Title of Work and its Form: “Bottled Spirits,” creative nonfiction

Author: Jason Tucker

Date of Work: 2011

Where the Work Can Be Found: The piece first appeared in Fall 2011’s Issue 8 of Waccamaw, a cool online journal. You can read it here.

Bonuses: Here is an essay Mr. Tucker published in The Common. Here is a bit of flash nonfiction Mr. Tucker placed in Prime Number. Mr. Tucker happens to be married to an equally talented writer: Amy Monticello.

Element of Craft We’re Stealing: Narrative Perspective

Discussion:

Through the course of eight sections, Mr. Tucker sheds light on the Alabama of his childhood: a constantly evolving place that represents the best and worst that can happen when many different people come together to forge a culture. The title refers to “bottle trees,” a tradition rooted in African folklore. These bottles hanging from trees were intended to capture and hold evil spirits. Today, many people consider bottle trees to be just another African import, “like okra and the banjo.” After using the trees as an entry point, Mr. Tucker tells lush stories about the relationship between his family and the land and the culture that developed as a result of the diverse influences different kinds of people had on the South. We can taste the delicious chestnuts that come from his father’s chestnut trees. We marvel at the contradictions of the New South; it’s a place where you can find “Emma the Voodoo Lady” alongside the majority, who don’t resemble “Old South caricatures.” The meaning of spirituality is also an important thread in the piece. The South responsible for Mr. Tucker’s development is a place in which so many parts of life-history, food, drink, music-become a part of of the area’s lore and a potent kind of mythology. Mr. Tucker ends the piece by recounting a scene in which his father took him around an outdoor flea market. Father enjoyed showing son all kinds of antique tools, some of which he could use in the workshop and some of which he enjoyed because of the bygone time they represent. Tools, the work of callused hands, are like a bottle tree in a way. Both objects are highly personal and are “things in which each generation could trap the world as they understood it, no matter how the rest of it kept changing.”

One reason I love essays such as this is because Mr. Tucker immerses me in a world that I don’t really understand very well. I’m a Yankee, through and through. Sure, I’ve seen Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil and I’ve read The Firm and I saw that Tales from the Crypt that was about voodoo, but I don’t think it’s fair to judge the South by those benchmarks. This essay does a great job of condensing a number of complicated concepts into a very small number of pages. Let’s break down the structure of the sections Mr. Tucker included in the essay:

- “The idea that you could bottle a spirit…” Introduction of the bottle tree and the point of the essay: Mr. Tucker will be discussing the “Alabama of his childhood” and how times and ideas change.

- “Daddy keeps things…” Introduction of the father and his facility building things and hunting and so on. Is “Daddy” a stereotypical “Bubba” guy? Of course not. He “nurtures” a pair of American chestnut trees and sends his loving son a box of their otherwise unavailable bounty.

- “I’ve only ever seen…” Back to the bottle trees. Mr. Tucker layers in some of the “old South/new South” conflict. The lasting effects of slavery are still present, but “Perry County has black lawyers and bankers and politicians,” too. Emma the Voodoo Lady is a bit of a throwback. One of Mr. Tucker’s acquaintances throws an aluminum can in her vicinity: a slight sign of disrespect.

- “Way out in the Black Belt prairie…” Beautiful description of nature juxtaposed with the image of the occasional anti-gay church sign you might see here or there.

- “Daddy never went to church…” Ties general spirituality of region to Mr. Tucker’s experience. Daddy believes very deeply in guns and “no trespassing” signs. Guns as family legacy and way to ward off evil. (Whoa, hey, I’m smart because I noticed that Mr. Tucker mentions “the Misfit,” the antagonist from Flannery O’Connor’s story, “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” Just another advantage to being fairly well-read!)

- “Now, the bottle tree…” Very brief section. Mr. Tucker considers the purpose of mythology and what a talisman means to its owner.

- “It took us two hours…” Back into narrative. Mr. Tucker goes to the Bottletree Cafe. There are cool tunes and great food, but the bigger point Mr. Tucker wants to make is that time and youth seem to want to decontextualize objects like the bottle tree. “to render objects powerless with a jolly application of hot glue and shiny things.”

