is the way you wrote it: “I’m pure and perfectly formed in this clean shirt.”

Where do you want the stresses on the words and why?

“I’m PURE and PERfectly FORMED in THIS clean SHIRT.”

or

“I’m PURE and PERfectly FORMED in this CLEAN shirt.”

Or did you have another idea?

It’s a treat to respond to a close reading of one of my poems! My own reading of the opening line is basically your second version, except that I’d include a stress on “shirt” as well. For me this has the most natural spoken quality. Others may differ, and that’s perfectly fine, too.

It’s true that this free verse poem doesn’t have a consistent, predetermined meter in the sense of a sonnet. In this poem I was working with a basic five beat/stress line (e.g. lines 1-4, 6, and 7). Four beat lines pop up for rhythmic variation and emphasis (e.g. lines 5, 8 and 10). Then in the last three lines, the beats overflow this container when the current of the narrator’s imagination overflows the animal “vessels” it’s pouring into.

2) The endings of lines two and three seem pretty awkward. Line two breaks in a weird place in the sentence and line four begins with a pretty weak word. You must’ve done this on purpose. Were you trying to mark a transition in the poem or something?

I liked ending line two on “convinced” before going on to relay what the speaker is not convinced of, to allow the reader to entertain other possibilities.

Line three is end-stopped with a comma at the conclusion of a phrase, so to me it doesn’t feel all that rhythmically or syntactically awkward. Line four does begin with an adverb and an unexpected qualification of the thought in the previous line. That moment of statement + qualification signals a certain movement (certainty + uncertainty) that reflects some of the way the narrative logic of the poem plays out (i.e. this then that…or possibly not that).

3) Oh…..I get it. The “I” character is imagining what they might do if they were a dog. The poem’s obviously pretty and all. And people like dogs, so they should like poems about dogs. How do you make a poem fancy without confusing people? Who do you imagine reads your poem?

I almost left this poem in my abandoned folder because I was worried it would come across as too “fancy” or “pretty.” I am generally suspicious of that kind of thing for many reasons including not wanting to give the impression that my poem is in any way a puzzle to be solved. I guess I stayed with this poem because to me it’s more than just “getting” this central metaphor. As for possibly confusing people, I’m usually not super worried about that. Life is confusing, so why shouldn’t at least some poems be? Plus, it can be fun to experience confusion in the safe environment of a poem. Plus, confusion can be one way of allowing a poem to have a heart of mystery. Plus, I sure don’t create poems out of moments of certainty.

As to whom do I imagine reads my poem? People. Readers. That may come off as glib, but I honestly can’t think of any other answer. I don’t write for any specific audience in mind. If cats could read, I’d try writing for them, but it would look a lot different I imagine. Pictures of mice in a row with a shrimp at the end, punctuated by pillows in sunbeams. Ok, now I want to write a poem for a cat.

4) Look at the last line and an eighth:

“…I’ll

let go, watch the bird reach out my other hand to the sky.”

The bird can’t “reach out” the narrator’s hand…that’s something narrators do themselves! Why’d you have the other “character” in the poem do that specific movement?

I’m suspicious of the usefulness of any approach towards reading a poem that applies too stringently any external logic or understanding of the way the world supposedly works. In a workshop long ago I remember watching a conversation about a poem completely derail when people would not stop arguing whether or not a locomotive train could whimper. In the poem there was a train that whimpered and some people were maintaining that it could whine, perhaps, but not whimper. I started whimpering in my head after about ten minutes of this sort of thing.

In my understanding of the poem, the speaker’s consciousness, in the brief moment of seeing his/her hand as an object in the world separate from the self (as a thing that’s aging, that looks like an older person’s hand), experiences that un-moored sense of self floating free into other animal objects in the local environment. It’s a dog for most of the poem and then, after a moment of empathy, a bird. One of the speaker’s hands is the dog, the other is the bird. In your terms, the narrator is in the bird at the end as he/she has been in the dog up to then. The speaker is both predator and prey, earth-bound and sky-flier, so on and so forth.

Speaking too much like this gives me the feeling that I’m reducing my poem to an idea though, and that makes me uncomfortable. Because it’s not an idea. It’s a contraption made out of words.

5) This poem has an epigraph: that little quote at the beginning. Writers like prompts. Did you get that on the “writing prompts” subreddit? Was it under the cap of your Snapple bottle? Tell me how that whole thing worked so I can publish a poem in Witness, too.

Many years ago I went through an epigraph-happy phase where I stuck them on almost all my poems. I just love the opportunity to allow voices other than my boring old voice into my poems. I calmed down eventually. I know not this “writing prompts” subreddit of which you speak. And my iced tea choice is limited to unsweetened Lipton whose marketing style doesn’t run to quotes under the cap.

I handwrite all my poems in a series of journals interspersed with diary entries, dreams, to-do lists and quotations from poems and novels I’m reading. Most of my current poems with epigraphs have had them added after the initial draft. Not because I went searching, but because in typing up the poem I saw that I’d copied out a quote shortly before or after writing the draft which plays off interestingly with the poem.

As for how to get a poem published in Witness, I’m still happily amazed that it happened to me and haven’t any advice other than the usual thing about the crossroads, midnight, and hooking up with a geezer with a pointy red tail. Worked for me!

Christopher Citro is the author of The Maintenance of the Shimmy-Shammy (Steel Toe Books, 2015). He won the 2015 Poetry Competition at Columbia Journal, and his recent and upcoming publications include poetry in Prairie Schooner, Ploughshares, Best New Poets 2014, and The Greensboro Review, and creative nonfiction in Boulevard and Colorado Review. He received his MFA from Indiana University and lives in Syracuse, NY.

Leave a Reply