- “Daddy didn’t like to leave the house much…” A description of the family trip to Trade Days at Tannehill State Park. The themes are united (of course); Mr. Tucker describes what was passed town to him from his father and does so through the lenses of nature and the creation of meaningful objects and how people can themselves become artifacts.

So what do I like about the structure? Mr. Tucker makes the essay meaningful on both the micro and macro levels. Yes, the piece is about his experience and his understanding of the region that shaped him. But he’s also able to step back and have some objectivity. I’m guessing Mr. Tucker frowns deeply upon the buddy who threw the can in Emma’s direction, but no one learns anything if he spends two pages badmouthing the guy. This kind of creative nonfiction essay requires the writer to be a journalist and participant at the same time.

I am reminded of Jeremy Collins’s cool Chautauqua piece, “When We Were Young and Confederate.” Both pieces paint the shapes of the ghosts of the South that still exist. While Mr. Collins is a lot more “emotional” in his piece, he is similarly objective. When he confesses the unpleasantness of his youth, he reports faithfully…even though it makes him look a little crummy. We’re all on a tightrope when we compose CNF; I suppose we need to decide the distance that should separate our feet from the ground.

I also love the rhythm of Mr. Tucker’s paragraphs. Now, he’s clearly great at description, but he seems to know that we’d tire easily if each sentence is equally complicated and detailed. Look at what the author did with this paragraph in section III:

|

Sentence |

Analysis |

| I’ve only ever seen a couple of bottle trees made by regular people—you know, people who aren’t trying to look like folk artists. | Medium-sized sentence; description and a joke split by an em-dash. |

| The one I saw most often belonged to a woman we kids called “Emma the Voodoo Lady.” | Short sentence. Description. |

| With her sack and her stick, Emma’d hunch along the side of the road, picking up cans. | Short sentence. Description. |

| She lived in a rotting white clapboard house in Folsom—the remnants of a plantation handed down through the Webb family ever since the government first granted the land in hopes of populating this wild territory. | Long sentence, delineation of history. |

| I don’t know for sure if Emma descended from local slave families, but for poor black people in Perry County, that’s a safe assumption. | Medium sentence. Author’s conjecture |

| Whoever her people were, the government didn’t give them plantation-sized tracts of land. | Short sentence. History. |

| Her bottle tree might not have looked like slavery to me, but now when I imagine Emma walking the ditches in the hot mist of an early summer morning, she looks like she’s carrying a bag of our sad and shameful history. | Long sentence. Meaningful statement that makes use of the thoughts in the previous sentences. |

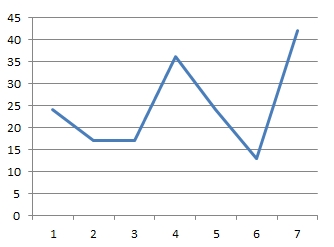

Now look at the shape of the paragraph if you chart how many words appear in each sentence:

What’s the point of all of this? Mr. Tucker is demonstrating writerly restraint. Life proceeds according to a number of rhythms: changes of season, familiarity followed by contempt, and so on. Mr. Tucker allows himself to include some long and beautiful sentences, but makes sure that he doesn’t tire us out and that the bare description of setting and character are crystal clear.

What’s the point of all of this? Mr. Tucker is demonstrating writerly restraint. Life proceeds according to a number of rhythms: changes of season, familiarity followed by contempt, and so on. Mr. Tucker allows himself to include some long and beautiful sentences, but makes sure that he doesn’t tire us out and that the bare description of setting and character are crystal clear.

What Should We Steal?

- Understand your role in the story…even if it’s about your life. Objectivity may serve you well in creative nonfiction, even if it seems strange to detach yourself from events that took place in your own life.

- Ensure that your paragraphs have rhythm. You’ll wear your reader out if your sentences are wall-to-wall pedal-to-the-metal. Think of each paragraph as a medley; you need to mix together some uptempo scorchers and some slow love songs. Adagio and presto.